Gavin Freeguard and Aron Cheung look at what the election result means for government.

No single party can win a majority of seats in the House of Commons.

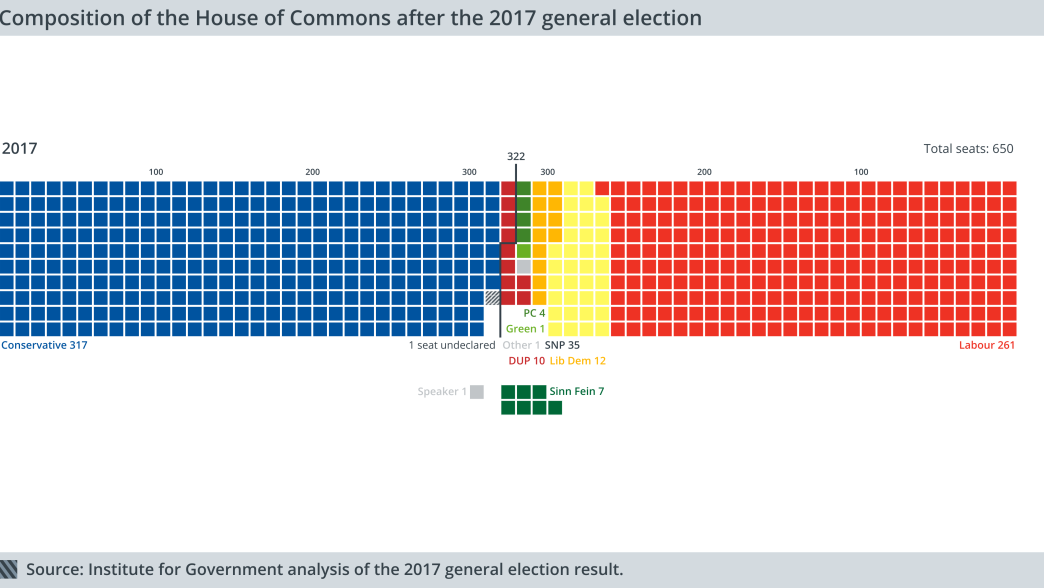

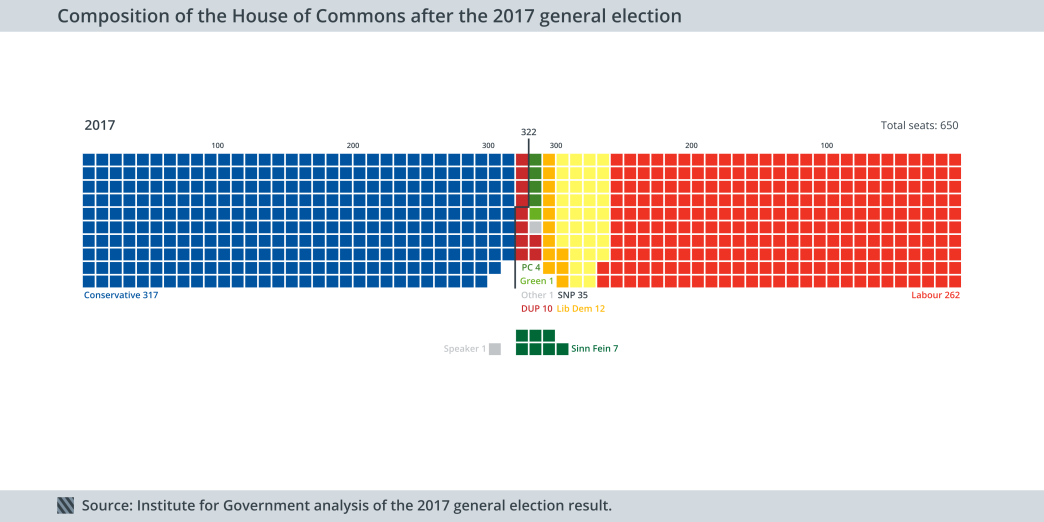

With the last seat, Kensington, having declared, the Conservatives have won 318 seats (down 12 on 2015), Labour 261 (up 29) and the Liberal Democrats 12 (up four). The Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) lost more seats than any other party – 35, down 21.

Given the presence of the Speaker and the fact that high-performing Sinn Féin (seven seats, up three) do not take their seats, a party wishing to form a majority government would need to break 322 seats.

No party has.

As a result, it looks like Theresa May will head a Conservative minority administration, supported by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

It’s not the first time a ‘snap’ election has led to a loss of seats: Clement Attlee’s decision to call an election in 1951 meant Labour lost seats compared to 1950 and fell from office, although Harold Wilson, in both 1966 and 1974, increased the number of Labour seats and continued in government.

