Government has increasingly made use of ‘joint ministers’ who work across several briefs or departments. Based on interviews with joint ministers who took part in our Ministers Reflect project, Nicola Hughes and Emily Andrews examine the pros and cons of these roles.

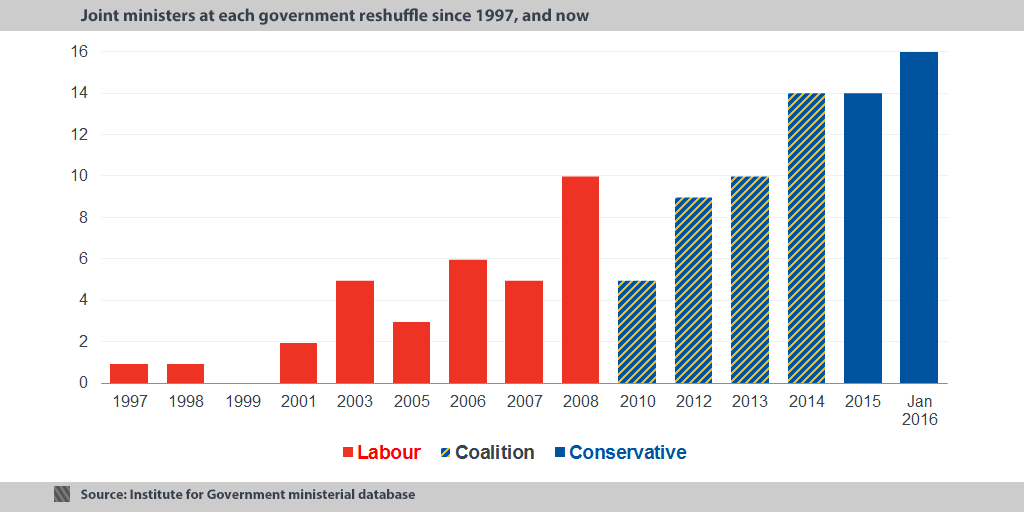

Joint ministers – ministers who are formally ‘shared’ between different departments or hold multiple positions – were an innovation of the New Labour years. There were five such ministers at the start of the Coalition Government in 2010 and the number has increased at every reshuffle since, now standing at 16.

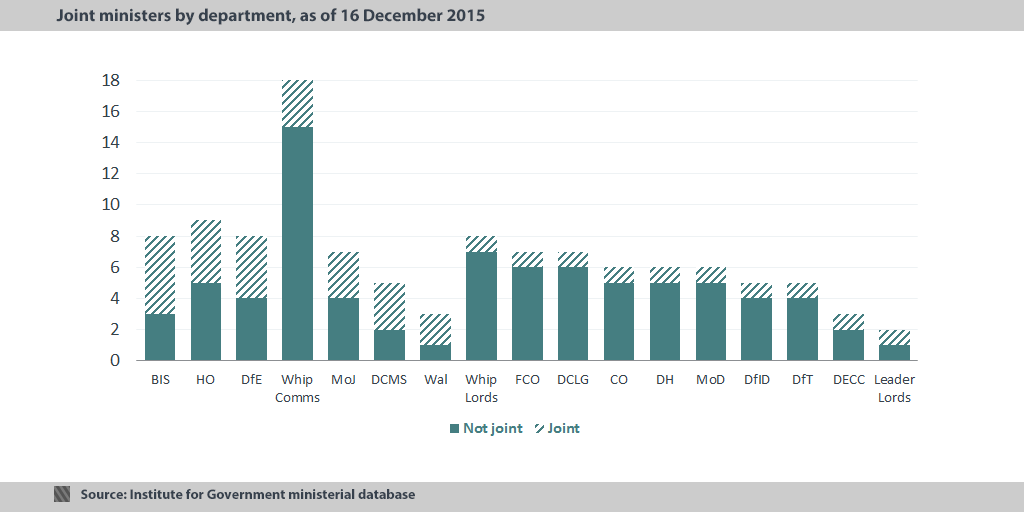

As the chart below (which shows all Whitehall departments that have one or more joint ministers), nearly all departments now have at least one joint minister:

These figures include different types of roles. In some cases joint ministers hold multiple, distinct briefs. Education Secretary Nicky Morgan, for example, is also Minister for Women and Equalities – a brief that is (rightly or wrongly) not usually considered to be a full-time job. In other cases ministers have one brief but are shared across different departments: for example Richard Harrington, who is responsible for resettlement of Syrian refugees and reports to DCLG, the Home Office and DfID.

Given the increase in the number of joint ministers, it is worth pausing to ask how well these roles actually work. Our Ministers Reflect archive provides some insights.

“Preventing the silo mentality”

Joint ministers ought to foster coherence and collaboration across government. Damian Green served as Policing and Criminal Justice Minister, split between the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice. He spoke of the “insights and satisfactions” in “actually trying to make the whole process from… arrest to sentence and beyond rehabilitation or whatever, one process”.

Jo Swinson was more generally “quite a fan of having double-hatted ministers”, reflecting on her time at BIS, where nearly all of the team were shared with other departments. This, she argued, “worked quite well in preventing the silo mentality” and “different linkages being made” across government. Another former BIS minister, Mark Prisk – though not himself a joint minister – was less convinced: “Some of the departments still have a silo mentality. I’m not wholly sure that having ministers across two departments actually changes that. I think that’s superficial, what it means is no one is quite sure whether the person is in their department or the other department.”

“An office in both places”

Working across two departments has obvious practical implications, such as additional demands on the diary: “…visits and speaking at slightly dull conferences and so on, there’s just twice as much of that”, said Damian Green.

There are also two departments to get to know and establish good working relationships in: cultures and practices can vary a lot across Whitehall. Lord Stephen Green, formerly trade minister split between BIS and the Foreign Office, found tactics to get to know both of his departments: “I actually had an office in both places and was punctilious about spending half the week in one, and half the week in the other.”

Green’s successor Lord Livingston split his time similarly and his Private Office “physically moved from one to the other” department. He continued, “…the two departments certainly worked very differently, with very different but both very approachable secretaries of state. The Foreign Office… was very hierarchical and very much in the old traditional style where virtually every decision ended up on the desk of the Foreign Secretary… On the other hand, In BIS, there was more power delegated to the individual ministers”.

“Flatly contradictory advice”

Perhaps the trickiest part of being a joint minister that Damian Green highlighted was “trying to work to two bosses who may well have two different agendas”. He gave one stark example: “you would occasionally get flatly contradictory advice; the two departments would just be advising people in two different ways or there were moments – surreal moments – in August particularly when you’re a duty minister, there was one point where I was required to write to myself as one minister in a department to another, demanding that something happen, which I was tempted to do just to see how the system would cope with this!”.

Although a limited sample, these interviews suggest that the benefits of being a joint minister need to be carefully weighed up against some of the practical difficulties. Certainly they cannot in isolation achieve the elusive goal of ‘joined-up government’. As we’ve argued previously, in areas where cross-departmental collaboration is important the prime minister needs to combine joint ministers who have sufficient authority and status with shared goals, pooled budgets and joint teams. Before appointing more joint ministers, government should be clear on the purpose of their roles and how to support them in navigating competing demands and advice.

Abbreviations for government departments can be found here.

- Topic

- Ministers