How to approach insourcing and outsourcing: A practical guide for ministers

Key questions you should ask when making decisions on government outsourcing and insourcing.

Introduction

A raft of ’outsourced’ services are delivered by private providers on behalf of government – from IT systems to front-line public services like social care. Some previously outsourced services, including probation, have subsequently been ’insourced’, with government taking back more direct control.

“Ministers have a vital role in setting commercial priorities, making sure that the right suppliers are chosen to address the right requirement and managing contracts to achieve the performance and value required.” – Cabinet Office, ‘Principles for Ministerial involvement in commercial activity and the contracting process’, July 2022

Decisions about insourcing and outsourcing are ultimately part of a bigger decision for ministers: how best to deliver a quality service that offers value for money? You should expect to receive advice from officials on this. But ministers play a hugely important role in the processes of outsourcing and insourcing, setting policy objectives, ensuring delivery functions are involved as early as possible, and keeping track of how their department is monitoring and assessing service performance.

This short guide offers a practical resource for ministers who are considering outsourcing or insourcing a service or who are seeking to better understand and evaluate services that have already been outsourced or insourced. It explores the advantages and disadvantages of putting services out to tender, or returning them to direct control.

136

Davies N and Sasse T, ‘Outsourcing and privatisation’, explainer,

Institute for Government, 7 August 2020, accessed 7 February 2023,

www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/outsourcing-and-privatisation

The guide draws on the Institute’s extensive research into outsourcing and insourcing, as well as the broader procurement of goods and works by government. It sets out the key questions that you should ask when making those decisions. These include:

Outsourcing

- Is it clear why outsourcing is being considered and what trade-offs it may involve?

- Does your department have in-depth understanding of the service under consideration?

- How well is the possible market for the service understood in your department?

- Can you accurately measure the value added by providers of the service?

- Does your department have organisational capability to effectively outsource services?

- Is there the necessary organisational capability and information in your department to manage and oversee contracts?

- How good is your department’s procurement data?

Insourcing

- Are the current arrangements for delivering the service working?

- Has the service been subject to a detailed and thorough review?

- Have you fully considered the different options for insourcing?

- Is the capacity of the department better suited to outsourcing or directly managing a service?

- Is there a clear plan in place for managing the transition of the service?

This guide is designed to supplement existing resources, especially the government’s The Sourcing Playbook 137 Cabinet Office and Government Commercial Function, The Sourcing Playbook, GOV.UK, September 2022, accessed 2 February 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/987353/The_Sourcing_Playbook.pdf and the note on ministerial involvement in commercial activity. 138 Cabinet Office and Government Commercial Function, ‘Principles for Ministerial involvement in commercial activity and the contracting process’, GOV.UK, 27 July 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-to-ministers-on-participation-in-commercial-activity/principles-for-ministerial-involvement-in-commercial… Further details on other useful resources can be found at the end of this guide.

Key concepts

Procurement: The purchase by government of goods, works and services from the private sector, charities and other organisations.

Outsourcing: When companies, charities or other organisations take a greater role in running services on behalf of government. Contracts to do this are usually awarded through a competitive tendering process. Outsourcing is distinct from privatisation, which involves the sale of public assets to private investors who then charge a fee for their use.

Insourcing: When government brings services under greater control, either by bringing them fully in-house or by establishing a wholly or jointly owned organisation to manage them.

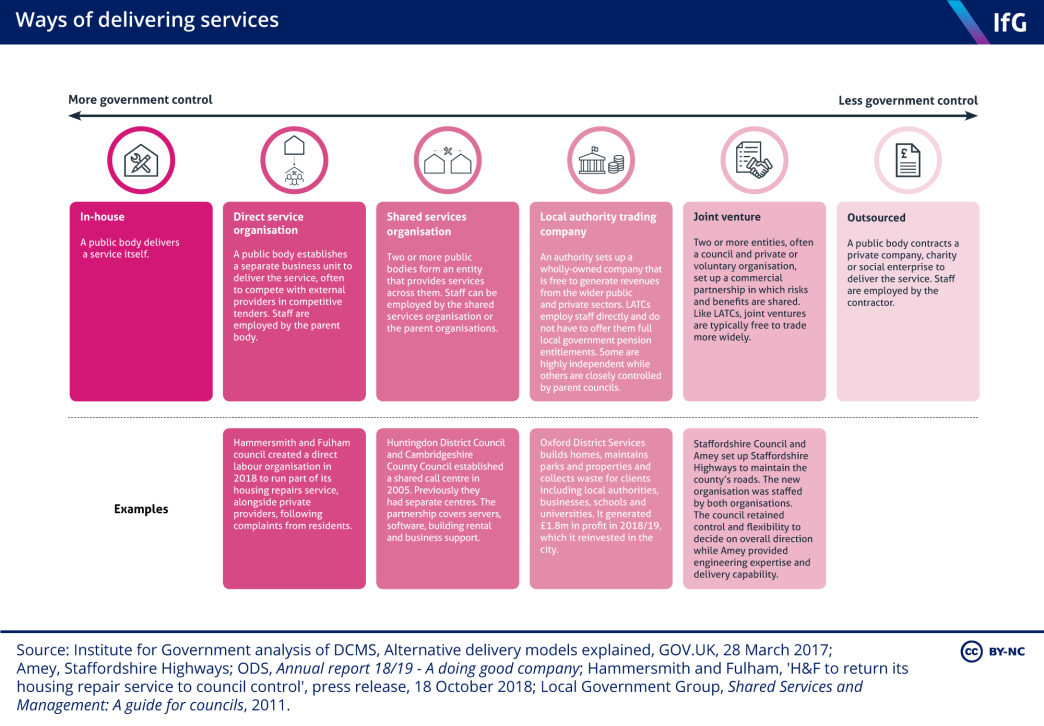

While full outsourcing means limited control for government, and in-house delivery means much greater control, between these two extremes sit a host of other options, all of which involve varying degrees of government control over the service (shown in Figure 1 overleaf). Rather than beginning by choosing either insourcing or outsourcing, when commissioning services you should instead ask what the best means is of delivering a service. The answer may be a mixed option.

