Six things we learnt from budget 2020

In the run-up to the budget, Dr Gemma Tetlow laid out six things she was looking out for and has since assessed what we learnt.

The impact of this Brexit-induced reduction in productivity growth on the UK’s public finances is less obvious – but larger – than the money freed up from its no longer having to make contributions to the EU.

For most of the period since the referendum in 2016, it has not been clear what the UK’s future trading relationship with the EU would be, not least because any final trading arrangements are not exclusively within the government’s gift.

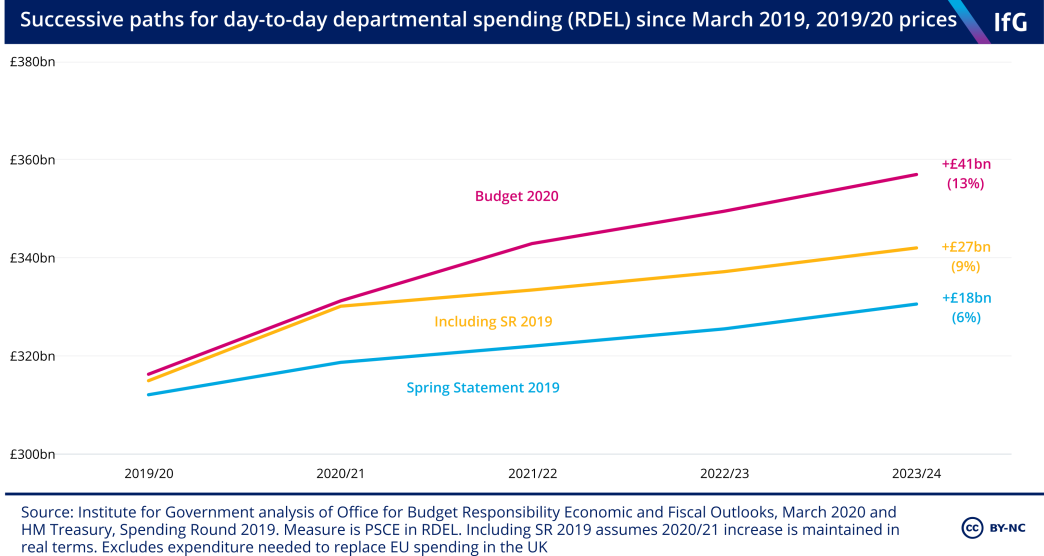

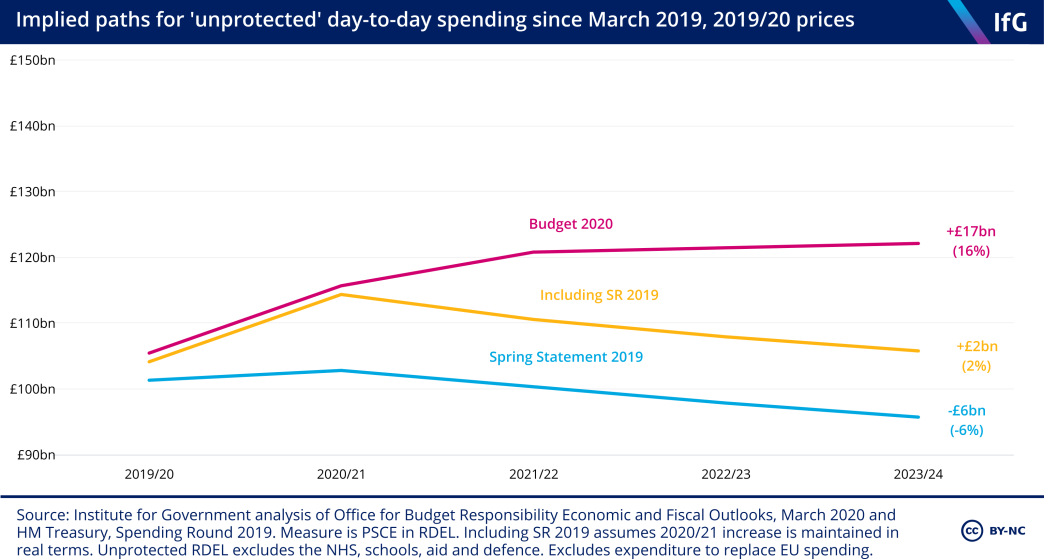

The chancellor announced another chunk of money for public services.

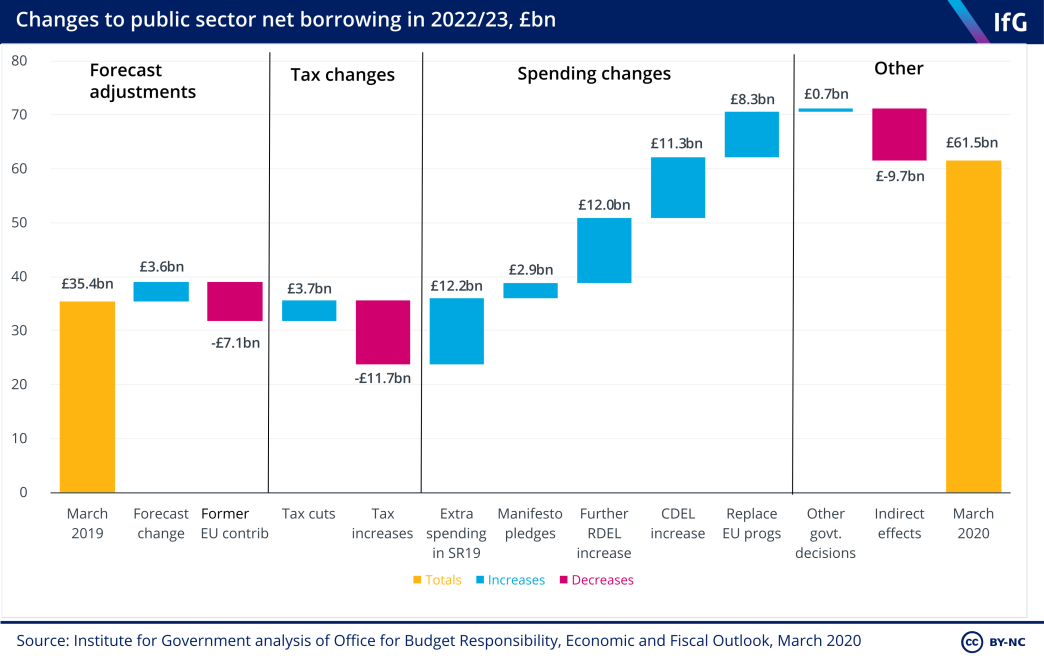

The budget was relatively quiet on tax, albeit enacting a net tax rise (as often happens after elections), mainly through the cancellation of a cut to corporation tax trailed in the manifesto.

This was not the green budget many were hoping for from a government preparing to host the COP26 climate talks in November.