Performance Tracker 2022: Cross-service analysis

This year’s Performance Tracker assesses how nine public services have coped with the effects of the pandemic.

Introduction

In 2019, the Conservative manifesto was clear about its public service priorities: increase spending and improve the performance in general practice, hospitals, police and schools. The pandemic certainly led to increased spending, with the government providing £17.8 billion more for these four services alone in 2021/22 than it did two years earlier. However, the performance of public services has declined markedly, also because of Covid.

Public services are now in a more fragile state than before the pandemic. They face higher costs due to inflation, are vulnerable to new variants of Covid, and the NHS and social care in particular expect a winter crisis following an already difficult summer.

While the Conservative leadership contest and early weeks of the Truss government have focused on tax cuts, the new prime minister is likely to be judged by the public on her response to the cost of living crisis and the progress her government has made reducing waiting times and improving access to critical public services.

This year’s Performance Tracker assesses how nine public services – general practice, hospitals, adult social care, children’s social care, neighbourhood services, schools, police, criminal courts and prisons – have coped with the effects of the pandemic, and the outlook for the remainder of this parliament. For each service we have analysed how much was spent, how the nature of demand has changed, the impact on staff and the progress of efforts to reduce backlogs or address unmet needs where applicable. It opens with a cross-service analysis considering these factors together, assessing the increased use of technology during the pandemic and identifying systemic problems across the justice, health and local services sectors that need attention from government.

The new government faces tough decisions in its upcoming ‘medium-term fiscal plan’ and the subsequent spring budget. The fiscal landscape has become more difficult since the 2021 spending review and the chancellor will need to balance funding for public services, the level of taxation and borrowing – all within the context of inflationary pressures, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, and higher wage demands that have reduced the real value of the 2021 spending decisions by the then chancellor, Rishi Sunak. The analysis in this report outlines the current state of public services and the consequences of different spending decisions.

Category |

Criteria |

|---|---|

| Performance on the eve of the pandemic vs 2009/10 322 Atkins, G, Davies N, Guerin B and others, How fit were public services for coronavirus?, Institute for Government, August 2020, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/public-services-coronavirus * | Green: Service performance (scope, quality and efficiency) on the eve of the crisis was the same or better than in 2010 |

| Amber: Service performance was somewhat worse than in 2010 | |

| Red: Service performance was much worse than in 2010 | |

|

Ongoing impact of Covid on working practices |

Green: Working practices are no longer significantly directly disrupted by Covid (due to Covid-related staff absences, building closures or enhanced infection control measures) |

| Amber: Working practices are somewhat directly disrupted by Covid | |

|

Red: Working practices are extensively directly disrupted by Covid |

|

| Current performance vs 2019/20 performance | Green: Service performance (scope, quality – including backlogs – and efficiency) is the same or better than on the eve of the pandemic |

| Amber: Service performance is somewhat worse than on the eve of the pandemic | |

|

Red: Service performance is much worse than on the eve of the pandemic |

|

| Funding adequate to return performance to 2019/20 level |

Green: Accounting for cost pressures from pay and latest inflation, it is likely that the spending review 2021 settlement provides sufficient resources to enable the service to return to 2019/20 performance by 2025 |

|

Amber: It is finely balanced or uncertain that the spending review 2021 settlement provides sufficient resources to enable the service to return to 2019/20 performance by 2025 |

|

|

Red: It is unlikely that the spending review 2021 settlement provides sufficient resources to enable the service to return to 2019/20 performance by 2025 |

|

| Workforce adequate to return performance to 2019/20 level | Green: It is likely that current government actions and plans will lead to sufficient recruitment and retention of staff to enable service to return 2019/20 performance by 2025 |

| Amber: It is finely balanced or uncertain whether current government actions and plans will lead to sufficient recruitment and retention of staff to enable service to return to 2019/20 performance by 2025 | |

| Red: It is unlikely that current government actions and plans will lead to sufficient recruitment and retention of staff to enable service to return to 2019/20 performance by 2025 |

*Where data permits, we use 2010 throughout this report as a comparison as this marks the end of 13 years of Labour governments and the beginning of 12 years of Conservative-led governments.

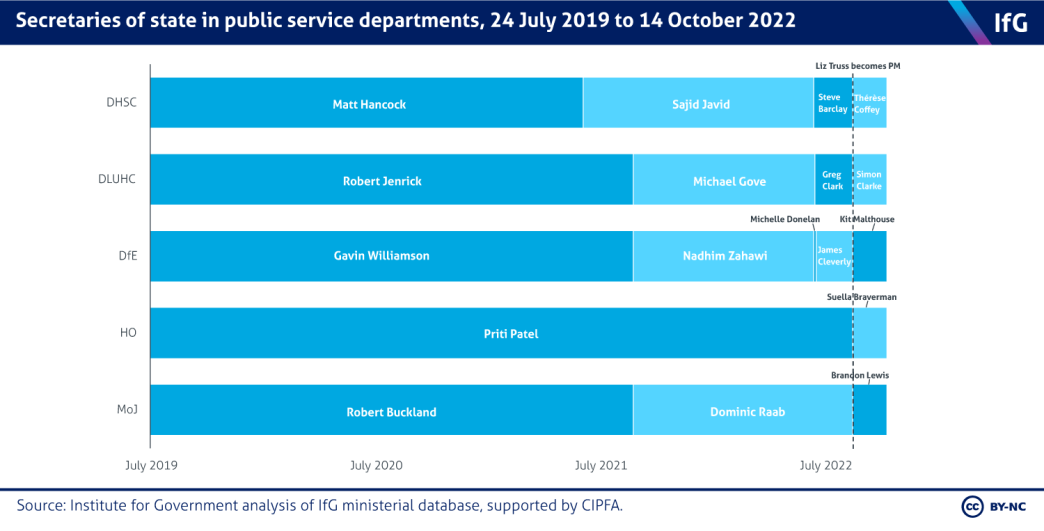

The churn in government ministers has disrupted some public service reform plans

During 2022 there has been a threefold hit on government decision making. First, the formation of a new government in September led to considerable churn in ministers, with all but four of Liz Truss’s cabinet new in post. This had been preceded by the resignation or sacking of no fewer than 30 ministers and appointment of replacements in the week before her predecessor, Boris Johnson, agreed to stand down in July. Such fast turnover leads to poor decision making. 323 Sasse T, Durrant T, Norris E and Zodgekar K, Government Reshuffles: The case for keeping ministers in post longer, Institute for Government, January 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/government-reshuffles-keeping-ministers-post-longer

Second, while acting as caretaker during the eight-week Conservative leadership election, Johnson committed to not introducing any significant reforms, further impeding decision making. 324 Donaldson K, ‘Johnson Says Major Fiscal Decisions Should Be for Next UK Leader’, Bloomberg UK, 7 July 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-07/johnson-says-major-fiscal-decisions-should-be-for-next-uk-leader

Third, though the government has not yet published concrete plans to implement the policy, the decision to reduce the civil service by 20% effectively reopened the 2021 spending review and disrupted departmental planning.

The churn at the centre of government has led to delays and changes in important policy areas. For example, the government was expected to publish a long-awaited health disparities white paper in 2022. 325 Bibby J, ‘We can’t wait for government to act on health inequalities’, The Health Foundation, 7 July 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/we-cant-wait-for-government-to-act-on-health-inequalities However, it has been reported that the new health secretary has decided against publishing the paper. 326 Campbell D, ‘Thérèse Coffey scraps promised paper on health inequality’, The Guardian, 29 September 2022, www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/sep/29/therese-coffey-scraps-promised-paper-on-health-inequality Similarly, the fate of the Schools Bill, which is yet to pass through the House of Commons, is unknown but could also be scrapped. 327 Morgan R, ‘Schools Bill under threat as Truss resets priorities’, TES magazine, 12 September 2022, www.tes.com/magazine/news/general/schools-bill-under-threat-truss-resets-priorities

Spending

Emergency Covid-support funding continued into 2021/22

Responding to Covid in 2020/21, the government significantly increased spending on public services compared to 2019/20, the last financial year prior to the pandemic, to support continuing service delivery in difficult circumstances.* For the nine services reviewed in Performance Tracker, £221.3bn was spent in 2020/21 and £222.9bn was spent in 2021/22, compared to £203.7bn in 2019/20.**

The public-facing nature of these public services meant considerable funding was required to ensure continuity of service in a Covid-secure way. Tens of billions of pounds in emergency Covid funds issued between 2020/21 and 2021/22 had been spent on the nine services covered in the report (the rest was spent on things including Test and Trace, the Bounce Back Loan Scheme and the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme or ‘furlough’).*** 328 HM Treasury, Spring Statement 2022 (CP 653), The Stationery Office, March 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, p. 17, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1062486/Spring_Statement_2022_Web_Accessible.pdf

Public services required extra spending to meet existing and additional responsibilities. For example:

- NHS trusts and foundation trusts received £2.1bn to cover lost income and £0.4bn was provided for Nightingale hospitals. 329 National Audit Office, ‘COVID-19 cost tracker’, 23 June 2022, retrieved 22 August 2022, www.nao.org.uk/overviews/covid-19-cost-tracker

- Adult social care received £5.3bn between 2020/21 and 2021/22 to provide financial assistance to care providers, facilitate discharge from hospitals, and adapt settings to make them Covid-secure. 330 Institute for Government analysis of Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, ‘Local authority COVID-19 financial impact monitoring information’, Round 20, 21 June 2020, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-authority-covid-19-financial-impact-monitoring-information

- Children’s social care received £0.8bn to cover additional accommodation and staffing costs. 331 Ibid.

