Six things to look out for in the May 2024 local and mayoral elections

These elections will be the last major test of public opinion before the coming general election – but are important in their own right.

On 2 May 2024, voters across England and Wales will head to the polls to elect 10 metro mayors, several thousand local councillors, 37 police and crime commissioners, and all 25 members of the London Assembly. This will be the last major test of public opinion before the coming general election – but these elections are important in their own right.

The 10 metro mayors elected in England’s largest cities, including London, will between them control tens of billions of pounds of public spending. At the local authority level, 2,600 councillors across more than 100 areas will be chosen to deliver key public services at a time of acute financial pressures in local government.

So what are the key things to look out for in these elections? Our devolution team identify six things they will be watching for as the results come in.

1. Will Labour secure a clean sweep of the metro mayor elections?

With Labour’s strong position in the national opinion polls, it would be surprising if any of the five Labour incumbent metro mayors were unseated. Andy Burnham in Greater Manchester, Steve Rotheram in Liverpool City Region, Tracy Brabin in West Yorkshire, Oliver Coppard in South Yorkshire and Sadiq Khan in Greater London all comfortably won their previous elections and are favourites to be re-elected.

More unpredictable are the two regions with Conservative mayors and the three new combined authorities. Andy Street in the West Midlands and Ben Houchen in Tees Valley have both completed two terms as mayor, but the Conservative Party is currently polling substantially lower than in 2017 and in 2021, when these posts were previously elected. Both mayoral areas will be key battlegrounds in the general election so Labour gains here would be heralded as significant.

York and North Yorkshire (which includes Rishi Sunak’s constituency) seems the most likely to see a new Conservative mayor, with North Yorkshire councillor Keane Duncan aiming to become the youngest ever metro mayor. The frontrunner for the North East mayoralty is Labour’s Kim McGuinness, the current Northumbria PCC, but she is facing a strong challenge from independent candidate Jamie Driscoll, current mayor of North of Tyne, a post that is being absorbed into the larger north east role (Driscoll was elected as a Labour mayor before becoming an independent in 2023 after being blocked from the Labour shortlist for the new North East role).

The East Midlands result, where political control of the constituent councils is split between Labour and the Conservatives, could also be close. Conservative candidate Ben Bradley is a local MP and leader of Nottinghamshire County Council, and has long been a vocal supporter of devolution to the area. He faces Claire Ward, previously an MP and junior minister in the last Labour government.

A Labour clean sweep of the 10 mayoralties is therefore possible, if unlikely. But irrespective of their party labels, the 10 successful candidates – plus up to six additional mayors due to be elected next year – will form an influential coalition making a vocal case to the next government for further devolution to and investment in their regions. So while Keir Starmer will celebrate the election of a powerful cohort of Labour mayors on 2 May he may – should he enter Downing Street after the general election – come to conclude that you can have too much of a good thing.

2. Will incumbent metro mayors outperform their national parties?

In the face of falling national polls, the two incumbent Conservative mayors have tried to distance themselves from their national party and Westminster politics more generally. Andy Street explicitly urged voters to “distinguish between party and me” in an interview with the Observer, and has been openly critical of the government for decisions such as the cancellation of the northern leg of HS2. Similarly Ben Houchen said in a social media post in March that he’s “not dictated, whipped or told what to do by any party”. 17 Helm T, ‘West Midlands mayor distances himself from Tories, urging voters to ‘distinguish between party and me’, The Observer, 6 April 2024, retrieved 16 April 2024, www.theguardian.com/politics/2024/apr/06/west-midlands-mayor-distances-himself-from-tories-urging-voters-to-distinguish-between-party-and-me 18 Payne A, ‘Defeat for Ben Houchen is Rishi Sunak’s Biggest Danger Zone’, Politics Home, 6 April 2024, retrieved 16 April 2024, www.politicshome.com/news/article/ben-houchen-and-tees-valley-danger-for-rishi-sunak

In the north east, incumbent North of Tyne mayor Jamie Driscoll is campaigning as an independent having been prevented from standing as Labour candidate by his party leadership. He too has urged voters to "vote for competence” rather than on party lines, while attacking his Labour rival for her record as police and crime commissioner. 19 Jamie Driscoll, Tweet, 16 April 2024, twitter.com/MayorJD/status/1780189703964086587

