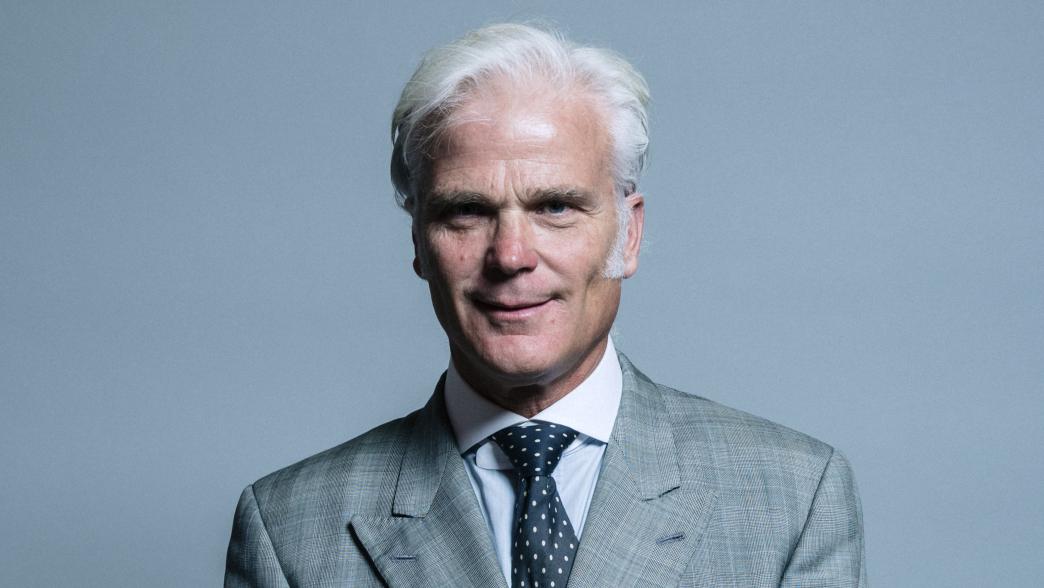

Desmond Swayne

Desmond Swayne reflects on his time in government for the Institute for Government’s Ministers Reflect project.

Sir Desmond Swayne was minister of state for international development between 2014 and 2016. He has been a Conservative MP since 1997 and was parliamentary private secretary to David Cameron (2010–12).

Nicola Hughes (NH): Can we start by talking a bit about your role as Parliamentary Private Secretary [PPS] to David Cameron. Was that helpful preparation?

Desmond Swayne (DS): Yes. I mean I was Cameron’s PPS for seven years, and Michael Howard’s, the previous leader of the party, for a year before that so I had done eight years as Parliamentary Private Secretary to leaders of the party and two of those years were to the Prime Minister. So I had, I think, a fair appreciation of the breadth of government business. I was present for all Cabinet meetings, I was there at 8:30 every morning in the sofa-laden study, I was at the 4pm meeting and I attended a whole breadth of other meetings with him. So I had a fair sense and my perception of government was not wholly dissimilar to what it was in opposition, even from Number 10. You spent 50% of your time trying to find out what the government was doing, and the other 50% trying to stop it!

NH: Could you give us an example of that?

DS: So, absolutely randomly, I remember this ridiculous idea of changing the clocks, double summertime or something, I think it was called. Now, I just remember in the late-1960s going to school in the dark and it was awful. What’s more, when it was put to Parliament after that two-year experiment, the vote to restore the clocks to their proper function was overwhelming. Why would we want to go through this all over again? But it kept coming up. You would find that you would make an intervention into a meeting and kill something off. And then a couple of weeks later, having missed the meeting, you discover it’s all back on again. Outrageous, but there it is!

"…you would make an intervention into a meeting and kill something off. And then a couple of weeks later, having missed the meeting, you discover it’s all back on again."

NH: So that was useful for seeing across the system. When you first went into a department, what were your first few weeks or months like in the job?