- General practitioners had an additional £0.7bn of Covid-specific spending allocated to them to cover the vaccine programme and other Covid costs in 2020/21.

- Schools were given £0.5bn for free school meal vouchers and £0.6bn for digital devices to enable remote learning. 332 National Audit Office, ‘COVID-19 cost tracker’, 23 June 2022, retrieved 22 August 2022, www.nao.org.uk/overviews/covid-19-cost-tracker

Prisons were the only service with lower spending in 2021/22 than 2019/20. Day-to- day spending rose by 5.6% in 2020/21 as a number of Treasury-approved schemes were implemented to ensure the continued supply of staff. Spending is expected to have fallen almost 8% in real terms in 2021/22 as the Covid support measures came to an end.

In responding to a fast-moving situation the government, quite understandably, did not always get the most out of the extra money that was spent on services.**** For example, £2.1bn was spent on support for the adult social care market to prevent providers going out of business – while necessary to assist during uncertainty, there is no clear way to evaluate whether this money was well spent. In the NHS, little use was made of a contract with independent providers to increase spare bed capacity in the first year of the pandemic, largely due to staffing constraints. 333 Ryan S, Rowland D, McCoy D and Leys C, For Whose Benefit? NHS England’s contract with the private hospital sector in the first year of the pandemic, Centre for Health and the Public Interest, September 2021, retrieved 26 September 2022, https://chpi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/CHPI-For-Whose-Benefit_.pdf

* Not all Covid support funding went to public sector bodies but rather to support the delivery of public services. For example, in adult social care, much of the additional funding went to private providers.

** Institute for Government analysis of government spending data, supported by CIPFA. Notes: Full details on data sources are provided in the methodology chapter.

***It is not possible using the National Audit Office cost tracker to precisely identify spending on particular services. See National Audit Office, ‘COVID-19 cost tracker, (23 June 2022) retrieved 22 August 2022, www.nao.org.uk/overviews/covid-19-cost-tracker

**** The Public Accounts Committee critiqued the level of fraud and error in pandemic spending, COVID-19 cost tracker update: Thirty-eighth report of session 2021–22 (HC 640), The Stationery Office, 2022. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8934/documents/152365/default. The NAO has also identified issues with PPE contracting processes, Investigation into the management of PPE contracts, Session 2021–22, HC 1144, National Audit Office, 2022, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Investigation-into-themanagement-of-PPE-contracts.pdf, and The Bounce Back Loan Scheme: an update, Session 2021–22, HC 861, National Audit Office, 2021, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/The-Bounce-Back-Loan-Schemean-update.pdf

The 2021 spending review left some services with less money than in 2009/10

When the pandemic hit, many public services were in a precarious state following a decade of spending restraint. 334 Atkins G, Davies N, Guerin B and others, How fit were public services for coronavirus?, Institute for Government, August 2020, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/public-services-coronavirus The 2021 spending review – conducted when Rishi Sunak was chancellor in Boris Johnson’s government but which the Truss government has indicated it will stick to 335 HM Treasury, ‘Update on Growth Plan implementation’, 26 September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/news/update-on-growth-plan-implementation – led to budget increases for most services yet this has not left them on a stable financial footing.

In the criminal justice sector, spending increases for policing (since 2018/19), criminal courts (since 2017/18) and prisons (since 2016/17) have not brought these services back to real spending levels seen in 2009/10 despite the explosion of digital crimes, growth in court backlogs and prisons operating near capacity. In the NHS, hospitals and general practice spending increased over the past decade but did not keep pace with rising demand. 336 Atkins G, Davies N, Guerin B and others, Performance Tracker 2019, Institute for Government and Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy, November 2019, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/performance-tracker-2019 Overall school funding increased, but until 2021/22 was still below 2010/11 levels on a per-pupil basis. Meanwhile, local authority neighbourhood services have been cut back as budgets have been squeezed by central government grant cuts and increased spending on statutory services such as adult and children’s social care. 337 Atkins, G and Hoddinott S, Neighbourhood services under strain, Institute for Government, April 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/neighbourhood-services

Higher costs are squeezing budgets

Funding settlements for 2022/23 will struggle to cover ongoing higher public service costs despite the threat from Covid reducing. Some services have become more expensive to deliver and these costs are unlikely to fully return to pre-pandemic levels soon. The NHS is worst affected. Hospitals, for example, continue to incur costs associated with enhanced infection control measures, which may increase in response to future variants and winter case surges. Such measures also reduce the availability of beds, hampering the NHS’s ability to clear backlogs and meet acute demand. Without sustained funding to address these ongoing costs or measures to reduce demand, public service providers will face a difficult decision as to whether to let quality standards slip or to reduce the scope of service they provide.

Furthermore, the inflationary pressures affecting households are also having some impact on public services. In 2019/20 around £1.4bn was spent on electricity, gas and oil by health, education, defence, prison and probation services combined. A further

£200m was spent on fuel and £1.8bn was spent on food and catering by those same services. 338 Office for National Statistics, ‘Inflationary pressures faced by public services in England: 2022 to 2023’, 28 April 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicsectorfinance/articles/inflationarypressuresfacedbypublicservicesinengland/2022to2023 Prices for these goods and services have risen fast; even accounting for the government’s six-month intervention to cap prices for businesses and public services, energy costs will have more than doubled since early 2021. However, the impact on public services is not as severe as on households. Energy costs account for 11% of household spending among the poorest tenth of households (and 4% among the richest tenth) 339 Joyce R, Karjalainen H, Levell P and Waters T, The cost of living crunch, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 12 January 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/15905 but account for less than 1% of spending on the public services analysed by the ONS. 340 Office for National Statistics, ‘Inflationary pressures faced by public services in England: 2022 to 2023’, 28 April 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicsectorfinance/articles/inflationarypressuresfacedbypublicservicesinengland/2022to2023

Instead, the biggest cost pressures for public services are on staff, which accounts for over half of budgets in most of the services we assess. We analyse the impact of higher-than-expected pay awards in the context of the cost of living crisis below.

Demand

Covid has created substantial uncertainty about future demand for services

In some areas, service demands are higher than before the pandemic, adding pressure to already stretched systems. For example, GPs are delivering 5% more appointments than previously yet there is evidence that this is insufficient to meet demand, with patients struggling to book appointments. 341 NHS England, GP Patient Survey 2022, July 2022, www.gp-patient.co.uk/surveysandreports

In other service areas, demand fell significantly during the pandemic. In the NHS, it has been estimated that 7.6 million fewer people joined a hospital waiting list than would be expected in the first 18 months of the crisis. 342 Stoye G, Warner M and Zaranko B, ‘Where are all the missing hospital patients?’, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 7 December 2021, retrieved 26 September 2022, https://ifs.org.uk/articles/where-are-all-missing-hospital-patients In adult social care 2.4% fewer over- 65s requested to access care services between 2019/20 and 2020/21 343 NHS Digital, ‘Adult Social Care Activity and Finance Report, England – 2020-21’, Table T8, 21 October 2021, retrieved 26 September 2022, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-social-care-activity-and-finance-report/2020-21#resources and evidence suggests up to 4.5 million more people provided unpaid care during the pandemic. 344 Carers Week, Carers Week 20202 research report: The rise in the number of unpaid carers during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, 8 June 2020, retrieved 14 June, p. 4, www.carersuk.org/images/CarersWeek2020/CW_2020_Research_Report_WEB.pdf While some of these issues may have been resolved without the involvement of public services, others could have deteriorated, requiring greater support in the future – for example, some medical conditions if left untreated will require more complex interventions at a later stage.

