Six things we learned from budget 2021

We at the Institute for Government had six questions in mind ahead of the budget and this page provides our snap analysis in answer to those questions

On 3 March, Rishi Sunak delivered his second budget as chancellor, although he had made 13 fiscal announcements in the year between his first and second budgets as he has responded to the coronavirus crisis.

Following the announcement of the government’s plan for exiting lockdown, the budget had three main parts: continued support for the economy while the lockdown remains in place, plans for tax rises in the medium term to help repair the public finances, and various measures to aid future economic growth and restructuring.

We at the Institute for Government had six questions in mind ahead of the budget and this page provides our snap analysis in answer to those questions.

1. What is the chancellor’s plan for supporting the economy while economic restrictions remain in place?

One of Rishi Sunak’s big tasks in this budget was to deliver on the promise that Boris Johnson made last week that “the government will continue to do whatever it takes to protect jobs and livelihoods across the UK” while coronavirus restrictions remain in place. The Institute for Government had argued that the chancellor’s plan needed to support the prime minister’s roadmap for exiting lockdown and that failing to do so would risk undermining the whole plan.

The budget largely delivered on this, extending the main support programmes so they continue beyond the point at which the prime minister intends to be able to lift the lockdown. The furlough scheme and support for the self-employed will be extended to the end of September, as will the £20-per-week uplift in Universal Credit. The business rates holiday will be extended until the end of June, with a two-thirds cut for the rest of 2021/22. But he has refrained from reprising anything like last summer’s Eat Out to Help Out scheme aimed at stimulating a recovery for the hospitality sector, which the Institute and others noted was inconsistent with efforts elsewhere in government to contain the spread of the virus. Instead, he announced a new programme of ‘restart grants’ for businesses as they open over the next couple of months.

The extension of the furlough scheme gives some leeway beyond the 21 June date when the prime minister hopes to be able to remove almost all economic restrictions. It does, however, still give a fixed end date, which caused problems last October when the Treasury was very slow to change its policy even as it became increasingly clear that the economy could not reopen as the chancellor had hoped. The real test, therefore, of whether the chancellor has learnt from this experience would come if the government had to delay lifting restrictions for much longer than currently planned.

Sunak has again chosen to continue to offer largely the same support to all businesses – for example, the furlough scheme will remain open to all until the same date even though some sectors are already largely uninhibited, while others (like international travel) are likely to remain constrained even after mid-June. As the Institute noted last year, the risk of this approach is that it will provide poor value for taxpayer money, as public funds will increasingly be used to prop up unviable jobs as the economy reopens.

But the chancellor has plugged some of the gaps in earlier support – in particular, now that self-employed people have filed their 2019/20 tax returns, he has extended the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme to those for whom that was their first year of self-employment, which is estimated to benefit over 600,000 people. Since the government’s stated rationale for excluding that group was purely administrative – that it did not have enough information on their profits – it is welcome that the support has been extended. But it does raise the question of whether that support ought now to be back-dated.

As a result of a faster reopening and the effect of the new temporary ‘super-deduction’ boosting business investment, the OBR now expects the economy to recover more quickly than it previously thought.

2. What is the outlook for the recovery?

Many will have tuned in to Rishi Sunak’s budget to get a sense of what lies ahead for the UK economy, once restrictions lift and the economy reopens. For this the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR’s) forecast, which accompanies each budget, will have been key.

The economic picture in this latest OBR’s forecast is a complicated one. Since its last forecast, in November, public health restrictions and the prevalence of the coronavirus have been worse than expected. However, the success of the vaccine rollout has also surpassed expectations.

