Michael Gove’s proposal of a new environment watchdog after Brexit will allay some fears but he needs to be clear about its remit if it is going to fill the 'governance gap', argues Jill Rutter.

The Environment Secretary Michael Gove has set out ambitious plans to establish a new environmental watchdog after the UK leaves the EU. He is right that leaving the EU will leave a 'governance gap' on the environment.

Since being a member of the Single Market, the UK has been subject to EU environmental standards. The EU was credited with forcing a reluctant UK to shed its “dirty man of Europe” habits – and many of the most ardent Brexiteers have made it clear that rolling back on the advances in environmental quality is not part of the Brexit project.

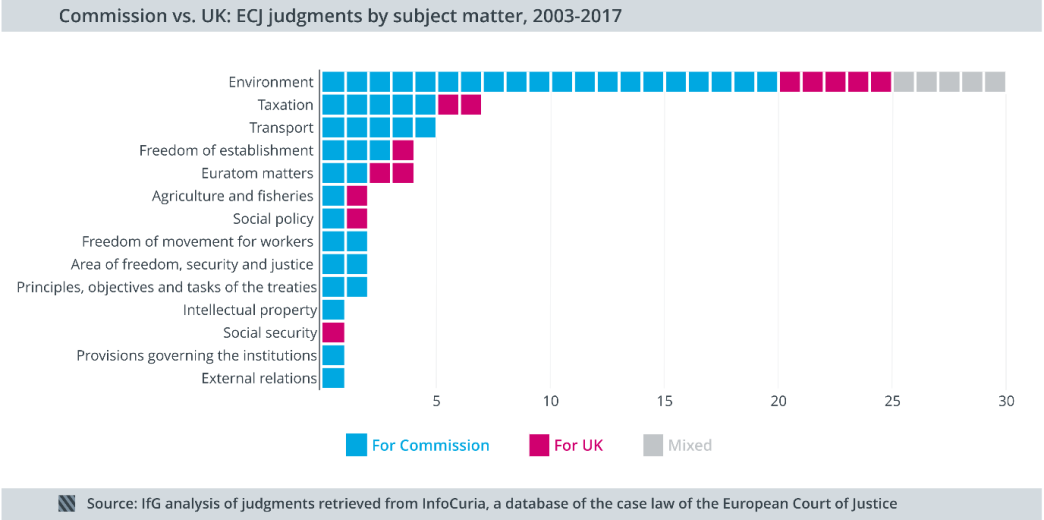

But those who argue that the UK needs the pressure of being challenged by the European Commission to meet its environmental commitments have a point. Our analysis of European Court of Justice (ECJ) judgments from the last 15 years shows that almost half of the cases the Commission brings against the UK relate to the environment and that the UK loses most of them.

Avoiding policy instability is a sensible objective – and might help reassure the EU

Many environmental improvements require long-term investment. The environment has been relatively immune to the sort of policy churn seen in areas which lack an external framework. So it makes sense to entrench agreed long-term objectives, to give business, land managers and other agencies clarity on what commitments they will need to meet.

A genuine independent overseer of environmental performance might also allay EU fears that the UK will undercut its environmental standards.

But we did not have to wait for Brexit to create a new watchdog or introduce higher standards

There is no logic to suggest that Brexit creates new opportunities to strengthen environmental governance. The UK could have set up its own environmental oversight body whenever it wanted. Indeed, it has had a range of environmental bodies:

- the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution, set up in the 1970s, tasked with identifying environmental problems and potential solutions

- the Sustainable Development Commission, set up by Tony Blair’s government to oversee progress on sustainable development

- the Climate Change Committee, established in the 2008 Climate Change Act.

The Coalition Government also set up the Natural Capital Committee to advise government on “sustainable use of natural capital”.

Moreover, as the case of climate change shows, where the UK led the way in enacting long-term targets, no piece of EU legislation inhibits national enactment of higher standards. And a new UK watchdog would exist only at government and Parliament's pleasure.

Of the three environmental overseers which existed in 2010, only the Climate Change Committee survived the '2010 bonfire of the quangos' – which is why a domestic body can never completely fill the 'governance gap' left by our departure from the EU. Governments can create oversight bodies, but they can abolish them too, so any UK watchdog will only be a partial guarantor of stability and redress.

Gove needs to assure that an environment body – and the standards it oversees – will last

One issue missing from the proposals is how to protect a post-Brexit environment body against subsequent abolition – or that the objectives are amended if they become too difficult. Abolishing bodies and changing objectives, even those set out in legislation, when they get too difficult is a familiar tactic. For example, the Government reacted to its failure on the child poverty targets (with cross-party agreement in 2010) by removing them in the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016.

One possibility would be to give the new body a remit across jurisdictions and make it jointly owned with the devolved administrations. That could make it harder for the UK Government to abolish it.

The Gove plan needs to be clearer on possible sanctions and who can bring cases against the Government

Calling out underperformance can be a real incentive for government to deliver. But whereas the EU has guaranteed sanctions and clear enforcement mechanisms, credible sanctions are much less likely in domestic legislation. Gove will need to set out how he intends on giving his body teeth.

It is also unclear who will be able to bring actions against the Government. For example, it is civil society groups like Client Earth who have brought cases trying to force the Government to meet its air quality commitments. Many non-governmental organisations are worried by the loss of Commission and ECJ oversight and will judge Gove’s plans by their ability to continue to force the Government’s hand through the courts.

- Topic

- Brexit