The scale of procurement, outsourcing and insourcing in the UK

Although the UK public sector has always bought from the private sector, the introduction of compulsory competitive tendering in the 1980s led to a major expansion in government contracting with private providers. 146 Davies N, Chan O, Cheung A, Freeguard G and Norris E, Government Procurement: The scale and nature of government contracting in the UK, Institute for Government, December 2018, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-procurement Parts of government began to outsource substantial responsibilities to businesses and charities. 147 Davies N, Chan O, Cheung A, Freeguard G and Norris E, Government Procurement: The scale and nature of government contracting in the UK, Institute for Government, December 2018, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-procurement

Central and local government, and other public bodies, procure goods and services from external providers. But procurement accounts for a smaller proportion of central government spending than local government spending, mostly because central government has more areas of responsibility that do not involve procurement (for example, welfare payments or debt interest). In 2021/22, total government procurement expenditure was £379 billion – 36% of all government expenditure. 148 The procurement expenditure figure is based on the Treasury’s PESA estimate of ‘gross current procurement’ and ‘gross capital procurement’ expenditure added together. This is divided by the government’s total managed expenditure to give procurement as a proportion of all government spending.

UK spending on procurement is not particularly high compared to other OECD nations, despite the fact that the UK was an early adopter of outsourcing and is viewed as having one of the most sophisticated public service economies in the world. 149 Davies N, Chan O, Cheung A, Freeguard G and Norris E, Government Procurement: The scale and nature of government contracting in the UK, Institute for Government, December 2018, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-procurement

Procurement also varies greatly between departments. In some, such as the Ministry of Defence (MoD), procurement spending represents over half of total expenditure. By contrast, other departments – like the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) – spend only a fraction of their budgets with external providers.

In absolute terms, the department that spends the most on procurement is – by a considerable distance – the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). Almost all of its £119bn procurement spend in 2021/22 was on the NHS, including the spending of NHS England and Integrated Care Systems on services such as planned hospital and emergency care, and community and mental health services.

It is difficult to establish the extent to which government is starting to return more services in-house. Anecdotally, officials report that insourcing is increasing, and some partial data supports this. For example, a 2019 survey of 208 local authority officers and elected members found that 73% of those surveyed had either already insourced a service or were in the process of doing so.

150

Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-when-and-how-bring-public-services-back-government-hands

And in 2021, at the national level, the government insourced the work of privately run community rehabilitation companies, unifying probation services under the government-run National Probation Service.

151

Davies N and Johal R, Reunification of Probation Services, Institute for Government August 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/reunification-probation-services

Recent interest in insourcing appears to be driven by pragmatic factors, rather than political or ideological motivations. In some cases, such as probation, outsourcing was judged to have delivered poor quality. There have been several high-profile collapses of providers of outsourced services in recent years, including Carillion in 2018. In other cases, insourcing was driven by a desire to increase the flexibility of a service.

There is also now good evidence that the public sector has become more efficient and that the scale of savings achieved from early outsourcing is very unlikely to be repeated. The assumption that outsourced services automatically reduce costs is, according to officials, “outdated”. 152 Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-when-and-how-bring-public-services-back-government-hands

How to approach outsourcing: questions to ask before outsourcing a service

Civil servants will undertake the detailed work on any proposal for outsourcing or insourcing, and evaluation when it is under way, guided by the government’s The Sourcing Playbook. But decisions on outsourcing and insourcing ultimately rest with you. Asking informed questions of officials ensures that you can reach considered and evidence-based decisions on what to do and how to do it.

1. Is it clear why outsourcing is being considered and what trade-offs it may involve?

Usually, outsourcing is driven by a desire to reduce costs and improve quality. But these things do not always go together, and outsourcing may provide one, the other or neither. Being clear on what you want to achieve by outsourcing helps you to ensure you understand these trade-offs.

What is the reason for considering outsourcing?

The theory behind outsourcing is that by handing over the delivery of a service to a provider in a competitive market, downward pressure will be put on costs, providers will be encouraged to meet customer needs and allocate resources more efficiently, and innovation will be spurred. 194 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform But evidence shows that in reality the effects of outsourcing differ from service to service.

In some services, such as cleaning or waste collection, outsourcing has generally resulted in cost savings (although this has sometimes been achieved simply by reducing pay and conditions for staff). 195 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform In other services, such as probation, the available evidence indicates that cost savings have been relatively low. 196 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

The potential savings from outsourcing a service tend not to be as great as they used to be in the early days of outsourcing. Public sector efficiency has improved, in part due to the competitive pressure of outsourcing, meaning that the comparative advantage of private provision has faded. 197 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform If cost reduction is the primary reason for outsourcing, it is crucial you ensure that expectations about savings are realistic and underpinned by evidence. This should include consideration of the TUPE implications of outsourcing a service. 198 Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, A Guide to TUPE Transfers, May 2022, www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/emp-law/tupe/guide#gref

Have potential trade-offs been identified and assessed?

Another reason often presented for outsourcing is that it may improve the quality of service provision, because competition may drive providers to demonstrate they can deliver high-quality services.

199

Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

But the evidence for outsourcing improving quality is much weaker than the evidence on cost savings. Often there has been an excessive focus on outsourcing’s impact on costs and insufficient regard given to quality. Trade-offs between better quality and lower costs have often been downplayed due to an excessive focus on price.

200

Sasse T, Britchfield C and Davies N, Carillion: Two years on, Institute

for Government, March 2020, accessed 2 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/carillion-two-years

After the collapse of Carillion, which held more than 400 public sector contracts, inquiries found that in several instances the contracting bodies chose bids from Carillion that were priced too low to meet the requirements of the contract.

