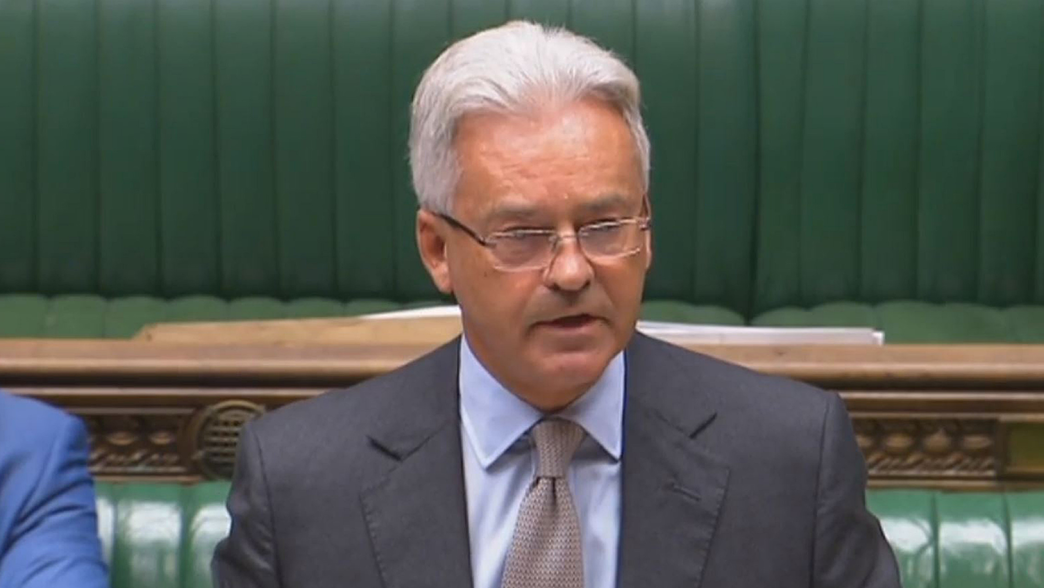

Alan Duncan

Alan Duncan was interviewed on 30 June 2015 for the Institute for Government’s Ministers Reflect project.

Sir Alan Duncan served as minister of state for international development between 2010 and 2014. He was the Conservative MP for Rutland and Melton between 1992 and 2019.

Duncan also served as a Foreign Office minister (2016–19) after this interview took place.

Jen Gold (JG): Thinking back to when you first started as a minister, what was your experience of coming into government like?

Alan Duncan (AD): It was a complete change of gear because it was a coalition government replacing a Labour government. So I suppose 95% of the ministers were new and had not been a minister before. You get no tuition in how to be a minister and I think it means that some are good at it and quite a lot are not.

The real issue is to understand and strike a balance in the relationship between what you think your power and authority is compared with that of your officials. That is the key point about being a minister – what is the dividing line between you telling them what to do and them telling you what to do? That is the key point.

Catherine Haddon (CH): And were there moments in those early days where it was difficult to turn that into reality?

AD: The key to this is the private office. You need to find a private office who have integrity and confidence but also initiative. A minister can be deeply hamstrung by a formula rules-driven private secretary who has no imagination.

A minister can be deeply hamstrung by a formula rules-driven private secretary who has no imagination

JG: You mentioned getting no tuition on being a minister, but what kind of support was available to you?

AD: In what sense?

JG: In terms of briefing, mentoring…

AD: Oh no, ridiculous idea, of course not, we are individuals. No, none whatsoever and nor should there be. What there should be, however, is a proper sort of guidelines, if you like, about your powers to hire and fire, your powers to instruct and demand, or certain things that you can’t do. And there is far too much pressure on ministers from officials trying to say that there are certain things they cannot do. Officialdom has become far too haughty and self-important. The first permanent secretary I had clearly thought she was far more important than ministers.

JG: And how had your previous roles and experience prepared you for the role? You had obviously had shadow ministerial positions before coming into the Department for International Development [DfID].

AD: Oh, I think shadow ministerial jobs are of almost no use whatsoever in training you to be a minister because the quality of briefing is minimal and you are not really running anything, you are not running a department, all you are doing is posturing and issuing press releases and trying to win an election. What trains you to be a minister is having done something outside politics first, in actually running something.

What trains you to be a minister is having done something outside politics first, in actually running something

JG: So your background in the oil sector?

