Today’s Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Constabulary (HMIC) report highlights cracks emerging in policing. But the police service has held up much better than others. Tom Gash asks: will it continue to do so, or are we mortgaging our safety?

Some of today’s newspaper headlines suggested that the police were in “meltdown”, following the publication of Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Constabulary (HMIC) annual report on police effectiveness, which examines the 43 forces in England and Wales. In interviews, Her Majesty’s Inspector of Constabulary Zoe Billingham warned against saying this was a full-blown crisis but highlighted that HMIC’s report was far more critical than in previous years. HMIC was raising a “red flag”, she said, warning that there is “rationing of policing… by stealth”.

Headlines vs data

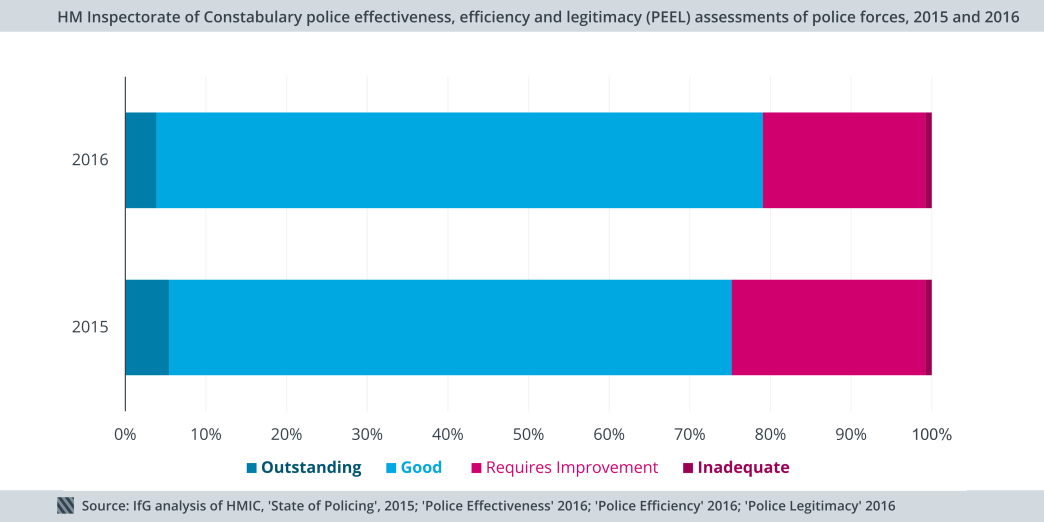

The overall tone of the media debate today does not quite fit the data. The Institute for Government’s Spring 2017 public services Performance Tracker, published this week, shows that police performance has, in fact, held up remarkably well since 2009/10. Despite real-terms funding cuts of 14% and reductions in officer numbers of 16% from 2009/10 to 2015/16, inspectorate reports showed fluctuations in the performance of different forces but no downward trajectory overall. The chart below shows that in fact more forces improved than got worse last year. Policing has somehow managed to maintain performance – at least by the HMIC’s own assessment.

This story of relative resilience is in stark contrast to other service areas, such as the prison service. Here, the Institute’s Performance Tracker shows suicides and violence in prisons rose from 2009 to 2016 – and the Treasury has been forced to inject emergency funding.

Though the data is far from clear, there are some reasons to suspect that strains in policing might be increasing, even if they have not yet translated into performance drops. Performance Tracker shows more staff on long-term sickness leave, a sign of strain that is reflected in stories highlighted by the BBC and others about detectives being swamped by workload. In Performance Tracker we urged government to find more ‘leading indicators’ of strain, so that the tricky spending decisions of the future are even better informed.

Rationing and prioritisation

The HMIC report draws on detailed data that is (unfortunately) not publicly accessible, in order to draw more detailed conclusions about police performance. Drawing on this data, HMIC point to many areas where police must do better: from community policing to dealing with domestic violence to tackling organised crime. There is a strong tone that ‘rationing’ police response to crime is unacceptable. But we are not given clear data on whether rationing is increasing – a deficit we should hope is addressed in future reports. It’s also not entirely clear whether it’s fair to expect police not to prioritise certain crime types and activities in the circumstances.

The police do appear to have been prioritising the urgent at the expense of the important. In response to cuts, police have protected response and investigation work by cutting the numbers involved in crime prevention. In the words of HMIC:

“The analytical capacity of many forces has reduced, meaning that their ability to process intelligence and continually to improve their approaches to crime prevention has also reduced”.

In my book on crime Criminal: The Truth About Why People Do Bad Things, I examined the big shifts in crime across the developed world in the past twenty years. The significant reduction in crime since 1990 (which is now coming to an end) has many causes but, I argued, the main one is an array of innovations that have made it harder to commit crimes: for example, the improvements in vehicle security that have seen UK car crime fall to a sixth of 1990 levels, or the regulation of the scrap metal industry which has made it much harder for thieves to dispose of their goods.

These efforts all involved and were supported by the police, but the approach deployed was focused on solving the precise crime problem at hand. By examining the details of specific crimes – when, where, how, and why they happen – police were able to work with businesses, communities and government agencies to nip crime in the bud. It seems clear that if this is the type of activity we are now stopping as a result of cuts, we should be extremely worried.

Coping with less

The way out of this bind is to pursue at least two of the following three options: more money, tough choices, or ‘transformation’.

More money is frankly unlikely given strains in areas of even greater public concern, such as health and education, and limited government and public appetite for tax increases.

Rationing may be a dirty word but it could also be called prioritisation and it’s an inevitable response to vast unmet demands, in policing as in almost every public service. During recent decades the police role has arguably expanded. Even as crimes such as burglary, vehicle theft and murder have fallen dramatically, the police workload has been maintained by ever-more-thorough investigation of previously too-often-ignored domestic violence and sexual offences, and latterly by online crime. The police are also dealing with a vast array of community problems, from mental health issues to supporting vulnerable citizens with daily problems that are not technically crime.

In the absence of more money, HMIC and others clearly have a duty not just to say what the police must do more of but where they can do less. Setting out ‘red lines’ about unacceptable rationing would help. But we also have to ask hard questions about where services could be changed without undermining public confidence. Could the police ask victims of car crime whether they want an officer to visit their homes, rather than doing a (quicker) phone or videoconferencing call, or spending time exploiting the remote surveillance that tracks car movements in many cities, for example?

Making investigative processes more efficient is an urgent priority to free up time for more serious cases, and for the transformative prevention work that police forces ignore at their peril. On the television show The Big Life Fix, an engineer from the Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science found a way of preventing sheep rustling by inventing an inexpensive pill containing a tracking device that attaches to a sheep’s stomach lining when swallowed. The meat industry says it’s not yet financially viable – but it could be soon.

For every problem, there are inventive solutions that we will only find through interdisciplinary experimentation efforts, and we will only implement effectively with more fundamental changes to police ways of working. Transformation in other areas of service will take time, but the Institute’s work on digital transformation points to the possibilities. And transformation is certainly needed if the police are to adapt to challenges such as cyber-crime.

It is a great thing that the HMIC has cast light on how police forces are adapting – or in a few cases failing to adapt – to austerity. We should be careful not to imply police performance has measurably declined. And we must have a much more honest conversation about what police forces will have to do to manage in a more resource-constrained world.

- Topic

- Public services