Ensuring you are aware of the potential price–quality trade-off, and being clear about what the purpose of outsourcing is, are crucial to successful outsourcing. According to The Sourcing Playbook, which was published by the government in response to the collapse of Carillion, government should try to “secure the best mix of quality and effectiveness for the least outlay”. To ensure that this happens, you should ask officials for their assessment of how outsourcing a service is expected to affect both its costs and its quality.

2. Does your department have in-depth understanding of the service under consideration?

An in-depth understanding of the service being considered will make it easier to assess how appropriate outsourcing might be, helping you and your officials to make better decisions about how to deliver the service. Officials undertake detailed analysis of specific services, but by asking certain key questions, ministers can test and strengthen the level of understanding of a service.

Is the service inherent to government?

Something that should be considered at the outset is whether a service is so central to the purpose of government that it would be inappropriate to outsource its delivery.

There is little clear guidance on how to draw this line, but work by academics and the US Office of Management and Budget indicates that it may be helpful to consider:

- Whether the service involves making key policy decisions on matters central to the mission of the government – for example, making regulations or setting the budget

- Whether the service is essential to the government’s ability and authority to uphold law and order

- Whether the service is intrinsically related to the government’s duty to protect the public, or where poor-quality provision may place the population at risk, undermining the government’s core role of protecting people. 201 Gash T and Panchamia N, When to Contract: Which service features affect the ease of government contracting?, Institute for Government, January 2013, accessed 2 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/when-contract

If the answer is ‘yes’ to any of these questions, then outsourcing, and the reduced government control this entails, may not be the most appropriate option. However, this is not a blanket rule as prisons, which have been outsourced relatively successfully, would arguably fall foul of questions two and three. You should, though, carefully consider whether outsourcing is suitable.

Does the service have high demand uncertainty or unpredictability?

Providers will price their services according to the risks that they will be taking. A key risk they will consider is the unpredictability of demand, and the impact this will have on their income and costs. It is critical that government allocates risk appropriately. As noted in The Sourcing Playbook: “Inappropriate allocation of risk remains one of the main concerns of suppliers looking to do business with government. It is also one of the most frequent issues raised by the NAO.” 202 Cabinet Office and Government Commercial Function, The Sourcing Playbook, GOV.UK, September 2022, accessed 2 February 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/987353/The_Sourcing_Playbook.pdf

Asking suppliers to take on the risks associated with demand uncertainty can cause a number of problems.

First, service quality may suffer if demand is substantially higher than expected. Good examples of this are the government’s five-year COMPASS contracts for accommodating asylum seekers. In 2012 the Home Office predicted that there would be 20,000–25,000 asylum seekers in need of accommodation, but four years later private providers were accommodating more than 38,000. 203 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

The providers were required through the terms of their contracts to provide accommodation to all asylum seekers. But they struggled to do this, leading to problems with the quality of their service (centres being found to be unsafe) and the providers losing money on the contracts. Such poorly anticipated risks may dissuade providers from taking on contracts in the future. 204 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

Second, if the government outsources on the basis of an expected level of demand that is not reached, it may end up paying for more than providers are delivering. 205 Gash T and Panchamia N, When to Contract: Which service features affect the ease of government contracting?, Institute for Government, January 2013, accessed 2 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/when-contract

Government may also have to make additional investments to ensure service quality or continued provision, especially if providers are unwilling to invest more capital in a service for fear that demand might later fall. 206 Gash T and Panchamia N, When to Contract: Which service features affect the ease of government contracting?, Institute for Government, January 2013, accessed 2 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/when-contract

If there is a lack of clarity about future levels of demand, or if future demand is likely to be unpredictable, you should ask if possible mitigations have been considered. These could include negotiating payment caps (which protect government from making unnecessary payments above demand) and minimum income guarantees (to incentivise providers to take on risk) – though these may well increase costs. 207 Gash T and Panchamia N, When to Contract: Which service features affect the ease of government contracting?, Institute for Government, January 2013, accessed 2 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/when-contract

Will the service be subject to regular policy changes?

If a service is one that is highly political, there is a greater chance that it may be subject to regular policy changes, which may lead to a service being discontinued, changed or scaled back. The government is then likely to have to pay a ‘risk premium’ to providers to deliver these services, increasing costs. It’s also possible that the increased risk involved in running a service subject to policy churn will put off smaller providers from bidding, reducing competition in the market. 208 Gash T and Panchamia N, When to Contract: Which service features affect the ease of government contracting?, Institute for Government, January 2013, accessed 2 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/when-contract

One mitigation in this situation may be to only use short-term contracts, so that there is less chance of major policy change occurring during the lifetime of the contract. But this will need balancing against the greater attractiveness of longer-term contracts to potential providers, as they give them greater confidence and incentivise investment. 209 Gash T and Panchamia N, When to Contract: Which service features affect the ease of government contracting?, Institute for Government, January 2013, accessed 2 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/when-contract

If a service is likely to be subject to policy churn, and if these mitigations are not suitable, then you may decide that government is better placed to deliver the service itself, as more secure funding can help it to better manage the risk.

3. How well is the possible market for the service understood in your department?

An essential precursor for successful outsourcing is a competitive and healthy market. 210 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform Available evidence suggests, on average, a 2.5% lower cost to the government for each additional bidder for a contract. 211 Pope T, ‘The government must bring an end to its risky Covid crisis procurement’, Institute for Government, blog, 5 February 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/government-must-bring-end-its-risky-covid-crisis-procurement

When a decision is being made on outsourcing, officials need to have a good knowledge and understanding of the potential market of providers for delivering that service. Questions from the minister can help draw out how good this understanding is and expose any gaps.

Is there an existing market of providers for the service?

