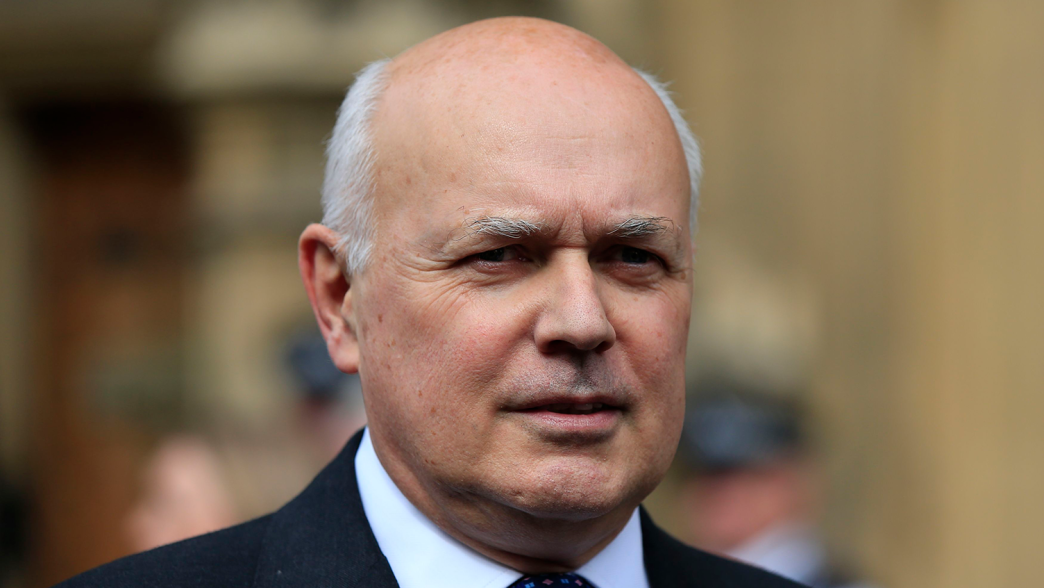

Iain Duncan Smith

Iain Duncan Smith was interviewed on 11 July 2016 for the Institute for Government’s Ministers Reflect project.

Sir Iain Duncan Smith was secretary of state for work and pensions between 2010 and 2016. He has been a Conservative MP since 1992 and was party leader from 2001 to 2003.

Nicola Hughes (NH): You’d done quite a lot of thinking in opposition and with your work through the CSJ [Centre for Social Justice] about welfare policy and some of the ideas that you wanted to pursue, how did you translate what you were then thinking and doing there once you got into government?

Iain Duncan Smith (IDS): Well the first person I brought in, was my adviser, Philippa Stroud who had been the Director of the CSJ, so we had a sense of direction. I didn’t have to do a huge amount of policy work to begin with because the DWP [Department for Work and Pensions], on hearing that I’d been appointed, had almost to a man and woman visited the CSJ site and crashed it on the same day that I was appointed.

I didn’t go straight to the DWP, because I had a whole series of prior arrangements. I was speaking at a conference about early intervention and I just thought, I’d just get on with that. I finally got a call at about 2.30 in the afternoon from a rather frustrated person who declared himself to be my Principal Private Secretary: ‘Was I planning to come into the department at any particular point,’ he said ‘because everybody else had gone into their departments?’ – So, finally at about 2.30, he was outside with the car. I had a very brief conversation with the Permanent Secretary Sir Leigh Lewis, which was really around how did I want to be addressed, and then he handed me a file, about how the department actually functioned, whilst very good, I didn’t read it fully as I found it better to speak to the heads of the sections and walk around speaking to some of the civil servants. And at that point, I had some others senior officials in. That was when they told me that for some reason they could no longer access the CSJ website… they’d all been looking at my website earlier and Philippa Stroud had called me to say ‘the website has crashed twice, can you tell them to stop visiting the website!’ [laughter] But they’d all started printing everything off from the website that we produced. So, the department was fairly well informed, unusually they said, because normally when a minister comes in, we have to sit down and talk to them and ask ‘but,’ they said, ‘with you, you’re an open book because you had everything on your website.’

The DWP [Department for Work and Pensions], on hearing that I’d been appointed, had almost to a man and woman visited the CSJ site and crashed it on the same day that I was appointed

Peter Riddell (PR): Wasn’t there another point, that the person you were talking to, of course, was Theresa [May]? Because she’d been the actual Shadow and that therefore, they’d worked up her ideas.

IDS: They had indeed.

PR: Which were of course in the manifesto.

