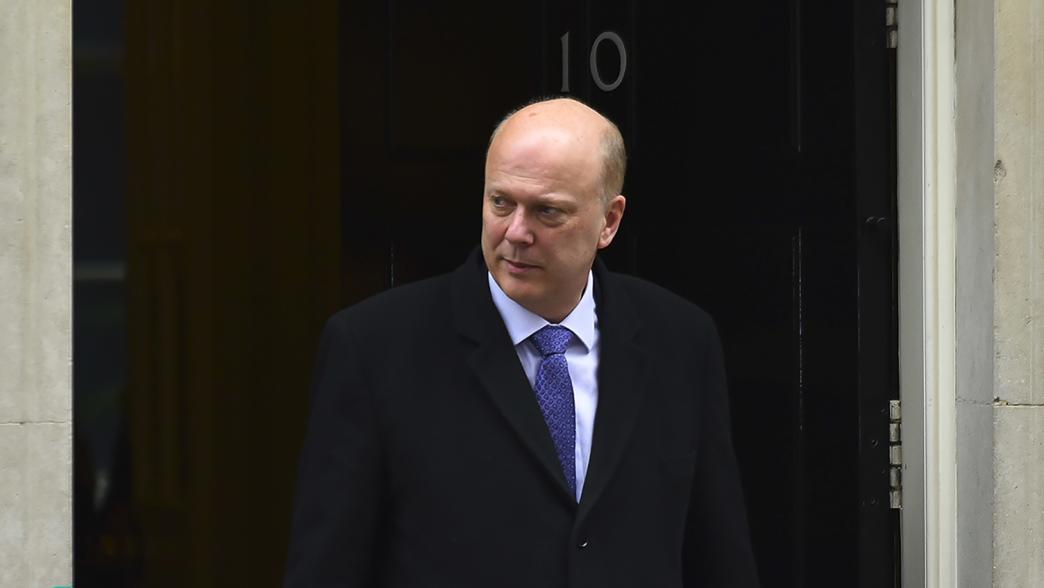

Chris Grayling

Chris Grayling talks about his various ministerial roles, including key decisions he made as justice and transport secretary.

Chris Grayling was secretary of state for justice (2012–15), leader of the House of Commons (2015–16) and secretary of state for transport (2016–19). He was also minister for employment (2010–12). He has been the Conservative MP for Epsom and Ewell since 2001.

Tim Durrant (TD): After the 2010 election, you entered government and became a minister of state at DWP [Department for Work and Pensions]. What was your first day of becoming a minister like, and what was the conversation you had with the prime minister?

Chris Grayling (CG): Well, it was strange, because I had been, I think, lined up to do a different job in government had we won the election outright. I know that I would have been elsewhere in the cabinet, but I went back to DWP because David Cameron knew I’d done it previously. For political reasons he’d brought in IDS [Iain Duncan Smith, former secretary of state for work and pensions] to head the department, but he sent me back in, saying, “we now want you to pick up the work you did previously in the shadow role.” So, it was a strange one because I was disappointed not to be in the cabinet, but pleasantly surprised to discover we were sustainably in government. I had been doubtful about the coalition before it was set up, but actually from the very start it seemed to work quite well, and relations between us and our Liberal Democrats counterparts were very good. Steve Webb was my next-door neighbour in the Department for Work and Pensions, and we got on very well from moment one.

TD: Did David Cameron give you any guidance on the specifics of your portfolio or the priorities he wanted you to work on?

CG: Not really. I mean, he basically just said to me, “IDS is coming back to head the department and I want you to play a very active role in keeping it ticking over,” but he didn’t give me any specific remits. And I’d done stuff in opposition on employment, so he wanted to pick up the work that I’d done on those matters.

TD: Was that helpful, knowing the issues?

CG: Totally yeah, it was basically putting in place what I’d designed two and a half years earlier, so yes it was very much picking up where I left off. Once I’d worked that out, I found I was doing this job where actually I knew exactly what we were going to do.

TD: And how did the department work? How did the team of ministers work together?