DS: Well, very smooth actually. It was a completely different environment. So you’re no longer dealing with the whole of government, into which, let’s be honest, notwithstanding the very significant spend on international development, international development did not feature a great deal. International development was not big in those discussions of either the whole strategic approach of government or indeed, the day-to-day management of the politics of government. It was a quite different experience in the Department in that you were thinking much more about a specific area without, to some extent, the day-to-day distractions. There were some distractions: an amazing amount of distraction and noise from the Crown dependencies. They consume a huge amount of management effort for what they amount to, there was day-to-day management of news stories, whether it be child molestation or the airport in St Helena or whatever. Those distractions are there, but they were not nearly as evident as in Number 10. You do have much more time to think clearly about what the strategy is.

NH: How did you determine what your priorities would be in DfID?

DS: Well, I had been told what my priorities were by the Prime Minister when he appointed me. But naturally I saw them in a particular context when I got to the Department. Certainly, I confess to not being a great strategic thinker myself and I was happy with the direction of the Department that had already been set. I had a great deal of confidence in my Secretary of State, Justine Greening, and her judgement. I was not at any stage desiring to change the direction set by her and the PM. Except in one respect, and that was about the whole question of marketing the commitment that we had made to spending 0.7% of Gross National Income on international development. The attitude I think that prevailed was that given the political consensus on this issue, namely only one political party being actually against it, UKIP, which at that time had no MPs in Parliament at all, why would we want to take up time on such an issue when we don’t need to and there is a political consensus about it? We accept that the view of the voters is very much against this, but hey, we’re not in a political competition for votes on the issue, it is not a vote-determining issue and therefore why would want to rub the noses of the voters in something that they disapprove of? That was an attitude that was certainly there and the Number 10 media grid and all the rest did not favour announcements by DfID.

"…the Number 10 media grid and all the rest did not favour announcements by DfID"

There was one important campaign which was pulled, into which a lot of work had gone. It had been to engage our ethnic minority and diaspora populations with respect to what we were spending in, for example, Palestine, Syria, and in their particular communities, also in Bangladesh and Pakistan, our two biggest bilateral relationships. Most of those communities have no idea of the expenditure that’s going on in those places. And there’s huge anger, notwithstanding the problems in Syria, if you look at the social media, the anger of those populations was certainly at that time based around what was happening in the occupied territories. They had no idea that we were spending £345 million in the occupied territories.

I felt we could not go on forever with a democratic deficit: spending very large sums of public money without public support for them. I thought that we should go out on the front foot and persuade people that it was in our national interest to spend money in this way and put publicity and effort and enterprise into that. The campaign of which I spoke, the diaspora campaign, was pulled at about Christmas 2014, ostensibly because it would run into the danger of being government advertising too close to a general election. But notably, it never emerged again afterwards. So that was one of my principal concerns and I was never, I think, able to actually reverse that attitude I got.

"I felt we could not go on forever with a democratic deficit: spending very large sums of public money without public support for them."

NH: Including within the Department?

DS: There was no problem in the Department. The problem was elsewhere in government and government’s immediate priorities.

NH: So that was one of your big priorities. From your previous jobs, did you have a sense of what makes a good minister?

DS: I spent two years in the Whips Office, subsequent to being the PPS and also I had spent time in the Whips Office in opposition. And obviously the ministerial performance that you see is in the House of Commons and that is important.

