Five things we learnt from the October 2021 budget

Before the budget, we set out five things that the Institute for Government was looking out for in the chancellor’s announcement.

On 27 October, Rishi Sunak delivered his autumn budget and multi-year spending review. Since the last budget in March, most coronavirus restrictions have lifted, and most of the coronavirus-related economic support has ended. This budget and spending review looked forward, setting the path for the government’s economic policies over the rest of the parliament, although it was overshadowed by concerns about labour and supply shortages, rising prices and costs of living.

We at the Institute for Government highlighted five things that we would be looking out for on the day and this page provides our snap analysis in answer to those questions.

Do official forecasts anticipate a ‘cost of living crisis’?

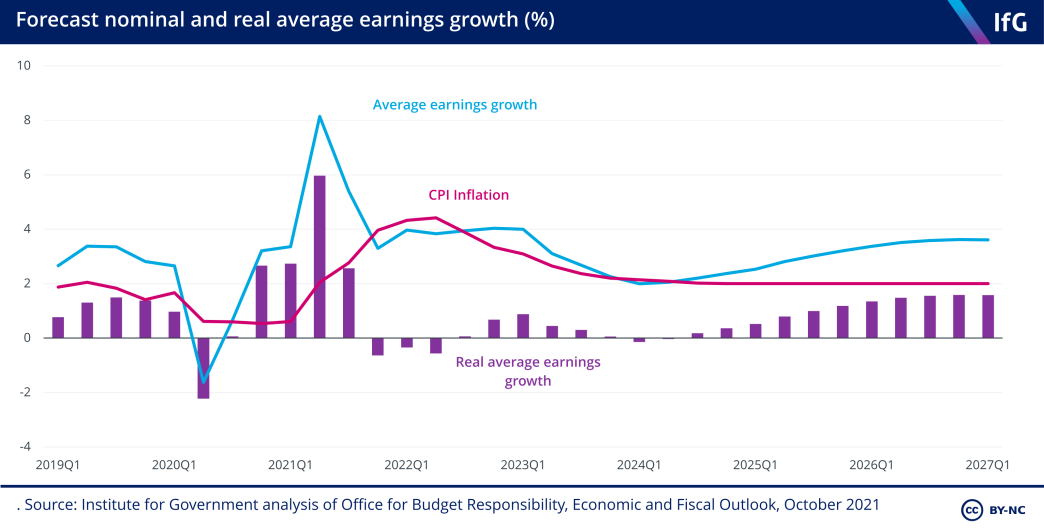

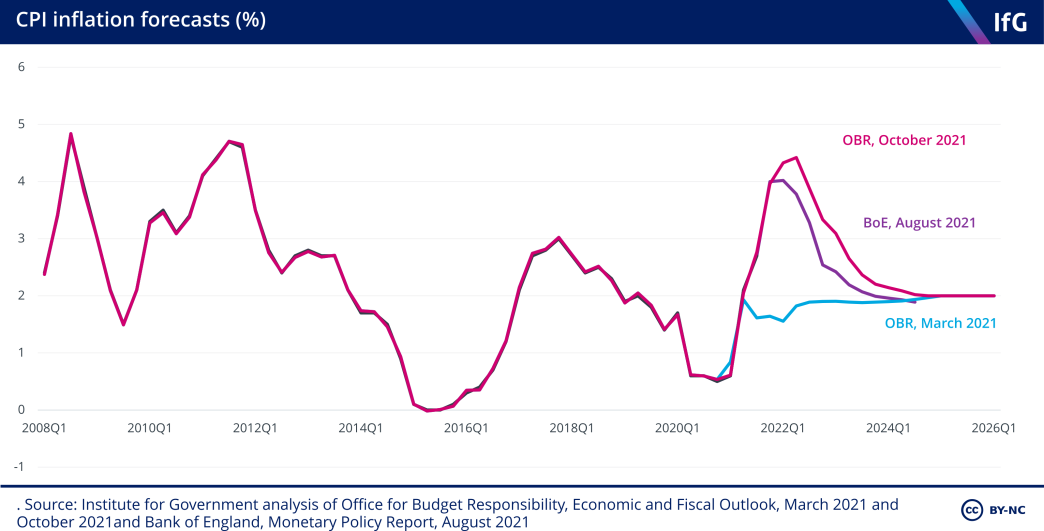

Despite overall good news in the official forecasts, the short-term picture is tricky for the chancellor. The Office for Budget Responsibility expects inflation to peak at over 4% and remain above the Bank of England’s 2% target until 2024.