CG: It was very good. IDS was very, very focused on delivering Universal Credit and basically left me to do employment almost untouched. I mean, not totally, but basically I did employment and he did welfare and social security reform. We worked pretty well together. The permanent secretary, Leigh Lewis, was very welcoming, very open, so relations across the ministerial team were very good. And David Freud came back in to be Lords minister. David and I worked closely together on developing employment programmes, but David did more on Universal Credit than he did on employment programmes. But no, it was a very good working team from day one.

TD: How did you find support from the civil servants?

CG: I had a great team of civil servants at DWP, and I have really got no complaints. Over the years, there’s been the odd individual who I didn’t think was very good, but basically I’ve never had any real complaints about the civil service teams who’ve worked with me. I’ve worked very closely with them, got on very well. The private office teams I’ve had were very professional and most – not all – of the people who worked with me in other departments have been very good.

TD: One of the interesting things about the DWP is they have a big nationwide presence, they’re not all based in London. Did you travel around much in that job, going to different offices?

CG: Yeah, all the jobs I’ve done I’ve travelled around a lot. With DWP, I sat in Jobcentres, I sat going through interviews, I sat alongside decision makers as they phoned people up to tell them what the decisions were about their benefits applications. With [the Department for] Transport, I’ve been all over the place, and at [the Ministry of] Justice, I was all over the place. I visited about a quarter to a third of the prison network when I was in justice. So, I’ve always gone around and about, trying to talk to people on the product line, to find out what’s happening.

TD: You worked in a number of roles in the shadow cabinet before the 2010 election. Did they inform your time in government?

CG: Yeah, basically the jobs I did in government and the jobs I did in opposition married up almost totally. I was in the Home Office rather than in justice, but basically the jobs I’ve done in government have been the jobs I did in opposition, so there’s been a very close correlation. In none of them have I turned up as a total stranger.

Nick Davies [ND]: In September 2012, you became secretary of state for justice and lord chancellor. Can you talk us through the appointment process, the conversation you had with the prime minister, whether it was something you were expecting?

CG: I thought it was quite a good possibility because there was a lot of commonality with the reforms I’d been talking about [at DWP]. The coalition agreement envisaged a fairly similar approach in employment and in the rehabilitation of offenders. I had not been involved in shaping the justice piece in opposition, but I had been involved in shaping the work and pensions piece in opposition, so there was an obvious correlation between the work I’d been doing in DWP and the work David Cameron asked me to do in justice. And David Cameron gave the standard, you know, “come along, see the prime minister,” and he said, “I’d like you to go to justice.” He gave me two instructions, he said, “firstly, I want you to deliver the rehabilitation revolution commitment in the coalition agreement,” because his view was that it hadn’t really been delivered. Both the Conservative manifesto and the coalition agreement envisaged a significant outsourcing of the rehabilitation of offenders. And he also said, “I want you to get rid of the soft justice narrative,” which had been quite visible in the previous couple of years.

ND: What lessons did you take from overseeing the work programme to the implementation of TR [transforming rehabilitation]?

CG: I think the big difference between the two, both big reforms, both requiring a little bit of tweaking once they got up and running, is that in the case of the DWP, the team who had set up the work programme were still there. Whereas in 2015, pretty much everybody who had been involved in the transforming rehabilitation programme left. The ministers all left, the senior officials all left, and it did not get the tweaking and fine-tuning that it needed. In both cases, in the case of the DWP and the MoJ [Ministry of Justice], the statisticians got their numbers wrong. They misjudged the number of referrals that the third-party contractors would get. In the case of the DWP, they were able to make early adjustments to the contracting structure to make sure that wasn’t an issue, and by the time the programme finished, an analysis in 2016 said it had outperformed the expectations of the department based on previous programmes, and at a lower cost than previous programmes. With transforming rehabilitation, from what I could see, they sat there like rabbits in the headlights, saying: “Well, I don’t quite know what we do about this.” The referrals were much lower than expected to the outsourced companies, whose business models then were fatally weakened from the start, and they didn’t make the adjustments they needed to make earlier on.