If there is no existing market of providers for the service, outsourcing is far riskier. As well as less competition to encourage better quality and lower costs, there is also less data for government to draw on to understand how it might gain from outsourcing – or where the problems might come from.

For these reasons, this is one of the criteria used by The Sourcing Playbook for identifying “complex outsourcing” projects that require more oversight. Ultimately, outsourcing in this context means relying on a provider to be better managed than government is when delivering the service, and being able to make staffing decisions more flexibly than government.

These are risky things to rely on. For example, when probation services were first outsourced, there was no data on which to base the contractual model, which was very costly both for the providers and government. You should ensure that officials have assessed a market of providers is already in existence.

Is the market for the service competitive and well-developed?

Generally, in cases where a service has been outsourced to an existing competitive market of high-quality providers, government has seen some efficiency gains and improvements in quality. For example, when the government first outsourced its IT and other back-office services, it was able to outsource to a market with much greater expertise in those services than existed within government, helping some bodies achieve significant savings. 212 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

But in cases where potential providers have less experience or expertise in delivering a service, there is a greater risk of poor performance or of the quality of the service falling as a result of outsourcing. For example, no providers had previously overseen the full management of offenders in the UK when the government decided to outsource some probation services. And though some providers did have experience of providing specific services to those on probation, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) decided to largely exclude these suppliers from being prime contractors. This contributed to widespread failures to produce a quality service once probation was outsourced. 213 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

Where services were outsourced to less well-functioning or competitive markets, suppliers have been more likely to engage in opportunism, meaning greater risk of problems with performance. For example, the market for electronic monitoring of offenders was small and dominated by two major providers, meaning it was relatively uncompetitive. When the MoJ’s contracts with these providers came up for re-tender in 2013, they discovered “significant anomalies” in billing practices, including charges for electronic tags that had never been fitted. Both providers later withdrew from the tender process, meaning only one other provider remained. 214 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform Even where providers have had serious failures, they can still end up winning further contracts if they have few competitors. 215 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

The Covid pandemic also illustrated how a lack of competition can cause problems in procurement. Far more contracts than usual were awarded directly to suppliers – understandably (at least early in the pandemic) as the government needed to move fast. But this contributed to the poor value for money secured by government, and the low quality of some of the goods delivered. 216 Pope T, ‘The government must bring an end to its risky Covid crisis procurement’, Institute for Government, blog, 5 February 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/government-must-bring-end-its-risky-covid-crisis-procurement

Outsourcing may still be an effective option where there is a less-developed market if you are prepared to take steps to create one – for example, through early engagement or piloting. This has happened in the case of some services, such as waste collection. However, this approach is likely to involve a transitional period during which some services might experience a dip in quality, which you may view as inappropriate or as politically unviable. 217 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

Has early market engagement been conducted?

Early engagement with possible providers for a service is critical. The earlier that government discusses with potential providers what it wants from a service, and how it can be delivered, the stronger the likelihood that outsourcing will be successful. Especially for complex projects, early market engagement offers a forum to discuss the deliverability of specific requirements, and any potential challenges and risks. It can also shed light on which aspects of a service it makes sense to outsource, and whether there are any parts of a service where outsourcing may be difficult. Early engagement is also important when there is a weak existing market. For example, in 2012 a contract between the British Army and Capita for recruitment was signed with little prior market engagement to understand how new recruitment processes would work in practice. Recruitment targets were not met, although progress did subsequently improve. The Public Accounts Committee called the Army’s approach to procurement “naïve”. 218 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

You should check whether early market engagement is happening. Ministerial engagement with current and future suppliers can help to grow and shape markets, as well as boost market intelligence, as the government’s guidance to ministers notes. 219 Cabinet Office and Government Commercial Function, ‘Principles for Ministerial involvement in commercial activity and the contracting process’, Further advice, GOV.UK, 27 July 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-to-ministers-on-participation-in-commercial-activity/principles-for-ministerial-involvement-in-commercial…

4. Can you accurately measure the value added by providers of the service?

A core characteristic of successful outsourcing is measuring the value added by a provider. If this cannot be easily done, it can cause problems both during the procurement process (as it becomes harder to write and price contracts) and after the service has been outsourced (as it becomes harder to assess the quality of the provider’s service). 220 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform An inability to measure value added can also cause difficulties for providers, including losses resulting from circumstances over which they have no control.

Is value easily measurable for this service?

The value added by a provider is easier to measure for some services than for others. Various services involve easily measurable outputs or outcomes that can be defined and used to judge performance, such as frequency of waste collection or standard of cleaning.

221

Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

In prisons, metrics include violence rates or number of educational activities offered, and in some health services value can be easy to measure: number of operations, outcomes for patients, or length of hospital stay, for example.

222

Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

One good example of how measurement is crucial to successful outsourcing is the Department for Education’s outsourcing of the Teachers’ Pension Scheme to Capita in 1996. The contract covered maintenance of records, pensions payroll, accounting and customer management. When the government reviewed this in 2008, they found that Capita had reduced operating costs by 48% while maintaining a high-quality service. The review concluded that “robust performance metrics”, such as response times and customer satisfaction data, had helped lower costs while maintaining quality. 223 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

But in some services, determining performance is more complicated, either because it depends on other services or factors beyond the provider’s control (discussed below), or because it is less obviously defined. Where performance is difficult to measure, and it is therefore harder to write contracts and to assess providers, you may decide that outsourcing is not the best option.

Is the performance of the service strongly affected by external factors?

For some services, outcomes are difficult to measure because they are highly dependent on circumstances beyond the scope of the service, and therefore outside the control of providers.