As directly elected leaders, all the incumbent metro mayors have track records and personal profile they can draw upon to appeal to their electorate. This might well work as a strategy: recent polling revealed that in many cases, metro mayors are better known among the public than local MPs and council leaders. 20 Centre for Cities, ‘Place over politics: What polling tells us about how successful devolution has been to date’, March 2024, retrieved 16 April 2024, www.centreforcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Place-over-politics-March-2024.pdf

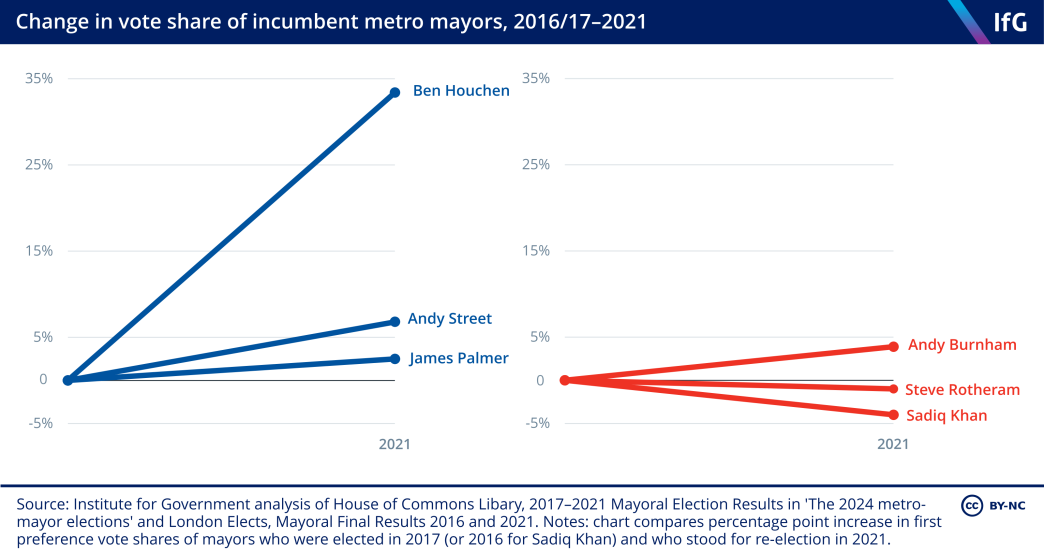

Looking back at the 2021 mayoral elections, all three of the Conservative incumbents standing for re-election managed to grow their share of first preference votes, while the party's share of the national vote in the same day’s local council elections rose by just one percentage point. Most notable was Houchen, whose vote share rose drastically, from 39% in 2017 to 73% in 2021. The three Labour incumbents were comfortably re-elected though only Andy Burnham increased his vote share.

3. What will be the impact of the change of electoral system for mayoral and PCC elections?

Following the Elections Act 2022, metro mayors and PCCs will be elected using the first past the post system (FPTP) for the first time.

Previously, these roles were elected under the supplementary vote (SV) system in which voters could express two preferences. This system required candidates to appeal across party lines for second preference votes from supporters of other candidates.

The supplementary vote was first introduced in 2000 for the mayor of London, before being rolled out to unitary mayors in 2002 and PCCs from 2012. Since then a total of 223 elections have taken place using the system, of which 17 would have had a different result under FPTP (assuming no change in voter behaviour).