IDS: It was in the manifesto, one of the things that had been agreed, was the take back of Tax Credits into the department. As you know, Gordon Brown set up tax credits and kept it, in essence, in the Treasury, but it was kept essentially in HMRC [HM Revenue and Customs] and it had never really functioned at all well. HMRC has never really known how to work that level because they don’t do that level of debt; they do bigger tax debt, they had never done such relatively low level processing, as the DWP had. So, I inherited this plan which the Permanent Secretary immediately wanted to talk to me about: ‘Could we do this?’ And I said ‘Well, I have a bigger plan actually on my hands which I want to do, which isn’t in the manifesto, but is something that the Prime Minister [PM] has vaguely said “Work it up and agree it with the Chancellor.”’ So, I said ‘I would like to work that up’ and that’s when we started work on Universal Credit [UC]. ‘But in the meantime’, he said, ‘it would help if we had these two together before we went to Universal Credit’, which is, I guess, a logical point. So, we entered discussions with the Chancellor at that point – it can only have been a couple of weeks later – and he said ‘Why don’t we forget about the transfer to the DWP of Tax Credits and work up, instead your plans for Universal Credit?’ I was intrigued that even though it had been in the manifesto, the Treasury clearly didn’t want to make the transfer and so in the intervening couple of weeks, the Treasury managed to kill off the transfer idea. Quite fascinating. This was not my idea, but when I went to see him and said ‘This is your idea, it’s in your manifesto’ and he said ‘Well, I tell you what, I don’t think this is going to work, why don’t we work up your idea and then decide whether we’re going to do it.’

So, I said ‘I would like to work that up’ and that’s when we started work on Universal Credit

Sir Leigh Lewis, an ‘old school’ civil servant, who had run the department successfully for some years, was I think personally a bit disappointed. After all, DWP and HMRC had, it transpired done a considerable amount of work on this in planning for a new government only to find that the Treasury were suddenly saying ‘No’ and he could see his Secretary of State wasn’t pushing to carry it through. Instead, I had agreed to work up the plans for Universal Credit. Quick as a flash though, he put it behind him and realising the importance of UC, started looking at Universal Credit, to figure out how and when it could be implemented. So, that was really the first instance. Also, the department had done quite a lot of background preparation on our other projects such as the Work Programme which had been originally in Breakthrough Britain [2007 CSJ Policy recommendations paper]. So they’d already been working on the manifesto, also some CSJ policy questions were in there as well.

PR: How prepared were you to be actually a minister as opposed to the agenda you had as a minister, because you had your two years or so as leader of the opposition, quite some time before, seven years before. So how prepared did you feel for that, because as you said, you hadn’t been part of the shadow team, you’d been a kind of free-lancer, generating ideas, highly respected as was shown in what happened with your appointment, but not part of the team. So how did you find your preparation for actually being a minister?

IDS: Well, I had never been a minister before and I wasn’t a PPS [Parliamentary Private Secretary], I was far too rebellious early on, as you will remember. I had never been really close to government. I was pretty much aware of how government worked, but nothing really prepares you for government till you actually do it. I’d read a few books and got close to government on a number of occasions seeing how it worked. We did a study at the CSJ about how a Conservative Opposition could move into government and make progress immediately, rather than spending a year figuring out how it works so we could implement our programme. We created a team, which wrote an informative report drawing on the expertise of retired Permanent Secretaries. So there was a body of work on which I had also been part of and so I wasn’t a complete stranger to the way the system worked. And, of course, being leader of the opposition to a degree gives one a sense of what ones responsibility would be, but having said that, I went into government and having been on the boards of companies and various other things, I had, at least, an understanding of how organisations work. But it takes you a little while to figure out how the civil service works because it’s a very, very different animal from a business and a very different animal from a political party. Culturally, you do take time to figure that out and to decide how best you’re going to use it, as it were, so it does take a little bit of time.

I had never been really close to government. I was pretty much aware of how government worked, but nothing really prepares you for government till you actually do it

PR: What were the challenges, the cultural challenges?

IDS: Well, I think the first thing you’ve got to overcome when you walk through the door is that everybody is being almost far too nice to you. Whilst that is helpful, it can also overwhelm you as you suddenly discover you are working on their plan and not yours. You need to take a pace back and try and get some perspective on what it was you came in to do, in reality, you need to figure out how from this calm and orderly organisation you can find that grit in the oyster that will help create the pearl of policy. What are the issues? What are the potential practical and as important political problems?’ I managed to get to that reasonably quickly, however it takes time to get to know which of your civil servants have the kind of analytical and questioning approach. That’s why one has to put the pressure on early to see who reacts by forcing everybody to focus. I wanted people to be honest about what the difficulties were. That’s the biggest cultural barrier. The Civil Service, legitimately see it as their role to deliver on politicians’ policy demands and this can sometimes make them resistant to the idea that they should inform you early of problems. Because they see it as their role to deliver, they become determined to do that but in so doing can lose sight of the other priorities that the politician faces.