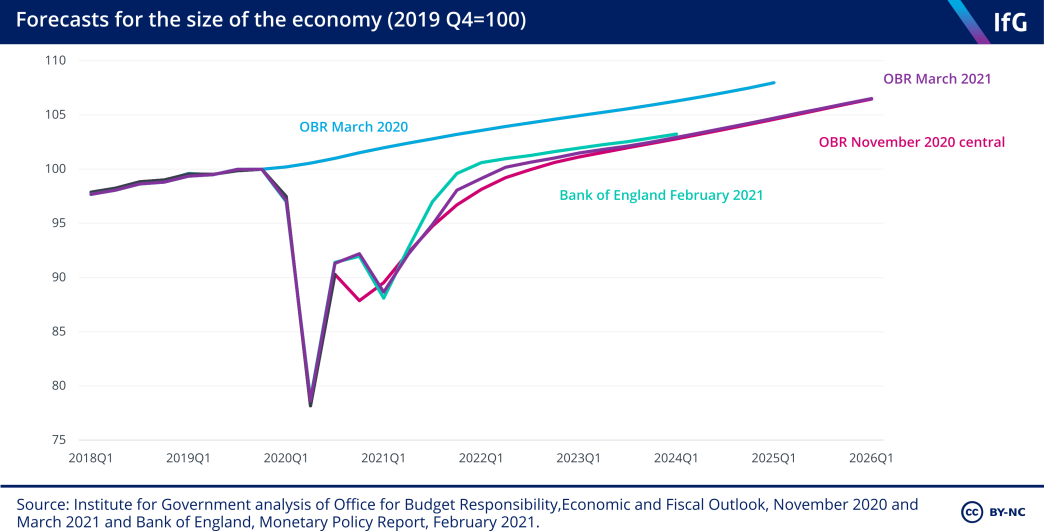

As a result of a faster reopening and the effect of the new temporary ‘super-deduction’ boosting business investment, the OBR now expects the economy to recover more quickly than it previously thought. Rather than reaching its pre-crisis level in early 2023, it now predicts the economy will get there by mid-2022.

However, the OBR does not think this faster bounce back will translate into a fuller economic recovery. It still expects that the economy will be 3% smaller in 2025 than it forecast in March 2020, its last pre-pandemic forecast.

This judgement about the long-term impact of coronavirus on the economy is the most important in the forecast. A smaller economy in the medium term means lower tax revenue and a higher deficit, implying the need for fiscal consolidation at some point. It is also important because it means there is less of a role for stimulus policy in the short term. If coronavirus has done substantial damage to the supply side of the economy, it will not, once the worst of the pandemic has passed and restrictions are eased, be operating significantly below its potential output and so there is little that demand stimulus will achieve except higher inflation.

However, as well as being an important judgement, it is also – as members of the OBR’s Budget Responsibility Committee were keen to stress on Wednesday – an uncertain one, given the unprecedented nature of the Covid shock. We do not know for sure how much damage coronavirus will have done to the economy, and indications of this will only start to emerge once the restrictions lift and the support policies are rolled back.

Despite the rapid bounce back in growth this year and next, then, overall the OBR is relatively gloomy about the prospects of a sustained recovery back to the pre-crisis growth path. We should all hope that this particular forecast judgement is proved too gloomy and the long-term economic damage from Covid is smaller.

3. How is Rishi Sunak approaching the recovery phase?

Back in July, when Rishi Sunak unveiled his ‘plan for jobs’, he announced an array of recovery measures aimed at stimulating the economic recovery – including the Green Homes Grant, Eat Out to Help Out, a VAT holiday for the hospitality sector, a stamp duty holiday and programmes to help young people find jobs. That attempt to launch a recovery proved premature as the virus surged in the autumn and winter. This budget was his second bite at the cherry.

Some of the measures announced in July are still in place or were extended. The VAT holiday for hospitality and the stamp duty holiday were extended to the end of September. And the Kickstart and Restart jobs schemes are still in place. However, there was no mention of the Green Homes Grant (for which most of the funding is being withdrawn from end of March) and no return of Eat Out to Help Out.