"The ministers all left, the senior officials all left, and it did not get the tweaking and fine-tuning that it needed."

ND: Knowing what you know now, is there anything that you would do differently to avoid some of those problems?

CG: Yeah. I think, with hindsight, it’s an interesting problem. Arriving halfway through a parliament with a mandate to deliver major reform sets you, to some extent, a timetable. You might think two years and nine months was more than enough to deliver reforms, and in most worlds it would be. But the public sector moves pretty slowly and there’s huge amounts of process involved. I would probably have done it in stages, I wouldn’t have just done one pilot in one part of the country. Because for transforming rehabilitation there had been a pilot in Peterborough of outsourcing the support of offenders to the private and voluntary sectors, which had a measurable impact on the level of re-offending. But I’d probably have done it in two or three stages.

ND: What was the advice from the civil service like on the programme?

CG: Oh, they were very hard working on it. There is a myth floating around that the civil service advised against it, which is not true. The civil service, at all stages, was very, very engaged in delivering it.

ND: More generally, what are the key challenges entailed by taking the step up from minister of state to secretary of state, and what was the support like for you from the civil service when you moved up?

CG: Pretty good. I think the key difference is you suddenly take on financial responsibility in a way that you don’t necessarily as minister of state. The financial position at the Ministry of Justice was very challenging. We had to take out something like a third of the budget over a three-year period. That was implementing reforms that Ken Clarke [the previous secretary of state for justice] had legislated for but not done, so most of the cuts in legal aid had been legislated for before I arrived but came into force on my watch. So, the budget pressures were enormous. Actually, one of the great hidden facts about probation is that the probation reforms insulated the probation service from what would have been significant budget cuts, because we were looking to expand the remit of the probation service to incorporate all the short-sentence prisoners. The Treasury did not insist on significant cuts in the way they did with the prison service, legal aid and the courts. So, I think the dominant feature of my time as secretary of state for justice was huge budget pressures. One of the great ironies, which wasn’t spotted at the time, was that because Michael Gove [Grayling’s successor as secretary of state for justice] was due to be George Osborne’s campaign manager in his leadership bid, when Michael took over as secretary of state the department’s budget went up by £500m, which took away a lot of the budget pressures we’d been dealing with in the last 12 months.

ND: Given those pressures, what was your approach like in managing a team of ministers and how did you go about identifying priorities for the department and the team?

CG: Well, the first thing I did was decide to not privatise the prisons. What I inherited from Ken Clarke was a rolling programme of prison privatisation but, looking at the plan, it was very clear to me that whilst it theoretically delivered savings, those didn’t arrive until the mid-2020s, which wasn’t a lot of use for us back then. I had bids from the private sector, but I also had a counterbid from the in-house team, from prison governors and prison unions, to run the prison service according to a different template. They took what they saw as best practice from across the estate and applied it to the prisons that were in line for privatisation, saying: “We can deliver for you.” The savings were smaller, but they were more immediate. So, the decision I took was to stop the privatisation process of the prisons but to say to the governors, “what I need you to do is to put in place the benchmarking that you’re talking about for these prisons more broadly across the estate, because that’s the only way I can meet the financial targets without really driving aggressive privatisation,” which I didn’t think was right.

ND: You mentioned the injection of cash the department received under Michael Gove. Can you describe what relations were like between you and Number 10, and the Treasury, during the time you were at MoJ?

CG: Generally, pretty good. Probation reform, as far as Number 10 and the Cabinet Office were concerned, was a priority. I mean, Nick Clegg described it in one cabinet meeting as one of the most important reforms the coalition was doing. This was a fairly fundamental part of the coalition agreement, the rehabilitation revolution, and so Number 10 was always very keen and positive about it. The Treasury was fine and helpful but process; everything takes a very long time.

"I don’t believe great bust-ups in Whitehall help. Understand where they’re coming from, have good relations with the other ministers."

TD: What would your advice be for ministers dealing with those two parts of government, the Treasury and Number 10?

