Discussions about Brexit negotiations have focused on when they will begin. But it is important to remember that the UK is not the only party at the negotiating table. Nehal Davison looks at who the UK will be negotiating with.

There are four phases of negotiation, some of which may end up happening concurrently:

- Agreeing the terms of the negotiation – when it starts, what is on the table and who is involved

- Agreeing the terms of the divorce, including budget matters and the respective rights of nationals living in the UK and EU, which have to take account 'of the framework for [the UK’s] future relationship with the Union'

- Negotiating the future UK-EU relationship, including trade arrangements

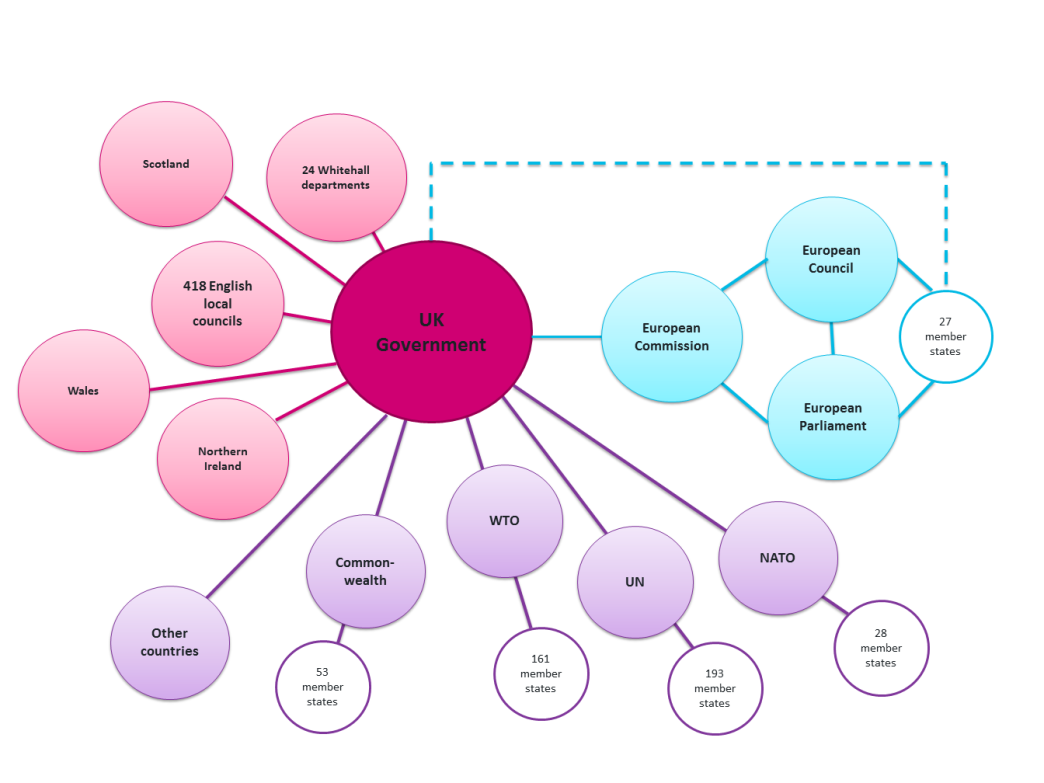

- Establishing the UK’s new relationship with non-EU countries and international bodies, including setting up deals with non-EU markets previously covered by EU trade agreements.

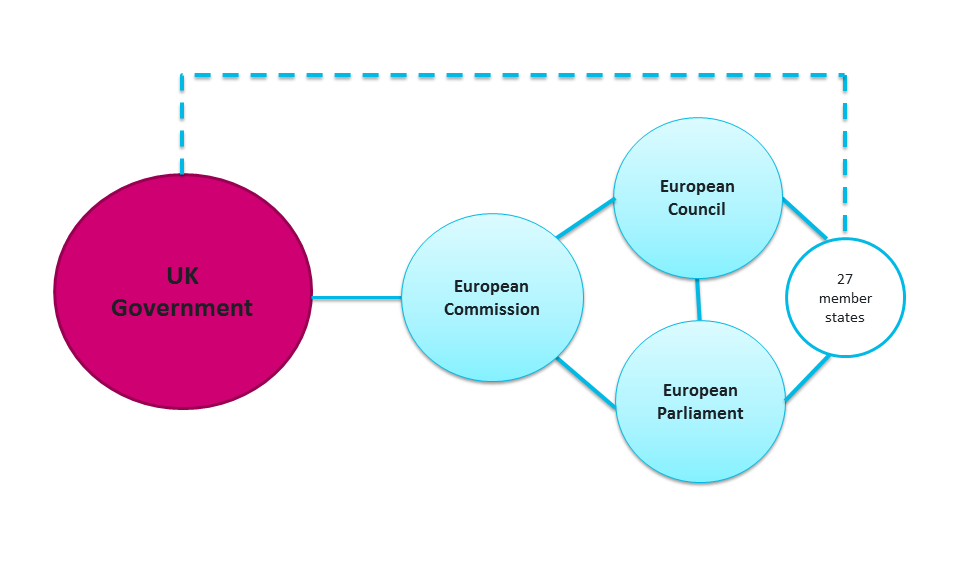

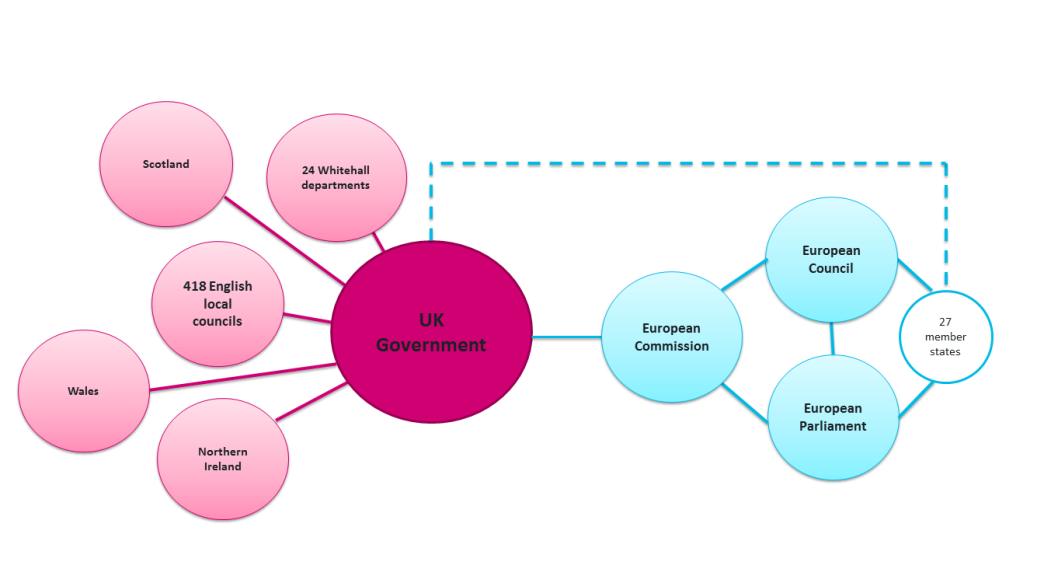

None of these will be simple two-way negotiations between the UK and EU. During each phase the UK Government will need to manage a different combination of domestic stakeholders and engage with a range of different negotiating partners. At their simplest, these negotiations could be thought of as being between the UK Government and the EU.

- Topic

- Brexit