The first thing you’ve got to overcome when you walk through the door is that everybody is being almost far too nice to you

For example, as secretary of state more than a minister, you realise quite quickly that your department is, in a peculiar way, a kind of fiefdom. The department itself is proud of itself and it likes to see its Secretary of State demonstrate its importance by being seen as important politically. Within days, the first thing that amused me was when I went to the first Cabinet. When I came back, my Principal Private Secretary said ‘All that’s very good; looked very good on camera. Everyone’s very pleased; you’re right up at the top of the table, unusual for our department which has been down at the bottom of the table under the last Government; you’re literally next door to the Chancellor!’ and I laughed about that, because it hadn’t even occurred to me that the placing around the table mattered, but I came to realise, it really does matter. It matters both at Cabinet, but it also matters to the department because they then feel, ‘We’ve got a senior Cabinet Minister, so now we’re going to have a better shot at getting things done that we want done.’ So little things like that, which only the Civil Service would notice, nobody else would notice, I began to realise that they read the runes of all of these things and it matters really where you are and what you’re doing and how you’re treated in the firmament, as it were, of the Cabinet and political government.

Huge amounts of work take place at the drop of a hat and sometimes some of it I thought unnecessary because what I came to discover was that the Civil Servants felt they weren’t doing their job unless they were filling my box with draft papers and lists of decisions which they maintained had to be resolved. Often I felt there was a degree of self-justification. That is why I think it takes so long to get one’s head around the way the department works and who is good and who is not. How ridiculous then that the average time my predecessors from the Labour government were in post was nine months. I realised after nine months, I still didn’t know that much about the running of the department. I didn’t know how anybody could possibly have known that. So that meant the department was in effect, running itself. Of course my predecessors as secretary of state might take some top-level decisions but they couldn’t have had enough time to ensure that such policy decisions were acted on further down the food chain. After all, it took me more than nine months to figure out how the system worked, after all, the DWP is a huge department, I mean on a scale beyond anything else.

I realised after nine months, I still didn’t know that much about the running of the department. I didn’t know how anybody could possibly have known that

So, as a secretary of state you had to very quickly get across to them how you want to work. I’m quite informal. One of the big questions they wanted to settle was ‘How formal do you want to be?’ We agreed that at meetings they would refer to me as ‘Secretary of State’ but I was much more informal with my private office. Leigh Lewis made me laugh when he sighed with relief and said, ‘We’re rather tired of Christian names, you know, the ‘call me Tony’ stuff.’ I personally don’t really like titles very much; I never have done. I think we had a reasonably relaxed relationship. However, when it came to the private office, the relationship was different. I operated on a much more informal basis. As ministers discover, a well-run private office is invaluable and they need to ensure you miss nothing of importance. They have to quickly pick up on your way of doing things and translate that to the department so that the work is completed to your satisfaction. That is why I encouraged them to come to me with issues as they erupted rather than write notes in the box. I left the door open, if they wanted to come in, they just poked their head round the corner and might say a word to me or something and if I wanted somebody, I’d go outside the door and call somebody by their Christian name. So, it wasn’t very formal.

As ministers discover, a well-run private office is invaluable

PR: What about the political team, I mean obviously there was the coalition but as you say, it was an enormous department and therefore you had to delegate quite a lot to other ministers, how did that work? How did delegation work?

IDS: I’d like to think I am a delegator. I’ve been in business enough to know that you have to delegate, but you must ensure people do the work. So, we divvied up all the responsibilities. I sat with the Principal Private Secretary, that’s almost the first thing you do, and look at the lists and there are huge lists in the department of things that need someone responsible for them. We carved these responsibilities up and looked at how they would best work. At that time, I had Chris Grayling in [then Minister of State for Employment]. I worked very closely with him to keep his employment section, focused on their big reform, the Work Programme. Yet there were other responsibilities he also took on besides. For example, I hadn’t realised we were responsible for Health and Safety, so after discussion with him, I put Chris Grayling in charge of that as well. There were three [House of] Commons ministers and a [House of Lords] Peer, Lord Freud. I had a Pensions Minister in the case of Steve Webb, he took on responsibility for other areas as well, as did the Disabilities Minister [Maria Miller]. On top of that the Lords Minister David Freud had to handle everything the Commons Ministers did in the Lords, this meant his workload was enormous. We eventually got someone to support him but not until much later. I constantly had to review each of these areas to ensure balance.

It dawned on me that someone would have to cover each responsibility at the dispatch box which didn’t just mean answer for them but also seek to change and improve poorly functioning programmes. So, it takes you a little while to get your head round all that. Once it is all apportioned then you need to have very regular meetings with ministers – we had a Monday morning meeting that I set up immediately which first of all had all the department in, you know, Perm[anent] Secretary, the communications teams and then private office and things and there we would talk about what the media was on about during the course of the weekend and where we were going and what our issues were; then we’d talk about programmes and what might be coming up, look at the grid to see what was happening, whether we had a speech to make or something in the Commons or Lords. Then they [the department] would leave and we’d have a half hour political meeting. Lots of my colleagues separated the coalition partners out and did them as Conservatives. I never did; I kept Steve in, so we did it as a coalition political meeting.

PR: We’ve done Steve in this series.

IDS: We’re very good friends and there was a high degree of trust between us. We didn’t have any problem about sorting out different coalition priorities. He was very good about times when he said ‘I’m going to be unable to help you on that one because our position is going to be quite different.’ But the political meeting was important, because it allowed the PPSs [Parliamentary Private Secretaries] and the ministers to raise their objections about what’s going on in the department and concerns about individuals and there were one or two names that were always coming up. They might raise concerns about particular officials and their performance on programmes. They might want me to speak to the Permanent Secretary and get them moved and so on.