CG: Try and remain friendly with everyone. I don’t believe great bust-ups in Whitehall help. Understand where they’re coming from, have good relations with the other ministers. Although it does annoy the civil service sometimes when ministers phone each other up and agree things without the civil service being present! But just maintain good relations all around, would be my best advice.

TD: You mentioned earlier you’d visited a large proportion of the prison estate. What can you take from those visits as a minister, how does it inform your decision making in Whitehall?

CG: Well, what it does is it shows you the reality of life on the ground. For example, you are always dealing with accusations that the prison estate is overcrowded. I mean, in all the briefs I’ve had there’s usually a relentless attack from the left, who want the world to look very different. If you’ve done a walk around the prisons to see what it’s like and you’re told the prisons are hideously overcrowded, well yes, it is true that we did not provide a single cell for every prisoner, but it would have been impossible to do so. So, the question is, are we putting people in completely inhuman conditions, given these are prisons? And most of the estate was, in my judgement, sufficiently okay to be justifiable. Some of the older estate improved very little. In fact, I closed more prisons than any other justice secretary has ever done, or home secretary has ever done, and some of the ones I closed were a problem. There was one on the Isle of Wight in particular that I went around and thought: “I’m glad I’ve closed this because it’s not fit for use as a prison.”

ND: After the 2015 election, you were appointed as leader of the House of Commons. Again, can you talk us through the appointment process and your expectations around that move?

CG: David Cameron gave me a ring on the Saturday to go and see him and he said to me, “I’d like you to become leader of the House, I’d like you to introduce English votes for English laws.” He was very clear that while it had been an outside cabinet position previously when Andrew Lansley was doing it, he said this time no, this was a serious cabinet position. It was ranked sixth or seventh in the cabinet, so it was very intentionally not designed to be a demotion, and off I went. Much of that summer was spent trying to sort out the introduction of English votes for English laws in the Commons, which was quite controversial with the Scots but reasonably warmly welcomed otherwise. Or it certainly was on our side. Labour would have always opposed it anyway. And then after that, we rapidly moved into the referendum period.

The other thing I did, which took up lots of my time, was the restoration and renewal programme where the leader of the [House of] Lords and I co-chaired the committee that effectively paved the way for setting up the current structure to take the project forward. So, that and English votes for English laws were the two things that took up most of my time.

ND: What was it like being leader of the House during the period of the referendum process?

CG: It was a strange period, because you were both in government and opposition simultaneously, which is almost a unique experience for any generation of politicians. I tried all the way through to remain on good and friendly terms with Number 10. History shows there have been some fractured relationships, but I made a point of trying to be collaborative with Number 10, to argue the case [for Leave] but, for example, if I was doing a major interview I’d phone and let them know so it wasn’t a surprise. I talked to David Cameron from time to time during the campaign, trying to make sure it didn’t degenerate from my point of view into ruptured relations, which is what I didn’t want. The rest of the time, apart from on Europe, I felt we were all on the same side.

ND: Did your time as leader [of the House of Commons] change how you approached parliament in the other roles that you then subsequently had?

CG: I don’t think so particularly. Because actually, with a departmental brief, depending on which one it is, you can spend a lot less time in the chamber than you would do otherwise. I mean, there’s questions and periodic debates and interviews, and some ministers are in all the time. But certainly, at Transport, that wasn’t really the case.

ND: After the referendum, Theresa May became PM and you were appointed secretary of state for transport. Did she take a different approach to appointments to David Cameron?

CG: It was very similar. The standard routine is Number 10 calls up and says, “can you come and see the prime minister at such and such a time?” and the prime minister gets you in the Cabinet room and says, “I’d like you to do X.” And that was exactly the same for me.

TD: Was there any more guidance on specific responsibilities or portfolios or priorities from the PM?

CG: She said to me, “I support HS2 and I’d like to back it.” She said to me, “I want you to sort out Heathrow,” or rather sort out airport expansion. I was very focused on that, and for me it was the most important thing I did as transport secretary. I would argue, if it all comes to fruition, the most important thing I achieved in government is getting the expansion of airport capacity and the expansion of Heathrow airport to the stage it is at now. I believe it is fundamentally important for the country.