The lower-than-expected increase in demand poses complex questions to public service providers as to whether and where this ‘missing’ demand will later materialise. To date, fewer people have been added to the elective waiting list than might have been expected, given reduced access to care during the pandemic, but it is unclear whether this is simply a consequence of bottlenecks elsewhere in the system. For example, GP referrals are still below pre-pandemic levels, despite them operating at capacity, and the NHS is unable to quantify the number of people who aren’t getting general practice appointments.*

The same is true of demand for children’s social care. Referrals fell by 7% between 2019/20 and 2020/21 but there was a 23% increase in calls to the NSPCC over the same period. 345 National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, ‘Calls to the NSPCC helpline surge during the pandemic’, NSPCC News, 29 April 2021, retrieved 24 September 2022, www.nspcc.org.uk/about-us/news-opinion/2021/nspcc-child-abuse-helpline-pandemic This suggests an increase in the number of children needing support, but this has not subsequently resulted in a surge in demand for children’s social care services – and it is uncertain whether this will be seen at a later date. However, there is evidence that the complexity of children’s needs has increased, leading to increased workloads even as caseloads stabilise. 346 Ofsted, ‘Children’s social care 2022: recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic’, 27 July 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-social-care-2022-recovering-from-the- covid-19-pandemic/childrens-social-care-2022-recovering-from-the-covid-19-pandemic#the-current-state-of-childrens-social-care

Equally, it is unclear what additional demand might arise from the 2 million people experiencing long Covid. 347 Office for National Statistics, ‘Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK’, 1 June 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid1… Given the huge pressure that public services are already under, it would be potentially catastrophic if the ‘missing’ demand noted above appeared, not least given the possible impact that the winter flu season or further upticks in Covid might have. Government needs a clearer understanding of the potential impacts of these unmet or as yet unidentified needs to better ensure an appropriate service level for users and to plan how to manage and ideally reduce these higher demand levels over the medium term.

* There are some exceptions. For example, the increased number of cancer referrals in 2021/22 broadly offset the reduction seen in 2020/21, meaning that most of the ‘missing’ demand has likely been accounted for.

Wider demographic trends will drive increased demand for most services

Services also face increased demand from demographic trends, particularly the ageing population. Interim ONS population projections show the number of people aged 85 or older will increase from 1.7 million in 2020 (2.5% of the UK population) to 3.1 million by 2045 (3.1%). 348 Office for National Statistics, ‘National population projections: 2020-based interim’, 12 January 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/bulletins/nationalpopulationprojections/2020basedinterim This will affect some services more than others. These changes have been long expected yet it remains unclear whether sufficient funding plans are in place to adequately respond.

In each service, we have projected how demand is likely to change over the current spending review period (2022/23 to 2024/25).** These projections are uncertain and will be influenced by policy and behavioural changes, but illustrate the scale of increase in demand that services are likely to face (for example, how many patients GPs will need to see and how many schoolchildren will need to be taught). We project that demand will continue to rise at least as fast as population growth in almost all services. We expect demand to grow fastest for health and adult social care (6.4%, 4.2% and 5.3% for hospitals, GPs and adult social care respectively between 2021/22 and 2024/25) as demographic pressures continue to bite; and in courts and prisons (19% and 15% respectively over the same period), with caseloads expected to increase as the Johnson government’s 2019 pledge to recruit an extra 20,000 police officers translates into more charges – though this again is uncertain.

The main exception to this is schools, where a ‘demographic dip’ means that the number of school-age children was forecast to peak in 2022 and then decline for the next decade. In theory, this could also mean reduced demand for children’s social care, but the overall number of children alone is a poor proxy for demand on these services due to the variety of factors that determine whether children require support from local authorities.

**Our approach differs by service. Full details are provided in a Methodology appendix and key details are provided in the notes below each figure.

Staffing

Some public services are struggling to fill empty posts

Staff recruitment and retention is one of the biggest problems facing public services, with the situation likely to get worse in some over the next year. In the criminal courts, a combination of stressful working conditions and low pay have contributed to falling barrister numbers. This in turn has hampered efforts to increase the number of judges, largely recruited from the ranks of barristers. In the NHS, there is currently a shortage of 12,000 hospital doctors and 50,000 nurses and midwives in England. 349 House of Commons Health and Social Care Select Committee, Workforce: recruitment, training and retention in health and social care: Third report of session 2022–23 (HC 115), The Stationery Office, 25 July 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, p. 3, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/23246/documents/171671/defyault

In adult social care, the workforce shrunk in 2021/22 due to factors such as difficult workloads during the pandemic, reductions in the pool of workers as a result of Brexit, and wages falling behind other sectors, including the NHS. In children’s social care, recent workforce surveys suggest increasing turnover may be linked to similar market conditions.

Teacher recruitment was initially boosted by the pandemic, as has been observed at other times of crisis, but the number of trainees fell over the past year. As a result, the government is now back in the position it has been in for much of the past decade, struggling to recruit and retain enough teachers.

Recruitment and retention difficulties have led to high vacancy rates. In adult social care, despite falling in the first year of the pandemic, the vacancy rate rose in 2021/22, to 10.7%. 350 Skills for Care, ‘Vacancy information – monthly tracking’, retrieved 1 August 2022, www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/publications/Topics/COVID-19/Vacancy-information-monthly-tracking.as… Likewise, vacancy rates in NHS providers initially fell but have recently risen again, with total vacancies reaching 9.7% in June 2022 – the highest level since at least June 2018, when this time series started. 351 NHS Digital, ‘NHS Vacancy Statistics England April 2015 – June 2022 Experimental Statistics’, 1 September 2022, retrieved 28 September 2022, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-vacancies-survey Unfilled posts contribute to a greater use of agency workers, who come at additional costs* and tend not to be as effective as permanent staff as they must adapt to new teams and roles.

Covid-related absences have contributed to these pressures. In prisons, higher levels of staff sickness have made it harder to safely lift pandemic restrictions, with the result that prisoners are forced to spend more time in their cells with less access to work, education and training than previously, harming both their wellbeing and prospects. The NHS too continues to suffer from many staff falling ill to Covid and other respiratory problems such as colds and flu. The overall average absence rate for NHS staff rose to 5.5% in the 12 months to April 2022, a full percentage point higher than in the 12 months to April 2021 352 NHS Digital, ‘NHS Sickness Absence Rates, January 2022 to March 2022, and Annual Summary 2009 to 2022’, 28 July, retrieved 23 September 2022, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-sickness-absence-rates/nhs-sickness-absence-rates-january-2022-to-march-2022… – equivalent to 30,000 extra staff per month absent from the workforce. These pressures will not go away and may get worse as winter approaches. Lastly, when large numbers of staff fall ill, the workload of other staff increases, which may have contributed to noted staff burn-out across health and social care settings.

GPs will need to see and how many schoolchildren will need to be taught). We project that demand will continue to rise at least as fast as population growth in almost all services. We expect demand to grow fastest for health and adult social care (6.4%, 4.2% and 5.3% for hospitals, GPs and adult social care respectively between 2021/22 and 2024/25) as demographic pressures continue to bite; and in courts and prisons (19% and 15% respectively over the same period), with caseloads expected to increase as the Johnson government’s 2019 pledge to recruit an extra 20,000 police officers translates into more charges – though this again is uncertain.

The main exception to this is schools, where a ‘demographic dip’ means that the number of school-age children was forecast to peak in 2022 and then decline for the next decade. In theory, this could also mean reduced demand for children’s social care, but the overall number of children alone is a poor proxy for demand on these services due to the variety of factors that determine whether children require support from local authorities.

* NHS England has sought to reduce the use of agency staff and agency expenditure is one of the oversight metrics included in the NHS Oversight Framework for 2022/23.

In other services, political drive has contributed to higher recruitment figures

Targeted recruitment programmes in policing and among GPs have led to staffing increases in these areas. The number of police offers is up by almost 5% in 2020/21 compared to 2019/20 due to the Johnson government’s target to add 20,000 more officers by March 2023 353 House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, The Police Uplift Programme: Fifteenth report of session 2022–23 (HC 261), The Stationery Office, 22 July 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5803/cmselect/cmpubacc/261/summary.html – though figures still stand below 2010/11 levels and recent data shows the government has fallen behind on its 2023 target. Likewise, there are also 2.7% more GPs (including trainees, which offsets the decline in fully qualified GPs) in 2021/22 compared with 2020/21, linked to a government recruitment goal – though the government again looks likely to miss its target to deliver an extra 6,000 full-time equivalent GPs by 2024.

