In the end, there has been no change at the top of government in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland following this month’s elections. But this apparent continuity masks the drama of the government formation process. The process also shows that the governments will have to work with other parties to govern effectively. Akash Paun discusses what’s been occurring.

In Scotland and Wales, unlike at Westminster, First Ministers are appointed (by the Queen) only after receiving the explicit backing of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Senedd respectively. This process came to a conclusion this week as the SNP’s Nicola Sturgeon and Welsh Labour’s Carwyn Jones were reconfirmed in office.

Events in Edinburgh and Cardiff over the past two weeks illustrate how the process works. Holding a nomination vote makes explicit that governments hold power by virtue of their ability to command the confidence of members of the legislature. And with no party holding an outright majority, alternative candidates for the post of first minister have the opportunity to put themselves forward.

Other parties must then show their hand in terms of who they choose to back, and a signal can be sent about the nature of the relationship the Government intends to build with other parties. A debate for another day is whether this process (as the Institute for Government has previously argued) should be introduced at Westminster.

Back to minority rule in Scotland

At Holyrood there was little doubt that Nicola Sturgeon would continue as First Minister, given the scale of the SNP victory. But with the SNP having lost the majority it won in 2011, there was some uncertainty about what the other parties would do.

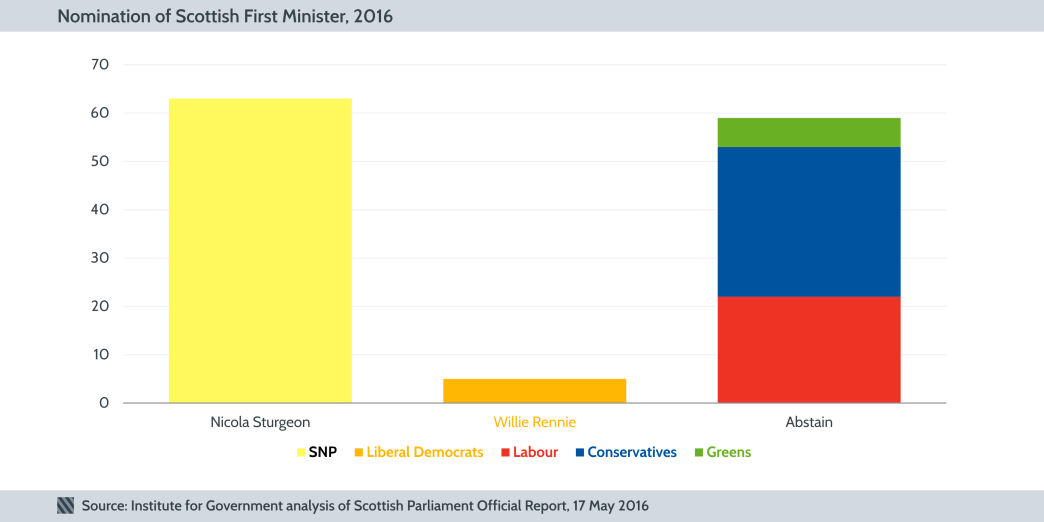

In the end, only Liberal Democrat leader Willie Rennie was proposed as an alternative candidate, ensuring that a vote took place. Rennie, who was backed only by his four party colleagues, was described as a “willing human sacrifice” by Conservative leader Ruth Davidson. Davidson herself, despite now leading the second party in Scotland, was not nominated on the grounds that her party had campaigned to become an “effective opposition”. The other opposition parties abstained from the vote (see the chart below), enabling an SNP minority government to be formed.

The opposition parties made a different choice in 2007, the last time the SNP formed a minority administration. Then, all four major parties put up their leaders for the post of First Minister (see the slider chart below). In the decisive second round vote Alex Salmond defeated outgoing Labour First Minister Jack McConnell with backing from the Greens (and in exchange for the Greens gaining a committee chair). The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats abstained and the SNP took office.

Although her party continues to dominate Scottish politics, Sturgeon will have to reach out to other parties to get legislation and budgets through, as Alex Salmond did successfully for four years. Sturgeon also declared a willingness to strengthen arrangements for parliamentary scrutiny of the First Minister – both in plenary and committee – which she called “an indication of the tone that I want to set in the Scottish Parliament’s fifth session”.