ND: HS2 and Heathrow expansion were both huge policies that received quite vocal opposition, including from members of your own party. Can you tell us how you negotiated the process for those?

CG: Well, I think, with Heathrow, we have been enormously careful. When I took over, I genuinely looked very carefully at all three options that the Airports Commission had recommended during the summer. I went and spent time with each of the three bid teams, each of the three sites, looked at them very carefully, understood what was going to happen. And actually, each of the proposals had their own strengths, so it wasn’t by any means a slam dunk that Heathrow would go ahead with the north-west runway. Alongside that, it was obvious that this would end up in court. But I and the officials spent a huge amount of time really trying to make sure we’d got the detail right, because this was always going to be difficult. I mean, we’ve won the first couple of cases comfortably, we’ve won on every count, but of course it has to go through the Court of Appeal, and it will go to the Supreme Court in the end. But we have done everything we possibly can to make sure we covered the bases, and I took great comfort from the first round of court cases, as well as the majority in the House [of Commons], that we’d done the work properly.

ND: These kinds of big infrastructure projects have benefits for the whole country, but they can be quite a blight for a small number of people in specific geographic areas. How do you think ministers can work to involve the public on big infrastructure decisions like this?

CG: Well, of course, in the case of HS2, Phase 1 was already effectively in place because it had been through parliament, it had been through the hybrid bill process. We’d been doing the hybrid bill for a short section between the Trent Valley and Crewe, which clearly had local impact, but not anything like on the scale of Phase 1 or Phase 2b will have. So, I guess I didn’t really get the full force of the debate that had happened with Phase 1, before it came to parliament. But I think my instructions on HS2 were, firstly, treat people decently. I didn’t want to end up with lots of court cases, that would be completely wrong, so I wanted people treated fairly.

As a ministerial team, we sought to intervene in specific cases where people were hard done by, so in a number of cases we intervened to say, “no, you’ve got to do a better job on the compensation front,” where there were particular local circumstances. For example, on the Shimmer Estate, which is a new estate in South Yorkshire which HS2, sod’s law, goes straight through the middle of, if you owned a house on that estate that was going to be affected by HS2, you could not at that time buy a comparable house in the same area for the same price. And I said you’ve got to make it possible for people to get a similar house down the road in the same area, it’s not fair otherwise. So, we took an active involvement in trying to shape sensible rules to look after people. But there’s no way you can do any big infrastructure project without it affecting some people, so the guidance was just to be as fair as possible to people.

ND: The Department for Transport (DfT) also had few high-profile issues while you were there, such as timetabling and the re-nationalisation of the East Coast Main Line. How do you think ministers can deal with crises well?

CG: To take those in turn, the East Coast Main Line had been building up for months. It was, I have to say, completely infuriating. That contract should never, ever have been accepted. The East Coast franchise had collapsed twice before, and if I’d been secretary of state, I would never have accepted a bold and ambitious bid for it because I just simply would not have believed it. So, I was dealing with a situation that wasn’t of my making, where it was quite clear where it was going to end up. You can’t close down a contract until it’s reached a point where it has actually defaulted, but you could see what was going to come. I took the view that you couldn’t just carry on with more of the same. It was impossible just to re-let the franchise, which is why we moved to a partnership structure for it and why, in the end, I judged it was better to bring it back into public control. It was important not just to bring it back into public control and to say “nationalise the franchise”, but actually to try and shape a joined-up partnership working between the Network Rail team and the train company teams.

