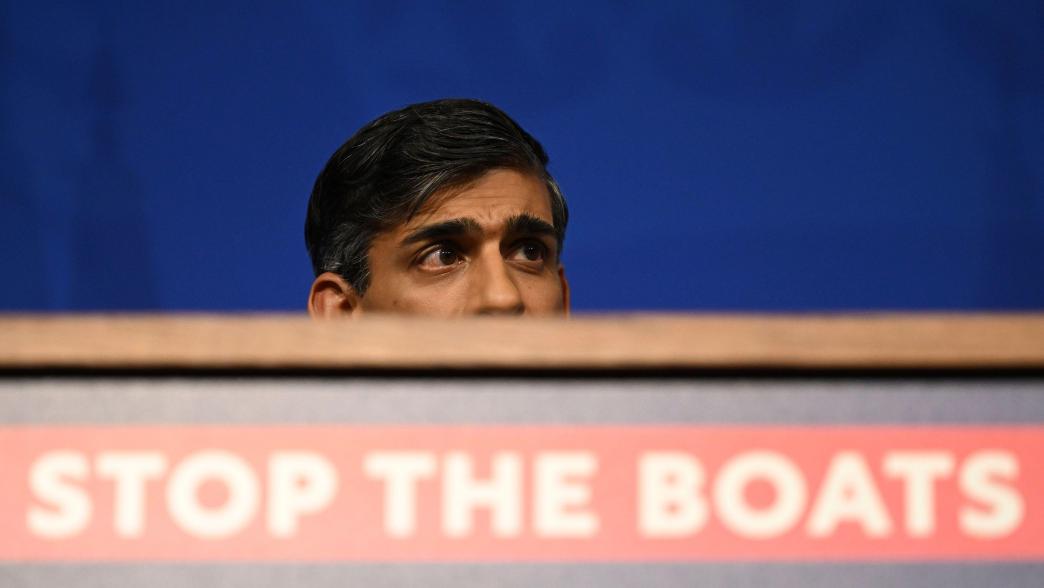

The Supreme Court’s Rwanda verdict and Rishi Sunak’s response: what happens next?

Will the government’s new Rwanda asylum policy plan work?

Jonathan Jones explains the Supreme Court’s judgment on the government’s Rwanda asylum policy – and says Rishi Sunak’s plan to ensure “flights are heading off in the spring” is neither straightforward or risk-free

The Supreme Court’s judgment is a decisive loss for the government

The Supreme Court has held unanimously that the government’s Rwanda scheme (under which asylum seekers would be sent to Rwanda to have their claims decided there) is unlawful. The court found that there were substantial grounds for believing that asylum seekers sent to Rwanda would face a real risk of ill-treatment as a result of “refoulement” (being returned) to their country of origin. Refoulement is prohibited by numerous international law instruments, including the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the UN Refugee Convention, the UN Convention against Torture, and the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Those instruments have been given effect in UK national law by the Human Rights Act 1998, the Asylum and Immigration Appeals Act 1993, the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 and the Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants etc) Act 2004. The Supreme Court was at pains therefore to point out that the case did not hinge solely on the ECHR or the Human Rights Act.

Applying that body of law to the evidence about conditions and past practice in Rwanda, in particular the evidence of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Supreme Court agreed with a majority of the Court of Appeal that there was a real risk that asylum claims would not be determined properly, and that asylum seekers would therefore be at risk of being returned directly or indirectly to their country of origin and suffering ill-treatment there.

A separate cross-appeal by one of the claimants, arguing that the Rwanda policy was unlawful on grounds based on retained EU law, failed.

This is a decisive loss for the government. Its attempt to claim victory on the point of principle – that removing asylum seekers to a safe third country is lawful – is pretty desperate, since that point was not in doubt. The Supreme Court has found that Rwanda is not safe, so the current scheme is unlawful.

Sunak's response is a new treaty and an emergency bill

While “respecting” the Supreme Court’s ruling, the government’s response has been defiant. Much of the detail remains to be seen, but the main elements of the government’s plan appear to be:

- a revised treaty with Rwanda, to replace the current Memorandum of Understanding; and

- an emergency bill which will (somehow) declare Rwanda to be safe and prevent further court challenges under UK domestic law.

The following are some guesses, and some questions, about what this might entail.

A new treaty has a lot of work to do

The current scheme is embodied in a Memorandum of Understanding between the UK and Rwanda. It is not legally binding and cannot be relied on in any court. The plan is apparently to replace this with a treaty which will be binding between the two states under international law.