So ministers might debate the merits of some officials and then complain that they had raised it already with the Permanent Secretary but nothing had happened. They reasoned that it took me to insist before it might happen. That’s when it became clear to me that the whole department seems to want to be in the Secretary of State’s office – as one Private Secretary said to me, ‘that’s what they work for. They feel like they haven’t made it unless they’re sitting across the desk from you on a programme or something else.’ The problem was stopping them all coming into your office, because even though they’re working with a minister, for them, the great moment is when they come into your office. I hadn’t realised that that meant so much to civil servants to be in your office and that’s why you need a really good private office to say, ‘Well, he doesn’t need to deal with this right now, this needs to go down to the minister’ because everyone is pushing to be in your office. That was a bit of an eye-opener to me. And what I tried to do was to keep pushing back and saying look, you know, if they say ‘So-and-so wants a decision.’ I’d think, ‘Give it to the minister.’ I used to make a habit of walking down the corridor to pop my head into a minister’s office unannounced and say, ‘Let’s talk about a couple of issues’. My view was quite clear. It was vital that as ministers we kept closely in touch otherwise we would end up communicating through the officials and that would create problems for our political agenda. So I used to visit different ministers to talk about issues and that worked with me. So, it was just getting the balance right between the ministerial side, always taking the minister’s side, although sometimes realising the minister was making a fuss about something which they didn’t need to, so I would try and quietly get them off their high horse rather than, you know, saying ‘Tell them to do this’. I always felt the civil servant shouldn’t be the person to go and say the Secretary of State doesn’t want to do something. It will be me saying to the minister, ‘I think we can do this a different way.’

It was vital that as ministers we kept closely in touch otherwise… that would create problems for our political agenda

NH: You mentioned Philippa before, how did you use your special advisers?

IDS: I have to tell you good special advisers are worth their weight in gold. I don’t see them, as is often the view, as a set of political hatchet merchants, quite the contrary. I used mine really as progress chasers. So, to begin with I had a media special adviser, who is vital, liaising with the communications team; I had Philippa, who was already different from most advisers as we had worked together for some years and her remarkable qualities I knew complimented my agenda. As a result, she immediately became the senior special adviser – an informal Chief of Staff. The way we worked was that Philippa helped me by calmly driving all the key policy work. So, for example with Universal Credit; Philippa read everything that was going to be in my box before I got it, tiding up and deleting any shoddy work. She would just put a line through ill-thought-through sections. If a document was due for a decision from me she would know me well enough to know that I would reject it if it wasn’t right. Sometimes a member of the private office, being chased by a more senior official might ignore her warning and sneak one into the box. What was amusing was I almost invariably did what Philippa said, I would return it, without having discussed it with her. This meant I was free to focus on what became a very wide ranging set of reforms, her work and that of the other spads [special advisers] took enormous pressure off me.

The other thing a good special adviser can do is to ensure that the political objective is met, by attending meetings much further down the ‘food chain’. Philippa Stroud did this as did the other spads. As time went on my spads and the private office worked well together, complementing the work each undertook. That’s why I argued for another spad, because the complexity of the policy work in the department was enormous, dwarfing almost every other department.

I have to tell you good special advisers are worth their weight in gold

PR: You mentioned progress chasing; given you had a big project, how adaptable was the Civil Service to absorbing something as big as that?

IDS: Well, the Universal Credit story is an interesting one and quite illustrative of some of the issues, because it taught me a huge amount about policy implementation and the capability of the Civil Service. When, after negotiations, we all agreed the format of the Universal Credit programme; we signed it off with the Treasury. The Treasury agreed the way we would do it. It was explained to me that the DWP would have a project leader, known as an SRO [Senior Responsible Owner]. The Senior Responsible Owner was appointed and then I attended a number of meetings with them about how they were going to roll it out. They argued that they should start ahead of the completion of the legislation, which was going to take at least a year. I was slightly concerned at that point, because I said the legislation may change. However, it seems that in some earlier programmes, they operated in that way, retrospectively changing elements of the programme as policy changed due to political pressure in the Lords or the Commons. This is one area both I and the department came to discover caused issues later and I would not have had it so, knowing then what I know now. It’s better to see the legislation through first.

In 2011, I became quite worried that when looking at the programme, I was beginning to worry that the programme itself didn’t look to me like it was completely under control, that the plan was progressing well and officials were being honest about the problems they were encountering. There was an issue over the SRO, Terry Moran. I believe he became distracted as he undertook, at the same time the responsibility of running operations, the ‘retail’ end of the department, the job centres, contact centres and the benefit processing centres. The scale of his operational job by its nature distracted him from the day-to-day running of the programme. This became apparent to me in 2011. So, I asked for what I called a ‘red team’ of outsiders to come in and to review the running of the programme. Now, I know there’s an MPA [Major Projects Authority] process, you know, which looks at major projects etcetera and they reported on government projects reasonably regularly, and although they had raised some concerns, I wanted to assure myself that we were doing all that needed to be done. After some bureaucratic delays, the red team reported back to me in early summer 2012. They made it very clear to me that this programme was not progressing in the way it was meant to.