AD: Yes, much more interesting.

JG: And in what sense did that help you?

AD: Sense of corporate structure, lines of command, if you like. But that said if you get the right private office it makes all the difference as did in my case the relationship that the minister of state has with his secretary of state.

CH: In what ways did that help you?

AD: Because secretaries of state can get very bossy and say you can and cannot do certain things. ‘Yes, you can go on that trip’, ‘No, you can’t and that responsibility is mine’, ‘You are not allowed to talk to Number 10’, ‘I am going to see the Prime Minister’, all that kind of stuff. And a good secretary of state will bring out the best in their ministers and enjoy their success. A poor one will be a control freak who tries to hog everything for themself and in the end they are resented, of course.

…a good secretary of state will bring out the best in their ministers and enjoy their success. A poor one will be a control freak who tries to hog everything

JG: You served under two different secretaries of state. How did you go about forming effective working relationships with them?

AD: Just abundant reserves of charm [laughter]. I mean in my case, the most important thing I did was to be successful in my negotiations with the Secretary of State on day one in carving up the globe. I was in DfID, I did not want to do Africa. Normally the number two in DfID does Africa. It would have driven me mental. So I got the bits I wanted, which were the Middle East, Palestinian Authority, Yemen, Bangladesh, Burma, Nepal and the Overseas Territories. I ended up with a great swathe of the globe. Obviously it was just before the Syrian civil war broke out, which then took into my area Jordan, Lebanon, refugees and all that kind of stuff. And it suited me totally. So by getting that right on day one, I was happy with my responsibilities. Had I not been successful on day one, it would have been a far less fulfilling period as minister.

CH: And did you feel from the outset then that you had the responsibility to go off and do it? Did you have that freedom?

AD: Yes. The advantage was not just that I was dealing with bits of the world I liked and knew about, but also I was given far more discretion and control over the areas because Africa, Pakistan, and Afghanistan were handled by the Secretary of State and were very, very time consuming and it left me leeway to get on with what I wanted to get on with.

JG: And just thinking back to those early few weeks in DfID, what surprised you the most?

AD: It struck me that it was clear that ministers beforehand had not really challenged officials on first principles. They were administering, if you like, the status quo and not challenging the existence of things from first principles. So Andrew Mitchell [then International Development Secretary] was very good at reviewing where we were operating, how we were operating, whether we were accountable, whether there was there value for money, things like that. So that was a very fundamental root-and-branch exercise which earned respect, introduced efficiencies, and galvanised DfID I think just in time for some enormous challenges that hit them in the face, like Syria and Libya and things like that.

JG: You mentioned negotiating your own particular area in DfID but did you have a sense of your initial priorities when you entered office?

AD: I think the important thing is, you know, a wise minister needs to know what he doesn’t know and then to try to learn about the culture and operations of the department. We had a lot of discretion on the budget and that kind of stuff, so the impact and effectiveness of what we were doing had to be understood. So travel was very important and the travel schedule was quite gruelling, but then it is only if you are getting your feet dusty in a country that you can see if you are doing any good at all.

There is quite a lot of variety in the DfID job. On the one hand you are dealing with primitive toilets in Bangladesh, the next thing you are at a meeting of a development bank in New York or dealing with a United Nations refugees thing so it is varied and it is, to all intents and purposes, like being a deputy foreign secretary. It has very, very important diplomatic dimensions.

travel was very important and the travel schedule was quite gruelling, but then it is only if you are getting your feet dusty in a country that you can see if you are doing any good at all

JG: Was there anyone you saw as a good role model, coming into the post?

AD: Well, I don’t think you can see how a minister behaves if you are in opposition and so it is an impossible concept. The concept is irrelevant and immaterial because there is no way you could. I mean, I think if you had been a special adviser and you had been in a department before and you had watched how a minister behaved, then that could be a role model thing. But if you hadn’t done that, no, no.

JG: So based on your experience, how would you describe the main roles and duties of a minister?

AD: You are stewards of the nation’s money and the integrity and efficacy of its use. You are there to explain and defend what you are doing to Parliament, which is the accountability bit. And a very important bit which, you know, some get and some don’t is you have a very important leadership role in galvanising a department, bringing out the best in them, and flushing out the worst.