Households are likely to feel the squeeze of this higher inflation. The OBR expects earnings to grow less quickly than prices over the next year or so, and only really start to keep pace with inflation once it returns to its target. The pain for households will be compounded by policies the chancellor has previously announced – such as the health and social care levy and the end of the temporary £20 per week Universal Credit (UC) uplift. The freeze to the income tax personal allowance and higher-rate threshold from next April will also now bite harder, because those thresholds would otherwise have increased by inflation.

While the chancellor did announce some policy changes in response to the income squeeze, there was no major reversal of the policies above and overall these the new budget measures were modest. The biggest new policy was the cut in the rate at which benefits are taken away when recipients earnings increase (the ‘taper rate’) from 63% back to 55%, which was the original level in the UC system in the early 2010s. This move is a sensible one, but does not reverse the impacts of ending the £20 uplift. The new policy costs around £3 billion per year, about a half of the cost of making the uplift permanent, and only helps those who are in work.

Beyond this, there were no other big policies to ease rising costs of living. Fuel duty was – inevitably – frozen in cash terms for the 12th consecutive year, and alcohol duty was cut on some drinks: frequent drinkers of draught beer and rosé wine may notice a small benefit. The minimum wage will also be increased in line with the recommendations of the Low Pay Commission.

Overall, then, the short-term message from the budget is that household incomes are likely to be squeezed over the next couple of years – and unless you are an earner on UC or a minimum wage worker, there is not much that the chancellor has announced to cushion the impact.

Rishi Sunak was handed a substantial fiscal windfall of just over £30 billion a by the Office for Budget Responsibility

How big is the chancellor’s fiscal windfall, and how will he spend it?

Rishi Sunak was handed a substantial fiscal windfall by the official fiscal forecaster – the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) – in Wednesday’s budget. Two factors moved in the chancellor’s favour, delivering him a windfall of just over £30 billion a year.

First, the OBR now thinks the pandemic will do less long-term damage than it previously feared. Second, evidence from tax receipts this year, combined with stronger forecast growth in nominal incomes, coupled with the planned freeze in income tax thresholds, means that the OBR thinks the economy will be more “tax rich” in future. Put another way, that means it now thinks the government will be taking a larger share of every pound of income generated in the UK.

The chancellor chose to bank most of this windfall, building in a cushion of over £25 billion against his self-imposed fiscal rule to make sure that day-to-day spending is covered by tax revenues from 2024/25. The rest (roughly £5 billion a year) he gave away. He was able to top-up his giveaways further by tax rises and spending cuts elsewhere – in particular, reducing the generosity of state pension increases next year, generating £6.5 billion a year.

The beneficiaries were: recipients of Universal Credit through the lower taper rate; motorists through the fuel duty freeze; businesses through cuts to business rates; banks through confirmation of the lower bank surcharge; drinkers of many types of alcohol; and some public services, especially for the next couple of years.

Frontloading the spending settlement should make it easier for public services to tackle any Covid backlogs quickly.

What will the spending review reveal about the government’s public services priorities?