Unemployment services are one good example of this. A scheme run between 2011 and 2016 to help unemployed people back into work – the Work Programme – ran into difficulties that the National Audit Office (NAO) ascribed, in part, to contracts that were not well constructed to measure or reward performance. Because providers were paid partly on the basis of employment outcomes, which could be affected by a range of external factors – like the state of the economy, or regional labour markets – there was little real incentive to assist the most disadvantaged jobseekers. This phenomenon, known as ‘creaming and parking’ (directing resources towards the easiest to help and minimising resources given to those least likely to succeed) persisted even after DWP altered payment terms to try to address it. 224 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

Another good example is probation. Rehabilitation outcomes depend on a host of external factors and organisations, such as housing and welfare services, the police and courts. This meant that it was difficult to measure value added by providers, so the MoJ struggled to set out in contracts the quality of service it expected. Some of the metrics used incentivised suppliers to game the system to avoid contractual penalties. 225 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

For services where outcomes and the value added by the provider are harder to measure, there are some possible mitigations against problems. Government could try to write detailed contracts using proxies for performance, ensuring they do not create perverse incentives. And quality could be monitored by inspections, alongside the use of data to draw up counterfactual models showing how the service might have been expected to work if not outsourced. But these mitigations are not likely to be straightforward, which means you should give serious thought to whether they are sufficient, or whether outsourcing may not be the right option for the service in question.

5. Does your department have organisational capability to outsource services effectively?

When a service is outsourced, it requires the government to work in different ways: to run a procurement process, assess bids, negotiate contracts and manage performance. This requires commercial skills and expertise, which can be uncommon skillsets in government. Ensuring that you have this kind of expertise in your department – or that you have a clear plan to obtain it – is therefore key to making government an ‘intelligent purchaser’ that can outsource smoothly.

Does your department have the necessary commercial skills?

Historically, commercial skills and expertise have been an area of weakness within central government. But standards across government have risen following a move to recruit senior leaders with extensive commercial experience via the Government Commercial Organisation, as well as the establishment of the Government Commercial Function to co-ordinate work across departments. A new Assessment and Development Centre and its accreditation and assessment process have also helped to drive up standards.

226

Sasse T, Britchfield C and Davies N, Carillion: Two years on, Institute for

Government, March 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/carillion-two-years

But there is still work to be done. Often it is more junior staff who are responsible for the management of contracts, and they can lack the confidence and expertise needed to challenge suppliers. Less improvement has been seen among these more junior staff, meaning that there can still be some capacity gaps when it comes to managing contracts. And though the improvement of commercial skills at senior levels is welcome, there is still more to be done to fully integrate these officials into departmental leadership teams and ensure they get early sight of policies.

227

Sasse T, Britchfield C and Davies N, Carillion: Two years on, Institute for

Government, March 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/carillion-two-years

Successful outsourcing requires the ability to judge robustly the quality of bids and potential providers. Past research by the Institute for Government has found that the importance of cost has often been prioritised over quality, with only limited or “superficial” quality metrics used to assess bids. But there are now better criteria in use within government to help officials assess this, including the detailed guidance on taking account of social value.

228

HM Government, ‘Procurement policy note 06/20: taking account of social value in the award of central government contracts,’ GOV.UK, September 2020, accessed 3 March 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/procurement-policy-note-

0620-taking-account-of-social-value-in-the-award-of-central-government-contracts

As well as commercial skills and experience, judging the quality of bids also requires familiarity with procurement regulations. But often, officials working on this are relatively inexperienced and short on time. For example, although it is very difficult under regulations for a provider to be excluded from a bidding process, it is possible for government to use a provider’s past performance against published KPIs to question them in future bidding processes. 229 Cabinet Office, ‘Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for government’s most important contracts’, GOV.UK, last updated 13 February 2023, accessed 3 March 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/key-performance-indicators-kpis-for-governments-most-important-contracts But staff need time and capacity to properly analyse KPIs when planning future contracts.

It is important for you to press your officials on whether there are sufficient commercial skills and experience within the department to outsource a service and judge the quality of bids.

6. Is there the necessary organisational capability and information in your department to manage and oversee contracts?

A contract being negotiated and agreed is not the end of the outsourcing process. A department will also need a plan to oversee and manage the contract before the contract is let. Effective management of a contract also plays a crucial role in ensuring good performance.

Day-to-day contract management will be handled by civil servants, but ministers should ensure that the most important contracts have clear performance indicators, and that suppliers are meeting their targets.

As the government’s guidance on ministerial involvement in commercial activity and the contracting process states, ministers’ involvement should be particularly focused on high-profile bids and major contracts where they should seek to be “kept informed of performance… and may wish to be involved in high level discussions on performance”. You should make sure that officials know to come to them if problems arise and make it clear to officials at what stages they want to be kept appraised of progress.

Does government have enough independent information about cost and quality to monitor performance?

Good management of a contract requires good information, particularly about cost and quality. Where this information is not collected, or is not collected independently of providers, it can make it harder to monitor performance and therefore to manage the contract. One example of this kind of problem was with the MoJ’s outsourcing of electronic monitoring. Only when the contract came up for re-tender in 2013 were anomalies in billing practices discovered, following reports from a whistleblower. As the MoJ had not had an independent source of data on the service, it had used the provider’s information. 230 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

In 2014, the NAO, conducting a review of more than 70 contracts, found that government was often reliant to too great an extent on data from providers.

231

Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

Though government has now improved in this area, research by the Institute has suggested that providers can claim commercial confidentiality not to share vital information – and government can still be too willing to accept this.

232

Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform

Ensuring that there will be adequate information available – and from independent sources – to monitor provider performance is key. This is something you should encourage officials to think about prior to the outsourcing process beginning, so that plans for obtaining information can be drawn up.

Does the government have sufficient contract management skills?

Management of contracts also requires specific skills and expertise, and is crucial to ensuring that outsourcing secures the savings and benefits it is supposed to.

But contract management can be left to more junior civil servants, who may not have the experience or confidence to challenge providers and may not have been involved in contract negotiations. There is also often high turnover in these roles, meaning that new contract managers must quickly get up to speed. This contrasts with the approach taken by many providers, who manage contracts at more senior levels and have more stability in their staffing. This puts providers at an advantage over contract managers within government.