And some of these personnel things, you come up against obstacles, because they never, ever like to sack anybody or move them or admit they are no good. That is the main weakness of the Civil Service. It is total weakness that they defend their own against ministerial disapproval of performance. Hopeless, it is absolutely their worst weakness. Timid HR handling. I always think that the permanent secretary ought to have something of the headmaster’s study about them and they don’t anymore and they need to. They are not chief operating officers for diversity, they should be at the top of their class, really. Otherwise, sorry, what was the question?

JG: It was about describing the main roles of a minister.

AD: I think really trying to be a figurehead who is known to enjoy and want to bring out the best in officials is very, very important, rather than just a bird of passage who makes demands – very important.

CH: Were there ways in which you tried to instil that? I mean, you have talked about the relationship with the private office and the relationship with the permanent secretary, were there ways that you tried to…?

AD: Yes. Get out of the office, walk the building, herograms, saying thank you, particularly to people in the field who, you know, sometimes feel remote from headquarters. I would cause havoc, sometimes, by saying, ‘Get me the head of DfID, I don’t know, Jerusalem on the phone’. ‘Oh why, minister?’ I said, ‘Just get them on the phone’. And of course they listen in, if they want to, they listen in. It took time to realise they are listening in to all calls because they don’t tell you, there is not a light that comes on on your phone, but that was fine. I would pick up the phone and say, ‘I have just seen your briefing on whether we give money to the, whatever it is, health centre in Jerusalem or something, very well written, think it is very good, I will decide it tomorrow, thank you very much’. That kind of thing is very, very important, I think. And you get a reputation for it. Or someone had a miscarriage, phone them up and say hope you are all right and it does, it spreads like wildfire.

CH: And you talked about private office and how important that was and the difficulty changing HR and all that. But did you find ways of setting up your office to suit your operating style?

AD: My office became known, within a year, as a good one to work in. Two reasons: one, it was the go-to office for cutting through crap and getting things done and the second thing was I wanted people in it to go up. So it was a proving ground – hard work, fun, proving. It was open and cheerful but very applied and that then enhanced it as the go-to office, you know, to come and say, ‘The Secretary of State is being really awkward, how to I handle that?’ ‘Oh dear, we will sort that’. Things like that.

JG: You mentioned the diversity of your role at DfID so this might be a tricky question to answer, but can you give us a sense of the day-to-day reality of how most of your time was actually spent?

AD: It was always very crammed. We only had three ministers and a world to cover and there always had to be one minister in the UK so diary planning was pretty difficult. So lots and lots of trips abroad to field offices. Syrian fundraising in Kuwait, all that kind of stuff, you know, World Bank meetings, da di da di da.

I tried to construct my working day so that anything that needed a decision took place in the office and not out of a red box at night. Because then you can always say, ‘Can you get Fred on the line? I don’t understand paragraph 10’. And normally I would say, ‘Can you just get Fred to pop down? I just want to work it out’. And then I could say, ‘Okay, now I understand, that is my decision’. So it needed a balance between travel, very well-crafted paper flow, and meetings – obviously visiting dignitaries, people from the UN, and that kind of stuff but also officials giving a general brief on something like the status of our Caribbean programme, which I completely reshaped.

And part of the ministerial stamp on how to do things was to, in my case, rail against long, repetitive cut-and-paste briefs full of jargon and acronyms. I said, ‘Stick it in logical prose or I will send it back’. And my office – in fact they gave it to me when I left – I had scribbled at the top of something ‘execrable rot’ and they framed it and they gave it to me at the end, in a frame, as we are not going to stand for waffle, ‘execrable rot’.

I tried to construct my working day so that anything that needed a decision took place in the office and not out of a red box at night

CH: Did you manage to change that behaviour then, after a while?

AD: Yes. Oh, another thing, the Permanent Secretary and Secretary of State were good at this, perhaps once every two months we would have what they call a ‘town hall meeting’, an all-staff meeting in the atrium. And we could give a little update, some observations. And you could lighten it up by saying I ban the word ‘catalysed’, ‘showcase’ and other things and, you know, it creates a reputation and then they know more confidently how to handle and sometimes tease the minister, which is fine.

JG: And in terms of your other roles, the constituency, parliamentary, speaking to the media, were there particular pressures on your time you found difficult to juggle or that you found ways of dealing with?

AD: Yes. What we managed to do was get a good working relationship between my parliamentary team and private office. The parliamentary team would come into the department, you know, straight up to the private office, they all knew each other. Alternatively, if there were votes here, the private office would come and sit in my office and get me to sign letters and brief me on whatever it was here. So a good working relationship between the parliamentary and the ministerial is important, otherwise you neglect your responsibilities to your constituents.