The Commons has changed dramatically over the years, in the sense that the independence of the House of Commons has grown enormously. It started under the Blair years, because his majority was so large they could effectively become their own opposition. Rebellions became much more numerous, because they had the luxury of a large majority. And that’s catching. Equally, when the expenses scandal broke, one of the ways that the Conservative Party sanitised some toxic seats was to ensure that the successor MP was selected on an open primary. Very expensive business, it costs about £70,000 to run it in that way. But nevertheless a significant and increasing number of colleagues have been elected through either fully open primary or some other form of primary. They think, therefore, that they have rather more entitlement to freedom of thought than someone elected purely on the party ticket by a party machine has. And again that is something that is catching. If some people start to behave in that way because they believe they have the democratic right to do so, others catch on. Equally, the amount of patronage available to the Whips Office has diminished dramatically. The most obvious of those being, ‘You keep your nose clean, and you will be on the international development select committee. What’s more you could be chairman of the health select committee, if only you tow the line on this for another couple of months…’ Well, that’s all gone, all of those positions are filled by election now. So increasingly we are at the point where if a minister wants to win a vote, he has to win an argument. That means he’s got to be capable of performing in the House of Commons. I think that remains the most important part of the job: how you actually perform in the House of Commons. Of course behind that there’s all sorts of things you do in a department. So I went into the Department with the focus of a member of the House of Commons, a former Whip, someone who has watched ministers perform very well and some perform not so well.

"I think that remains the most important part of the job: how you actually perform in the House of Commons."

NH: That’s very interesting – before we dig into that a bit more and talk about the day-to-day aspects of the role, you mentioned before that you were on board with the vision of the Secretary of State. How did you work with her and also the wider ministerial team?

DS: The reality is you have been in the House of Commons together so these are colleagues, not superiors. I had spent two weeks with Justine Greening in a place called Rwamagana in Rwanda teaching English to primary school teachers one summer. So I knew her pretty well and there was no difficulty, from the start. Now invariably it would be very different if it is someone you’ve rubbed up the wrong way, like Theresa May, if I found myself in that situation, it would be a completely different thing! Having worked in the Whips Office and having had to deal with and provide tea and sympathy to colleagues who could not bear to work with the leader of their team in opposition, I think these things are much more obvious in opposition. In a ministerial job, you can at least disappear into your office with your private secretaries and at least have some protection from what might be happening upstairs. But in opposition you don’t have that luxury and personalities do have a big impact.

Ines Stelk (IS): Thinking about the day to day reality of being a minister, so your departmental business and your parliamentary role, how did you balance that and spend your time on the different areas?

DS: Well, invariably your ministerial role takes over. Now having left ministerial office, I’m doing a huge amount more in my constituency that I just wouldn’t have done, I would have just ignored. For example, there is a tremendous row going on at the moment between the Forestry Commission and residents of particular areas and other interest groups about the nature of wetland restorations, whether they’re a good thing or a bad thing. Previously I would have simply said ‘This is not a Parliamentary matter.’ Now I get stuck in and make a firm nuisance of myself. So that’s the reality; you spend less time doing constituency stuff because you’ve got ministerial responsibilities. I think the most important person in your ministerial private office is the diary manager. If the diary isn’t working, then the whole thing will go for a ball of chalk. But it is equally important to have a good diary manager in your Parliamentary office, so there is a complete connection between the two and that each understands the priorities and the needs of the other. I think that does make it work very effectively.

"If the diary isn’t working, then the whole thing will go for a ball of chalk."

I did find with being a minister it never finishes; you could spend every hour of every day doing the job. Invariably you will cut corners, just because time isn’t infinite. I found that you do get out of touch with Parliament as well, you need a good parliamentary private secretary. Having been the Prime Minister’s PPS at the 2010 election, I made it my business to know everybody. So, 70 new colleagues come in at the 2010 election, even before the election you’re working on the ones that are probably going to win, you would have learned their faces and a fact about them: you would know all of that. In 2015, being a minister, 70 new colleagues come in and I’m at the other end of Whitehall all day every day, I come down to the Commons in the evening and I have never seen these people before and I have no idea about them. You know, it is important if you regard the management of the House of Commons as an important part of a minister’s responsibility, that you choose colleagues and bring them on-side, particularly when you’ve got a controversial brief in respect of a large amount of expenditure much of which their constituents disapprove of. It is important to manage those relationships. Because you’re separated and not in the Commons nearly so much, you do need to have a very effective parliamentary operation supervised by an effective parliamentary private secretary.