Instead, the main new stimulus measure the chancellor announced was the investment ‘super-deduction’, whereby companies can deduct 130% of qualifying investment expenditure from profit for corporation tax purposes. This is a huge incentive for businesses to invest, and to invest in the next two years rather than later when the old, much less generous, regime of capital allowances will return. The Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR’s) forecasts predict it will increase business investment by 10% (£20bn) in 2022/23, and as a result it comes with a hefty price tag in the short term: £25bn in total across 2021/22 and 2022/23. This amounts to a 20% cut in corporation tax revenues over those two years. The OBR estimates that this stimulus is about 10 times the size of the measures used to try to boost business investment after the 2008 financial crisis.

The government has decided not to enact measures that could stimulate other parts of the economy, notably consumer spending. This may be because many households have built up savings during the pandemic. The OBR expects one quarter of additional pandemic savings will be spent over the next five years, so the Treasury may have decided that no additional measures were needed to stimulate that spending once the economic restrictions lift.

While the super-deduction is a big measure, the budget overall is quite light on stimulus for the recovery. The chancellor has not decided to try to ‘run the economy hot’ – to err on the side of too much stimulus to try to maximise economic growth at the risk of inflation – as some economists argue Joe Biden is doing in the US. Sunak is instead taking a more cautious approach, although this may in part reflect the different circumstance he finds himself in on this side of the pond. Biden only has one or two opportunities a year to pass fiscal measures; Sunak made no fewer than 14 separate announcements last year. If it looks like the recovery is flagging, we may well see more stimulus from Sunak in the coming months.