Higher overall staff numbers mask specialist staffing gaps and lack of workforce experience

The picture beyond these increasing headline recruitment figures is more nuanced, however. In the case of the NHS, despite increasing GP staffing, recruitment is still well below demand. This is the result of a decade of underinvestment in the GP workforce that the government is now hoping to reverse with a recruitment drive as part of the NHS Long Term Plan. It’s also unclear how the increase in numbers of part-time GPs will affect total hours worked by GPs, as many part-time GPs often end up working beyond their contracted hours. Additionally, public services face specialist staffing gaps; police forces have chronic shortfalls in fraud specialists and schools face shortages of physics, languages and computing teachers, among others. These specialist shortfalls lead to reduced services and lower public service capacity.

Where staff levels are increasing, any influx in new and as such inexperienced recruits must be well managed. In policing, new entrants place an operational burden on other officers to train recruits, 354 Comptroller and Auditor General, The Police Uplift Programme, Session 2021–22, HC 1147, National Audit Office, 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, p. 8, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/The-Police-uplift-programme.pdf and the shortcomings of a young and inexperienced workforce was one of the reasons the Metropolitan Police was put under special measures in 2022. 355 ‘Met Police: Inspectorate has ‘substantial and persistent’ concerns’, BBC News, 29 June 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-61977535 In children’s social care, up to 60% of social workers in service at local authorities in 2021/22 had less than five years’ experience 356 Department for Education, ‘Children’s social work workforce’, 24 February 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-s-social-work-workforce – a concern given that a 2022 government-commissioned report stressed the importance of experienced, knowledgeable and skilled workers in the sector. 357 MacAlister J, The Independent Review of Children’s Social Care, Final report, May 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, pp. 69–70, https://childrenssocialcare.independent-review.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/The-independent-review-of-childrens-social-care-Final-report.pdf In primary care, the government is on track to meet its target to recruit an additional 26,000 direct patient care (DPC) staff by March 2024, with the aim of freeing up GP time. 358 NHS England and NHS Improvement, Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service: Additional Role Reimbursement Scheme Guidance, December 2019, p.3, www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/network-contract-des-additional-roles-reimbursement-scheme-guidance-december2019.pdf However, there is evidence that primary care networks are struggling to integrate DPC staff 359 Baird B, Lamming L, Bhatt R, Beech J and Dale V, Integrating additional roles into primary care networks, The King’s Fund, 4 March 2022, p. 9, www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-02/Integrating%20additional%20roles%20in%20general%20practice%20report%28web%29.pdf and that GP workloads have increased as they spend more time managing a large workforce. 360 Ibid., p. 18.

Similarly, in prisons, more experienced officers tend to be better at de-escalating potentially violent situations. But here, too, high levels of staff turnover mean that more than a fifth of prison officers have been in post for less than two years.

Civil service headcount cuts and strikes will exacerbate staffing problems

During the Tory leadership contest, Liz Truss’s campaign endorsed the outgoing Johnson government’s ambitions to reduce the civil service back to 2016 levels – though recent reporting suggests this target is being reviewed. 361 Pickard J, ‘Truss backtracks on cuts to 91,000 civil service jobs’, Financial Times, 6 October, retrieved 11 October, www.ft.com/content/2ec7e01c-948b-4a71-ba08-2fdd6f1c6ee9 If implemented, this would mean approximately 90,000 fewer civil servants, which would be achieved through a range of measures including a recruitment freeze. 362 Foster P and Parker G, ‘Plans to axe 91,000 UK civil servants would ‘cut public services’, Financial Times, 8 August 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.ft.com/content/95fbb2f3-51c6-449d-b79f-60b2ad170ee9 As civil servants, both prison officers and courts staff may be subject to the 20% reduction. Prisons are already struggling to operate effectively with their current workforce and it is hard to see how they can safely house the projected increase in the prison population without more prison officers. Similarly, a reduction in court staff will further hamper efforts to reduce the courts backlog.

Worsening economic conditions, alongside long-standing below-inflation pay settlements, make strikes in key public services more likely. The pay settlements announced in July 2022 were largely rejected by unions, with the exception of the Police Federation. Many health care unions – including the Royal College of Nursing, the BMA and UNISON – are balloting members on possible strikes. Teachers’ unions such as the NEU, NAHT and NASUWT are also consulting members on future action. In the justice system, criminal barristers voted for increasingly severe strike action, starting with day-long strikes in June, 363 Gregory J and Symonds T, ‘Barristers walk out of courts in strike over pay’, BBC News, 4 July 2022, retrieved 22 August 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-61946038 then alternate weeks from August, 364 Burns J, ‘Barristers to strike every other week from August with no end date’, BBC News, 4 July 2022 retrieved 22 August 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-62009941 and finally an indefinite strike that began on 5 September. 365 Walsh A and Slow O, ‘Criminal barristers in England and Wales vote to go on all-out strike’, BBC News, 22 August 2022, retrieved 22 August 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-62629776

The government faces difficult decisions. Strikes will disrupt both service delivery and efforts to reduce pandemic backlogs. It has accepted the NHS Pay Review Bodies’ recommendations 366 NHS England, ‘Letter from Julian Kelly re: 2022/23 Pay award’, PAR1863, 20 July 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/B1863-2022-23-Pay-Award.pdf to increase the NHS wage bill by approximately £2bn 367 Ibid. – around 4.6% 368 The Health Foundation, ‘Unfunded NHS staff pay increase could leave big hole in the severely stretched NHS budget’, press release, 19 July 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/news/unfunded-nhs-staff-pay-increase-could-leave-big-hole-in-severely-stretched-nhs-budget – in 2022/23 but is not funding this. As such the NHS will have to find the money from existing budgets as set in the 2021 spending review settlement. 369 HM Treasury, ‘Update on Growth Plan implementation’, 26 September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/news/update-on-growth-plan-implementation This is likely to necessitate cuts elsewhere in the service. In the criminal courts, Brandon Lewis, the new justice secretary, made a revised offer, worth £54m more, which brought the criminal barristers’ strike to and end in October. 370 Casciani D and Burns J, ‘Criminal barristers vote to end strike over pay’, BBC News, 10 October 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-63198892, retrieved 10 October 2022

Pay offers are higher than expected, eating into budget increases this year

While pay offers have been – without exception – below inflation, they have also been above what was expected when the spending review was agreed in October 2021. Pay review bodies have now reported and the government has responded, in most cases accepting the bodies’ recommendations. For 2022/23, pay increases in our nine services range from 3% in courts to 8.5% in prisons. Some workers in these services have been awarded larger increases than this – for example, early-career teachers – though these are offset by smaller increases elsewhere. Table 2 lays out the average awards.

Across our public services we estimate that the total cost of pay awards in 2022/23 will be £3.3bn more than the 2–3% increase anticipated by the spending review. Even this understates the effect of pay pressure in the public sector because many local government services are contracted out and suppliers will be experiencing pay pressures that they will pass on to local authorities.

Despite this, in most services pay is still increasing less quickly than private sector wages, which the Bank of England expects will increase by 5.25% in 2022. This means that despite pay increases being beyond what was expected, they could nonetheless have a negative impact on retention as other options in the private sector look relatively more attractive. Increasing pay in line with private sector wages would cost an additional £440m.

The pressures on budgets are reduced a little by the reversal of the health and social care levy, announced in the former chancellor’s September ‘mini-budget’, as the levy imposed costs on public services as employers. But the effect of higher basic pay increases is much larger, as the levy was only a cost to employers of 1.25% of salaries above the tax threshold.