On the timetable issue, it came, from the point of view of ministers, completely out of the blue. We’d had reassurances over months that it would be fine, there had been no alarm bells raised. I had in the case of Thameslink, the leadership of that company and the two leaders of the separate bodies we’d set up to monitor progress towards the new timetable in my office three weeks before saying, “‘it might be a slightly shaky start, but it will be fine.” One of the challenges of the Department for Transport is that while it sits at the top of the pyramid it doesn’t have any of the controls and levers over the way the industry works. So, you have professionals who run it, rail professionals, who tell you when it’s working and when it’s not. But there was no inkling among senior people in the department or ministers in the run-up to the timetable issue that it was going to be a problem. Indeed, the Glaister Review into it said that they didn’t find a smoking gun, something that had been ignored in the department, at all. So, the failing in the department, and indeed in the Office of Rail and Road, if there was one, was not actually asking difficult enough questions, and taking it at face value what the industry was saying.

ND: What advice would you have for future ministers about how to surface potential risks like that earlier?

CG: Well, that’s a very good question, because we had an industry readiness board and we had an independent assurance panel, both chaired by senior respected figures in the industry, who just got it wrong, didn’t see it coming. My own view is if there was culpability, really it was within Network Rail. Network Rail is the guardian of rail timetables. And what Andrew Haines, the new chief exec of Network Rail, has done very well is he has taken much more personal control over major changes like that. He’s put in place high-level, board-level industry bodies to oversee timetable changes. The industry does timetable changes every six months. In my time as secretary of state, there were six timetable changes, five of which nobody ever noticed. One went horribly wrong, and of course you get loads and loads of noise when the one goes horribly wrong. The big lesson of the timetable change is the big flaw of the railways, which is that nobody’s really in charge. It cannot and should not be run by ministers or by the Department for Transport, and I hope out of the Williams Review [into the future of the railways] we’re going to get a proper strategy to oversee the industry.

TD: Given that it is the responsibility of the private sector and the rail companies to actually run the trains, in that instance what do you think the role of the secretary of state is?

CG: My view is that the role of the secretary of state is to decide how best to spend public money. The secretary of state for transport has never been involved in running the railways in detail, and never should be. The department gets involved in much too much detail. It’s one thing to say: “‘Right, I’m going to spend a billion pounds on this project, what are you going to do with the money?” It shouldn’t be down to people in the Department for Transport to be keeping a weather eye over the training of train drivers. The reason that GTR [Govia Thameslink Railway] had the problems is because they messed up the training of train drivers. It cannot be for the government or political arena to be micromanaging to that degree.

"The big lesson of the timetable change is the big flaw of the railways, which is that nobody’s really in charge."

ND: Given that much of modern government involves either the role of arm’s-length bodies or private or voluntary sector organisations delivering services, do you think that we’ve got the right kind of set-up for ministerial accountability?

CG: Well, the truth is that if something goes wrong it will always be the responsibility of the secretary of state and if things go smoothly nobody will ever notice. It’s just a reality of government, I’m afraid, that ministers are blamed for things that are completely out of their control because they sit on the top of the pyramid. That’s the nature of politics, I’m afraid.

ND: How did preparing for Brexit at DfT work in practice?

CG: Notwithstanding one joy, we were probably the best prepared department in Whitehall. We sorted out all the international agreements we needed, we had put in place structures to manage the process of a no-deal Brexit; we had informally had discussions about bilateral agreements, if they were necessary; we had had informal discussions with officials in the [European] Commission. The Commission put in place a structure at their end which we then mirrored that would have ensured the flow of transport. If we had left with no deal in March [2019], with the exception of the pressures at Calais and the Channel Tunnel, we were in pretty good shape.

The controversies were caused around the work that we did, ironically, not for ourselves but to help the Department of Health [and Social Care] by sorting out ferry capacity for them. The media got dramatically excited over what was a complete non-story. We had given a contract to a small ferry company that was being set up, for which we were due to pay no money unless they ran the service. It was a kind of back-up, because we had the capacity we needed from two established firms. We gave a contract to the third firm as a back-up because, although they were a new firm, although we knew that they were only part-way to establishing their business, there was no downside because we weren’t going to pay them any money unless they were actually operating a service. But the media got terribly, terribly excited about it.

"At that time, the Treasury was being profoundly unhelpful in terms of no-deal preparations."