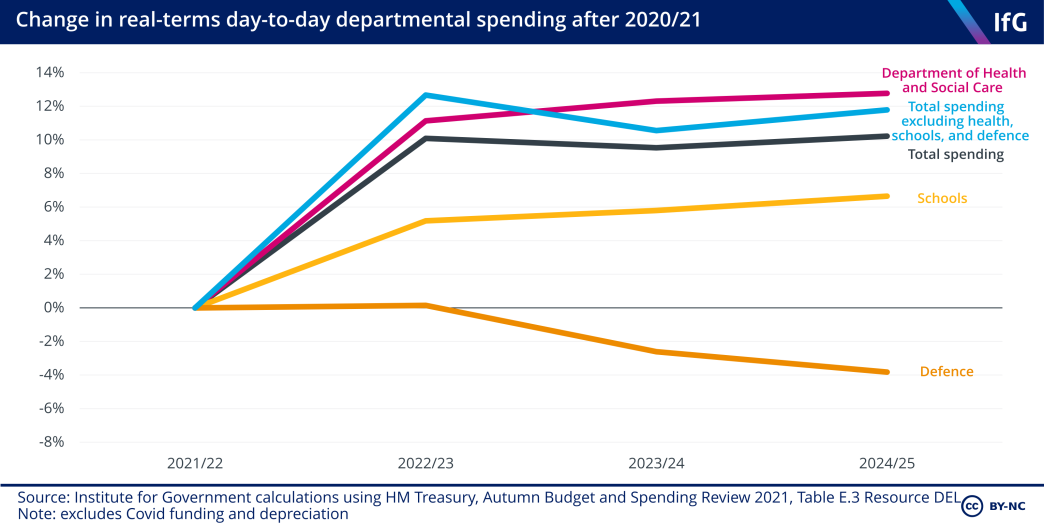

The government plans to increase total day-to-day public spending – covering most staff spending and spending on public services – by 10% in real terms between 2021/22 and 2024/25, with some funds earmarked to address backlogs. Although the chancellor saved most of his fiscal windfall, he was still able to increase overall day-to-day spending substantially compared to his previous plans – especially in the short term.

The spending settlement is no longer backloaded, in contrast to the spending envelope that Sunak had outlined before the budget. Before the spending review, day-to-day spending outside of health, schools, and defence was set to fall in real terms in the first year of the spending review, before increasing to 7% above 2021/22 levels in real-terms by 2024/25. However, the government now plans to increase spending rapidly in real-terms – by almost 13% – between 2021/22 and 2022/23, before it falls slightly in 2023/24. In 2024/25, it is set to be 12% above 2021/22 levels.

Local authority spending power – the amount of money local authorities have to spend from government grants, council tax, and business rates – will increase by 3% each year in real terms (or by 9.3% cumulatively by 2024/25). This should provide local authorities with money to increase spending on adult social care and support vulnerable children who may have been missed during the pandemic, although it may not be enough to support all of those in need, given the other pressures of an ageing population and the cost of social care reform. But how much of that higher spending will come from increases in central government grants, and how much will instead need to come from (as yet unannounced) increases in council tax and other locally-raised revenues, is as yet unclear.

Likewise, the Ministry of Justice’s budget, another department facing big Covid pressures, will increase by 4.1% per year in real terms between 2021/22 and 2024/25, part of which will be used to expand court capacity to tackle the backlog of criminal court cases and accommodate the expected increase in the number of prisoners.

Frontloading the spending settlement should make it easier for public services to tackle any Covid backlogs quickly – and some of the extra spending announced was designed specifically to tackle backlogs. On top of the money already announced in early September to reduce elective care waiting times, the government announced £0.5bn to help the criminal justice system recover from the pandemic, and £1.8bn to address lost learning in schools. This money will help, but the critical question is how the government will find the additional staff and physical resources needed to return backlogs to pre-pandemic levels quickly.

The government also announced that it will lift the public sector pay cap, with specific increases subject to independent pay review bodies’ recommendations. This is welcome, and should prevent public sector recruitment and retention problems from getting worse, although it also increases costs for departments. The Ministry of Justice, for example, which spent £4.1bn of its budget on staff in 2020/21,[1] would need to spend £4.7bn on staff in 2024/25 to ensure that public sector wages rose in line with average earnings, eating up some of the higher spending announced today.