They made it very clear to me that this programme [Universal Credit] was not progressing in the way it was meant to

So, by the beginning of the summer, I called all key people in – there was lists of things that the report pointed out were going wrong. After frank discussions, changes were made to the programme to get it back on track. It became apparent that the SRO’s post needed to be changed and we were fortunate in that we had just taken on a man who had project managed the Terminal 2 rebuild. He also happened to be one of Britain’s leading IT specialists – Philip Langsdale, who immediately offered himself up. Sadly he suffered from MND [Motor Neurone Disease]. He was in a wheelchair by the time he came to us yet notwithstanding his personal health issues, he immediately re-jigged the whole implementation plan. It was his idea to roll the system out at a much slower pace allowing us to re-set elements as we tested them. We later came to refer to this as ‘test and learn.’ Key to this was the end to the ‘big bang’ approach where historically government would develop a programme and launch it in one go, always fraught with risk and that was borne out by the problems with our existing schedule. Many programmes in the past have failed using this method. Sadly, having begun to put the programme back on an ‘even keel,’ he died in December.

The MPA came in to do their regular review. We were clear with them (they were given the ‘Red team’ report) that there had been some significant problems and inevitably they produced a difficult report about the state of the project. This is where the politician has to step up and take responsibility, never an easy role, as facing the House of Commons when there are departmental problems is difficult enough, when the problems concern a flagship programme, and it’s a hard slog. Notwithstanding that both the MPA’s and later the Public Accounts Committee’s report recommendations were already working, as they were based on the Langsdale plan.

The story of Universal Credit is, I believe now, a very successful one and many lessons have been learned on route. For me the most important thing I took away was the way in which the civil servants, from the Permanent Secretary down and Lord Freud, my excellent lieutenant, and I worked together to ensure this vital programme was implemented. During the course of this reset civil servants showed an ability to embrace new ways of working, as did the politicians. I know the Westminster media bubble would rather rake over the problems originally incurred and personalise them but I believe the real point is that by working closely together and being open about problems we faced in delivering the programme and owning agreed solutions, even though they meant a big change in the way such programmes had been implemented before, we have ensured the success of Universal Credit. After all having understood there were issues about the programme early-on, and under intense pressure, far from walking away from it, I saw that the department really believed in delivering UC by the way they showed their determination to do what was necessary to put it right. They were proud that apart from the fact that UC already ensures households go into work quicker, stay longer and earn more, it will end up being delivered under budget, including any of the write downs. I am in turn, proud of the department for embracing this programme and working so creatively to deliver it. After all, as the Permanent Secretary said to me more than once, ‘staff in the job centres love using UC as it allows them to help those on the lowest incomes get back into work quicker.’

The story of Universal Credit is, I believe now, a very successful one and many lessons have been learned on route

I don’t intend to say any more about the details but I do think the lessons are quite vital in changing future programme delivery. In fact, interestingly, John Manzoni [Permanent Secretary of the Cabinet Office] said as much at an Oxford Seminar very early in 2016. He made the point that the way UC was now being developed and rolled out was how all future bid IT programmes should be developed – ‘Test and Learn’, he said may take longer but it ensures delivery. This was at a seminar for the Major Projects Leadership Academy, which I and the Permanent Secretary attended. The two of us ‘tag teamed’ our views of how programme management should work within the Civil Service. In fact we also spoke of how we had set up an internal departmental review, the Major Projects Review Group [MPRG], which met every week to review progress on the department’s major programmes. That is an important point to make. I have used Universal Credit as an example but it was one of a whole series of reforms that we were implementing, whether it was The Work Programme or PIP [Personal Independence Payment], all successfully implemented, the MPRG enabled us to monitor them all much more closely.

John Manzoni’s appointment has helped, as he brought management expertise from the private sector. In subsequent conversations, we agreed that not only does the Civil Service need to implement such programmes in such a way but that there needs in future to be a greater recognition of important skills within the Civil Service, such as programme management that have their own rewards. Also there needs to be a way of informing ministers about how programmes should be delivered and that governments need to understand the length of time realistically allowed for delivery. Also, much more IT development should be done in-house. In the new world of digital development, outsourcing to distant lands of much needed technology should no longer be the norm.

NH: Really interesting, and so two questions from that. The first is what specifically did you see as the ministerial role in implementation?

IDS: Historically, ministers did policy and civil servants did the implementation. This was how we originally approached the Universal Credit programme. But I think we crossed a line quite quickly after that. I believe in future, ministers need to be kept much closer to the development so that in the implementation phase if the team hits a problem over an aspect of policy, the secretary of state or minister can make a decision to modify the policy to accommodate the technological capability. Thus, instead of them twisting themselves in knots trying to make the system work, causing delays, a quick decision on policy can break the log jam. Ultimately, that is the way we came to operate, with [Lord David] Freud [Welfare Reform Minister] into much closer involvement, so daily meetings are now held to resolve such issues. I believe the artificial divide between politicians and civil servants over policy and implementation now needs to be broken down.