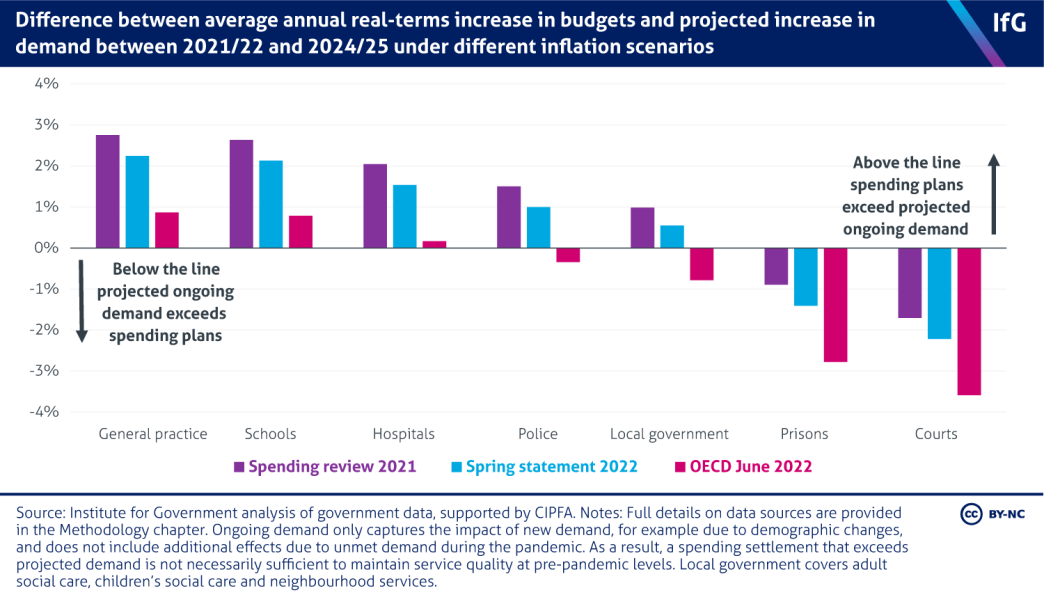

Higher inflation in the economy as a whole, on top of higher pay awards, means that what was originally a very generous spending review settlement in October 2021 now looks much less so. In October 2021, spending was expected to increase by over 7.6% on average across our services in 2022/23 in real terms. Taking into account the latest projections for economy-wide inflation from the OECD, we now project that the spending power of our services will in fact increase by only 4.1%.

This is still a substantial real-terms increase for one year, but may store up problems for future years. Most of the spending increases planned in the 2021 spending review settlement were front-loaded, with big increases in 2022/23 but barely any in the subsequent two years. Again using OECD projections, we predict that on average our services will see budgets increase by 1.5% per year over the spending review period as a whole compared with a planned 3.4%. Even this could understate the costs facing public services as energy prices – largely excluded from calculations of the GDP deflator – will still affect public service providers even though a relatively small share of their budgets is spent on energy.

Current spending settlements are now unlikely to be sufficient

As a result of these cost increases, the 2021 spending review settlement is now unlikely to be sufficient to meet growing demands and deal with the aftermath of the pandemic in most services. Spending per pupil will increase in schools, but not by enough to recover lost learning since 2020. Hospital and general practice spending may just be sufficient to meet new demographic demand but not to address all of the ‘missing’ demand, should it materialise, or to enable a big enough increase in activity to unwind Covid backlogs.

In combination, the spending settlement for local government is no longer sufficient to meet demand in adult social care, children’s social care and neighbourhood services. It is the former that accounts for the highest share of the budget and where demand is increasing most quickly. Even this analysis understates the squeeze on local authorities due to the impact that the extra demands on adult social care services, due to government reforms, will have on overall local authority finances. And the government’s projections of local government spending power are predicated on council tax increases of 3% per year, which may prove politically unpopular and so difficult to deliver given the squeeze on household incomes.*

In prisons and courts, new demand is set to exceed even generous spending settlements. Even in the police, budget increases over the next few years will not exceed demand, but this does mask big increases in the budget since 2019/20, which means this is the only service where we judge that spending is sufficient to return performance to pre-pandemic levels.

* This policy is discussed in more detail in the Adult social care chapter.

Backlogs

Many public services are still dealing with backlogs that grew during the pandemic. The small increase in spending power outlined above will not be enough to substantially reduce these backlogs and so return performance to pre-pandemic levels.

Backlogs are most apparent in hospitals and courts, while the lost learning in schools also constitutes a ‘backlog’ of teaching that will need to be compensated for if the affected cohorts of students are to reach expected attainment levels. In other services, such as children’s social care, there was temporarily lower activity during 2020 and early 2021, which could materialise into extra demand going forwards, but the data so far does not show that this has happened.

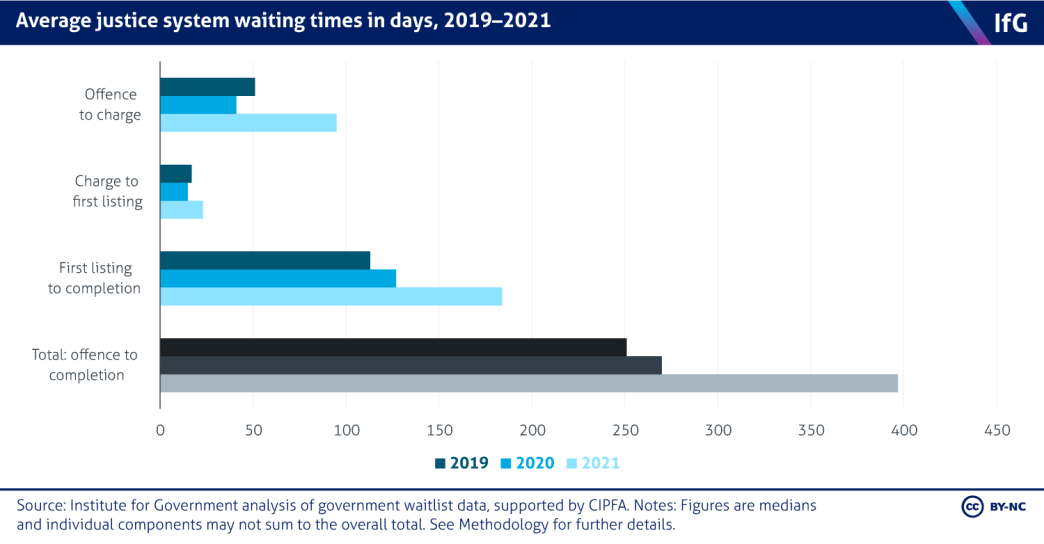

Longer waiting times are a problem in and of themselves because people cannot access services quickly. But in many cases longer waiting times will also lead to worse outcomes. For example, there has been a continued decrease in the share of urgent cancer referrals seen within two months, meaning some patients’ condition may have worsened by the time they are treated. In the justice system, too, longer waiting times mean that many victims may not support a prosecution when a resolution could be years away and, when cases are eventually heard, recollections of events many years before might be unreliable, making it harder for justice to be served. Waiting times have increased both before the case even reaches court (the time between the offence and a charge) and – more substantially – once a case is in the court system.

Backlogs were growing before the pandemic but were badly exacerbated by it

In both hospitals and courts, measured backlogs are at historically high levels. Waiting lists for elective treatments stood at 6.8 million people as of July 2022, the highest on record, while approximately 425,000 people were waiting six weeks or more for diagnostic tests – down from a peak of almost 573,000 in May 2020 but much higher than the 86,000 in March 2020. In the crown court, where the most serious cases are heard, the backlog stood at 59,700 in June 2022, slightly below the peak of more than 60,000 in June 2021 but higher than at any point since at least 2000.

These backlogs are not just an effect of the pandemic. In both services, backlogs were already increasing before this. Waiting lists for elective procedures rose from 2.3 million in February 2010 to 4.4 million in February 2020. In the same time period, the number of people waiting more than six weeks for a diagnostic test increased from 4,000 to 30,000. Meanwhile the crown court backlog increased from a low of 33,000 in March 2019 to almost 40,000 at the onset of the pandemic. But the scale of disruption wrought by the pandemic led to a serious worsening of these backlogs. Almost all elective procedures and jury trials were put on hold for months. Crown court backlogs increased by 43.2% between March 2020 and December 2021 while the NHS elective waiting list increased 54.6% over the same period.

The true size of backlogs is not captured in the headline statistics

Even the enormous backlogs currently on record do not capture the full scale of the problem. The best measure we have for ‘backlogs’ in the health system is published waiting lists. But in practice there will be others in need of treatment who are not yet on the waiting list, perhaps because they have not yet been referred by their GP or are struggling to get an appointment in the first place.

GP referrals fell substantially during the pandemic. This is partly because the NHS made a concerted effort to reduce non-urgent elective care in hospitals at the start of the pandemic, which resulted in 5.3 million (or 32%) fewer completed elective pathways in 2020/21 compared to 2019/20. It also extended the rollout of ‘advice and guidance’ (A&G) – an innovation that has had the effect of lowering the referral rate from primary to secondary care. Finally, several interviewees told us that hospitals are rejecting referrals at a greater rate than before the pandemic.