We then had the joy of Eurotunnel taking us to court. That happened, I would say, purely because the Treasury delayed and delayed and delayed the decision making until we were exposed to legal risk. It was a big frustration that the Treasury was not a helpful force, in stark contrast to now, when the Treasury has really engaged in Brexit. At that time, the Treasury was being profoundly unhelpful in terms of no-deal preparations. We recommended as a department that we could sort out capacity to ease pressures for essential goods to get into the country in early to mid-October last year, but said we would have to get it sorted out by the middle of November in order to have the capacity definitely in place, because from that point on capacity starts to be contracted out for the following summer elsewhere. So, one of the ships we might have contracted, for example, by the time we actually started the process, had gone off to the Canaries and was booked for the summer. So, I’m afraid the Treasury delayed and delayed and delayed to the point where not only did we not actually have all the options we’d expected, but actually we ended up at the point where we had to take legal risk. We warned them there was going to be a legal risk, but we didn’t expect the legal risk to materialise before Brexit because normal court timetables meant that if anybody had sued us it would have taken them 12 months. In the event, a judge decided it was in the public interest to accelerate the case. But it was very frustrating. I don’t do slagging off parliamentary colleagues and other departments, but I’m afraid that the challenge we had over the legality of the contracting process was caused by undue process and a lack of listening to warnings in the Treasury.

ND: How did you manage your relations with the transport sector during that process?

CG: I met senior people in the transport sector all the time. I had regular relations with them and still do, having left.

ND: And you were happy with the advice that you received from your department?

CG: Yeah, I mean, looking back, what could or should the department have done differently? Well, it should never have given the Virgin Trains East Coast contract, it was always wildly ambitious. And indeed, we tightened up the process, although there was only one franchise which I handled start to finish, which was the East Midlands one. But we tightened up the franchise process before we moved into the Williams Review. I think the challenge the Department for Transport has is that there are perhaps too many people who are too close to their mode of transport, if that makes sense. They perhaps don’t always take a step back and look at this as dispassionately as they might. A lot of people there have their own ideas about how to do things because they have a particular interest in their mode of transport.

ND: You held your roles in the Department for Transport and in the Ministry for Justice for around three years each, which is a relatively long time for ministers. What impact do you think longevity has on the approach ministers take and on ministerial performance?

CG: I think three years is probably about right. The only issue is that it is much better, if there are major reforms, that the same minister sees them through. Chopping and changing mid-reform is not good, as witnessed by transforming rehabilitation. If I’d been there for one more year, I would have seen very quickly that the referral numbers were not right, and we would gone back and revisited the way it was being done. And that didn’t happen. And the frustrating thing is, in the early days, reoffending rates came down and there were some good stories to tell, but quite clearly the finances of the providers were squeezed much too heavily and they were losing money all the way through.

TD: Were the same people in the same junior ministerial roles throughout your tenure as secretary of state at those two departments, or did they change more quickly?

CG: They changed more often. With justice, the Lib Dem minister changed once, the minister of state changed once. I think probably in each department, I had a full change each year.

TD: What impact does that have?

CG: Well, it’s helpful having people who’ve got more experience, so with transport in the end Andrew Jones [then parliamentary under secretary of state at DfT] came back having been there at the start. Having someone experienced is very useful.

TD: How did the different parliamentary set-ups of the governments you served in [coalition, majority and minority] affect the role of the minister?

CG: The coalition government, although I arrived as a sceptic at the start, worked pretty well. Ultimately, almost all the time we had a majority of 70 or 80. The Lib Dems were an interesting check and balance on us because there were some things they would not let us do, but there was never anything I tried to do that the Lib Dems tried to stop me from doing. We modified a few things, but actually it was a team effort all the way through. In justice, I had really good relations with my two Lib Dem ministers, Tom McNally and Simon Hughes [ministers of state for justice 2010–13 and 2013–15 respectively]. We did everything together. They added value, to be honest.

As for the majority, 2015–17 was all very much, in the end, dominated by Brexit. It’s been much more difficult politically for us since 2017, but I don’t think the balance in parliament ever made life particularly difficult for me in the transport job. Issues might have done, but the numbers didn’t particularly.

