Public inquiries

What is a public inquiry and what is its purpose?

What is a public inquiry?

Public inquiries are major investigations – convened by a government minister – that can be gifted special powers to compel testimony and the release of other forms of evidence.

The only justification required for a public inquiry is the existence of “public concern” about a particular event or set of events. Inquiries have addressed topics as wide-ranging as transport accidents, fires, the mismanagement of pension funds, self-inflicted deaths in custody, outbreaks of disease, and decision-making that has led to war.

What is the purpose of a public inquiry?

The purpose of public inquiries has been much debated over the years. Discussions peaked around the passage of the Inquiries Act 2005; this legislation has determined the form and style of almost every inquiry since.

According to the former Department of Constitutional Affairs – and the Ministry of Justice which replaced it – the Government considers “preventing recurrence” to be the primary purpose of public inquiries.

Jason Beer QC, the UK’s leading authority on public inquiries, argues that the main function of inquiries is to address three key questions:

- What happened?

- Why did it happen and who is to blame?

- What can be done to prevent this happening again?

All inquiries start by looking at what happened. They do this by collecting evidence, analysing documents and examining witness testimonies.

Inquiries then often draw on experts and policy professionals to help them form recommendations. These are intended to guide the Government and others to make the changes which will prevent recurrence. Between 1990 and 2017 46 inquiries made 2,791 recommendations.

How common are public inquiries?

Inquiries are a feature of modern UK politics. At the end of 2017 there were nine open inquiries. The last time there were no active public inquiries was 27 years ago and since 1997 there have never been fewer than three running at any one time. The number of open inquiries peaked in late 2010, when there were 16 running concurrently.

There were 69 public inquiries launched between 1990 and 2017, compared with a mere 19 in the previous 30 years. The growth in the use of public inquiries has taken place alongside a longer-term shift away from other forms of investigation, such as royal commissions.

What do public inquiries cover?

Each public inquiry begins when its terms of reference are set out. These are specific instructions outlining the questions that the inquiry should address, the types of information and feedback that the Government wants, and often a sense of when the inquiry should issue its report.

Increasingly, inquiry chairs consult on the terms of reference with individuals and groups affected by the issue. Partly because of this, terms of reference have been growing longer and more detailed.

There are exceptions. The terms of reference for the 2013 Hutton Inquiry, for example, merely stated that the inquiry was to “urgently conduct an investigation into the circumstances surrounding the death of Dr Kelly.”

In contrast, the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) Inquiry – convened in 2017 to examine ministerial decisions on the funding of the RHI scheme by the Northern Ireland Executive – has 1,185 words in its terms of reference. These outline 14 specific questions to address; a further 17 points cover the inquiry’s principles, methods, cost controls, reporting and time frame.

Who leads a public inquiry?

Although initiated and funded by government, public inquiries are run independently. Ministers have the power to remove a chair or terminate the whole process – but no minister has ever exercised this power.

Each inquiry is led by a panel led by a chairperson. The choice of the chair lies with the minister who initiates the inquiry, and the tendency is to favour judges.