This may partly explain why, though long, waiting lists have not increased by more. In the case of the elective backlog, the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimated that 7.6 million fewer people joined a waiting list for hospital care during the pandemic than they would have expected. 371 Stoye G, Warner M and Zaranko B, ‘Where are all the missing hospital patients?’, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 7 December 2021, retrieved 26 September 2022, https://ifs.org.uk/articles/where-are-all-missing-hospital-patients While some of those people may no longer require care, it is likely that others will come forward and that the flow on to waiting lists has merely been slowed by the difficulty of accessing health services, rather than cut down as a result of falling demand. As a result, the ‘true’ increase in the number of people waiting for treatment is likely to be higher still than the 2 million person increase the elective waiting lists suggest.

In the crown court, every outstanding case is recorded in the same way whether or not it is an appeal, a decision for sentencing, a case that requires a jury trial or a case that will not. But some cases will take much more time to process than others. Jury trials (required only when defendants plead not guilty) account for less than 20% of all cases in the crown court but take up over 75% of court time. During the pandemic, it was jury trials that were most badly affected because they require so many people to be in the courtroom and they could not be heard online. This means that the backlog now disproportionately contains these lengthier cases, which will take longer to process. We calculate that, after adjusting for the composition of the backlog, on a like-for-like basis the backlog has effectively doubled to more than 80,000 cases, and barely begun to fall.

While the headline statistics for these backlogs may not capture the true scale of unmet need, they do at least provide a starting point. In other services, and schools in particular, there is no regular gauge on progress towards recovering and reversing the impacts of lost provision during the pandemic. A series of studies has shown conclusively that disruption to in-person teaching meant pupils fell behind in their learning, and that this was especially true for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. 372 Education Endowment Foundation, The Impact of COVID-19 on Learning: A review of the evidence, May 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/documents/guidance-for-teachers/covid-19/Impact_of_Covid_on_Learning.pdf?v=1652815530 The decline in Key Stage 2 (age 11) performance in 2022 gives one measure of the impact of lost learning, but a lack of consistent external assessments makes it much harder to track the impact on older pupils.

The government’s ambitions are unlikely to be met given the resources available…

The government has set out plans to tackle backlogs over the spending review period. But in each case it will be difficult to achieve these plans given current resourcing plans, even where they are relatively unambitious.

The government’s approach to the crown court falls squarely in the ‘unambitious’ category. Its stated ambition is to reduce the backlog to 53,000 cases by November 2024. This would mean that the backlog would have fallen by only 7,000 cases from its peak and would still be 14,000 cases above pre-Covid levels. Before the announcement of barrister strikes, the government was on track to meet this with room to spare – the backlog fell by 2,000 cases in the six months to March 2022. But even then the number of cases outstanding fell only because the inflow of cases into courts (which depend on police activity) continues to fall below expectations. The courts are still less efficient than they were before the pandemic, with many trials being rearranged due to Covid-related absences. So, if case receipts pick up as expected, the courts will struggle to make any inroads into the backlog at all.

In hospitals, the NHS very nearly met the first, though least ambitious, of its three targets in the backlog delivery plan: eliminating waits of more than two years by July 2022. But its subsequent targets – eliminating 18-month and one-year waits by April 2023 and May 2025 respectively – will be much harder to meet and crucially rely on hospitals being able to operate at 130% of pre-pandemic activity levels, despite currently operating at roughly 95%. Given that hospitals still have some enhanced infection control measures in place, reducing their efficiency, this will be especially difficult to achieve.

On schools, while the ‘backlog’ is less easily quantified the government has certainly not shown much ambition in its funding, committing only £5bn to education catch-up between 2020/21 and 2023/24. This is one third of the £15bn that the government’s education recovery commissioner recommended in 2021, suggesting the current programme is unlikely to be sufficient to reverse the detrimental impact of the pandemic. Furthermore, the National Tutoring Programme, the single largest programme dedicated to education catch-up, got off to a rocky start. In March 2022, funding was transferred from two strands of the scheme administered by recruiting firm Randstad, to a strand under which schools are able to source their own tutors.

… and extra funding alone will not be sufficient to clear all backlogs

One of the reasons backlogs are so difficult to tackle – and so the government’s plans are so difficult to meet – is that they are not problems that can be solved with one-off funding injections. Instead, other problems mean that there is only so much difference that short-term extra spending would make. For example, in the courts, the Ministry of Justice has once again provided funding for ‘unlimited sitting days’.* But limits elsewhere – principally a shortage of judges and barristers – mean that despite a supposed blank cheque the number of cases dealt with this financial year is unlikely to be much higher than last.

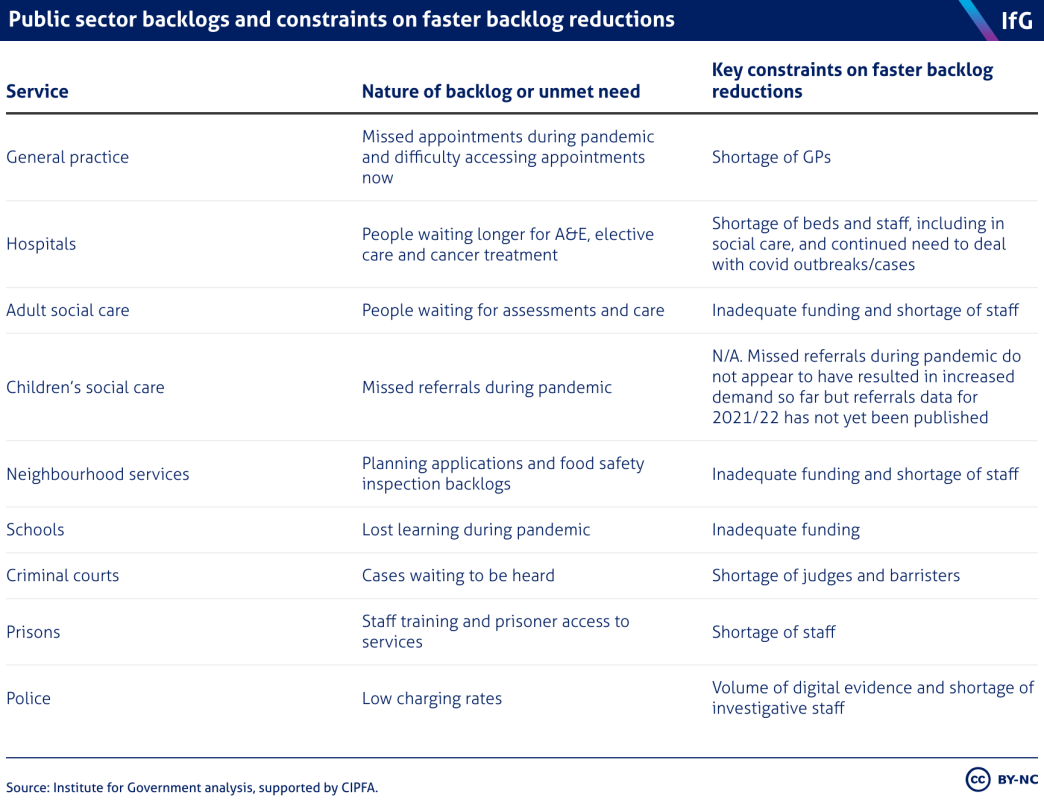

As Table 3 highlights, similar workforce constraints apply in other services with backlogs. These are the types of restrictions that can be lifted in the longer term – for example, by training more doctors or substantially increasing pay – but not ones that can be solved overnight.

* Days in which there is no financial restriction on the number of court sittings that can occur.

Maintenance backlogs are growing, further limiting the capacity of services

A sizeable maintenance backlog totalling almost £23.7bn has accumulated across the NHS, schools, courts and prisons. But deferring necessary upkeep costs to the future is a false economy as smaller, earlier fixes are cheaper than the cost of bringing dilapidated assets back to standard.

The latest assessment of the schools estate, published in 2021, identified an average of £311,000 repairs for each primary school and £1.6m for each secondary school – totalling £11.2bn. 373 Department for Education, Condition of School Buildings Survey: Key findings, May 2021, retrieved 23 September 2022, p. 26, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/989912/Condition_of_School_Buildings_Survey_CDC1_-_ke… Similarly, in 2021/22 the NHS hospital estate faced a maintenance backlog standing of £10.2bn, some 8.5% higher than a year earlier. 374 NHS Digital, ‘Estates Returns Information Collection – Summary page and dataset for ERIC 2021/22’, 13 October 2022, retrieved 13 October 2022, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/estates-returns-information-collection/england-2021-22 This followed substantial cuts to NHS capital spending from 2010 onwards. 375 Atkins, G, Davies N, Guerin B and others, How fit were public services for coronavirus?, Institute for Government, August 2020, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/public-services-coronavirus A poorly maintained estate is detrimental to hospital productivity – central heating or air conditioning failures might force hospitals to close wards, or faulty equipment may fail during procedures.