TD: How did Brexit change the way that the government functioned?

CG: I think it meant, certainly since 2017, that it was difficult to do a lot else. But I must say, in my role in transport, there was nothing that I wanted to do that I wasn’t able to do because of Brexit. We did, on a number of occasions, sit down with the departmental board and go through and streamline the things that we were doing, but we didn’t get rid of anything that was mission critical, we got rid of things that were really not necessary. We would go through a list of things the department was doing and say, “why are we doing this? Do we really have to?” So, an example would be moving the MOT from three years to four years, which has a negative impact on local garages. Yes, it saves the consumer money, but right now, in the middle of doing Brexit, do we really need to do that?

TD: Did ministers view their relationships with each other through Brexit as well, or did normal business continue for government business as a whole?

CG: Normal business continued, but I think you would say that, if you’d sat in the cabinet from 2012 to 2015, cabinet meetings have been more lively. I mean, cabinet meetings are generally fairly routine discussions, you don’t generally get tense discussions in cabinet, it’s much more about reviewing and discussing the programme going forward. It’s been livelier post-referendum, but it’s not like everybody was at each other’s throat and shouting at each other all the time, as reading the papers might have you believe. It’s not like that.

ND: Can you describe the process of leaving the government in the 2019 reshuffle?

CG: I had decided nearly 12 months ago that after 17 years on the frontbench, time had come for a change, and I’d told Boris [Johnson] and Theresa [May] that. I’d told Boris that I definitely did not want to stay in transport, three years was long enough, and was kind of open to doing something else but not particularly desirous of doing something else. And he just called me down and said: “This is time to make a change, so thank you very much.” And I said: “That’s absolutely fine, because I am quite happy about that.”

ND: Could you reflect a bit more on the achievements you’re most proud of from your time in office?

CG: The most successful reform was the Work Programme and the employment programmes that went alongside it. An independent appraisal in 2015 said that the programme had delivered higher than expected outcomes at a lower cost than previous programmes. And most importantly, it had helped hundreds of thousands of long-term unemployed people back into sustainable employment. In addition, the Work Experience Scheme, which gave young people the opportunity to gain access to the workplace without losing their benefits, helped a very large number of them onto the employment ladder.

The thing that I think will have a lasting impact, as long as we can see it through now, is the expansion of Heathrow. I took a completely dispassionate view to the assessment, went through it very carefully, and Heathrow won the argument. Nonetheless, I passionately believed we needed to do this, we needed to expand the capacity of the south-east. And I am very committed to delivering that, so I think that’s the most lasting achievement. When I look back on my time in government, if that runway makes it through and opens, then I will believe that’s the most important thing I did. As of today, I and this government have got this project further than it’s ever been at any point in the last 50 years. That’s the biggest and most important thing. Perhaps the most unexpected and rewarding thing was pardoning Alan Turing, because although the Queen did it, she did it on my recommendation. What happened to him was a complete travesty in our history, so it was very nice to be able to do a little bit to rectify that.

ND: Final question, what advice would you give to a new minister on how to be most effective in office?

CG: I think the decision you have to take as a minister is do I want to do things, do I want to be positive, do I want to have an impact? And what I’ve learnt in the last nine years is that if you do try and deliver change, real change, sometimes you will get criticised for it. If it works, then probably you’ll get little credit for that. If it runs into problems, you’ll get criticised. You have to decide: “Do I want to try and make a difference to some of the problems that lie in front of us, that sometimes seem intractable, or not?” It’s easy to turn up and be a minister, to just sit there letting things tick over, but that’s not why I went into government. I went into government to try and make a difference, and sometimes that works and sometimes it doesn’t.

- Topic

- Ministers

- Political party

- Conservative

- Administration

- Cameron-Clegg coalition government Cameron government May government

- Department

- Department for Work and Pensions Ministry of Justice Department for Transport Office of the Leader of the House of Commons

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Legislature

- House of Commons

- Publisher

- Institute for Government