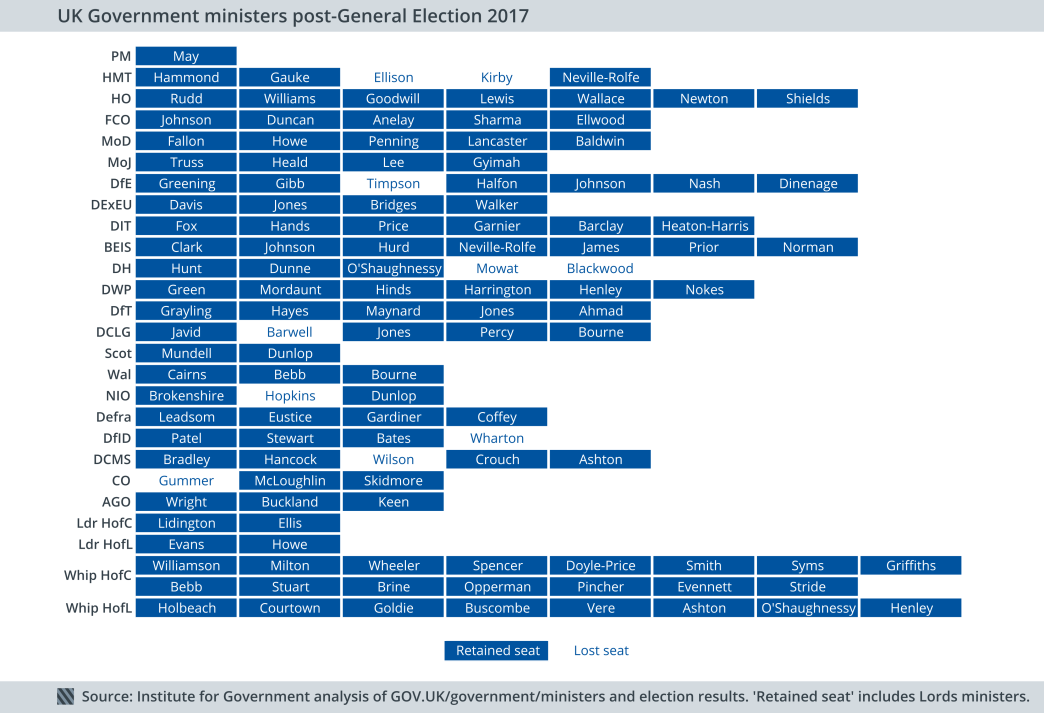

Ten government ministers have lost their seats.

The most significant casualties were Ben Gummer, Minister for the Cabinet Office, and Jane Ellison, Financial Secretary at HM Treasury. Both the Treasury and the Department of Health have lost two ministers. Given the size of the Government’s workload, they will need to be replaced swiftly.

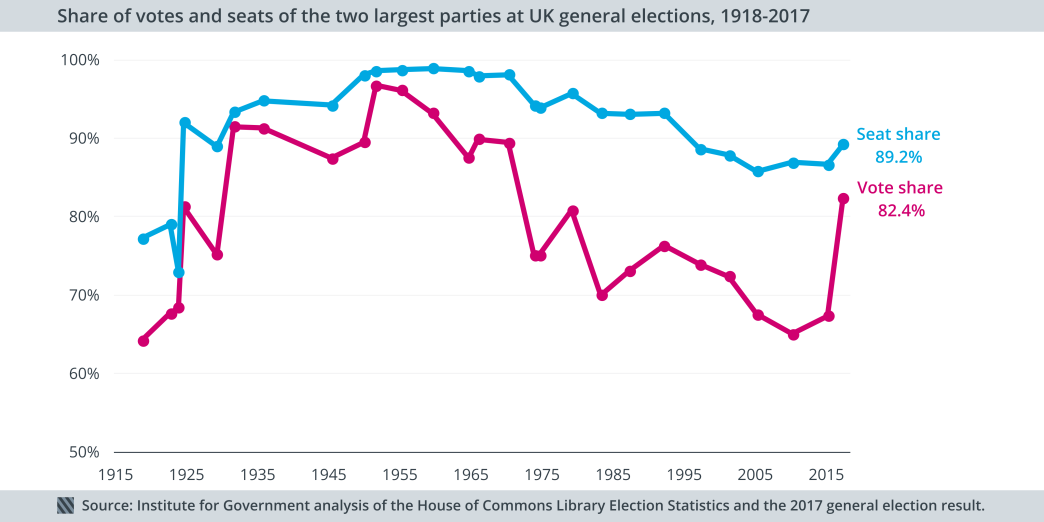

As the polls suggested, two-party politics has returned…

The combined vote share of the two main parties is the biggest since 1970, giving the Conservatives and Labour 90% of the seats in Parliament.