IS: How did you spend your time in the Department?

DS: I spent a great deal of time going and speaking in the City, to business organisations, charities and non-governmental organisations, all of which I think was important and good. The main effort as I saw it in International Development, was that in the end it is all about jobs, it is all about creating the conditions in less developed countries that will generate jobs and economic activity. So a great deal of outreach is to business and to the City and to Lloyd’s of London in particular with respect to insurance and the importance of insurance markets as a growing response to disaster relief. I spent quite a lot of time doing speeches and keynotes in the City, in and around London. Also we do have half the department in East Kilbride. It is very important that they feel part of the deal. Now a lot of it is done by video conference, but I think it was important that every minister should be there for at least one day a month. There were four ministers in the department, so us going up makes it feel much more as if they’re part of the department up there. Balancing all those requirements comes down, in the end, to the diary secretary: you need a very good one and I was very fortunate.

IS: Moving onto crises then. When you had an unexpected event, how did you deal with it? Could you talk us through one occasion?

DS: In my first couple of weeks in office we had the disruption kicking off in Gaza, the last bout, so this would have been July 2014. There was the dreadful business with the Yazidis at Mount Sinjar. And we were just getting Ebola kicking off. Although Ebola had started very, very slowly much earlier in the year, it was suddenly just starting to surface as an issue, we were thinking of what we’re going to do about it, where we’re going to put in a field hospital etc.

"In my first couple of weeks in office we had the disruption kicking off in Gaza… There was the dreadful business with the Yazidis at Mount Sinjar. And we were just getting Ebola kicking off."

I was the minister on duty for those two weeks and it was an extraordinary business with these crises all happening at the same time. The machine is very, very good at dealing with that. There would be Cobra [crisis committee] every day. I remember one of them was on a weekend, all of a sudden they decide we’re going to have a Cobra on a Saturday morning, but I didn’t find out until the Saturday morning! But eventually they managed to get me to a police station in Totton that had the required bat-phone that could be plugged into the Cobra meeting. But I felt actually that crises are fine because the government machine is very good and effective at dealing with them. All of a sudden you find yourself in a Cobra briefing room and you’re surrounded by people who know exactly what has happened and what resources are available to deal with it and how long it will take. It’s very impressive.

IS: So what did you see as your own role in handling the crises?

DS: I certainly went into those Cobra meetings briefed with the issues in my department and the way we wanted to steer it, the way that we thought it would best be handled. So I went in with a whole series of things to raise and draw attention to.

The other great crisis that comes to mind was of course the earthquake in Nepal, that happened actually during the election campaign in 2015. So we were handling it, again, remotely. I remember one Sunday afternoon again having to phone into a Cobra from campaigning in Wales, in what is now the most marginal Tory seat which we never expected to win but did, in Gower. Nevertheless, having to get to a phone that could be punched through to a Cobra meeting was an issue. The huge effort involving the very close relationship between DfID and the Ministry of Defence in both those sets of crises was very, very important. So prior to Cobra meetings, you wanted to be sure you weren’t going to have a spat with Defence. You wanted to make sure that officials had been talking to officials and there wasn’t going to be disagreement.

IS: And how much of it was also dealing with the media?

DS: I have done quite a lot of media since leaving ministerial office, but not much while I was there. I did lots of diaspora media, so I’d do the Bangladeshi press and the Pakistani press and I’d do their TV stations. When I went abroad I’d do lots of media, but it was all local media. I would do quite a lot of diaspora radio here. But I don’t believe I ever did much big media here, whether this was by design to keep me away from it I don’t know!

"I don’t believe I ever did much big media here, whether this was by design to keep me away from it I don’t know!"