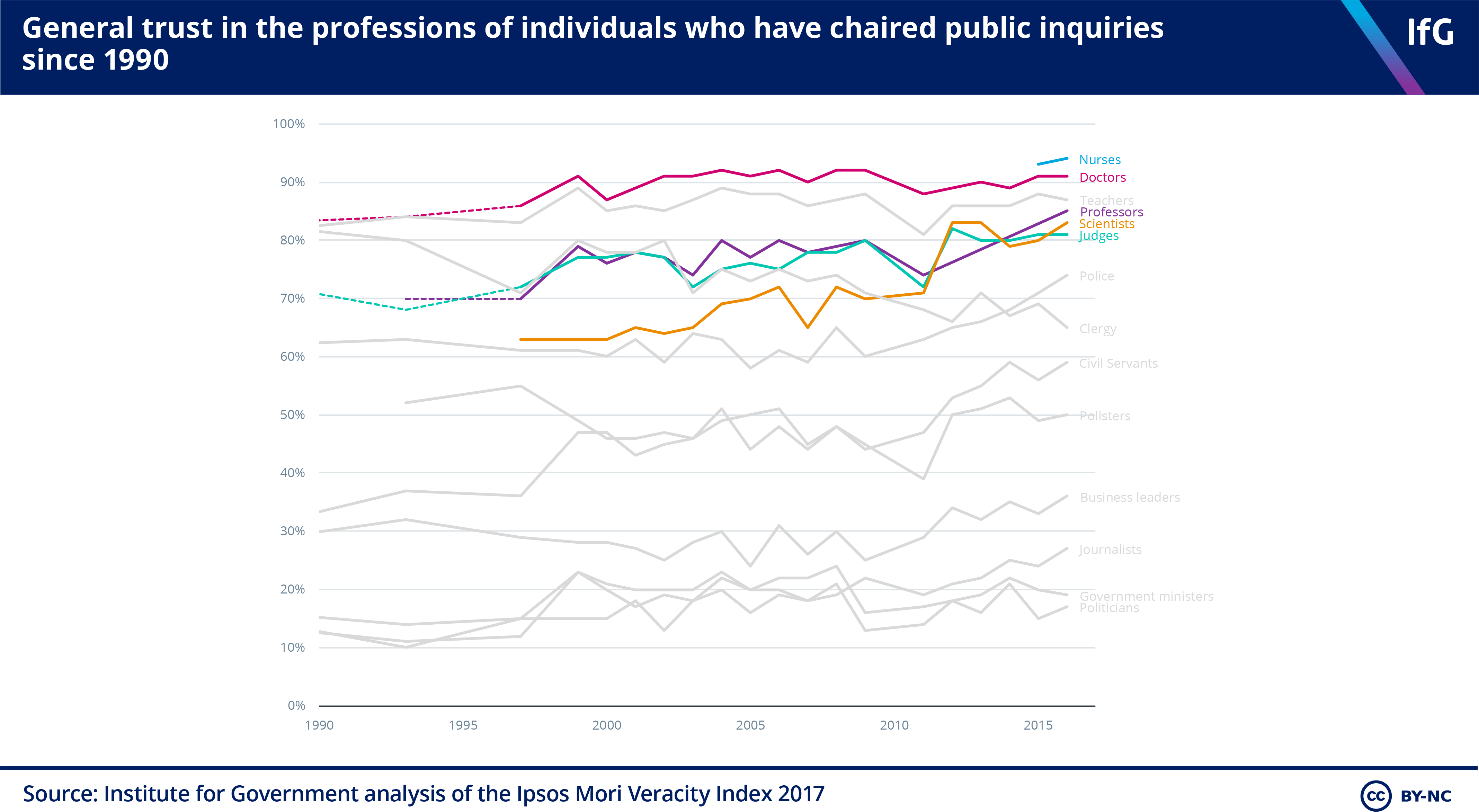

When chairs are from a non-legal background, they tend to be drawn from those professions that enjoy a high degree of trust amongst the UK public. Scientists, social workers, doctors and engineers have all successfully chaired inquiries.

