Common Fisheries Policy

The UK receives €243.1m in subsidies between 2014 and 2020 under the CFP. After Brexit, those subsidies will end.

What is the Common Fisheries Policy?

The Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) is the mechanism and set of rules through which European fishing fleets and fish stocks are managed. It began in 1970 and was most recently reformed in 2014.

The CFP applies to all EU member states, but only 22 of the EU27 are coastal states. It gives all European fishing fleets equal access to EU waters to create fair competition. It aims to ensure that European fishing is sustainable, balancing the desire to maximise catches with conserving fish stocks.

What does the CFP actually do?

The CFP has four main policy areas:

- Fisheries management – ensuring the long-term viability of fish stocks like cod, tuna, and prawns in EU waters.

- International policy and co-operation – working with non-EU countries and international organisations to manage shared fisheries, including Norway, Iceland, Morocco and Cabo Verde.

- Market and trade policy – creating fair competition in the market and setting standards on seafood products sold within the EU to protect consumers, such as requirements for clear product labels.

- Funding – money to support fishermen transitioning to more sustainable fishing and assist coastal communities in diversifying their economies. The UK has chosen to spend €19.3m of its EU funding on improving sustainability in the sector during 2014–20.

How does the CFP work?

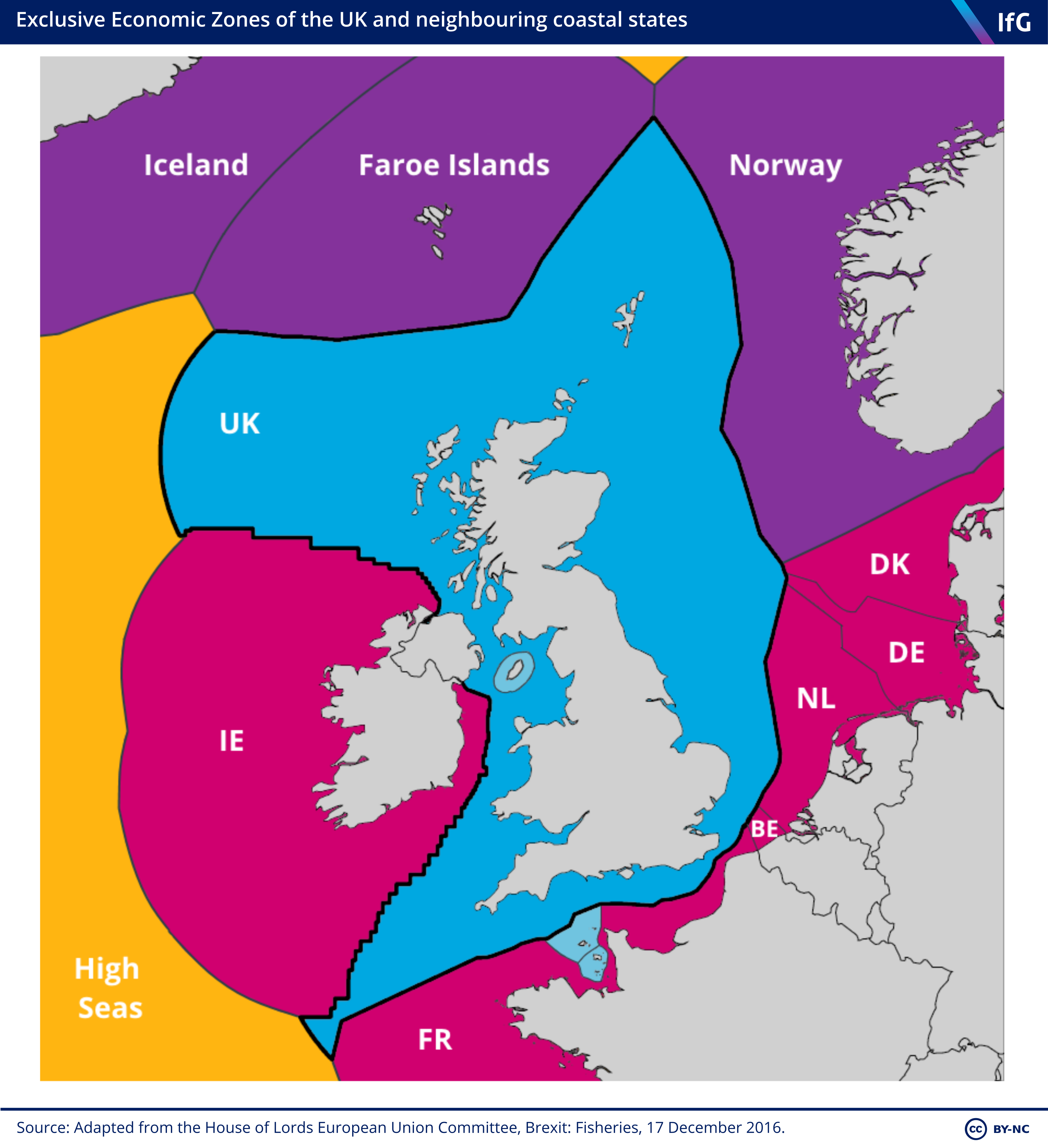

Each coastal state has the right to manage natural resources in its Exclusive Economic Zone, but under the CFP, the fishing area of all EU states is considered one zone (see map above). The CFP uses a mixture of input and output measures to control and manage fisheries sustainably.

Input controls include:

- controlling which vessels can access different areas of the sea

- limiting the length of time at sea or number of vessels in a fleet able to go out to sea at any one time

- regulating the gears and methods fishermen use.

Output controls are limits on the amount of fish that can be caught. The quotas set on each type of fish are known as total allowable catches (TAC).

How are fishing quotas set?

Quotas are set annually by the Agriculture and Fisheries Council on the basis of advice from international and EU bodies like the International Council on the Exploration of the Sea and the Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries. Quotas set for commercial fish stock must comply with the CFP’s goal of meeting sustainability targets, known as maximum sustainable yield, by 2020.

Once the overall EU quotas are agreed, member states are given a percentage on the basis of relative stability, which includes several factors such as historical catch data and the needs of coastal communities which are particularly dependent on fisheries.

Each fishing vessel receives individual quotas. For stocks that are shared with non-EU countries, quotas are agreed bilaterally or multilaterally, often through regional fisheries management organisations, such as the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC).