There was one extraordinary spat. I remember just as I was leaving the office on a Friday afternoon being given a statement to authorise, which was to be issued to Radio Cornwall for their Sunday morning programme, for which they’d asked for a minister. The Department said nevertheless they weren’t going to get a minister, but here’s the statement that we want to give them. I said ‘Yes, it is fine, it is all true and worthy, but why don’t we just do the programme?’ Gasps of horror! Extraordinary! The exchange of text messages, as I went off on the train, ‘Please reconsider, minister’ and all the rest! And it came down to ‘Well we turn down the Today programme all of the time, what would it look like to them if we say yes to Radio Cornwall!’ Well that’s the key issue: why are we turning down the Radio 4 Today programme? Every time I turned on the radio and heard a comment about DfID, it was from Andrew Mitchell [former International Development Secretary]. They’d clearly asked for a minister, not been able to get one and gone to Andrew Mitchell! So whilst I never did any frontline media, I was never asked. But I am sure they were asking for ministers. Why weren’t we satisfying them? Was it part of what I’ve spoken to already, of this determination not to raise the profile of DfID? Anyway I insisted on doing the Radio Cornwall programme. They were bowled over by the fact that we had bothered. And we got very positive feedback about it, for free.

IS: So you’ve been involved in quite a few different crises, was there any of learning you took from one to the next or do you have any reflections on how to do that?

DS: As I say crises are the easy bits. Because the machine is so effective at dealing with them. What’s difficult is these running sores, of the things you’re trying to keep out of the media like this wretched airport in St Helena, on which no planes can land and the whole business of sexual safeguarding in some of these very small communities. The nonsense of being asked for quarter of a million quid to provide guards for the one prisoner in St Helena who has to be guarded when he should be sent to a prison elsewhere: ‘Oh, we couldn’t possibly do that, human rights law, minister.’ All that sort of nonsense. For example, there was a member of staff who was suing us for constructive dismissal, I can’t remember which particular island it was on. But these things get into the public domain and fill a page of outrageous criticism: ‘£500 million spent by DfID to no effect whatsoever, and here this chap who blows the whistle and look what has happened to him.’ A story quite at variance with the facts. It’s handling those day-to-day things that are much trickier, of course of much less consequence, but they take a disproportionate amount of ministerial time because of the political impact and the questions you’ll get in the Commons, rather than real crises, which we are very effective at dealing with.

What the machine is not good at, to an extent, is political savvy. I think that’s where a minister actually can bring something to the table. I recall I was required to go to the Caribbean and I got the brief and they said ‘Well minister, you’ve got a very tight programme. You’ve got five islands in four days, it is the end of hurricane season, the local airlines are very unreliable. This will only work if you charter a private jet.’ And I said ‘It is bad enough going to the Caribbean, it would be regarded as a jolly, but hiring a private jet takes it over the line.’ They said ‘No, no minister we will write you a letter giving you advice to hire a private jet and then you will be able to say you were only taking advice.’ Well, I had no notion that would satisfy The Daily Mail test, so I insisted on getting scheduled flights. Actually if you looked at the cost comparison, it wasn’t a jet it was just a private aircraft and it was very competitive, but that wouldn’t matter to the story. In the event there was a critical vote and we had to pull the thing anyway, so there it is. Civil servants can sometimes not quite appreciate the political realities. It’s not always the case by any means.

"What the machine is not good at, to an extent, is political savvy. I think that’s where a minister actually can bring something to the table."

NH: Did the Secretary of State’s special advisers help with some of that political savvy?

DS: Special advisers can find themselves very much working for the Secretary of State. I had very few dealings with the special advisers except when I was dealing with particularly sensitive issues and they’d sit in, presumably to report back. But I never had any difficulty with them. I was aware that special advisers were scrutinising all the written parliamentary answers. So the order of business would be that special advisers would have seen the questions and the proposed answers before they came to me. And sometimes there was an issue because a special adviser had not seen the question and there was the answer and we had a deadline to meet and all the rest. I would simply say ‘Actually, it is my answer, I am responsible for it.’

IS: What do you feel was your greatest achievement while in office?