This problem is not restricted to schools and hospitals. In prisons, the backlog of highest priority major capital works is currently estimated to be around £1.3bn. These include projects to address significant health and safety or fire safety risks, and/or critical risk to capacity. The backlog has been increasing by around £225m per annum in recent years, from £900m in 2019/20. 376 Figures provided by the Ministry of Justice. In courts, the former chief executive of HMCTS estimated in March 2022 that the courts maintenance backlog stood at £1bn but also cautioned that improvements to courtrooms would see them taken out of action, potentially increasing the backlog of cases. 377 House of Commons Justice Committee, Court Capacity: Sixth report of session 2021–22 (HC 69), The Stationery Office, 27 April 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/21999/documents/163783/default/

If efforts are not made to bring these assets back to good working standards, services may deteriorate. Teachers, doctors, nurses and other public sector workers require adequate space and equipment to carry out their roles and a dilapidated estate may bake inefficiencies into the system at a time when productivity gains are required to tackle backlogs and unmet need. The Treasury and spending departments should carefully consider these risks if they plan to deplete already tight capital budgets, as happened between 2010 and 2020. 378 Atkins G, Pope T and Tetlow G, Capital Investment: Why governments fail to meet their spending plans, Institute for Government, February 2020, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/capital-investment-governments-spending-plans

Performance

The performance of most public services has declined since the start of the pandemic

Unsurprisingly, given the disruption caused by Covid, the scope or quality of all nine services that we assess has deteriorated over the past two years. But this cannot be put down solely to the pandemic and in most cases continued the downward trend seen since 2010.

The worst affected services are hospitals, criminal courts and prisons. All three have been unable to conduct business as usual for large periods of the pandemic, leading to substantial growth in backlogs and waiting times. The real size of the crown court backlog, taking into account the complexity of cases, has barely started to fall, while the elective treatment backlog is likely to continue growing for years to come. This means the public must wait far longer to access care or see justice served. Meanwhile, large parts of the prison estate remain heavily restricted, with prisoners spending longer in their cells with less access to rehabilitative activity.

Key performance measures for other services have also declined. The rate and number of police charges have continued to fall, while polling data shows public satisfaction and confidence in police has been severely dented by a series of high-profile scandals. Similarly, patient surveys show that many are finding it increasingly difficult to make GP appointments. In 2022, only 56.2% rated their experience of making an appointment as good or better, down from over 70% the previous year. Overall satisfaction with general practice fell from 83% to 72.4% over the same period.

The same trend can be seen in local authority delivered services, with many adult social care and neighbourhood services shrinking in scope or reducing levels of support. Meanwhile, schools have not been provided with sufficient resources to enable pupils to catch up on learning lost during the pandemic.

All this would have been more manageable had services been in good shape on the eve of the crisis. However, the decade of spending restraint from 2010 onwards had already resulted in longer waiting times, reduced access, rising public dissatisfaction, missed targets and other signs of diminishing standards. Prisons, general practice and hospitals had seen the most dramatic decline in performance over this period, but all services, with the sole exception of schools, entered the crisis performing worse than a decade previously. 379 Atkins, G, Davies N, Guerin B and others, How fit were public services for coronavirus?, Institute for Government, August 2020, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/public-services-coronavirus

Added to the slow pace of recovery from Covid, public services are poorly placed to weather future disruptions, be those heatwaves, winter flu, future Covid outbreaks or other emergencies. In particular, the NHS has struggled throughout 2022, even during the normally quieter summer months, with the elective backlog, A&E waits and ambulance response times all at record levels. The winter is likely to be even worse due to higher levels of flu and a possible Covid resurgence.

These problems will be exacerbated by the cost of living crisis. The NHS Confederation has issued a warning that high energy prices could create a “public health emergency” as people cut back on food and heating, putting further pressure on health and care services. 380 NHS Confederation, ‘NHS leaders make ‘unprecedented move’ urging to act now on rising energy costs or risk public health emergency’, press release, 19 August 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.nhsconfed.org/news/nhs-leaders-make-unprecedented-move-urging-government-act-now-rising-energy-costs-or-risk And the former chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, has previously highlighted that “the frequency and severity of health problems like flu, heart attacks and depression… have all been linked to cold homes”. 381 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Sustainable Warmth: Protecting vulnerable households in England, CP 391, The Stationery Office, February 2021, retrieved 23 September 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/960200/CCS207_ CCS0221018682-001_CP_391_Sustainable_Warmth_Print.pdf Government support to cut energy bills might reduce some of these impacts but energy bills will still be much higher than they were even a year ago and as prices more broadly exceed wage increases households will be looking for ways to save money.

Even without these problems, it is unlikely that any service, other than the police and possibly children’s social care, will perform better in 2025 than they did pre-crisis, and there is even less chance that they will reach the performance high watermark of 2010.

Limited data makes it harder to assess performance

The trend of worsening performance across most services is clear but the absence of critical data makes it harder to get the full picture. For example, the NHS does not collect information on the number of people who are unable to book GP appointments, making it impossible to accurately gauge the level of unmet need and the extent to which ‘missing’ demand from the pandemic is likely to reappear.

Similarly, the suspension of many inspection activities during the pandemic means that there is less publicly available information than usual on the performance of public services. From March 2020 to April 2021, the Care Quality Commission – the inspection body overseeing the NHS and adult social care – paused routine inspections and focused on areas of serious risk to the public. 382 Care Quality Commission, ‘Update on CQC’s regulatory approach’, 24 March 2021, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.cqc.org.uk/news/stories/update-cqcs-regulatory-approach It later adopted a more risk-based approach in early 2021 before in December 2021 affirming it had no intention of returning to its regular inspection regime due to winter pressures and the Omicron variant. 383 Ibid. , 384 Care Quality Commission, ‘Update from our Chief Inspectors on our regulatory approach’, 10 December 2021, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/how-we-inspect-regulate/update-our-chief-inspectors-our-regulatory-approach-10 Similarly, Ofsted suspended routine inspections of schools and children’s social care services from March 2020, only resuming a full programme of inspections from September 2021 for schools and from April 2021 for children’s homes. 385 Department for Education and Williamson G, ‘Routine Ofsted inspections suspended in response to coronavirus’, press release, 17 March 2020, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/news/routine-ofsted-inspections-suspended-in-response-to-coronavirus , 386 Ofsted, ‘School inspection results show positive picture despite pressures of pandemic’, press release, 13 December 2021, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/news/school-inspection-results-show-positive-picture-despite-pressures-of-pandemic; www.naht.org.uk/Advice-Support/Topics/ Coronavirus-the-latest-information-and-resources-for-school-leaders/ArtMID/764/ArticleID/137/Ofsted-inspections-from-May-2021-guidance-for-members , 387 Ofsted, ‘Main findings: Local authority and children’s homes in England inspections and outcomes – autumn 2021’, 25 November 2021, retrieved September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/local-authority-and-childrens-homes-in-england-inspections-and-outcomes-autumn-2021/main-findings-local-authority-an…

These were pragmatic decisions. It was important to design an appropriate, proportionate and safe inspection regime during the worst of the health crisis – but the result is that we lack a comprehensive picture of quality across all health care, adult social care, children’s social care and education settings. As inspection regimes return to normal we will gain an increasingly detailed picture of any decline in services. Though with CQC inspections changing due to the 2022 Health and Care Act, with new responsibilities across integrated care systems, the new normal may be different to pre-pandemic.

Fewer cases than anticipated are progressing through the criminal justice system

Even before the pandemic, the criminal justice system – which starts with the police and ends with prisons and probation – was due to undergo substantial change and pressures during the early 2020s. From 2014 onwards, the system was characterised by declining caseloads: fewer police charges, which in turn meant fewer court cases and a slower inflow into prisons. But this trend was expected to reverse following the government’s announcement that it would increase police officer numbers by 20,000 by 2023, returning the total to 2010 levels. The Institute for Government, among others, projected that this would lead to more cases being charged by the police, which in turn would lead to more demand for the criminal courts and, by extension, prisons. Both the 2019 spending round and the 2020 spending review included additional resources to help criminal courts and the Crown Prosecution Service manage this.