… a good working relationship between the parliamentary and the ministerial is important, otherwise you neglect your responsibilities to your constituents

JG: And I wonder if you could talk us through an occasion where an unexpected event or crisis hit the department and how you went about dealing with it?

AD: A ship crashed into Tristan da Cunha, spilt oil, and I became the saviour of the rockhopper penguin. I mean, that was one. I mean, it was very funny, ‘Minister, you are not going to believe this, you know, in the middle of the South Atlantic there is a small rock island and this blooming ship has just gone straight into it. You would think it might have missed but it didn’t’. You know, it was that kind of…

Otherwise yes, I can give you a very good example. About a week into being a minister, they came and said, ‘Minister, there is a bit of a problem’. You just go, ‘What is that?’ ‘Well, Turks and Caicos Islands are in serious deficit, here’s the picture’. And I looked at it and said, ‘What? If this keeps on going to like that, they are going to be £250 million in debt and we technically might just be liable. Why is this like this?’ ‘Well minister, it has been buried for two years. Previous ministers didn’t really want to address it’. So I essentially said this cannot go on. I insisted on appointing, essentially, our appointed chancellor of the exchequer for Turks and Caicos, replaced their finance minister. I said, ‘We are going to take direct control of the money and we are going to have an agreed plan for getting Turks and Caicos into surplus within two and a half years’.

It caused great ructions on Turks and Caicos but we did it and they are now in surplus. They paid off their debt. We consolidated all of the loans. In a related issue, the banks in Anguilla looked as though they were about to go bankrupt but we underpinned them, partly by helping Turks and Caicos. So we gave a Treasury guarantee with a firm trajectory and expiry date which will be about now and we, I sort of stopped financial meltdown in Turks and Caicos.

CH: And how did you find the machinery of the Civil Service and also other departments? Obviously Treasury and Foreign Office, as I understand it, were quite closely involved in that?

AD: Well, I ran it. Treasury weren’t really… I mean, I pieced it all together and then went to Danny Alexander [then Chief Secretary to the Treasury] and we agreed a Treasury guarantee with an expiry date, that kind of thing. Yes, the Foreign Office were involved, because there was one particular official who didn’t want to say ‘boo’ to any overseas goose so I just had to go to war with him. I agreed clear things with his minister and he was great and then he would try and adjust and circumvent and dilute and it was near insubordination dressed up as ‘yes Minister’, ‘no Minister’. It was awful. But in the end he got removed from that responsibility. We solved the problem. Otherwise, we would have had two to three hundred million dollars to pay.

… there was one particular official who didn’t want to say ‘boo’ to any overseas goose so I just had to go to war with him

JG: And it may be this issue or it may be something else, but what do you feel was your greatest achievement in office?

AD: I think injecting intellectual clarity and precision into DfID briefings; sorting out Turks and Caicos; responding, turning on a sixpence, really, to massive flight from Syria into Lebanon and Jordan. And Yemen, you know, I made this my little corner and Yemen is now in civil war. We are about to have famine. I have been saying this for three years. But holding it together and putting the UK in a main driving seat for Yemen and keeping the humanitarian and development effort going was rewarding.

I think in Yemen and Nepal, DfID, on the back of its development activity, had a massive political impact. We were really working with all the politicians for, in the case of Yemen, a transition from one President, without the disruption of an Arab Spring revolution. And in Nepal, after a civil war and Maoist dominance, we helped create a new government, which had been in deadlock for nearly a decade. They couldn’t have elections until they had a constituent assembly, they couldn’t have a constituent assembly until they had elections, and so they had this catch-22 deadlock. We helped break that.

And if you want to know, actually, what I think was my greatest achievement, such as it was, I went to Nepal two months after I became a minister and they said, ‘Well, Minister, Kathmandu is due for a big earthquake, it hasn’t had one since 1931 and any time now it could go’. And I walked around the whole city with an architect. He said, ‘Look at those buildings, if that goes, that crumbles, that crumbles, that crumbles, they go up. They build like that; it is going to be a pile of rubble’. I said, ‘In which case, we must develop the most comprehensive earthquake preparedness plan specifically for this city’. And I drove that, as my mission, for two years, from a standing start and bang, the earth shakes and very nice, they called me in three weeks ago and said, ‘I just want to talk you through what we were able to do, which we wouldn’t have been able to do if we hadn’t made plans’. They reckoned it saved perhaps 40,000 lives. And I said, ‘That will do, that makes it worthwhile’.