I believe the artificial divide between politicians and civil servants over policy and implementation now needs to be broken down

I’ve come to recognise that the private sector is no panacea. Under the previous Labour government, the mantra was that if it was put out to the private sector because they’re motivated by their profit margins, they’ll ensure they do a good job. From experience with a number of our programmes, I could see that was only true to a point. I was drawn to observe that there are badly run companies out there as much as there are badly run departments. OK, it’s usually down to who is running it and the quality of management, however if you have incompetent people running a private company, it doesn’t matter how much profit is in there, they will screw it up. I think such was the pressure to put areas of government work into the hands of the private sector that assumptions have too often been made about motivation. Yet many of these companies are themselves staffed by ex-civil servants. I accept there are benefits to outsourcing but alongside that there needs to be a better understanding of how the Civil Service manages such contracts, in short much stronger contract management. On the Work Programme, after some initial poor delivery issues, the programme became much more efficient because motivated civil servants were eventually tasked to manage key contracts, immediately asking the companies regular and detailed questions about their performance. The way it had operated in the past was that this process was more distant with little intervention early on, relying on the problems to emerge later. However, leaving private companies to their own devices, only to find, too late on, that they were well off-target, created massive problems for the government. That is why a new culture has been introduced in the DWP of aggressive contract oversight. That means if the civil servant manager believes that the programme looks as though it might being going off, they haul the company in and very early demand to see their get well plan. John Manzoni has again been on side with it.

Leaving private companies to their own devices… created massive problems for the government

Universal Credit was another example where we agreed we had to do more development in-house; some of the technology companies were making a financial killing off departments like mine and then being very slow to produce and often chucking it out to India somewhere, then bringing it back and when it didn’t work, taking it back again. This process led to huge delays. Since then, hiring a brilliant IT specialist from the private sector the department has saved huge sums from its IT programmes by driving the contract prices down and bringing developers in-house. This has been a bit of a cultural shift for the Civil Service but one they have embraced with enthusiasm.

I believe the department now is much better than most other departments at managing contracts. After having gone through a difficult period, we made big changes. Also I believe the Civil Service is now having to assimilate a new way of rewarding sector skills, rather than just generalists. The existing system is a pyramid. That means that moving up the ranks towards the position of Permanent Secretary is how people are valued. Yet, I believe they should have a way of rewarding people in the Civil Service who may not be of Permanent Secretary material but are none the less brilliant as programme managers and so on. After all, if a Permanent Secretary’s reputation relies on safe programme delivery, they would want the best. So those who show an aptitude to do these jobs should find good financial rewards. What I believe the modern civil service needs is an in-house capability that gets rewarded, perhaps less emphasis on generalisation and alongside that key skills from software engineering to contract management and programme delivery.

NH: And you said earlier as well about initially when you started, the department seemed very eager to please – do you think that’s part of why some of the early problems and glitches with implementation didn’t get through?

IDS: Yes, as I said before the culture of separate working with the Civil Service and their original propensity to deliver only good news has now stopped – robust honesty now, I believe that is now more characteristic of ministerial meetings at the DWP. Instead, as I previously mentioned, ministers and civil servants need to work closely together for problem solving. This is also a challenge to the politicians who have in the past been content too often to leave delivery to the civil servants. This in turn means a more rational acceptance by the political class of safe delivery as opposed to early delivery. The media love to chastise ministers for delay but so often it is better to accept some delay if it ensures safe delivery. Also, I felt that civil servants probably need to be prepared to be more critical of their colleagues when required. In principle, in a development programme where you are reliant on the other person completing their work to the right standard but instead they hand you shoddy work, it means you cannot do your job. What we discovered was that too often instead of handing it back and demanding that work be completed to the right standard, the individual concerned spent their own valuable time trying to put it right, delaying the whole process. This could be a cultural issue, for I found that the civil service was a tight-knit community where that kind of robust criticism didn’t come naturally to them. That robust relationship is what the private sector in programme development calls quality circles; it will I believe become much more normal for civil servants as well.

The media love to chastise ministers for delay but so often it is better to accept some delay if it ensures safe delivery

PR: What about working in the rest of Whitehall, working with the Treasury, working with Number 10?