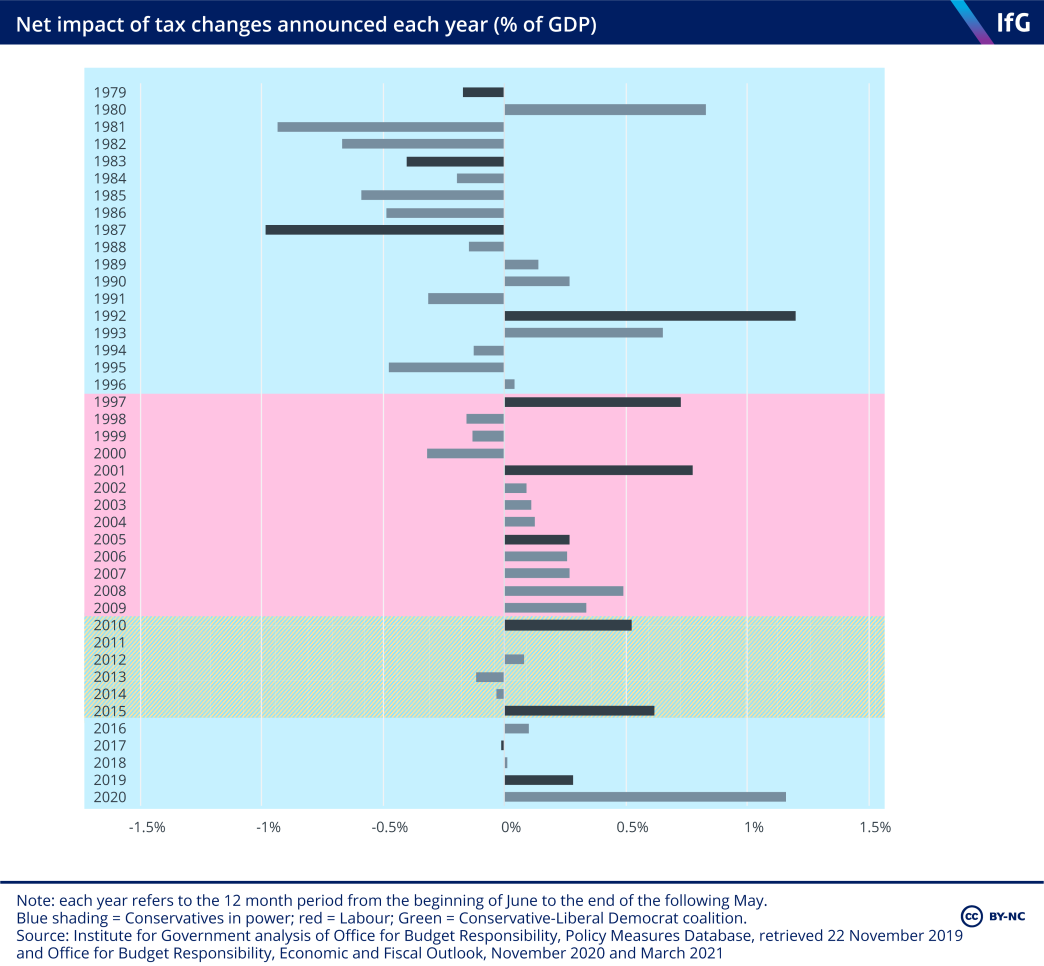

The budget set out substantial tax rises worth 1.1% of national income (or £23bn in today’s terms) which is the largest net tax rise announced in any budget since Norman Lamont’s in 1993.

4. Is fiscal conservatism dead?

The Conservative Party won office in 2019 on a manifesto that pledged not to borrow for day-to-day spending and to leave debt lower at the end of the parliament than the level they inherited – and last autumn, the chancellor told the Conservative Party Conference that “this Conservative government will always balance the books”.

The pandemic blew the chancellor a long way off course but his budget set out substantial tax rises that – based on current economic forecasts – do enough to get him back on track to borrow only for investment by 2025/26. That has been achieved predominantly through a net tax rise worth 1.1% of national income (or £23bn in today’s terms). This is the largest net tax rise announced in any budget since Norman Lamont’s in 1993.

Rishi Sunak said it was too soon to lay out precise new fiscal rules – to replace those originally set by Philip Hammond. But he was clear about what it means to him to be fiscally responsible. He said the state should not pay for everyday public spending, that debt cannot keep rising, and that the government should only borrow to invest. The plans laid out in the budget meet these objectives in the medium term.

The plan for getting there does almost the exact opposite of many of the policies adopted by former Conservative chancellor George Osborne. Sunak is relying almost entirely on tax rises to balance the books, rather than relying on spending cuts as Osborne did after 2010. Furthermore, Sunak’s main tax rises reverse some of the cuts that Osborne introduced: freezing income tax thresholds, after Osborne devoted substantial resources to increasing them faster than inflation; raising the main rate of corporation tax, reversing much of the rate cut that Osborne implemented. The only areas where Sunak has continued in the direction Osborne started are on fuel duty – which continues to be frozen – and the lifetime limit on private pension contributions, also frozen.

The sorts of tax measures that Sunak has deployed are ones that previous Institute work has highlighted as being relatively easy for chancellors to implement – freezing thresholds to allow inflation to drag more of people’s income and assets into higher tax bands, and raising business taxes rather than personal taxes. But he made no mention of some of the more substantive reforms that had previously been trailed – such as tackling the disparity in tax paid by employees, the self-employed and company owner-managers.

Public services were allocated huge sums of money in last year’s spending review to help them respond to coronavirus, but the government did not allocate any new money to them in the budget.

5. What extra money is there for public services?

Public services were allocated huge sums of money in last year’s spending review to help them respond to coronavirus, but the government did not allocate any new money to them in the budget. The chancellor announced that the government will spend a total of £2.5bn next year to support vaccine rollout (£1.7bn), school ‘catch-up’ (£0.4bn) and the devolved nations (£0.4bn), drawn from the Covid reserve fund originally announced in the 2020 spending review.

This is not surprising given the £79.4bn of public services support announced in that review – which included a reserve fund of £46.6bn to deal with any coronavirus pressures in 2020/21 and 2021/22, and the government chose not to increase this funding at this budget.