They reckoned it saved perhaps 40,000 lives. And I said, ‘That will do, that makes it worthwhile’

JG: And what factors were key to that success?

AD: I mean, they couldn’t do anything about the architecture and the building but the key thing was having pre-designated spaces for emergency hospital treatment in open areas outside the main built-up bits of Kathmandu; coordination with the Ghurkhas, the Indian Army, and the UN so that there was an immediate point of command and control; and pre-positioned hardware, because the danger was that Kathmandu is in a volcanic, mountainous bowl. If things were affected around the access roads over the mountains, there might be no access to the airport either, because it could be all broken up — craters and things, cracks – so the pre-positioning of sort of heavy lift equipment and that kind of stuff meant they could go straight into the rubble and begin to move things without having to ship it in or not be able to ship it in. So it was that kind of thing.

And, crucially, for the welfare of the DfID staff, we were developing an earthquake-proof compound on the existing embassy compound so that it all could be in the same place and not scattered around Kathmandu in houses, some of which were not earthquake-proof. I think it was half finished, certainly the ambassador’s house had been done, four or five other houses had been done so most people were in the compound with supplies which could last a fortnight and if you have got kids and things like that, it is what you need.

CH: And on that, I mean Turks and Caicos as well, you said that was something that came back to you after previous ministers had left it to one side and so forth. What are your reflections on the policy process in government? I mean the way in which policy problems are brought to you, the way in which you are able to bring your own policy thoughts and ideas and so forth and get them going.

AD: I mean, if something remains hidden you don’t know, because it is hidden. But I think you can best flush out these unexploded grenades if you are known to be tough but fair. If you are known to be tough but tantrum ridden, then they will go, ‘Oh god, give it to another minister or let’s hide it for another few months’. So tough but fair is fine and they don’t mind having to sort something out but they don’t like being, and nor should they, stand for being badly treated. So I think probably most things did come out.

I mean I had Turks and Caicos, and a couple of programmes I shut down. There was one in Palestinian Authority. They had supposedly a mortgage finance programme to help first time buyers in Palestine get a house. And a year into the programme I said, ‘Right, talk me through this, how many houses have been bought by Palestinians?’ And there was a stony silence and they said ‘four’. I said, ‘This is a five-star, ocean-going, copper-bottomed disaster’, and they looked stunned. Rather than bawl them out I said, ‘Right, we can’t hide this any longer, we either make it work or shut it down. I think we shut it down’. And we did, we shut it down. So a year later, when they came with something I said, ‘Well, how is this working’ and four of them, together, said, ‘It is a five-star, ocean-going, copper-bottomed…’ I said, ‘Ah’, but you know they didn’t hide it. But if they think you are an unreasonable ogre then someone else has to do it.

CH: What about the ways in which they would bring in evidence or perhaps bring in outside organisations? Obviously DfID has lots of relationships.

AD: Yes. Good question. I mean, for instance, on the financial restructuring of Turks and Caicos, the proposed generation of electricity through geothermal power in Montserrat, and one other thing I can’t remember, I insisted on bringing in an outside expert. No expensive consultants. I said I want one person who could be an informed brain to challenge the department’s internal view of this and in each case it was of enormous benefit.

And I railed against the big four, KPMG, Ernst and Young etc. I said I don’t have any of these people. Ah, except for one, here we go, forgotten about this. This is when Ernst and Young came in, a really, really good guy, as bright as a button. We decided we would build an airport on St Helena. £200 million and I said ‘never before has this department spent this money on an infrastructure project, nor has any infrastructure project been handled, you know, at such a distance. I therefore require someone who can advise me on what constitutes a proper, fair and as far as possible, risk-free building contract so we can avoid all the overruns. Someone who can oversee it, to make sure that it has been implemented as per the contract’. And as far as I know, that has gone absolutely brilliantly and I think a lot of that is down to the absolutely rigorous monitoring and drawing up a very, very tight fixed-price contract in the first place, with no variables which suddenly hit you in the gob and add £30 million.