IDS: Oh I have already expressed my views about the Treasury, I think…

PR: I have heard. [laughter]

IDS: I would definitely think some re-think on how the Treasury works is required. It seems to many ministers and civil servants, just too dominant. I was just saying the other day, nobody can hardly ever name who the Treasury Secretary is in America, can they really? They may know who the state department head is or who the head of the NSA [National Security Agency] or whatever or even the DoD [Department of Defense] but you can’t name the Treasury Secretary, normally. And there’s a reason for that, because they‘re a finance department. They don’t get involved in policy making and they’re there to serve the government. What’s happened over here, is our Treasury has become far too involved in policy making, a hangover from the way that Gordon Brown structured it. Yet, the Treasury is by its very nature a short-term ministry. After all, why do we have these set piece budgets and then spending reviews? Both have become extensions of the other with the dividing lines blurred. The process means now, ministers and civil servants spend huge amounts of time negotiating with the Treasury, month in, month out; you’re almost perpetually in with the Treasury. Another criticism of the Treasury made to me by departmental civil servants was that they rotated their posts in the Treasury very rapidly. That meant that in areas where agreements had been made, the incoming Treasury civil servant often called previous agreements into question, causing departments to re-negotiate that which had already been agreed. There is need of a re-think in terms of how the Treasury works.

The other problem was that Downing Street tends to become obsessed with the 24-hour news cycle. This heavy emphasis on media increased dramatically under Blair and it carried on with Brown. The problem is I feel that Blair created a Prime Minister’s department, a vastly extended policy unit at Number 10. Yet they don’t have day-to-day responsibility to run anything. Populated as it is by teams of people, beavering away briefing the Prime Minister on what they believe should happen in departments, or was not happening, it created antagonisms. That can often lead to real problems between the Prime Minister and the Secretary of State and that bit always leads to bad feeling. At its worst, those in the policy unit used to call officials in the departments and demand work to be carried out for the Prime Minister urgently. Junior level civil servants would then drop everything when they heard the Prime Minister wanted the work, more often than not the PM has no involvement and it turned out to be someone from Downing Street on a ‘fishing’ expedition. Too often the work was without purpose and turned up in some kind of counter briefing, leading to confusion for the Prime Minister on what the department was doing.

I don’t say that departments themselves don’t create serious problems through their mistakes but I think what happens when you go into government is that over time, departments and Downing Street become like drifting icebergs crashing into each other every now and then. That could be changed: better offices that liaise better, better understanding. More regular catch-ups between the Prime Minister and their secretaries of state.

Over time, departments and Downing Street become like drifting icebergs crashing into each other every now and then

PR: What’s your advice to a new minister – I mean, after all, there may be some by the end of the week?

IDS: You’ve just got to get on top of your brief pretty quickly and get to know the people that are the key people in your area. If you’re a secretary of state, you need to quickly make a point of seeing them, judging them yourself, listening to them, seeing whether they are the kind of people that react when put under pressure. Ministers should not get too puffed up about being a minister and stand on ceremony but earn respect from your officials by listening to those who are meant to be the experts and then challenging all the accepted ways of operating until you can see for yourself if they work. Challenge and encourage civil servants to challenge you back. Ask them serious questions but always act with politeness, even if you have to take a tough position which contradicts theirs. Most of all, remember they are civil servants, not your servants. Too many ministers treat civil servants badly because they can. Secretaries of state whilst defending their ministers shouldn’t be afraid to criticise them if they are behaving badly. The good civil servants you will find are the ones that actually want to drive your agenda, they are like gold dust and they want to take ownership and they’re there with the answers. You look for the civil servant that understands their subject and can command your attention, no matter how junior.

Most of all, remember they are civil servants, not your servants. Too many ministers treat civil servants badly because they can

NH: What about people outside of Whitehall, did you do much external engagement?

IDS: Yes, huge really, because I carried on a lot of what I was doing with the CSJ, so I went and visited lots of charities and voluntary sector groups and things like that. It’s quite important to do that.

NH: Did that help you with some of the things that…?

IDS: Yes, also because the DWP is a delivery department with offices in every town in the UK. I did a lot of visiting of job centres and benefit centres and I loved that because they were really interesting people, the job centre staff. I grew to admire them a great deal. Some MPs are quite critical of them, but I am not. I think there are obviously good people and bad people, but my sense about the DWP job centres is that they were full of ideas and dedicated people. Every time I saw them, they told me why something didn’t work and what we should do to change it and when we got back to the office we’d make the change. I’d often also arrange to bring different people who had impressed me from a job centre or benefit centre into the department for a day, to get them to meet senior civil servants and ministers. I thought it was really good to see them talk to senior officials. They loved it and word travelled round quite quickly. Also, I never gave the centres much more than an hour’s warning. I used to turn up on the day, so they didn’t polish up or anything else. I found they were the most realistic people I came across in the entire department because they dealt every day with people, all kind of areas and difficulties and they told me straight. What was also good about the department was the way that high-flying senior civil servants in Whitehall were regularly sent to spend time in these centres so that they understood how the policies worked on the ground.

PR: What about back here, do you spend a lot of time in Parliament as a secretary of state? Because one of the dilemmas always, particularly when you’ve got a massive business and a demanding department like…?