DS: Blimey! Well, I think that the way we handled the debate on the 0.7% spending commitment worked very well. I took the Bill through the Commons – yes it was a Private Members Bill, but nevertheless I had to take it through the Standing Committee and lead on it in Parliament. I would see that as the high point. I am not sure there is any other measurable achievement that I could attribute to myself: it was a collective endeavour.

IS: Another thing we’re quite interested in is how you make policy decisions as a minister. Did you draw on evidence or where there any conversations happening that were particularly useful when you were trying to make a decision?

DS: Invariably, I was asked for all sorts of policy decisions all the time. They always find a way of presenting options to you and effectively you are making a preference sometimes, sometimes not a particularly strong preference, but it was sometimes it was one that that clearly accorded with your own ideological prejudices. It is a difficult thing to think of any big policy decisions that I made.

"I remember driving officials to come up with options and then more options as a consequence of political heat I was feeling."

I remember driving officials to come up with options and then more options as a consequence of political heat I was feeling. For example, we make payments to the Palestinian National Authority. There is a lobby in Parliament which believes we shouldn’t be spending any money on the Palestinian Authority and it’s largely sponsored by organisations that exist in all three political parties that have a radically pro-Israeli stance. They will raise all sorts of questions about the way the Palestinian Authority spends money, principally about paying subsidies, or salaries, to prisoners who are in Israeli jails. So it looks like people are being paid for having been terrorists and being now in jail. Of course, the other side of the coin, the Palestinian Authority says that these are welfare payments for prisoners’ families. When someone goes to prison in Britain, you don’t leave their families to starve. My argument always with the Palestinian Authority was ‘Can we make them look a bit more like welfare payments?’ In other words they should be means-tested and dependant on family size and all the rest. But nevertheless our argument was that we don’t pay prisoners. The UK makes a commitment to a World Bank trust fund which is available for the payment of named civil servants. That list of named civil servants is very heavily and independently audited to ensure that none of our money goes elsewhere, and that was the line that we used to defend. But I continually pushed for, actually a more robust system, to ultimately get to the position where we were paying money directly into the accounts of those civil servants, so we’re actually paying the salaries of health workers and teachers, rather than paying into a trust fund. Yes, we were saying that trust fund is for those salaries, but actually it goes into the same pot as all of the money that the Palestinian Authority has, so you’ve no certainty that your pound went to that teacher. A pound went to that teacher, but was it yours? Because of political pressure, I was driving civil servants to come up with more policy options to deliver what we continued to want to do. It made for a significant amount of work and extra activity, to satisfy a political priority.

IS: And you also mentioned that you went out quite a lot to speak to businesses and outside groups, was the input from outside groups helpful?

DS: Yes. We ran regular roundtables with the legal profession and with big mining firms because of the impact they have in many primary dominated economies. And again the insurance industry was big, they had a lot of input. We were trying to put together some sophisticated financial products and also we have our own investment arm known as CDC, it used to be called the Commonwealth Development Corporation, of course it has expanded well beyond the Commonwealth. I was responsible for that as well, so a lot of financial dealings. Equally my brief included the IFI, the International Financial Institutions, the World Bank principally. That involved quite a lot of liaison with the financial sector.

IS: And lobbying groups?

DS: Well, people come to lobby you all the time. Often enough if you get a letter from a colleague who wants to see you, it’s politic to have them along. It’s often because they have got a firm in their constituency that has bid for work and not had it, and they’re cheesed off. So you have the procurement people in and you point them in the direction of how we go about this and all that sort of thing. Equally we had lobbyists in all the time: I would have the pro-Palestinian lobby in, I’d have the anti-Palestinian lobby in and I would have the groups representing Christians in the Middle East who believed they were being frozen out of aid because of our determination to be secular facing organisation and not to favour any particular group. So you’re dealing with all of these groups, yes.

"Often enough if you get a letter from a colleague who wants to see you, it’s politic to have them along."

IS: And was there anything that they did that influenced you in some ways or might have been useful when you were making decisions?