So I think that has been a success. It has been an amazing project. Whether there will be any planes going to the airport later is another matter. But actually that was part of it, an air services contract. You know, you have got to have the building contract, the safety contract, the accompanying, if you like, hotels, accommodation for the supposed tourist benefit and an air service agreement and fuel, fuel tankage so all of these things had to come into a strict and big picture to make it all work.

JG: And what did you find most frustrating about being a minister?

AD: Occasionally the Secretary of State. It was a remarkably happy four years, actually. I think sometimes, when Number 10 thinks that it understands what is going on in a country and issues an edict without asking. Number 10 insufficiently draws on the benefit of a minister’s knowledge. That is often the case.

Number 10 insufficiently draws on the benefit of a minister’s knowledge

CH: You mentioned earlier, talking to one of the ministers in the Foreign Office. What mechanisms did you find most useful for communicating with ministers? Were committees any use or was it all bilaterals and phone conversations?

AD: The best way of achieving something is to have a good working relationship with your fellow parliamentarian, i.e. the minister, and pretty well agree with him what we want to achieve and then make sure that we make our officials jointly…

I didn’t really have any disagreements with fellow ministers. Often we had to meet in order to bang heads together between departments. So when DfID was trying to really be tough on the money in the Caribbean, the Foreign Office was reluctant to be too tough: ‘Oh, we can’t be colonial’. No, but better to be colonial and solvent than non-colonial and bankrupt. Nothing was particularly frustrating, I don’t think. No, I enjoyed it.

JG: Was there anything that struck you about the way government could be made more effective?

AD: Do you know what the biggest weakness of government is? I do not know how a Prime Minister can be Prime Minister without meeting the full ministerial team for each department from time to time in the same way a chairman or chief executive would meet his marketing department or his HR department or his finance department. So I just think the absence of that managerial structure means Number 10 becomes very insular, less well informed and dependent only on its immediate officials and those who have shoulder to shoulder proximity with the PM. And I think every two months the PM should meet the whole transport team, DfID team, whatever it is and say, ‘Right, what are you working on? What are your priorities? What are the problems? These are your marching orders’. Otherwise it is the fatuous, weekly cabinet meeting, which achieves nothing. We don’t have cabinet government anymore and really a PM not knowing actually how good his ministers are or what they are really doing.

CH: What does that come down to, though? Is it the style of the Prime Minister that causes that or is it something about the structure and the history of how the Whitehall machine works?

AD: I think Blair used to have what he called ‘stock take meetings’ every now and then, which is the sort of model I am thinking of. I don’t think David Cameron has ever done that and I just think what is a cabinet secretary for if he doesn’t suggest it and make it happen? What is he there for? You know, it is the whole machinery of government that matters.

JG: And so based on your experiences, how would you define an effective minister?

AD: I think they have got to be, well, someone who is intellectually rigorous, decisive, respected in a way that is firm but fair with officials, and someone who can have a public-facing reputation.

JG: And is there any advice you would give to a minister entering government for the first time? Anything you might have done differently had you known what you now know?

AD: What would I do differently? I mean, a lot of them are just happy to be there, the question is do they all really want to get a grip of their department? There are too many birds of passage and I think the message is do what is enduringly right, not what is just politically self-serving. I think that is the answer.

JG: And in hindsight, would have approached the role differently at all?

AD: I don’t think so. I mean, I had some really good, knotty challenges which I was able to get my teeth into. St Helena, Turks and Caicos, Montserrat, Palestine. There are areas of foreign policy which sort of smother some bits of DfID but you have got to live with that. Palestine is one of those, you know. The Prime Minister doesn’t believe in his own policy really.

I think a lot depends on the secretary of state, whether they work with their team and a lot of them do not. A lot of them are completely insular and I mean I have known Andrew Mitchell for 35 years and once every six months you would have to shut the door, go in with a sledgehammer, hit him on the head and say stop being such a prat. And the next day he would fix it. But I knew him well enough and was confident enough to say just back off otherwise you are going to look like… And if you were tough with him, he got it.

With Justine Greening, I worked less closely with her for the 18 months. She used her special advisers a lot – ah, let’s come to spads – but luckily I had my own patch and I determined never have a row with her. And it was fine. We never came to blows. But there were some very difficult moments.