IDS: It is inevitable that you spend time in Parliament. However it becomes difficult to ensure you spend enough. It’s vital to keep in touch with your colleagues on the back benches before issues erupt. I did try to ensure this happened, I was conscious that I always felt it could have been more. You see, it’s very difficult, ministers get very comfortable sitting in their office, it was the same for me, I was working on huge issues. But I did try and make time, particularly in the early evening, coming over or votes obviously but there’s just so much going on in the department, it was very difficult. If you are not careful, you can begin to lose a sense of Parliament, because it’s just so busy and the department is always demanding your time and if you are conscientious, you have to do it. If you’re not conscientious, you don’t care, you just hand it back to them and say ‘Get on with it’ but I couldn’t do that really. I thought that my job was to try and make things happen and ask questions and so if you do that, then it does put enormous pressure on your life. Having to juggle a huge job, with parliamentary duties, your constituency and your family. I’ve met many ministers from overseas who came to visit and whilst we were talking, I’d have to get up and run to vote. They were often quite astonished, they couldn’t figure out, what I was doing. Our system is unique and although it puts extra pressure on ministers, it also grounds them in reality once surrounded by their parliamentary colleagues speaking to them about constituency problems.

If you are not careful, you can begin to lose a sense of Parliament, because it’s just so busy and the department is always demanding your time

PR: Did your civil servants appreciate the significance of Parliament for you?

IDS: They did and the longer we were together it was as though the whole team was engaged. Particularly when they saw me having to go to the dispatch box at difficult moments. The private office absolutely got it, the stress and the strain, I mean, it’s unbelievably stressful when you have to go to the dispatch box at short notice to answer questions about some issue or other. It’s very tough. So, it is for all ministers and secretaries of state, it’s really important to keep in touch with the House [of Commons] and your backbench colleagues. I used to give my Parliamentary Private Secretary a half hour slot once a week for them to bring anyone in who they thought needed to speak to me. It was my way of valuing their issues and concerns. I don’t think there is any other system in the world that does it like this. It’s pretty abrasive on a minister, to be honest with you: late night sittings, issues about votes and then, you know, UQs [Urgent Questions].

NH: How did you find Select Committees?

IDS: Yes, we had ups and downs with Select Committees, I’m used to dealing with them, so though we had a few rough moments with committees, we also cooperated as well. I never felt that I had to be overly aggressive and by and large the meetings with select committees are a bit more civilised than the chamber of the House of Commons. So generally I think they were OK. As SoS [Secretary of State] I always tried to keep on good terms with the chairman and for the most part I think that was OK. Anne Begg, I got on very well with her and I think subsequently her successor…

PR: Frank Field?

IDS: Frank, yes, I’ve known him very well, from when he was previously chairman back in the nineties and then a minister under Blair. I was ironically the Shadow Secretary of State when he was a minister. But as the new chairman of the committee, I don’t think I faced him for more than about 10 months, then I resigned. One’s private office needs to be tuned into the politics of everything, unlike most civil servants, they need to get the politics. I built up, before the last election, a fantastic private office, who were people who really got what I was doing and sadly they all got broken up after the election. That’s the other bit about the Civil Service that I really found frustrating was that they rotate everybody every couple of years at the most, and it can be really difficult because in dealing with some serious projects, the Secretary of State could do with greater continuity, I understand the need to get greater experience but I found it quite tough to re-establish relationships based on historic policy issues, in the midst of change…

One’s private office needs to be tuned into the politics of everything, unlike most civil servants, they need to get the politics

NH: I mean you, in a sense, are quite unusual in being a DWP Secretary of State who has been around for so long, you served for quite a long time, for the whole five years. How important was that tenure and that stability?

IDS: Very important. I had become acquainted with pretty much everything by the time I left, although there were still surprises. I think, being there for six years was tiring but it meant that I knew people. I knew a lot about the way the department worked, I now know an awful lot about the culture of the Civil Service. I know what they will do and what they can’t do and what is not good to give them. For example, I don’t think they do policy particularly well. Their expertise is in implementation. It’s not really policy. Policy is done by politicians and think tanks and their job was to figure out whether they can implement it. There were some notable exceptions but by and large the balance of our relationship settled and I like to think worked. I had a little party for them after I left here and they were a bit shocked when I decided to go – and they weren’t the only ones. [laughter] You know, it was nice really that they all came to the party, everybody from the Permanent Secretary down to the people from the job centres were in this room, so I had about 50 or 60 people and following that, I had endless notes and emails, which was rather sweet really. You do get close to people if you work so long with them. You begin to care where they go and what their prospects are like, you care about what’s happening to their careers. There were a number of people there that I kept saying should be going somewhere else and I’d say so to the Permanent Secretary and sometimes I’d extoll their virtues even to the Cabinet Secretary.

For all the need to change, on reflection I found the civil servants generally very supportive, particularly the ones I worked closely with. They embraced our large programme of change and were as proud as any politician when it worked on the ground. Six years of enormous reform in such a huge department of state was always bound to be a voyage of discovery but one I like to think was successful for all of us. I certainly am proud to have run such a remarkable department and proud of the dedication showed by so many.

- Topic

- Ministers

- Keywords

- Coalition government

- Political party

- Conservative

- Position

- Secretary of state

- Administration

- Cameron-Clegg coalition government Cameron government

- Department

- Department for Work and Pensions

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Legislature

- House of Commons

- Publisher

- Institute for Government