DS: Sometimes, actually, yes. Sometimes you would think somebody had made a fair point. I can think of one particular lobby. Essentially there are two big organised, capable organisations that are able to delivering de-mining. We had been spending a certain amount on mining for a long time and the problem isn’t diminishing and the advice was we weren’t going to spend any more. I ended up in the position of having been persuaded by the lobby that we actually should spend more on de-mining. But we didn’t do anything about it however, there was a change of government. But that would have been one of the things I would have done as a response to the lobbying I had received.

IS: Was there anything that you found frustrating about being a minister?

DS: I think it was Digby Jones, who was made a trade minister by Gordon Brown when he opened his big tent when he came to power in 2007. After a couple of years when he resigned, Jones said it had been the most dehumanising experience. Now, I enjoyed being a minister and if I’m honest I miss it. However, I do know what he meant, I know what he was referring to. There are enormous frustrations, but they are political frustrations rather than institutional ones. For example, you would be the world’s living expert on some part of your portfolio and you know all about it and what the issues are and all the rest. And all of a sudden you’d discover a decision had been made at a paygrade above yours. What’s more, it wasn’t just that you hadn’t been consulted, you didn’t even know there was a process going on considering this issue! I can remember the bizarre situation of being asked to go and speak to a meeting of Peers and Members of Parliament to sell to them the SDSR [Strategic Defence and Security Review]. The briefing right before I went to address this meeting of parliamentary colleagues from both Houses was the very first I’d had on it! The first briefing I had had at all on the entire question of the SDSR. So there are frustrations.

I suspect even secretaries of state feel those frustrations. I must say, I have attended several National Security Council meetings – we’re a department where there’s a great deal of travel, so if the Secretary of State was away I would substitute for her – and often you would have something sprung on you. Because of the nature of the DfID budget, we would often discover that we’d be paying for something. You would go along and be ambushed and suddenly have a decision sprung upon you, not just in that forum but in others, that would come out of the blue.

"Because of the nature of the DfID budget, we would often discover that we’d be paying for something."

NH: Related to that, how were your dealings with Treasury?

DS: I didn’t actually have many dealings with the Treasury. I think that was handled at the Cabinet level. I had a nervousness about the whole business of shifting a proportion of international development expenditure, they called it Official Development Assistance, ODA, shifting a proportion of that away from DfID to other branches of government. That was very much a Treasury-driven initiative. The whole concept of the prosperity fund, of which I ended up being a co-chairman, was also a Treasury-driven agenda. I was not an enthusiast for that agenda at all and equally I had no input to that process at all. Those issues were all handled at the secretary of state level and I was never consulted about them. Perhaps that’s one of the frustrations.

NH: I just want to touch on a couple of big things that happened politically during this time. So obviously you had election slap bang in the middle of you being a minister, did that change the way you approached the job? Did it change how the department felt before and after?

DS: Having spoken to my private office and other officials, I think they find elections very destabilising and disturbing, the same way that they find reshuffles discombobulating. But I didn’t find any difficulty with the election. They had access to me, I made sure I could come in – actually it was quite nice to have a break from electioneering. It’s all very well if you’re one of the media leads for your political party and you go on a visit to a particular constituency and you meet the big cheeses and you make a few statements. But for most of us, electioneering is knocking on doors all day, irrespective of little signs that say ‘no callers, no canvassers, no purveyors of religious wisdom of any kind!’ So every now and again it was quite nice to have a break and come into the Department and do some work.

NH: And did you know you would be going back into the same job?