Simply changing the legal nature of the document however will plainly not address the concerns identified by the Supreme Court. So presumably the new treaty will make substantive changes too, for example to provide additional safeguards for how the claims of UK asylum-seekers will be handled and how they will be treated if their claims fail. (It has even been suggested, bizarrely, that unsuccessful claimants will be returned to the UK.)

But additional words will not be enough either. The question is whether there can be sufficient confidence that the Rwandan authorities will in practice observe any such additional safeguards – in other words, that conditions in Rwanda will in fact be safe.

On that, the treaty has a lot of work to do. The Supreme Court identified a whole range of reasons for concluding that Rwanda is not currently a safe place to send asylum seekers. They include: the country’s poor human rights record; serious and systematic defects in its procedures and institutions for processing asylum claims, not least its own practice of refoulement and of returning high numbers of claimants to known conflict zones; the Rwandan government’s poor level of understanding of its obligations under international asylum law; and its failure to comply with an obligation of non-refoulement in a previous agreement with Israel.

The Supreme Court observed that the necessary changes to Rwanda’s structure and systems might be possible in future, but that such changes:

“ … may not be straightforward [perhaps an understatement], as they require an appreciation that the current approach is inadequate, a change of attitudes, and effective training and monitoring.”

Maybe, though, the government has concluded that the new treaty will meet all these concerns and will indeed make Rwanda safe.

In which case – why does it need domestic legislation too?

An emergency bill could only change UK domestic law

The plan for emergency primary legislation rather suggests that the new treaty, on its own, will not do the trick and meet the concerns set out by the Supreme Court.

What might such a bill say? Again we don’t have the detail. It looks as though it will, somehow, tell the courts to regard Rwanda as safe for all relevant purposes. The bill might also say that this deeming provision is to override any other, potentially inconsistent, law (for example the Human Rights Act 1998). That would be a version of the “notwithstanding clause” favoured by Suella Braverman. The bill might go further and (for example) declare inconsistent orders of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) to be unenforceable. (Section 55 of the Illegal Migration Act 2023 already provides for Ministers to choose whether or not to comply with rule 39 interim orders of the ECtHR, though that section is not yet in force.)

The idea of declaring Rwanda to be safe is a startling one. It would amount to parliament making an assessment of fact (about arrangements in Rwanda) which is directly contrary to the recent findings of the Supreme Court. Would it work though? I think it might, as a matter of domestic law. Ultimately, one would expect the (UK) courts to give effect to such primary legislation, if drafted sufficiently tightly and unambiguously. That would (probably) close off challenges in the domestic courts.

Even if the bill did not explicitly exclude the application of the Human Rights Act, under that Act the courts cannot strike down primary legislation. They can only make a declaration of incompatibility under section 4, leaving it up to the government to decide how (if at all) to respond.

But this part of the plan is not straightforward or risk-free either. First, the government needs to get the bill through parliament – including, of course, the House of Lords. The Lords might well have objections to a bill with major constitutional implications, particularly one which was perceived to breach the UK’s international law obligations under the ECHR or other instruments. There is no manifesto commitment to such legislation. And time for the government to bypass the Lords by using the Parliament Acts is fast running out, since those Acts effectively allow the Lords to delay a bill for a year.

But even if parliament does pass the bill, it can only change UK domestic law. It can’t override the UK’s obligations under international law (we have been here before with the Internal Market Bill and the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill). In particular, it cannot prevent a claimant (prevented by the new legislation from bringing a claim in the UK courts) from taking a case to the ECtHR in Strasbourg. Nor can it bind that court, which will make its own assessment of whether the Rwanda is in fact safe for ECHR purposes. And it can’t prevent the Strasbourg court from making rulings against the UK if, on all the evidence (including the UK’s new treaty), it still believes Rwanda is not safe.

The prime minister’s language about “not [allowing] any foreign court, like the European Court of Human Rights, to block these flights” suggests he would be prepared to defy any such ruling. That would put the UK in conflict with the ECHR, the Strasbourg court and the Council of Europe. It might also put the PM in conflict with some of his ministers, including the lord chancellor and the attorney general. Ultimately it could put the UK on the path to leaving (or being ejected from) the ECHR. Some people think that has been the plan all along.

Rishi Sunak's Rwanda plan: will any of it actually happen?

But a lot has to happen before then. The government needs to produce the detail of its treaty and emergency bill. Parliament – including the House of Lords – has to have its say. There may yet be further legal challenges, either in the UK or in Strasbourg. And an election is not so far off. I wonder if those flights will ever take off.

- Keywords

- General election Immigration Foreign affairs Law

- Political party

- Conservative

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- Home Office

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak James Cleverly

- Publisher

- Institute for Government