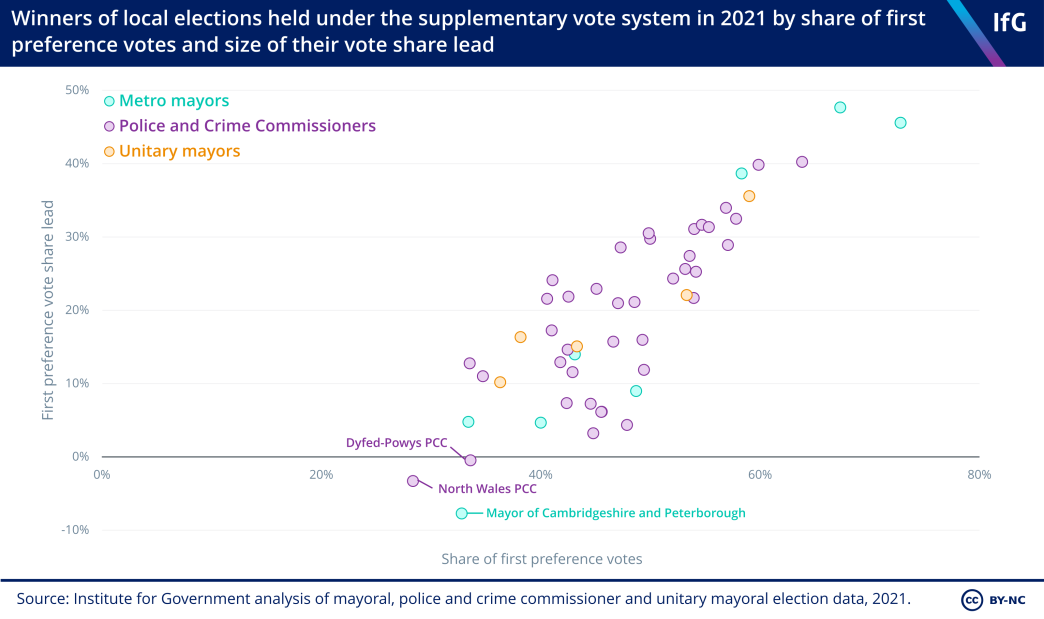

This only happened once for a metro mayor election, when Conservative incumbent James Palmer lost his seat to Labour’s Nik Johnson in 2021 despite winning the greater share of first preference votes. Palmer was defeated due to second preference votes that were transferred to Johnson from the eliminated Liberal Democrat and Green candidates.

Yet across the board, this hasn’t substantially affected one major party over the other. The Conservatives have lost eight elections that that they would have won under FPTP (Palmer’s metro mayor defeat, six PCCs and one unitary mayor), meanwhile Labour have lost seven (three PCCs and four unitary mayors).

It is difficult to predict the change that moving to a FPTP system will have on the outcomes of these elections. Voter behaviour may be different – SV had allowed voters able to predict the last two candidates to give an indication of their ‘real’ preference with their first vote while influencing the outcome with their second. As a result, we might well see the vote share of independents and smaller parties taking a hit this May. At the same time, we could see the election of candidates with a weak mandate – of under 40% of the vote, say – which could undermine their authority as local leaders.

Local and mayoral elections 2024: Why they matter and what to look out for

Sir John Curtice and Sarah Calkin join IfG experts to discuss what is at stake and what to expect in the elections on 2 May.

Register to attend

4. Will turnout in mayoral elections continue its upward trajectory?

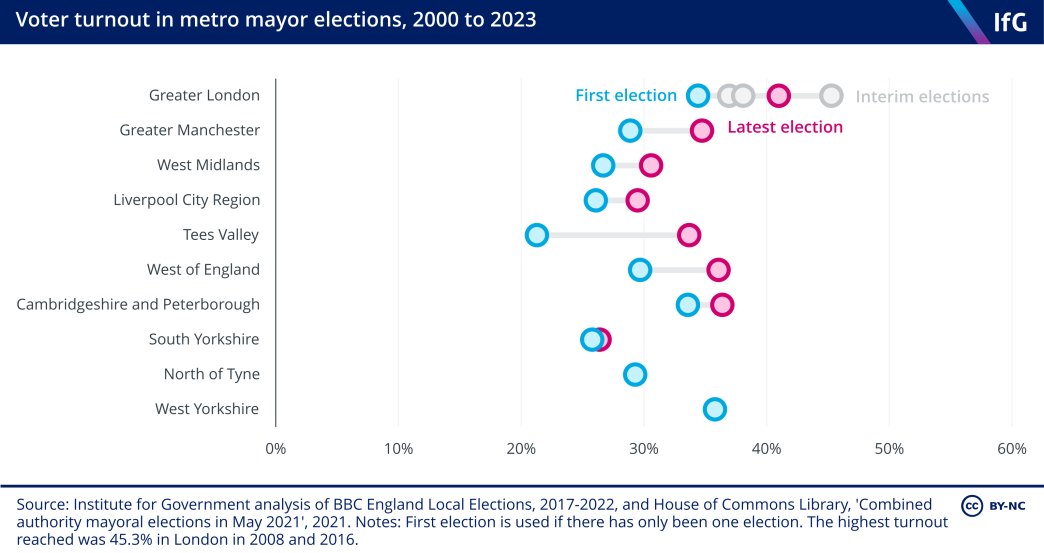

Voter turnout for mayoral elections has historically been lower than that in general elections. The eight 2021 mayoral elections had an average turnout of 35%, against the 2019 general election’s 67%. However, the growing awareness of metro mayors and their role has seen turnout rise in every case between first and second elections. While subsequent elections in London have seen turnout fluctuate, it has never returned to or fallen below first election turnout.