-

Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Justice Annual Report and Accounts 2019 to 2020, 19 November 2020, www.gov.uk/government/publications/ministry-of-justice-annual-report-and-accounts-2019-to-2020

The spending review does not give us any clue about how the government's levelling up objectives will be achieved, nor how the government will measure its progress towards meeting them.

Will we learn more about what ‘levelling up’ means?

Rishi Sunak told cabinet on the morning of the budget that levelling up would be a ‘golden thread’ running through the autumn budget and the spending review.[1] We have previously argued that levelling up needs to be more clearly defined if it is to be a success, but we have ended today not much the wiser on the government’s priorities.

There is still no sign of the promised white paper on levelling up and English devolution. The government has now allocated three years’ worth of funding to departments without outlining its priorities for this ambitious and cross-departmental agenda, which risks departments spending money allocated on incoherent or inconsistent policies rather than using the white paper to guide them.

As part of the spending review, the Treasury has agreed priority outcomes with departments.[2] These give some sense of which departments are responsible for delivering levelling up and the metrics against which they will be judged, though they have not significantly changed since the one-year spending review in 2020. The seven departments with levelling-up related outcomes in 2020 (Department for Education, Department for Transport, Department for International Trade, Department for Work and Pension, HM Treasury, Northern Ireland Office, and Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities) all have the same outcomes this time around, aside from some minor tinkering with the underlying metrics. The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) has had its outcome – previously “Improve and protect the public’s health… while reducing health inequalities” – amended to “Improve, protect and level up the nation’s health, including reducing regional disparities”, but most of the metrics by which success will be judged remain the same.

All this suggests the government’s thinking on levelling up has not changed a huge amount since autumn 2020. With the exception of DHSC and the Department for Education, which focus on public services, most of the outcomes are targeted at productivity, economic growth and jobs. While it is helpful to know how the government intends to measure success in these areas, the most recent statements from the government suggest this is only one part of the levelling up picture.

Neil O’Brien, the government’s levelling up adviser and junior minister in the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, said during the Conservative Party Conference that “empower[ing] local leaders and communities” and “restor[ing] local pride” are important parts of the levelling up agenda.[3] The spending review does not give us any clue about how those objectives will be achieved, nor how the government will measure its progress towards meeting them.

Net zero got the briefest of mentions in the budget speech.

How will the government deliver net zero?

Net zero got the briefest of mentions in the budget speech.

The chancellor reiterated spending announced in the net zero strategy last week, but did not add to it. He again lauded the success of the government’s green bonds, but did not point out that they will not be used to finance spending beyond that allowed fiscal rules. T

There was no clear direction on tax. The chancellor made a change to business rates to reduce a disincentive to make buildings more energy efficient. This had been asked for by the CBI to encourage businesses to invest some carbon saving improvements.

Air Passenger Duty (APD) was reformed along lines previously consulted on. A new ultra long-haul band of APD will raise prices for the furthest flyers is estimated to reduce passenger journeys by around 23,000 a year. But the government reduced the rate for air travel within the UK, even in the mainland where a lower carbon alternative exists. This estimated to add another 410,000 passenger journeys a year – and is an odd message to send the week before COP26 opens in Glasgow.

The most costly, but also the least surprising move, was yet another cash freeze in fuel duty. The chancellor majored on how much that long-lasting freeze had saved motorists. But he gave no indication of any longer-term Treasury thinking on how to replace those revenues as the vehicle fleet goes electric.

In last week’s net zero review, there were hints of an extended emissions trading scheme, and a call for evidence on switching the burden of taxes from electricity to gas. Neither were mentioned in the budget. The chancellor resisted calls from Labour for a temporary VAT cut on domestic fuel and power, preferring instead to compensate less well off households through the Universal Credit taper.

The budget will have reinforced the impression that net zero is far down the chancellor’s priority list. There was no sign of a coherent net zero tax strategy. And, as the Office for Budget Responsibility noted, the Treasury did not include any estimate of the impact of its measures on the UK’s carbon emissions. It should.

- Position

- Chancellor of the exchequer

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government