However, charging rates are yet to increase. The changing nature of crime and expansion of police responsibilities during the pandemic probably contributed to a 3.7% fall in the number of charges between 2019/20 and 2020/21 388 Home Office, ‘Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2020 to 2021’, Table A.3, 22 July 2021, retrieved August 2022, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/crime-outcomes-in-england-and-wales-2020-to-2021 – but charges fell again in 2021/22, even as policing activity returned to normal patterns. 389 Home Office, ‘Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2021 to 2022’, Table A.3, 21 July 2022, retrieved August 2022, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/crime-outcomes-in-england-and-wales-2021-to-2022

There are several possible explanations for this, each of which would have different implications for demand in courts and prisons going forwards. One is that investigations are under way but simply haven’t got to court yet. If that is so, a low number of charges could be a one-year blip.

Others have pointed to where new police officers are deployed. New recruits tend to be placed in visible, front-line roles rather than filling the gap in, say, detectives that has been identified by the Police Federation, among others. While new officers can arrest people within a matter of weeks – as much of the training they receive is ‘on the job’ and a lot of routine crime is investigated by uniformed officers – they also require effective support and mentoring to learn the evidence standards needed for successful prosecutions. In short, more arrests on the street does not always mean more charges, and HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire Services recently found the relative inexperience of new officers was contributing towards low charge rates even for volume crimes such as theft, robbery and burglary. 390 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, The police response to burglary, robbery and other acquisitive crime – Finding time for crime, 11 August 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/publication-html/police-response-to-burglary-robbery-and-other-acquisitive-crime

There has also been criticism from parliament about the way new officers have been allocated across forces – including the use of an outdated allocation formula, meaning some officers are being assigned to areas they aren’t needed. 391 House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, The Police Uplift Programme: Fifteenth report of session 2022–23 (HC 261), The Stationery Office, 22 July 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, p. 14, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/23202/documents/169519/default If this is the predominant reason for low charge rates, we should expect the trend of lower-than- expected charging rates to continue.

Finally, interviewees pointed to the growing complexity of crime as a countervailing force that means more police investigative time is not translating into more prosecutions. There are two facets to this trend. First, interviewees pointed to growing amounts of digital evidence – a trend we identified in 2020 as a big driver of declining charge rates. 392 Davies N, Guerin B and Pope T, The criminal justice system, Institute for Government, April 2020, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/criminal-justice-system Second, police have been more focused on certain crimes – especially sexual assault – that tend to be more complex and take longer to investigate and which have led to very few successful prosecutions in the last few years.

If extra police officers do – as expected – reverse the decline in charges, both the courts and prisons will face substantial demand pressures. This is reflected in our demand projections for both services above. This will be difficult for the courts. As noted above, in the next couple of years the courts have little capacity to increase case processing because they are constrained by the availability of judges and barristers.

And in 2021/22 there was evidence that the courts are still not operating as efficiently as before the pandemic, further limiting capacity.* It then follows that, if courts could increase their throughput, prisons would also struggle. Before March 2020, prisons were almost at capacity but as the number of trials fell during the pandemic, so did the number of prisoners. The number of prisoners has now crept up over 80,000 again and the current estimate of usable operational prison capacity is just 82,899.

This is a long way short of the more than 95,000 places that the MoJ projects, based on growing police and court activity, will be needed by 2025. This gap could be bridged by the Johnson government’s plans to build 20,000 additional prison places by the mid- 2020s (of which around 3,100 are ready) but governments have struggled consistently in the past decade to meet similar aims.

* For example, the vacation rate has increased in 2021/22. For further details see the Criminal courts chapter.

Fewer patients than needed are passing through the health and care system

Like criminal justice, health and care is a system with interdependent services. Although hospitals receive the lion’s share of funding (and political attention) it will not be possible to reduce waiting times for A&E, elective care or cancer treatment without sufficient community care and adult social care capacity to support this. And it will be harder for GPs to manage their caseloads unless they can refer patients to hospitals in a timely manner. Unfortunately, the system is currently performing worse than the sum of its parts, with problems in one service increasing demand in others.

It is hard to quantify demand for general practice because, as noted above, there is no data collected on the number of people who are unable to book appointments. However, in addition to underlying demand for primary care and that generated by Covid-related conditions, GPs are facing pressures created by the failure of a range of public services to support patients at the first time of asking or in the most appropriate setting. For instance, we heard that GPs now spend more time supporting patients with long-term conditions who might otherwise have been treated in community, secondary or adult social care.

What is certain is that GPs are referring fewer patients to hospitals both in comparison with pre-pandemic referral rates and in absolute terms. There are a number of reasons for this, the most important of which is NHS England guidance for GPs to liaise with secondary care colleagues to gain advice on whether a referral is the best course of action. However, even where referrals are made, hospitals are now more likely to reject them, 393 British Medical Association, NHS backlog data analysis, last updated 8 September 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/pressures/nhs-backlog-data-analysis , 394 Institute for Government interview. pushing them to other parts of the system, including primary care, community care and adult social care. While these measures may help to reduce demand on hospitals, it will also increase the workload of GPs and other forms of community care, limiting their ability to meet unmet need in their areas.

In hospitals, problems are arising from all directions. At the height of the pandemic the number of diagnostic tests, outpatient appointments and referral-to-treatment times dropped substantially. Data from July 2022 shows activity for each has increased but is yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.

NHS capacity to accommodate more admissions is being limited by a high bed occupancy rate. A major contributory factor towards this is the 18.7% decline in the number of general and acute overnight beds from 274.4 beds per 100,000 people in 2010/11 to 223 per 100,000 at the end of 2021. High occupancy rates are also due to delays discharging patients. Thousands of patients a day who meet the criteria for discharge are unable to leave due to problems within the hospital system and insufficient social care capacity. This is driven by a number of factors: a lack of social workers employed by local authorities who carry out assessments for care, shortfalls in care worker staffing levels, and insufficient community care.

With 50,000 fewer workers employed in the adult social care workforce in 2021/22, the sector faces challenges to recruit and retain staff – a problem that is likely to increase as staff are attracted to better paid work elsewhere, including in the NHS. The government recognised the problem with delayed discharges in Our plan for patients 395 Department of Health and Social Care, Our plan for patients, 22 September 2022, retrieved 28 September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/our-plan-for-patients/our-plan-for-patients but the £500m fund announced is not new money and given its limits – both in terms of time and funding – is unlikely to make a long-term difference to the problem of delayed discharge.

While many patients who could be discharged are not, others are discharged earlier than they otherwise would have been due to bed and staff shortages, increasing demand on adult social care providers. According to the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, these people “are sicker, have a high level of need than they would have had prior to Covid-19, meaning additional and more intensive support is required in the community and via local authority funded adult social care”. 396 Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, Spring Budget Survey 2022, 19 July 2022, retrieved 23 September 2022, www.adass.org.uk/media/9385/adass-spring-budget-survey-2022-pdf-final-no-embargo.pdf

Concerningly, there are also signs of a backlog in social care demand with more than 294,449 people awaiting assessment by social services as of April 2022, 397 Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, ADASS Survey – Adult social care: people waiting for assessments, care or reviews, 4 August 2022, retrieved 28 September 2022, p. 3, www.adass.org.uk/media/9377/adass-survey-asc-people-waiting-for-assessments-care-or-reviews-publication.pdf up from approximately 70,000 people in September 2021. 398 Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, Waiting for Care and Support, 13 May 2022, retrieved 25 May 2022, p. 5, www.adass.org.uk/media/9215/adass-survey-waiting-for-care-support-may-2022-final.pdf Delayed assessments may feed back into NHS pressures if a lack of proper care packages and adjustments lead to more serious medical problems.

Increasing social care costs have put pressure on local neighbourhood service budgets

A decade of cuts to grant funding by central government forced councils to prioritise spending on some services to the detriment of others. 399 Atkins, G and Hoddinott S, Neighbourhood services under strain, Institute for Government, April 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/neighbourhood-services Between 2009/10 and 2019/20 there was a 63% reduction in local authority grants (in 2019/20 prices and factoring in business rates as a grant). 400 Ibid., p. 6. In response councils increased revenues from other sources including sales, fees and charges, and the ‘adult social care precept’ (introduced in 2015 to allow local authorities to raise additional council taxes to finance adult social care), but these have not alleviated pressure on council budgets. 401 Ibid.