[CHART]

The bigger challenge facing public services is that the government’s medium-term spending envelope – the amount of money it intends to spend over the next five years and will allocate to departments at the next spending review – is now even tighter than it was in November.

The government has not allocated any money for any Covid-related cost pressures after 2021/22, such as an annual vaccination programme or support for people struggling with mental illness as a result of the pandemic.

Excluding emergency coronavirus spending, the government plans for day-to-day spending to increase by 2.1% in real terms each year after 2021/22. Given existing commitments to the NHS, schools, defence, and aid, this implies a decrease in real-terms spending for all other ‘unprotected’ areas of government spending in 2022/23.*

Such a cut will make it extremely difficult to address backlogs, meet any additional public service demands arising from the pandemic, and return services to their pre-crisis performance levels. Criminal courts, for example, will struggle to increase sitting days and reduce the backlog of court cases waiting to be heard if HM Courts and Tribunal Service’s budget is cut in real terms.

The existing settlements for the NHS and schools may also be revised upwards if the government decides to spend more on health and social care to build resilience for future pandemics, spends more to clear surgery backlogs after 2021/22, or spends more to ameliorate the face-to-face learning time that children in school have lost over the past year.

The government has made clear that this path for spending is not final and they have promised to set out the amount of money that will be allocated among departments at the 2021 spending review in due course. Given the potential long-lasting impact of the pandemic on public services and the government’s promises, the chancellor may find that the current plans are too tight to deliver. Otherwise, most public services will have another difficult few years ahead.

*The government has reduced its spending plans relative to those outlined in the 2020 spending review following reductions in the OBRs forecast for GDP deflator growth after 2021/22. The reductions in the forecast are a consequence of difficulties measuring public sector output during the pandemic. The change in the OBR’s forecast is therefore a direct result of disruption to public services rather than a genuine reduction in the costs of delivering public services.

The prime minister has said he wants to secure a “green recovery” but Rishi Sunak’s 2020 budget largely failed to offer signals about how the government would achieve that.

6. Does the budget give any sign of serious commitment to a green recovery?

The prime minister has said he wants to secure a “green recovery” but Rishi Sunak’s 2020 budget largely failed to offer signals about how the government would achieve that. His 2021 budget was a chance to add more weight to the prime minister’s words.

Sunak did not do that to any great extent. He announced the establishment of a new National Infrastructure Bank in Leeds (with an initial capitalisation of £12bn), funding for offshore wind, a green retail savings product and a green bond.

But once again, green measures were in the margins of his budget speech. He chose to maintain the now decade-long freeze to fuel duty, reducing taxes on the burning of petrol and diesel (the small print offered a hint that “future rates will be considered in the context of the UK’s net zero commitment”). There was no wider move towards developing a ‘net zero tax strategy’, for instance by moving some of the tax burden from electricity to gas.

Nor was there much in terms of spending measures to accelerate the transition in sectors that have fallen behind, like transport and housing. On the latter, there was no detail on what, if anything, will replace the Green Homes Grant – a scheme announced at the last budget which has flopped with low take-up. Most of the funding is being withdrawn at the end of the month. There were measures to boost digital skills but not green skills, such as replacing gas boilers.

An intriguing point, however, was the inclusion of net zero in the mandate of the Bank of England. It remains to be seen what long-term changes this will lead to, but the Bank of England has said it will adjust its corporate bond-buying programme in response.[1]

The Treasury’s interim net zero review was frank about the need to confront the costs of decarbonisation – though notably it was signed by the exchequer secretary not the chancellor. This budget did little to back it up – or signal that the UK’s recovery from Covid would be an especially green one.

- Shankleman J and Meakin L, Bank of England Gets New Mandate to Drive Net-Zero Goals, Bloomberg, 3 March 2021, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-03/bank-of-england-gets-new-mandate-to-drive-net-zero-goals

- Topic

- Public finances Coronavirus

- Position

- Chancellor of the exchequer

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government