Keir Starmer’s NHS targets are not without risk

Stuart Hoddinott says Keir Starmer’s mission to drive improvement in the health service cannot be built on targets alone

Targets can improve NHS performance if used in the right way, but Stuart Hoddinott says Keir Starmer’s mission to drive improvement in the health service cannot be built on targets alone

The third of Labour’s five missions is building an NHS fit for the future, with Keir Starmer outlining a range of policies that his party will implement if they win the next general election. Among those are interventions such as expanding the number of self-referral routes to secondary care, increased investment in health technology, and a shift in focus to prevention. But, on acute care, the most notable commitment was that the NHS would return to hitting targets on waiting times for A&E, diagnostic tests, elective and cancer care, and ambulance response times, within five years of Labour entering government.

This is ambitious, but it is commendable that Labour has given a clear metric against which to measure performance. This is in contrast to Rishi Sunak’s vague and harder-to-measure pledge to improve waiting times in the NHS. It is also an echo of the targets which the Blair government used to raise NHS performance. But those past achievements also show that targets alone will not build an NHS fit for the future.

Targets can drive improvements

Targets were used extensively by the Blair government and contributed to the substantial improvements in NHS performance over that period.

But their use is controversial – and with good reason. Excessive focus on targets, rather than delivering acceptable standards of care, was identified by the Francis Inquiry as one of the main causes of the many failures in the Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust. There is extensive evidence that the use of targets can result in public services prioritising easy wins rather than deeper improvements, stops doctors and nurses exercising their professional judgment, and can create a culture of compliance.

However, previous IfG research has found there is good evidence that setting a clear target incentivised hospitals to focus on improving performance and, in the case of the A&E target, led to better patient outcomes, and associated drops in mortality.

Judicious use of targets is therefore justified.

Labour’s timetable is ambitious

Labour has committed to hitting this new suite of targets five years after taking office. This is ambitious. None of these targets have been hit since 2016 or earlier and hospital performance reached record lows across almost every metric in the last year. Worse, performance in different areas is interrelated: a large backlog in elective care makes it harder to reduce A&E waiting times, and vice versa. This makes implementation of solutions that much more difficult, as all areas need to improve simultaneously.

The Blair government introduced the 4-hour A&E target and the 18-week elective target in 2004. And, while the NHS met those targets only four years later – in 2008 – a future Labour government will find it much harder to deliver comparable performance improvements in such a short time period.

Blair era targets came alongside higher funding and increased Trust autonomy

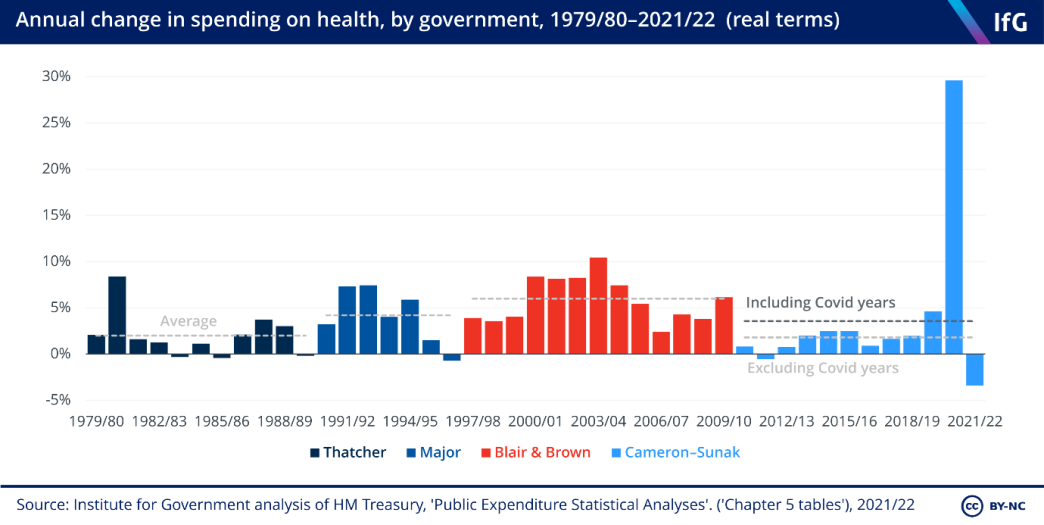

Starmer has said little about how Labour intends to fund the interventions necessary to meet the targets, and it is unlikely that a Starmer-led Labour government will be able to match the spending increases that Blair provided in the early 2000s.

Those funding increases served two purposes. First, and most obviously, it allowed the service to invest in areas that would facilitate increased capacity and activity. Second, it also acted as a signal to NHS staff that the government was supporting them to meet these targets. Because, when targets feel unachievable due to insufficient funding – as is currently the case, it can lead to staff feeling demoralised and defeatist, in turn making it more difficult to hit the target. 4 https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-12/Strategies%20to%20reduce%20waiting%20times%202022.pdf , p.50

The current government has budgeted for 0.7% and 1.8% real-terms increases in spending on the NHS in 2023/24 and 2024/25 respectively. Beyond then, the government has forecast 1% real-terms increases in spending on all public services for each of the three years to 2027/28. The NHS will likely receive larger than 1% increases, due to its “protected” status. But, even if spending increases somewhere in the range of 2%-3% per year, it will still fall well below the 6% year-on-year increases between 1997/98 and 2009/10.

While NHS productivity can be improved, that will likely require upfront investment in areas such as IT, estates, and research and development, as opposed to relying on ambiguous “efficiency savings”, as happens currently. Without that upfront investment, and higher than planned spending envelopes, Starmer will find it hard to meet his targets within five years.

Targets were not the only reason that NHS performance improved under Blair. For example, the creation of Foundation Trusts provided trusts with more autonomy, while the introduction of payment by result (PbR) saw providers receive more funding for increased activity and increased use of patient choice. Targets alone are unlikely to improve performance, as the current Conservative government is discovering.

Keir Starmer has committed to hitting NHS targets. He has also set out a number of policy proposals and reforms, such as a cross-departmental approach to population health. Without additional funding, however, there is no guarantee that Labour’s mission to raise NHS performance will succeed.

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Health NHS Public spending

- Political party

- Labour Conservative

- Position

- Leader of the opposition Prime minister

- Administration

- Blair government Sunak government

- Department

- Department of Health and Social Care

- Public figures

- Keir Starmer Rishi Sunak Tony Blair

- Publisher

- Institute for Government