Tax devolution is welcome – but the system increasingly lacks coherence

There is a strong case for a review of how devolved and local government is funded.

April 2018 marks the latest step in the process of tax devolution. Akash Paun argues that these are important reforms, but the system is increasingly complex, making the case for a full review of how devolved and local government is funded.

There has been a striking imbalance in the powers of the institutions in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast since devolution began in 1999.

The Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland governments manage around 70%, 60% and 90% of identifiable public expenditure within their respective territories (including local government spending). However, until recently they directly controlled just 5% of tax revenue (business rates), plus having indirect control of council tax (domestic rates in Northern Ireland), representing a further 5% or so of the tax take.

England is still more centralised: local government oversees about 30% of public spending, but much of this is ring-fenced for specific purposes. The only local tax is council tax – and even here there is substantial national control.

These arrangements have been frequently criticised for creating weak fiscal accountability and keeping devolved and local government dependent on the centre.

But this is now changing, and this week marks the latest step in an ongoing process of tax devolution, designed to close the gap between expenditure and revenue-raising powers. This is an important objective, but one that the Government is approaching via a series of separate reforms instead of considering the logic of the system as a whole. It is time for a full review.

The latest step in the process of tax devolution

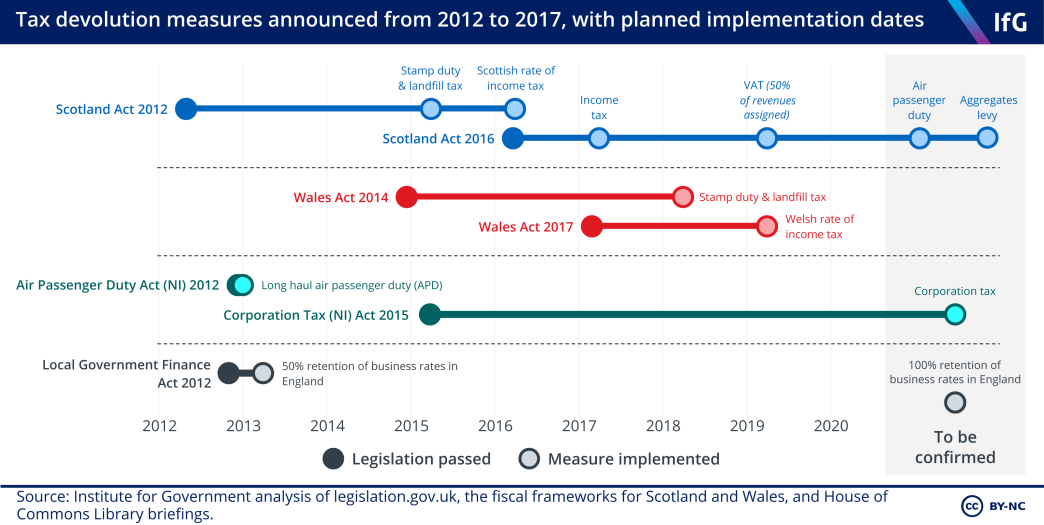

This week, stamp duty and landfill tax become the responsibility of the Welsh Government for the first time. In addition, Scotland has just introduced a new set of income tax brackets, using powers devolved a year ago to replace the existing three tax bands with five.

Scotland already has control of landfill tax and stamp duty, which it replaced with a more progressive Land and Buildings Transaction Tax in 2015. Northern Ireland gained control of long-haul air passenger duty (APD) in 2012, setting the rate at 0% to fend off competition from Irish airports.

The process is far from finished. Under legislation already passed, half of VAT revenue collected in Scotland will be assigned to the devolved budget from next year. VAT will remain a national system, but the Scottish budget will rise and fall in line with VAT receipts. APD was due to be devolved this year, but the transfer has been delayed due to concerns that the Scottish Government plans might fall foul of EU state aid rules. Aggregates levy (a tax on the extraction of rocks) will also be devolved in future.

From April 2019, Wales will gain partial control over income tax, enabling it to set tax rates, but not to change the banding system as Scotland has just done.

Once all these changes are implemented, the Scottish Government will control an estimated 43% of Scottish tax revenue. In Wales the figure will reach 21%. These reforms therefore go some way to closing the gap between devolved expenditure and revenue-raising powers.

Reform is incomplete and governed by contradictory motivations

These are important reforms, but what is striking is how changes in each of the four UK nations reflect very different – even contradictory – rationales.