In the private sector, contract management is often a dedicated job, not something done on top of other duties. There is training available for civil servants to improve their contract management skills, but you should think about how your department can be brought in line with private sector practice. You should regularly ask for figures on the take-up of this training within your department, and encourage officials to undertake training, while benchmarking these figures against other departments. You should also enquire about how your department will ensure continuity and knowledge transfer between those who negotiate contracts and those who manage them.

7. How good is your department’s procurement data?

It is critical that the government – as well as public services and providers – can answer questions about how much is being spent on procurement, what is being bought, and who the providers are. By having this information, government can make better-informed spending decisions, reduce waste, and make significant savings, as well as report adequately to parliament. But the quality of data on procurement and outsourcing has historically been poor.

233

Davies N, Chan O, Cheung A, Freeguard G and Norris E, Government Procurement: The scale and nature of government contracting in the UK, Institute for Government, December 2018, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-procurement

Better data on procurement and outsourcing has multiple benefits. It can improve accountability, offer greater market insights, and increase competition and lower prices. One estimate shows that greater transparency about procurement contracts reduces the likelihood of single bidders by 2% and makes tendering between 0.14% and 0.25% cheaper. Scaling those savings across the government’s whole procurement spend could result in hundreds of millions of pounds of savings. 234 Davies N, Chan O, Cheung A, Freeguard G and Norris E, Government Procurement: The scale and nature of government contracting in the UK, Institute for Government, December 2018, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-procurement

Day-to-day analysis and collation of data will be undertaken by civil servants. But ministers can play a crucial role in encouraging the importance of high-quality data and insisting on the need for robust data architecture. Asking officials to regularly assess the quality of their data, and checking progress on plans for its improvement, can help drive up standards.

How to approach insourcing: questions to ask when considering whether to insource a service

While successive governments over the past 40 years have extended the role of the private sector in delivering services, there is growing interest in insourcing: bringing services back into government hands. Insourcing of services has happened at the local and national level, such as the decision to bring probation back under government control.

Insourcing can offer benefits, including over the quality and flexibility of services. But the transition away from outsourced services can be disruptive, and have other drawbacks – for example, the private sector has a capacity for expertise and innovation that government does not.

In balancing these risks and opportunities, decisions on how best to deliver services should be approached on the basis of rigorous evidence and analysis, rather than ideology alone. Officials will undertake the detailed, day-to-day work on proposals for insourcing, guided by The Sourcing Playbook. But decisions will ultimately be your responsibility. Below, we set out questions that you should ask of officials and the advice they have been given, to help them reach evidenced decisions.

1. Are the current arrangements for delivering the service working?

Insourcing a service, just like outsourcing, can be a disruptive process, so it is important that any decision to do this has a clear reason – normally that the current arrangements for delivering the service are not working, and so something different should be tried. Civil servants will be able to offer advice, but you need to ensure that all the different aspects of the current service’s performance – and what needs to change – have been teased out.

What is the health of the market for this service?

If competition in a market dries up, then failures in outsourcing are more likely. A good recent example of this is a Scottish government contract for escorting prisoners. An eight-year contract was awarded in 2018 to the only bidder after two other companies – G4S and Serco, both of which had experience of delivering this service – pulled out. 243 Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/governmentoutsourcing-when-and-how-bring-public-services-back-government-hands When there are fewer companies willing to bid for a contract, some of the potential benefits of outsourcing are not realised.

A lack of providers in the market can also allow those that remain to ‘lock in’ buyers, pushing prices up because there is little competition and because of the high potential costs of changing provider. This means that government ends up not getting either the quality or price that it wants from the service.

If there are few providers – and especially if there are few providers with experience of delivering the service – then insourcing is likely to be a good option.

How much flexibility is needed for this service – and does that degree of flexibility exist?

When a service is outsourced, government has less direct control over it. This can make it harder, as well as more expensive, to make changes to the service, such as its scope or its design. Flexibility can be written into contracts, but in general will push up prices, as providers have to factor in greater risk and uncertainty. And where a low-cost contract with little flexibility is agreed, and changes are subsequently required, providers can charge substantial ‘contract variation charges’, which are often what makes a contract profitable for a provider.

244

Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/

government-outsourcing-reform

It is also more difficult to make effective subtle changes to the scope or design of a service through a contract renegotiation than to do so directly. Often discussions will be legalistic and narrowly focused on terms and phrasing in the contract specification, particularly when a relationship has become adversarial. It can be difficult to discuss, or reflect on, changes to how a service is run, and the cost attached to each change can act as an incentive against testing new approaches. 245 Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/government-outsourcing-public-services-back-government-hands

Insourcing offers greater control over a service, meaning government has the freedom to increase or decrease service provision in response to fluctuating demand, change the service design where a shift in policy direction is warranted, or cut costs when overall budgets are under pressure, without having to negotiate changes to a contract.

The more likely a government is to need flexibility to change a service, the more likely bringing a service in-house will be the best option. Ensuring that officials have considered the level of flexibility needed for a service – in terms of its scope and design – is key.

2. Has the service been subject to a detailed and thorough review?

Before deciding whether to insource a service, it is crucial to understand how the service is operating on a day-to-day basis. This is especially important for those services that have been outsourced for a long time, meaning government has retained little understanding or knowledge of how to manage it. It is difficult to develop a long-term plan for a service to be brought back in house if the service itself is not well understood.

Are the business model, costs, and staffing for the service well understood?

If the government does not fully understand key aspects of the service it is seeking to insource, then major problems can arise. For example, if the business model is not understood by officials then there is a risk of inaccurate assumptions about cost, leading government to take on more risk than it intends when it insources the service.

Officials need a detailed understanding of:

- demands on the service

- staffing patterns

- employment terms and conditions

- the wider supply chain

- the needs of different service users.