A coalition of sorts emerges in Wales

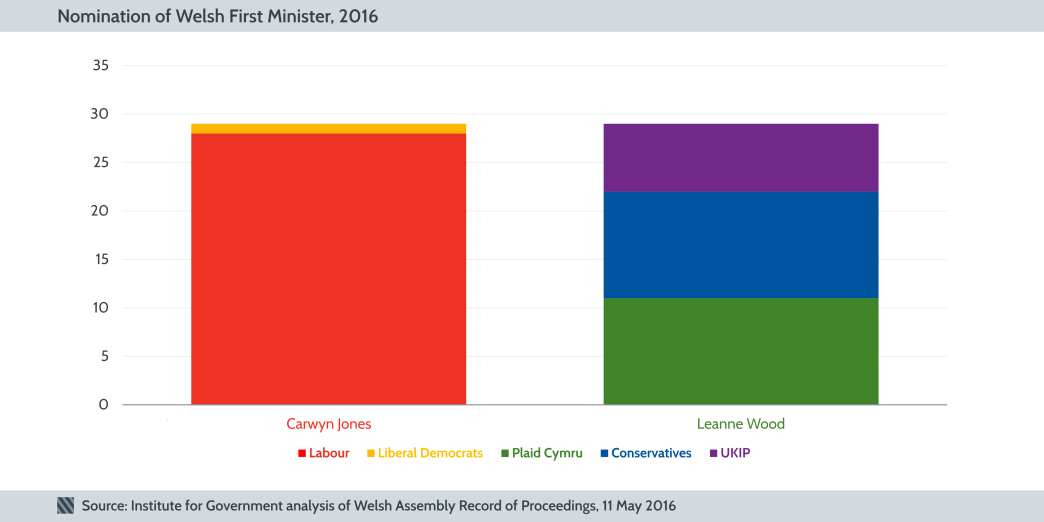

In Wales, the situation in some respects looked similar. The incumbent Labour administration retains a dominant position, having fallen just one seat short of a majority on 5 May, and faces a highly divided opposition. Nonetheless, the first round First Minister nomination vote on 11 May produced the unexpected result of a tie between Labour leader Carwyn Jones and Plaid Cymru’s Leanne Wood. Wood was backed by the Conservatives and UKIP, while Jones secured the support of the Assembly’s sole Liberal Democrat, Kirsty Williams (see chart below).

This brought back memories of 2007, when Plaid, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats came within a whisker of forming a coalition, before the Liberal Democrats pulled the plug on the deal. This time, Plaid pulled back, recognising that with 12 of 60 seats a Plaid government was not a viable option. Instead, an agreement between the nationalists and Labour led to Plaid withdrawing Leanne Wood’s nomination, ensuring that Labour retains the hold on the top job in Cardiff it has held since devolution commenced in 1999.

The agreement is a fairly limited affair. In 2007, the two parties eventually formed a full coalition, but this week’s deal is far short of that and does not even commit Plaid to backing Labour on ‘confidence and supply (financial)’ votes. Indeed, following Carwyn Jones’s confirmation (without a vote) as First Minister, Leanne Wood made it clear that this was a “one-off” deal, emphasising that “we are allowing [Jones’s] election as First Minister, but it is not support.” Instead, there will be consultative ‘liaison committees’ on the key issues of finance, legislation and the constitution, as well as agreement on some specific items such as creating a new infrastructure commission.

Meanwhile, Kirsty Williams has taken the education portfolio as part of a “progressive agreement” between Labour and the Liberal Democrats, giving the Government exactly half the Assembly members.

Northern Ireland gains an official opposition at last

Northern Ireland is very different in that its ‘consociational’ constitution requires the joint appointment of a First Minister and Deputy First Minister from the largest unionist and nationalist parties. So there was no choice of candidates put to the Assembly once it was apparent that Arlene Foster’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Martin McGuinness’s Sinn Féin had retained their dominant positions and would continue to govern together.

The more interesting development in Belfast relates to the position of the smaller parties. Up until now, all five main parties have sat together in a power-sharing coalition.

Recent changes enable parties to opt out of government and receive funding to provide an effective opposition to the executive. The Ulster Unionist Party and SDLP have both exercised this option, meaning that there will be significant non-government parties from both nationalist and unionist communities. The non-sectarian Alliance party is also set to turn down the sensitive justice portfolio and go into opposition as well. Northern Ireland compels parties from the different communities to work together in government.

It will be interesting to see how the opposition parties work together, and whether the Government feels the need to reach out to the smaller parties to build a wider consensus on key decisions.

What about Westminster?

In each of the three devolved nations, governments have learnt that they can function effectively only through cooperation between parties. After five years of coalition, Westminster reverted last year to the familiar simplicity of majority rule. In practice though, a rebellious backbench and an assertive House of Lords has left the Prime Minister facing a similar set of challenges to his devolved counterparts in getting his business through parliament. As the country’s political system grows ever more fragmented, this situation seems unlikely to change.