Trade in the UK internal market

Leaving the EU creates the possibility for more trade barriers to emerge within the UK.

Leaving the EU creates the possibility for more trade barriers to emerge within the UK. As a member of the EU, the UK has abided by policy frameworks set at the EU level. In some policy areas – such as agriculture, food standards, environmental policy and procurement – the devolved administrations will have no policy framework once the transition period ends and would be free to diverge.

In December 2020, the UK parliament passed the UK Internal Market Act 2020 with the aim of preventing the emergence of internal trade barriers now the UK has left the EU and the devolved administrations have more freedom to change their regulations. The Act was strongly opposed by the Scottish and Welsh governments, which argue that it places new constraints on their ability to successfully implement new policies.

Why is the internal market important?

Fewer trade barriers allow for more trade, which in turn allows economies to specialise[1], for supply chains to be integrated and for businesses to operate more easily in multiple jurisdictions, improving productivity and consumer choice.

This applies to trade within countries as well as between countries. In some ways, frictionless trade within a country is even more important than between countries. This is because the ‘gravity model’ of trade states that countries trade more those that are closest to them [2], and so all of the countries in the UK undertake a lot of trade with the rest. And trade barriers within countries are common: for example between US states or Canadian provinces and territories.

What trade barriers could affect the internal market?

The most visible barriers to trade are tariffs on goods when they cross borders. There is no question of tariffs being imposed between the four parts of the UK. But tariffs are not the only barriers to trade, and in fact ‘non-tariff barriers’ – such as differences in regulations and standards – can be just as if not more important [4].

Differences in regulations between different parts of the UK are most likely to cause barriers to trade. The OECD identifies three ‘costs’ of regulatory divergence in an international context which also apply to an internal market [5]. Each of these could emerge when the UK leaves the EU single market if regulations diverged.

Information costs arise because a business needs to research different requirements in different jurisdictions before deciding whether to locate or sell there. For example, if Scotland made changes to packaging requirements, an English business would need to investigate what those changes were, and how costly they were likely to be, before deciding whether to sell in that market.

Specification costs are changes that a business needs to make to comply with the regulations, including differences in production, packaging or labelling. These could take the form of additional labour costs and/or different production processes which impose additional costs.

Conformity assessment costs are costs incurred in order to prove that specification costs have indeed been met, for example additional laboratory testing to show that a food product meets standards.

Each of these is a cost incurred by businesses, but there are also follow-on costs to consumers. Additional specification costs and conformity assessment costs may feed through, at least in part, into prices. Or even worse, the combination of information, specification and conformity assessment costs may make producing or selling in a country unattractive. A business may decide it is not worth designing a separate packaging process to sell into a new market. That would deprive the country of product choice and additional competition from foreign firms, both of which benefit consumers.

In addition, regulations on workers can affect how easily they can move across borders. For example, if professional qualifications in one region are not recognised in another, it will be much harder for workers to move across borders. Fewer barriers to workers moving helps to improve the allocation of workers to firms. High-skilled workers moving between regions can also be an important way in which knowledge, and therefore productivity, is transferred from better-performing regions to weaker ones [6].

How much trade takes place across the UK’s internal borders?

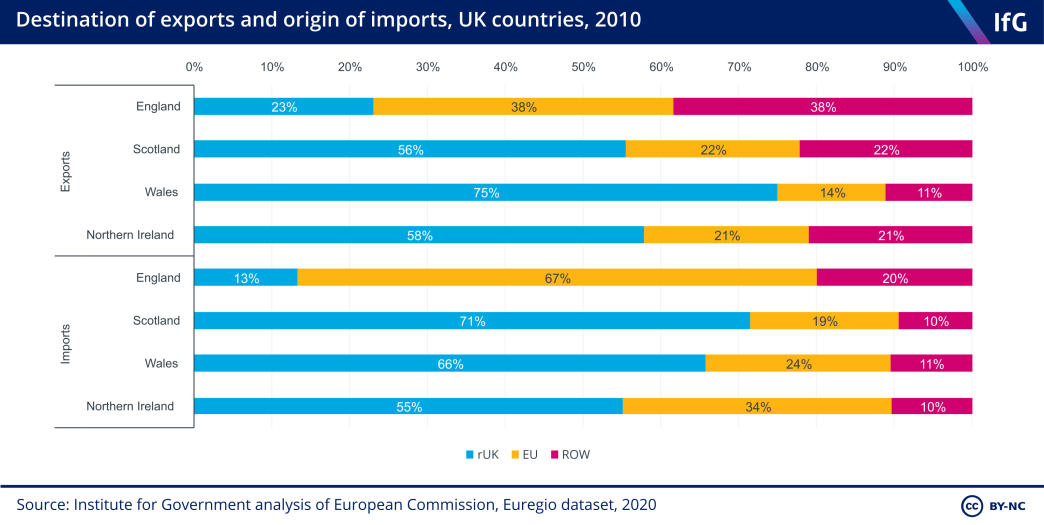

There are no official statistics on trade within the UK because no export declaration is required when goods cross between the nations of the UK. But the European Commission has published estimates of trade between different regions in the EU in 2010. While these are only estimates, they provide a fair indication of the volume of intra-UK trade [7].