Civil servants working on the potential insourcing of the service should be able to demonstrate that they have reviewed and assessed these aspects of the service in detail, or that there is a plan for how to do so.

Have the current providers had their knowledge and experience tapped?

Much of the knowledge and detailed understanding of the service will lie with the current provider. Not tapping into this when considering insourcing the service would be unwise. But it is not always easy to do. Often bodies insource a service because it is failing, efforts to improve performance have not worked or the relationship has broken down. Suppliers, in turn, might have little incentive to co-operate once they know there is no chance of renewal. 246 Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/government-outsourcing-public-services-back-government-hands

Ultimately, though, the current provider is still best placed to provide detailed knowledge about the service. As long as the insourcing process is dealt with fairly, suppliers should co-operate to maintain their reputation in the market and ensure they are considered for future contract opportunities, particularly if they retain other contracts. 247 Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/government-outsourcing-public-services-back-government-hands

It is important that your officials have either spoken to the current provider about the service, or have a plan for doing so, taking into account any potential sensitivities.

3. Have you fully considered the different options for insourcing?

Insourcing can take different forms, from in-house control to a trading company or joint venture. Each of these options will have pros and cons, and there is no hard and fast rule for what works best. It will depend on the particular service under consideration. Ministers will receive advice on which option is thought to be best for the service, but should check that other options have been assessed robustly.

Have the trade-offs involved in different forms of insourcing been assessed?

Full insourcing gives the greatest degree of control over a service, which may be preferable, especially for services that require significant flexibility or integration with other services. But full insourcing may also involve higher staff costs, especially as a result of public sector pension schemes, which are generally more costly than those in the private sector. Depending on the precise costs involved, this could make full insourcing either risky or unaffordable. At the same time, taking on staff through a fully insourced service may have benefits, such as improved staff retention and clearer career progression, which can improve motivation in the longer term.

By contrast, insourcing in the form of joint ventures or trading companies can limit increases to staff and pension costs – though some of the possible long-term benefits of these things may then be lost. Joint ventures may also deliver revenues that can then be invested in other areas of work, and can allow government to continue benefiting from the scale and expertise of a private sector provider, while exerting greater control over some aspects of the service. However, ministers should be cautious of using them, with some senior officials with commercial expertise warning in interviews with the Institute that there are few, if any, successful examples of joint ventures.

You should weigh these trade-offs and consider all options to find the one that is best for the specific circumstances of the service and the policy objectives being pursued.

4. Is the capacity of the department better suited to outsourcing or directly managing a service?

Insourcing requires greater day-to-day management of the service on the part of the government, but there may not be the capability within government for this. There may not be many people with the necessary skills, or experience of managing a particular service (and especially those that are large or complex). Getting the right people in place is key, but this can require forethought – to assess existing capabilities and plan for any necessary hires. You need to ensure that this work is being undertaken by civil servants.

Although outsourcing gives government less control over a service, it still needs to manage the contract and the relationship with the provider. This requires commercial skills, the lack of which has been repeatedly found to be a reason for failures of outsourcing. While the Cabinet Office has improved capability across central government in recent years, there remain problems with commercial skills in other parts of government, especially local government and public bodies. 248 Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/government-outsourcing-public-services-back-government-hands

It is therefore crucial for you to ask officials to assess the capability and capacity of the department, and whether it is better suited to directly managing or outsourcing a service.

Is there the capability to manage the service under current arrangements?

Private providers are more likely to have experienced commercial professionals, with expertise in negotiations and legal issues, putting them at an advantage over government bodies with less experience or deep knowledge. This is particularly the case for complex, long-term contracts where agreeing payment structures and liabilities can require deep expertise.

Once a contract has been agreed, it still requires management, which must be adequately resourced. As well as appropriate time devoted to contract management, there needs to be confidence among those managing contracts; for example, to ask for management information or seek answers from providers when contracts are faltering.

Where an organisation lacks the skills and capacity to successfully negotiate and manage contracts, insourcing is likely to be a better option. Running the service itself will bring its own challenges, but the organisation will be less exposed to the potential hazards of the open market. It is likely to be more straightforward, and cheaper, to build delivery capability than commercial capability – and if the service is failing, it will be easier to get a grip of the problems directly than through a potentially adversarial contractual relationship. 249 Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/government-outsourcing-public-services-back-government-hands

These issues may be less immediate for central government, given efforts to boost commercial capabilities. But you should reflect on what capability there is to negotiate and manage contracts – and whether it is enough – when considering whether insourcing might be a better option.

What existing capability is there to manage an insourced service?

Management of an insourced service will be very different to the kind of contract management needed when a service is run by a private provider. The capability to manage a large and complex service, and experience in managing a specific service, may not be present in government, especially if a service has been outsourced for a long time. As well as having these skills, it is likely there will be a need for managers who are familiar with undertaking transitions, and who will be able to bring all those involved in the process of insourcing along with them.

For example, when probation was insourced to the MoJ, key departmental figures had previously been involved in the outsourcing of the service, and played a key role in helping successfully manage the transition. 250 Davies N and Johal R, Reunification of Probation Services, Institute for Government, August 2022, accessed 3 March 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/reunification-probation-services

You should ask officials early on to assess whether these skills and experiences already exist within government, or if it is likely they will be need to be recruited. This needs to happen early on in the process of considering insourcing as it may take time to plan necessary recruitment.

Are there plans for boosting management capability for insourced services?

If the assessment of officials is that additional management capability would need to be bought in if a service were to be insourced, then ministers should ensure that their department has a workable plan for doing this. Getting the right people in may not be easy. Senior staff who have helped run the service in its outsourced form may not wish to make the transition. Recruiting people with the relevant skills and experience from elsewhere in the private sector is an option, but can often take time – so must be started early on.

Building capability may also be costly. In some roles, there can be a large gap between private and public sector pay – and to bridge this gap and bring in expertise, you may need to be willing to allocate additional resource.