Look, special advisers can be a curse or a blessing. They have a unique capacity to corrode government by souring relations between ministers and by feeding the newspapers. And so there is a fundamental issue about whether a special adviser should ever tell a minister what to do. And a lot of them think they can. You know, ‘I am my master’s voice so I tell a junior minister what to do’. And I made it very clear at the beginning to the special adviser. I said, ‘If ever, ever, ever you think you are more important than I am, I will go straight to the Cabinet Secretary’. And I said, ‘Don’t even test it’. So I laid down the law, so they kept away from me, really, which is fine. But they are a bad breed in many cases.

…there is a fundamental issue about whether a special adviser should ever tell a minister what to do

CH: What do you think causes it, is it something about the role or something about the type of people that come to it?

AD: Well, they get up themselves because they are right there next to the secretary of state, so they think that they are the bee’s knees and have got the power. And I mean I think all the [Francis] Maude reforms [for extended ministerial offices] are going to be a complete and utter catastrophe. Total catastrophe. Politicising cabinet ministers’ offices with up to 28 people or whatever it is. I mean what happens in a reshuffle? They all go and strip the place bare.

CH: But what about what you said about wanting to shape your own private office a bit more and have more power to hire and fire?

AD: It is always said that a minister can get rid of a private secretary who they don’t want just by asking.

I reckon I had probably the best private office in Whitehall. I mean a chap called Jonny Hall, he had been in the army, been in Afghanistan, he was in development, understood Whitehall, he could cut through any mush just like that, good sense of humour but he would come in and say, ‘Minister, I really think you are about to make a bog of this’. I said, ‘Well, what?’ He said, ‘Boom, boom, boom’. I said, ‘Ah, okay, I see, all right’. You know, very, very, straight talking, it was great. You know, you don’t want a yes person. But you do want someone who has got a bit of pizzazz and is not just a formula-driven, rules-driven inflexible person.

CH: I think we are out of time.

AD: Does that cover the ground? Any other questions?

JG: Just whether there is anything that we haven’t asked you about that you would like to mention.

AD: Well, I think we got there, actually, with spads. You know, on the spad thing, I mean look what happened in the Home Office. It was just a complete, just open tension, to put it mildly. And I said to the Prime Minister when whatever his name was, Nick Timothy [then a Home Office spad], did something, this was refuse to go canvassing in a by-election or something, whatever it is. And I said, ‘Look, if you have got a real row with this bloke, Prime Minister, you don’t ban him from the party list, you sack him. And if you think that he is sitting there, undermining your government, then out the door. But don’t do it by half measures in a way that makes you look politically vindictive’.

CH: On that, did you ever compare your experiences with fellow ministers and share problems and so forth in informal settings?

AD: Yes. There were some I worked with quite closely like Hugh Robertson, in the Foreign Office, Hugo Swire and latterly Mark Simmonds, he took a bit of time to settle down but he did. I had some, I mean I like him a lot, but pretty straightforward, cordial relations on security with James Brokenshire because we had some asset recovery and pursuit programmes in the Caribbean which tied in with his financial corruption stuff.

Who else did I deal with? I mean, a lot of it was Number 10, just quietly and after, on Libya and Yemen, with the NSC, so I built up a good relationship with Kim Darroch [then National Security Adviser] and it was then Hugh Powell [Deputy National Security Adviser]. That was pretty good. And quite a lot of it was international diplomacy: UNRA, Prime Minister of Palestine, President of Nepal, people like that. Development banks, where the phone call, the visits, all that kind of stuff were a very important part of the job and a very enjoyable part.

CH: Building up contacts.

AD: Yes. And making sure that the British voice and British interest is properly applied, really. I used to enjoy all that.

CH: Do you miss it?

AD: No, because I chose. The PM said I could stay there as long as I wanted. I said, ‘Well, thanks very much, but I have done four years and I want to be my own man’. Look, always be a happy politician and appreciate that generations shift. My generation held the Conservative Party together after John Major, to the end of the Blair years. It filled all the ’92 intake and the ’97 intake. Filled all the sort of shadow posts for well over a decade, but you have got to realise that a new generation comes and a young Prime Minister is going to want fresh faces, new broom, so don’t hang on and be resentful, just go with the flow. And I think it is the wisest decision I have ever made was to finish in July of last year. Wisest decision I ever made, I think.

- Topic

- Ministers

- Keywords

- Foreign affairs International development

- Political party

- Conservative

- Position

- Minister of state

- Administration

- Cameron-Clegg coalition government May government

- Department

- Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Legislature

- House of Commons

- Publisher

- Institute for Government