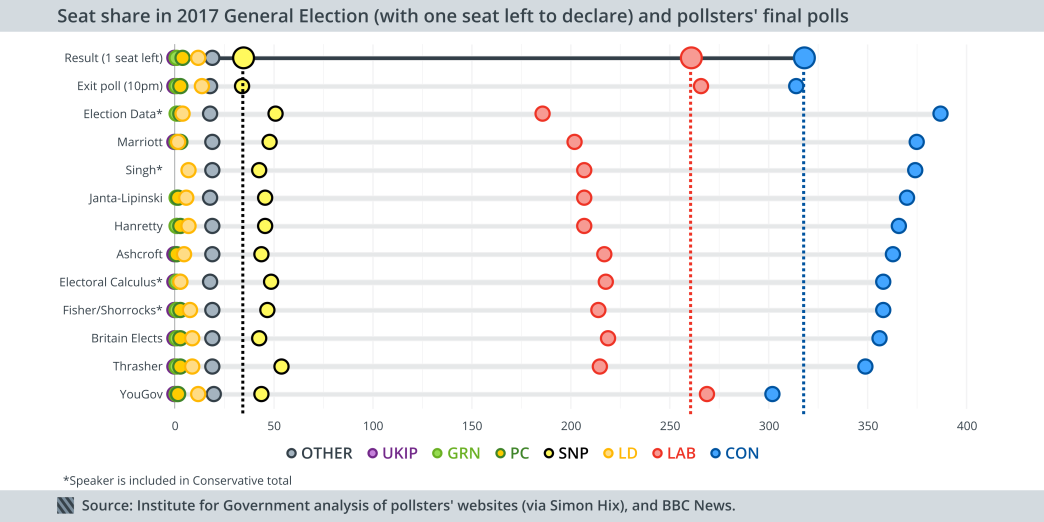

… but Labour’s performance was one that few saw coming.

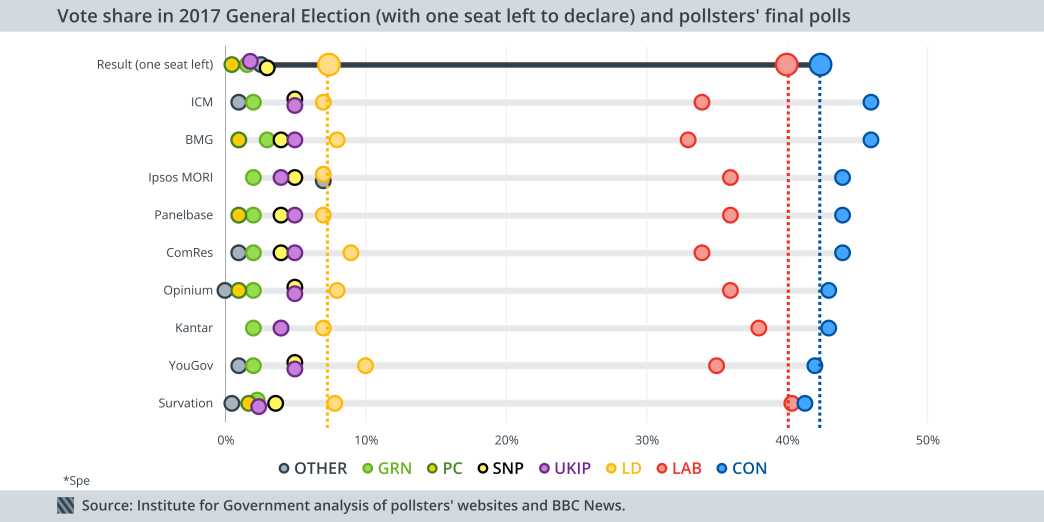

In 2015, analysis of the polls suggested a hung parliament. This time, predictions of seat share pointed towards a Conservative majority – with the exception of YouGov’s experimental model.

Similarly, most polls underestimated the Labour vote share, with Survation coming closest.

This may have had consequences for just how thoroughly government departments prepared for different electoral outcomes.