DS: I was working on that presumption, yes. There was a little hiccup, in that on the Monday morning when the reshuffle was in full swing after the 2015 election, I wandered into the Department knowing that I was going back there and my pass wouldn’t work in the door, I had to get someone to let me in. I went into my office and they had put everything into a cardboard box on the desk! I turned round and said, ‘Do you know something that I don’t?!’ They all laughed and made light of it and said ‘No, minister this is just what we do when there’s a reshuffle.’ And in jest, in front of them, tweeted: ‘No phone call, card doesn’t work in the door, all my stuff in boxes. Is this the end?’ And this tweet went viral! It was all over the place. So I had to spend the rest of the day in hiding from colleagues who wanted to come and condole with me. It was even quoted in The New York Times as the saddest tweet ever! The Permanent Secretary summoned the Private Secretary and told her she hadn’t done anything wrong, poor girl! She insisted, ‘No, no, I am sure he was joking…’ and she was right.

"I went into my office and they had put everything into a cardboard box on the desk!"

NH: Very good! And you obviously moved from coalition to single party government, did that make a difference to you as a minister?

DS: It did make a difference in that we were a set of ministers who were all from the same party. I can’t put my finger on the difference, but it made it more relaxed, less tense. We worked very well as a department under coalition and certainly I found the coalition as far as the two Whips Offices were concerned worked very well indeed, we got on well. I think I brought that attitude to the Department with me, though there was only one Lib Dem minister. But nevertheless there is a tension. A political party is a wolf-pack and you’re either in it or you’re not.

"A political party is a wolf-pack and you’re either in it or you’re not."

NH: And of course the other big thing was going on was the EU referendum, how did that affect your work as a minister?

DS: Not in the slightest bit. I was the only Brexit minister in the Department. I didn’t campaign overtly in the Department, though I took the occasional tongue-in-cheek opportunity. I remember particularly we had an all staff meeting where you have all the staff together and it is video-linked to the East Kilbride office and indeed to our posts overseas. There was a campaign being run by The Daily Mail to abandon the 0.7% commitment and they’d got 1 million signatures on a petition, so they’d gone over the threshold required to spring a parliamentary debate, which is 100,000. There were 1 million signatures saying we should hang this commitment. I took this opportunity to point out there was not the remotest possibility of us abandoning this commitment, I said that this was effectively our leadership in the international community on this very important issue and let me assure you when Britain lead others will follow: Britain leads and that might be something you care to remember on 23 June! I think that was as far as I got within campaigning within the Department. Nick Hurd spoke immediately afterwards and of course called me shameless! It was treated in a light-hearted way.

In terms of the restrictions that the Head of the Civil Service had issued for dealing with ministers who were in the Brexit camp – not providing certain assistance and all the rest of it – that didn’t affect me in any way. The Secretary of State said to me if there were any problems to let her know, as did the Permanent Secretary, who came in and saw me and said ‘Look if there is any issue come straight to me’, but there never was an issue. Notwithstanding we had a department that spends a significant amount of money through the EU. We have 16 staff in DfID working on that relationship and 26 in Brussels, DfID employees trying to bend them to our agenda. That part of the portfolio fell within my remit. But I never ever had any difficulty at all. I did campaign vigorously. I think I did 15 or 16 public meetings, several public debates, two against Vince Cable. I didn’t hold back on Brexit, but I didn’t find it affected my ministerial work at all.

"I didn’t hold back on Brexit, but I didn’t find it affected my ministerial work at all."

NH: Finally, what would be the top tips would you give to a new minister on how to be effective in office?

DS: You’ve got to be good in the House of Commons, that’s the first thing. You’ve got to work on that. If you can’t perform at the dispatch box, you’re not going to perform.

"If you can’t perform at the dispatch box, you’re not going to perform"

The other tip I would say is make sure you’re absolutely comfortable with your private office. In particular, the most important thing in your private office is making sure that the relationship between your diary manager and other diary managers elsewhere works well. The diary manager is the most important thing. Because there is nothing more frustrating, if that doesn’t work. I was very fortunate, I never had a problem, but I could see that was the critical area.

- Keywords

- Foreign affairs International development

- Political party

- Conservative

- Administration

- Cameron government

- Department

- Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Legislature

- House of Commons

- Public figures

- David Cameron

- Publisher

- Institute for Government