Why do some in the UK have issues with the CFP?

The CFP has faced harsh criticism in the past, with the Scottish government calling it “the EU’s most unpopular and discredited policy”. The policy has been accused of being an overly centralised, top-down approach from Brussels to managing fisheries.

Before January 2015, discarding undersized fish or fish that were over a vessel’s quota was a particularly contentious point of the CFP, but this has now been replaced with an obligation to land all fish caught in an attempt to eradicate waste and encourage more targeted fishing.

Others have criticised the equal access of EU vessels to UK waters. They argue that as the UK has a relatively large fishing zone compared to many of its continental European neighbours, EU fishermen benefit more from access to UK waters, a criticism supported by the University of the Highlands and Islands.

Meanwhile, environmental groups have argued that the CFP does not go far enough in protecting fish stocks. The New Economics Foundation found that quotas were regularly set above scientific advice between 2001 and 2016, and criticised the opaque nature of quota negotiations in the Agriculture and Fisheries Council.

After Brexit, what happens to the UK fishing industry?

The government has introduced the Fisheries Bill to provide a framework for fisheries policy after Brexit and once the UK has left the Common Fisheries Policy. It allows the UK to operate as an independent coastal state under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 and revokes the EU legislation which currently sets UK fishing opportunities, giving that power to the secretary of state (following consultation with the devolved administrations).

The bill also contains new fisheries objectives and places a requirement for the governments in the UK to publish joint fisheries statements setting out their chosen policies to achieve those objectives.

Can the UK do whatever it wants with fisheries policy after Brexit?

The transnational nature of fisheries may limit the UK’s options after leaving the CFP.

Setting unilateral quotas would likely cause international disputes, such as the ‘mackerel wars’ of 2010-11, when negotiations between the European Commission and Iceland and the Faroe Islands broke down.

It is likely that the UK would have to continue negotiating its total allowable catch after Brexit, with it signed up to international agreements that require it to ensure “proper conservation” of fish stocks and to co-operate with regional or global organisations in achieving this, especially where stocks are shared.

The UK’s ability to restrict access to its waters may be limited by historical claims by European fishermen. In the past, tribunals and international courts have often ruled in favour of historic access rights to waters and against those looking to limit access.

Will devolved countries have a say on fisheries policy after Brexit?

Fisheries policy is devolved in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, but currently the CFP provides an overarching policy to which all adhere. Therefore, there is potential for differing fisheries policies in the UK after we leave the EU.