Does your department have clear plans for how performance will be monitored?

The performance of outsourced services is measured using KPIs, but this does not happen so systematically for insourced services. If a service is insourced, there needs to be a plan for how its performance will be assessed. This may mean keeping the same KPIs, or devising new ones so that they reflect the new arrangements for delivering the service.

Because decisions to insource are usually taken at the departmental level, it is critical for you to ensure your team has a plan for monitoring performance of an insourced service in a clear and consistent way, as is the case with outsourced services.

How to approach insourcing: questions to ask once a decision to insource has been reached

5. Is there a clear plan in place for managing the transition of the service?

Insourcing services, in whatever form delivery takes, will entail a transitional period. This can be difficult, and it may be that some problems do not emerge or cannot be addressed until the day that the new arrangements are in place. For example, despite probation being insourced with virtually no disruption to day one services, there are ongoing challenges around the cultural integration of staff from independent providers into the public sector, and harmonisation of terms and conditions. 253 Davies N and Johal R, Reunification of Probation Services, Institute for Government, August 2022, accessed 3 March 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/reunification-probation-services

It is crucial that officials draw up plans for how outsourcing arrangements will be exited, and how the transition will work, and your oversight can help this happen.

Are there plans for the workforce?

When a service is insourced, part or all of the workforce may be moved over to the public sector. Government needs to understand that workforce in detail – its skills and experience – so it can plan to recruit for any gaps. But it also needs to understand the terms and conditions under which the workforce is employed, so that it can ensure that staff are moved smoothly over. This should include awareness of and planning for any TUPE requirements for staff. 254 Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, A Guide to TUPE Transfers, May 2022, www.cipd.org/uk/knowledge/guides/tupe-guide/#gref

This can help avoid any unpleasant surprises, such as higher than expected staff costs. But it can also help to ensure that the workforce has greater security, meaning they are likely to be more motivated and bought in to the transition.

Is there a plan for building support from all those involved in the service?

As a service is insourced, it is likely there will be bumps along the way, particularly with large or complex services. As new arrangements bed in, there are likely to be dips in service performance, and some benefits may only be realised in the longer term. This means it is crucial to build support for the planned change among the different groups involved in the service.

Plans for building the support of service users are also key, especially if the transition process may mean changes to the scope of the service, or how it is delivered. While part of the rationale for insourcing a service may be to improve its quality, this might not happen quickly, and users need to be given a sense of what they can expect and when. Services may also be disrupted, meaning that any changes should be clearly explained and backed up, where appropriate, with customer support. Plans to engage service users should include means for them to have their say, such as through consultations.

Other relevant groups – in particular, unions – should also be part of plans to build support for the insourced service. Unions are likely to want clarity on what will happen to the workforce, including the terms and conditions of staff’s employment, and their pension rights. There should be a clear plan for engaging relevant unions, and an awareness of what issues they are likely to raise.

The support of a minister is itself crucial in this, as it can help encourage buy-in among other relevant parties. You can help provide reassurance and encouragement among other key politicians and officials across Whitehall.

Has piloting been considered?

The Sourcing Playbook recommends that for national-level services, a pilot programme is considered when there is a “significant transformation of service delivery (including insourcing)”. This can help identify problems and make necessary adaptations before the full roll-out of a service.

Shifting a large and potentially complex service from one or more providers to government provision, potentially across many different locations, with possible changes in staffing and operational procedures, is a major undertaking. Expecting this to happen on a single day is a huge ask.

Pilot programmes should be conducted – or, at the very least, the return of services should be staggered – so that problems can be identified and mitigated.

Where to find further resources

Government guidance and advice

The Cabinet Office and Government Commercial Function issue guidance on making sourcing decisions in The Sourcing Playbook, updated annually. This includes guidance on outsourcing, insourcing and contracting. It offers advice on steps throughout the procurement process, from preparation and planning to contract implementation.

The note on ‘Principles for Ministerial involvement in commercial activity and the procurement process’, issued by the Cabinet Office and Government Commercial Function, sets out ways of maximising ministerial involvement at different stages of the procurement process.

In 2021, the government published its National Procurement Policy Statement, which sets out strategic priorities for public procurement.

Other useful guidance and advice

The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) has guidance on TUPE transfers and how best to manage them.

Research on outsourcing and procurement

The Institute for Government has undertaken research on outsourcing and procurement. This includes analysis of the scale and nature of contracting in the UK. 260 Davies N, Chan O, Cheung A, Freeguard G and Norris E, Government Procurement: The scale and nature of government contracting in the UK, Institute for Government, December 2018, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/government-procurement In 2019, the Institute brought together existing evidence on outsourcing and public services to explore where outsourcing has worked and where it needs reform. 261 Sasse T, Guerin B, Nickson S, O’Brien M, Pope T and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: What has worked and what needs reform?, Institute for Government, September 2019, accessed 7 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-outsourcing-reform This drew on earlier research on the conditions necessary for successful contracting. 262 Gash T and Panchamia N, When to Contract: Which service features affect the ease of government contracting?, Institute for Government, January 2013, accessed 2 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/when-contract

Research on insourcing

In 2020, the Institute explored insourcing, and when and how to bring public services back into public hands. 263 Sasse T, Nickson S, Britchfield C and Davies N, Government Outsourcing: When and how to bring public services back into government hands, Institute for Government, June 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/government-outsourcing-public-services-back-government-hands More specifically, we also looked in detail at the reunification of probation services 264 Davies N and Johal R, Reunification of Probation Services, Institute for Government August 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/reunification-probation-services and preparations for their transition back to the department.

- Topic

- Ministers Procurement

- Keywords

- Outsourcing Cabinet Public sector Public spending NHS

- Department

- Cabinet Office

- Series

- IfG Academy

- Publisher

- Institute for Government