Voter turnout in these elections holds significance for the strength of mandate that the mayor is given, and shows an engagement from voters with what is still a relatively new regional tier of government. A higher turnout means a stronger mandate, empowering mayors to act as champion for their region, both when negotiating with constituent councils within their combined authority and in negotiations with Whitehall.

5. Will the local election results put Labour on course to win the coming general election?

At the previous three transitions of power at Westminster – in 1979, 1997 and 2010 – the party about to enter government made significant gains in the closest local elections to the general election. Following the council elections of 1978, the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher held 50% of council seats across Great Britain. In 1996, Tony Blair’s Labour reached 48%, and in 2009 David Cameron’s Conservatives hit a peak of 46%.

Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour Party currently holds 35% of seats, making it (narrowly) the largest party of local government in Great Britain. However, with fewer than 2,700 seats being contested – around 14% of the total across Great Britain – it is not mathematically possible for Labour to reach the highwater marks set by Thatcher, Blair and Cameron. Of the seats up for election Labour and the Conservatives currently hold approximately 1,000 seats apiece, with the Liberal Democrats on around 400 and the Greens more than 100. 22 Courea E, ‘England and local elections; what’s up for grabs on 2 May and how do predictions look?’, the Guardian, 5 April 2024, retrieved 16 April 2024, www.theguardian.com/politics/2024/apr/05/england-may-local-elections-whats-up-for-grabs-predictions So a strong result for Labour could see them making some 500 gains, but this would only take them to approaching 40% of the national share of councillors.

Despite this, the local elections will be a key test of whether Starmer’s party can convert its high opinion poll lead into gains in an actual election. When the seats up for grabs this year were last fought in 2021, the Conservatives won 40% of the projected national vote with Labour on just 30%. All eyes will be on whether Labour’s vote share this time around reaches the mid-high 40% level that would translate into a sizeable majority in the coming general election.

6. Can the Conservatives hold on to the councils they control in key electoral battlegrounds?

Of the 107 councils holding elections 43 are already Labour-run, 17 are Conservative-run and 10 are Liberal Democrat-run. The remaining 37 are under no overall control with nine led by a Labour councillor. This means there is limited scope for the Labour Party to make a large number of gains.

In the north of England, Labour already controls a large majority of the councils holding elections. The party could realistically take majority control in areas such as Hartlepool, Burnley and Bolton. Elsewhere, it will target areas such as Dudley, Milton Keynes, Southend and Thurrock.

The Liberal Democrats may hope to take control of Dorset council from the Conservatives and will seek to flip no overall control councils where they are the largest party like Brentwood and Wokingham, while the Greens will hope to consolidate their status as largest party in Bristol.

The Conservatives will be preparing for a primarily defensive election, hoping to hold on to the few councils they control outright and also retain seats in those places where they are the largest party but lack an absolute majority such as Rugby, Runnymede and Maidstone. These efforts may prove difficult given the challenge coming from the Reform Party which is currently polling at around 14% nationally. 24 Smith M, Political tracker roundup: April 2024, Yougov, 17 April 2024, retrieved 18 April 2024, https://yougov.co.uk/politics/articles/49179-political-tracker-roundup-april-2024

- Topic

- Devolution

- Political party

- Conservative Labour

- Position

- Metro mayor

- English Regions

- East Midlands East of England North East South East South West West Midlands Greater London Yorkshire and the Humber

- Combined authorities

- Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority East Midlands Combined County Authority Greater Manchester Combined Authority Liverpool City Region Combined Authority North East Combined Authority North East Combined Authority North of Tyne Combined Authority South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority Tees Valley Combined Authority West Midlands Combined Authority West of England Combined Authority

- Project

- Local and mayoral elections 2024

- Publisher

- Institute for Government