In Scotland, it was the political pressure of the 2014 independence referendum that persuaded the reluctant Conservative and Labour parties to agree an extensive package of devolved fiscal powers. At the same time, the Government committed to retain the Barnett Formula, which provides for continued high public spending in Scotland. Public spending is about 20% higher in Scotland than England.

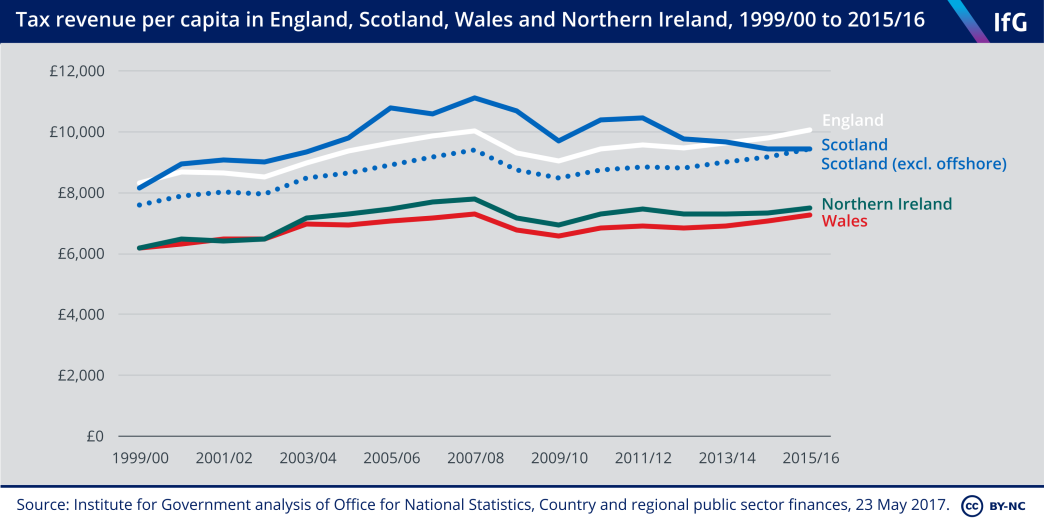

In Wales, there was less support for tax devolution, amid concerns about the impact on the Welsh budget. Institute for Government analysis shows that tax revenue per capita is about 30% lower in Wales than England, so fiscal autonomy is a risk as well as an opportunity. Wales is also underfunded compared to Scotland, despite being poorer. The UK Government therefore committed to a new ‘fair funding’ formula for Wales that guarantees the Welsh budget will remain at least 15% above English spending on equivalent policy areas.

In Northern Ireland, the big change agreed in 2015 was to devolve corporation tax, but this has been postponed following the collapse of power-sharing in Belfast. Here, as with the earlier transfer of long-haul APD, the idea was to enable the North to compete with the low-tax Republic of Ireland for business investment. Corporation tax devolution has been ruled out within Great Britain precisely to avoid this kind of tax competition.

As for England, the Government is committed to business rate localisation, meaning local government will retain 100% of business rates revenue. The objective is to strengthen incentives for councils to support business growth. But revenue varies enormously across England, so any new system must retain substantial redistribution from richer to poorer areas. The details have yet to be worked out, and this reform is being introduced slowly via pilot projects. Other proposals for tax devolution within England (for instance to London) have been rejected. Overall, England remains highly centralised.

There is a strong case for a review of how devolved and local government is funded

The overall impression is of a semi-reformed system that lacks a clear vision for how subnational government should be funded. There is no direct link between spending levels and economic need, and devolution of tax powers has proceeded as a series of ad hoc fixes to discrete problems. The old centralised approach was at least relatively simple. We are now moving towards complexity without coherence.

There is a strong case for a full review, looking at which fiscal powers should be held at which level of government, how tax revenues should be pooled and shared, how economic need should be taken into account, and how to replace EU funding for agriculture and regional development. Brexit may also offer new opportunities for tax devolution, since EU regulations currently constrain the ability to vary taxes such as VAT, alcohol duties and (as noted) APD within the UK.

However, the Government will fear the consequences of opening up a Pandora’s box. Far easier to leave things alone until it becomes politically or fiscally unsustainable to do so, and then to make as few changes as possible. Expect more incremental reform and tinkering.

- Topic

- Devolution Public finances

- Keywords

- Tax Local government

- United Kingdom

- Scotland Wales Northern Ireland

- Devolved administration

- Welsh government Scottish government Northern Ireland executive

- Publisher

- Institute for Government