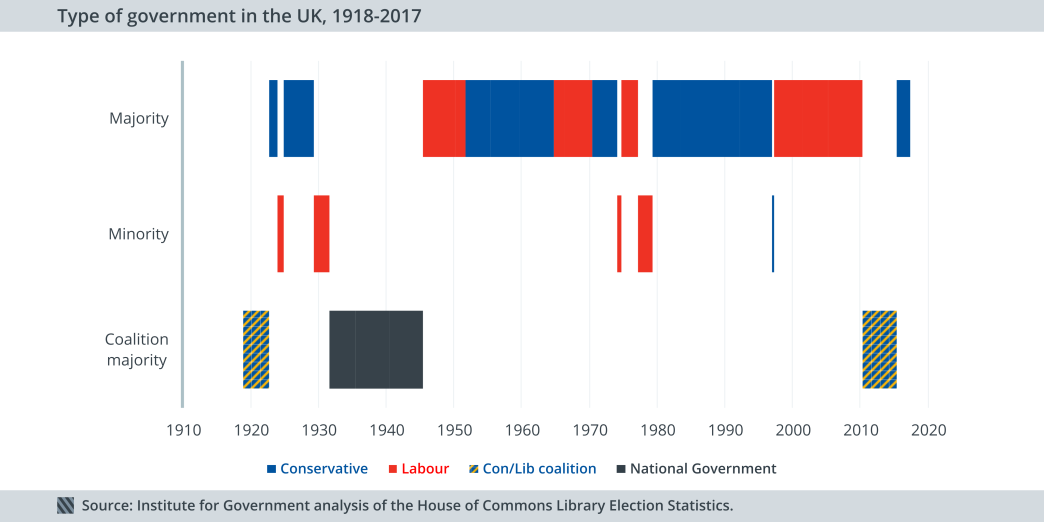

One in five general elections since 1918 has left no party with more than 50% of seats.

Far from being an isolated incident of electoral dysfunction that’s never happened before, the 2017 election is the fifth out of 27 since 1918 where no single party has won a majority of seats in the House of Commons.

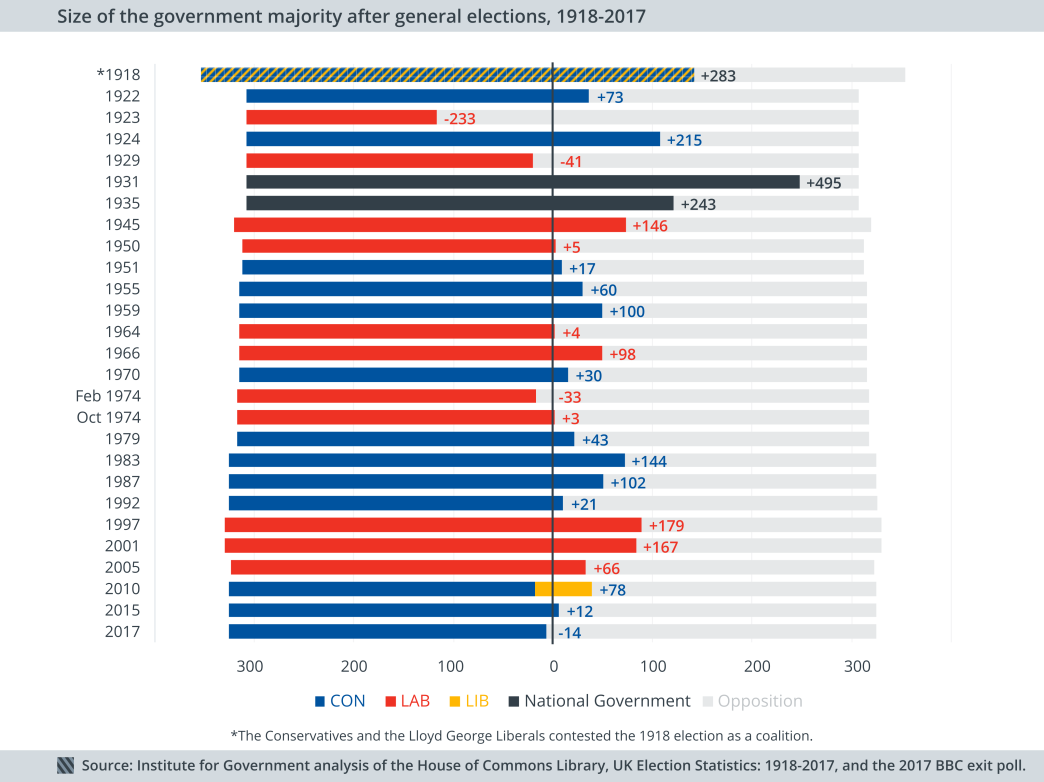

- In 1923, Stanley Baldwin’s Conservatives were 49 seats short of a majority in a House where all three main parties had more than 25% of the seats.

- Labour fell short in 1929.

- The February 1974 election left Harold Wilson’s Labour Party eight seats short of a majority – a second election in October that year gave him a majority of just four.

- The 2010 election left the Conservatives shy of a majority, leading to David Cameron’s “big, open and comprehensive offer” to form a coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

Indeed, as our Director Bronwen Maddox writes in the Financial Times:

There is a danger in viewing a hung parliament as a rare event that threatens to paralyse politics. It would be better to see it as a sign of the complexity of a modern democracy, one which many other countries regard as a sign of health.

These historical examples – some recent, some more distant – show that both coalition and minority government can and have been made to work in the UK. Akash Paun outlines how different types of minority government can operate.