Figure 1 shows that all countries of the UK trade a lot with the rest of the UK, but some countries are more reliant on intra-UK trade than others. England is the least reliant on intra-UK trade: it trades more with the EU than the rest of the UK. But Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland each trade more with the rest of the UK than all other countries in the world combined. This is even true for Northern Ireland, which also has close trading links with the Republic of Ireland.

Even these numbers understate the reliance on intra-UK trade for the smaller countries. This is because smaller countries export and import a greater fraction of what they consume and produce respectively than larger countries. England exports 13% of everything it produces. The equivalent numbers for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are 18%, 36% and 19%.

Are there cases where regulatory divergence can be beneficial?

While regulatory divergence can be costly as it increases barriers to trade, there can be benefits too.

First, regulation is an important policy tool that helps governments to meet their objectives. If the preferences of Scottish voters and English voters differ, allowing each government to set its own regulations to best meet those preferences can lead to a better outcome than a single policy that is sent centrally. This is an underlying rationale for devolving policy in the first place and also applies to regulation. If, for example, Scottish voters were more concerned about animal welfare standards than English voters, then (ignoring for a moment other considerations), this would be an argument in favour of allowing those regulations to diverge.

Second, policy variation can lead to learning and better policy overall. Devolution can therefore become a ‘policy lab' [8] and different countries adopting different regulations can help to better identify what works. For example, Scotland implementing a minimum unit alcohol price has provided valuable evidence for England, Wales and Northern Ireland about its effects and how to ensure it is implemented effectively [9].

How can regulatory divergence be managed?

Broadly, there are two ways in which regulatory divergence can be managed to limit trade barriers.

The first is harmonisation, whereby different countries agree a set of common or minimum standards. This reduces barriers by keeping regulations the same but leaves little scope for countries to choose their own regulatory framework.

The second is mutual recognition, whereby a good that can be sold in one location can also be sold in another. In principle this allows countries to adopt their own regulatory frameworks, but it may limit the impact of those regulations. If England adopted looser regulations on, say, packaging, a business could abide by those regulations and still sell their product in Scotland even if Scotland wanted to impose higher standards.

In addition, the principle of non-discrimination, which prevents regulations that would, directly or indirectly, favour producers in one part of the UK over the rest, prevents regulations from being used as a tool of protectionism (while still permitting regulatory divergence). An example of indirect discrimination would be a limit on how far a good could travel before being sold.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of the government’s approach?

The UK government and devolved administrations have, since 2017, been working on common frameworks in different areas. Depending on the area, this could include harmonisation, minimum or maximum standards or mutual recognition. The benefit of this approach is that it allows for flexibility. In some areas the devolved administrations might be willing to harmonise, while in other areas mutual recognition might be more appropriate. However, the weakness of this approach is that it relies on coming to an agreement at the ministerial level. As of June 2021 only a handful of common frameworks have been finalised.

The UK Internal Market Act puts the principles of mutual recognition and non-discrimination in law within the UK. While this ensures a uniform approach and is likely to limit new trade barriers, it risks missing out on the benefits of managed divergence. Under the Act, the mutual recognition principle has fewer opt-outs than the EU single market, so the devolved authorities have even less ability to block, for example, food produced under lower standards in England, if England chose to diverge in that way. Such broad application of mutual recognition gives the smaller UK nations little incentive to increase standards, and little ability to effectively impose those standards in practice.

The Institute for Government has made recommendations about how the UK government should work with the devolved administrations to manage the UK’s internal market – through both common frameworks and the UK Internal Market Act – going forward.

- Costinot, Arnaud, and Dave Donaldson. “Ricardo’s Theory of Comparative Advantage: Old Idea, New Evidence.” American Economic Review 102.3 (2012): 453–458. © 2012 AEA

- National Bureau of Economic Research, The Gravity Equation in International Trade: An Explanation, August 2013, www.nber.org/papers/w19285

- Kathuria S and Shahid S, Why do smaller countries benefit from greater trade with their neighbors?, World Bank Blogs, February 2015, https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/why-do-smaller-countries-benefit-greater-trade-their-neighbors#:~:text=Exporters%20in%20the%20smaller%20countries,and%20the%20less%20efficient%20losing.

- World Trade Report 2012, D. The trade effects of non-tariff measures and services measures, www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/anrep_e/wtr12-2d_e.pdf

- OECD, International Regulatory Co-operation and Trade, www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264275942-en.pdf?expires=1599575815&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=27880AE776C362ADD44A8D0F740449F4

- Trippl M and Maier G, Knowledge Spillover Agents and Regional Development, November 2010, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-14965-8_5

- Joint Research Centre, Regional Trade Data for Europe, https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/432cf8a7-fd5e-4816-a70c-633a7380c77c/resource/aa669f01-9e4e-4ebd-a814-3e4b697965ff

- Paun A, Rutter J, Nicholl A, Devolution as a policy laboratory: Evidence sharing and learning between the UK’s four governments, Institute for Government February 2016, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/devolution-policy-laboratory

- Scottish government, Alcohol and drugs, www.gov.scot/policies/alcohol-and-drugs/minimum-unit-pricing/#:~:text=We%20implemented%20a%20minimum%20price,Scotland%20and%20for%20wider%20society.

- Topic

- Brexit

- Keywords

- Withdrawal Agreement Trade

- Country (international)

- European Union

- Publisher

- Institute for Government