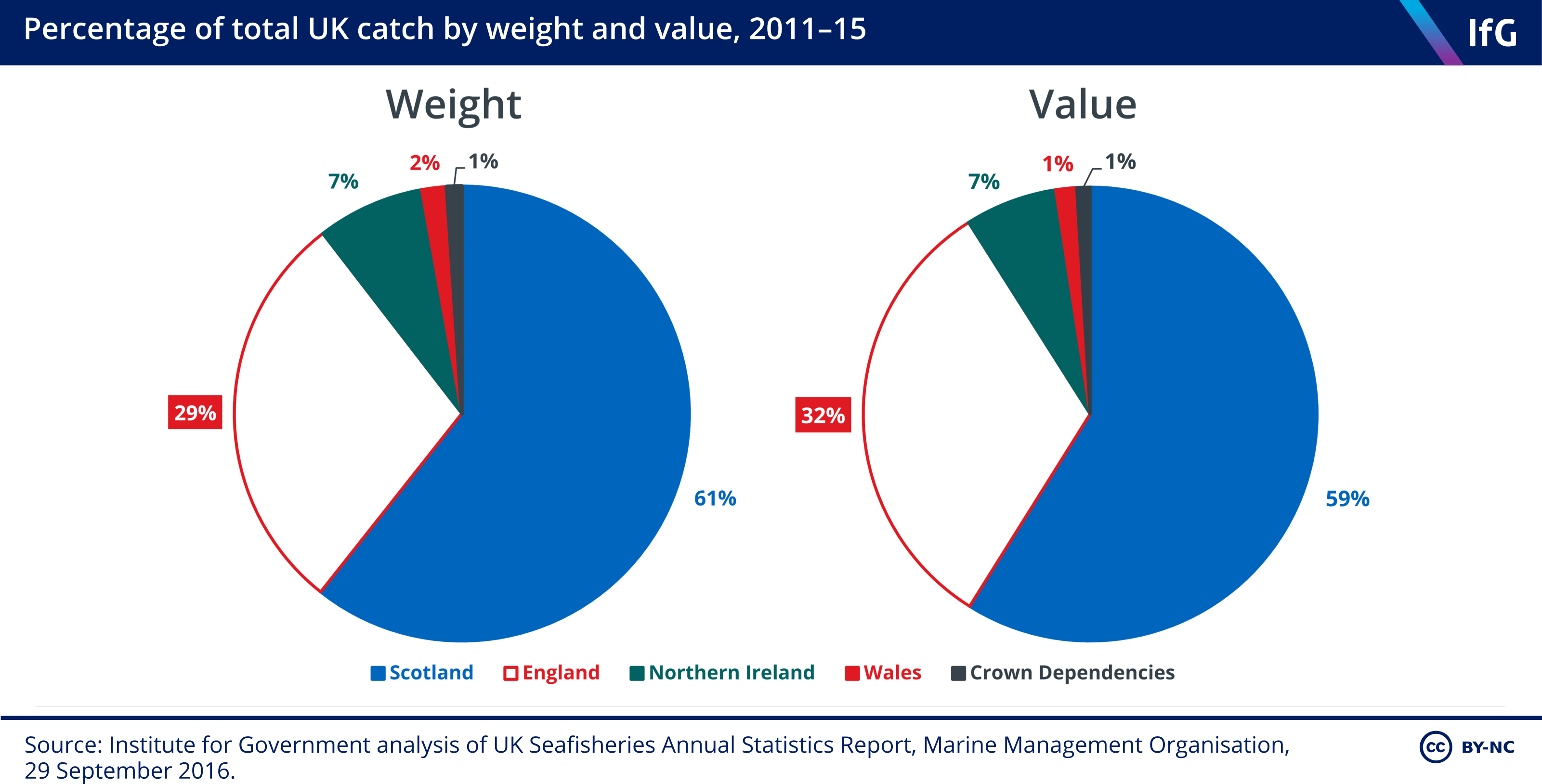

Of all devolved administrations, Scotland is likely to benefit most from Brexit when it comes to fishing. Well over half of the total weight and value of the UK’s catch is landed by the Scottish fishing fleet, and Scottish waters account for over 60% of UK waters. Negotiations between the UK and Scottish governments may create tension if priorities over fishing diverge.

- Topic

- Brexit Devolution