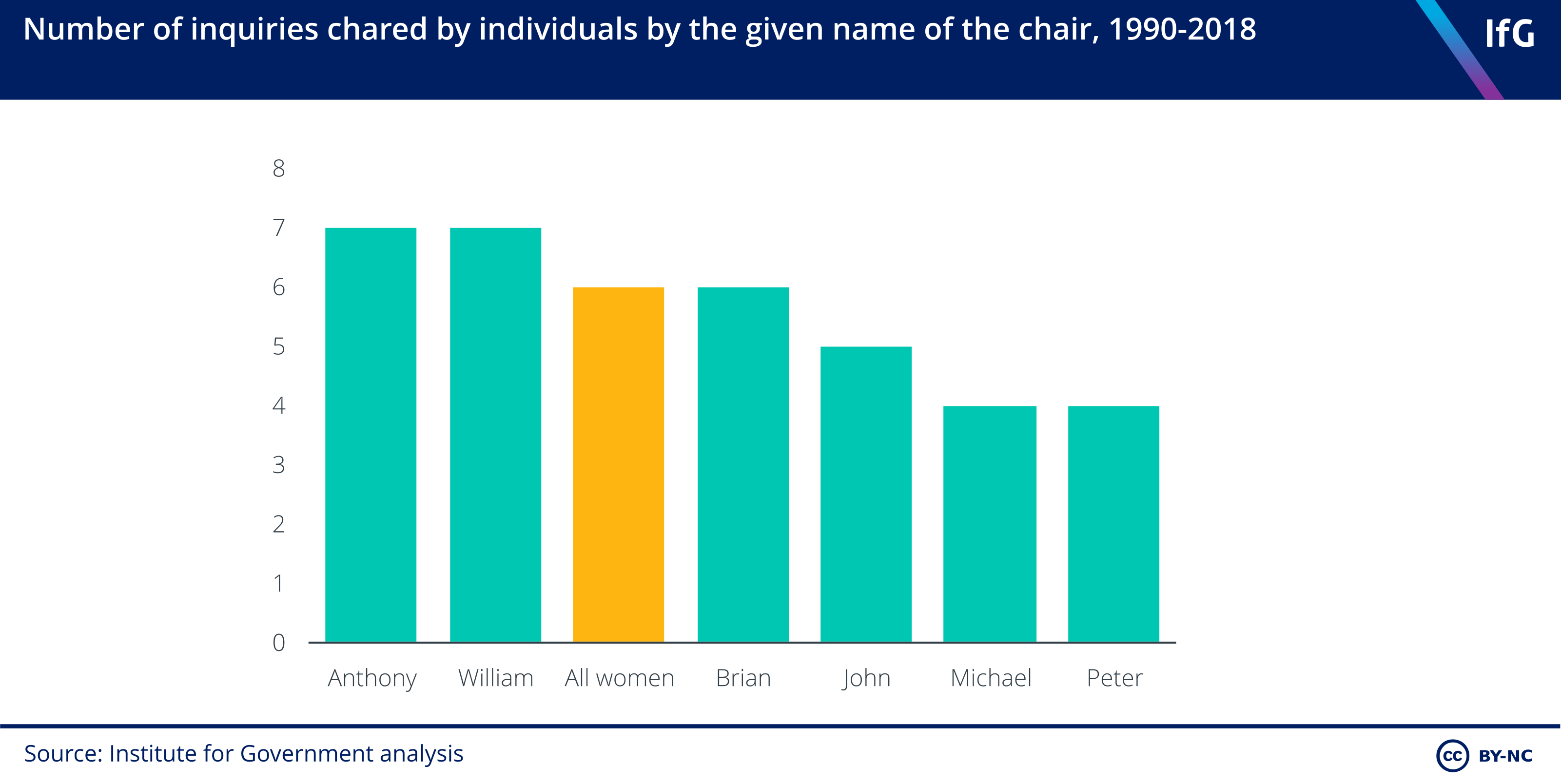

Inquiry chairs tend to lack diversity – typically being old, white and male. Between 1990 and 2017 there have only been six inquiries with a female chair, fewer than the number of inquiries chaired by someone called either Anthony or William.

What is the legal basis for public inquiries?

Most inquiries are now convened using the Inquiries Act 2005, which provides a uniform set of powers and rules for how an inquiry operates.

Before that, at least ten different pieces of legislation had been used to provide a statutory basis for inquiries.

Inquiries can also be convened on a non-statutory basis. Non-statutory inquiries lack the subpoena powers and ability to take evidence under oath that are afforded to statutory inquiries. They are regarded as less adversarial than their statutory counterparts and enjoy more freedom to define how they operate, particularly with regard to taking evidence in private.

How long do public inquiries take?

Public inquiries have a reputation for being slow-moving beasts. In contrast to inquests, which are supposed to take less than a year and must make a formal report offering an explanation to the Chief Coroner if they take longer, inquiries have no set time frame.

The 69 inquiries launched between 1990 and 2017 have varied a lot in duration, although most take around two years to report back. The shortest inquiry was the Hammond inquiry into ministerial conduct relating to the Hinduja affair; this took only 45 days. The longest was the inquiry into Hyponatraemia-related deaths; this took 13 years and three months to complete.

Why do some public inquiries take so long?

Public inquiries are commonly delayed when criminal investigations by the police take place at the same time. Inquiries cannot determine criminal or civil guilt – a function reserved for the courts. However, criminal investigations and trials running alongside inquiries will often involve many of the same witnesses. Some may be unable to give testimony to an inquiry because in doing so they risk incriminating themselves. Such legal complexities are common and invariably slow inquiries down.

Inquires must review thousands of documents and take witness testimony. Even under ideal circumstances they take time due to the sheer volume of evidence they need to consider.

Some inquiries have also been delayed due to staff turnover. Few have struggled as much as the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, which by the end of 2017 was on its fourth different chair. Other inquiries have lost chairs to sickness and death, delaying their progress.

How much do public inquiries cost?

Inquiries are notoriously expensive. The Bloody Sunday Inquiry cost £210.6m (in 2017 prices).

Between 1990 and 2017 the UK and devolved nations spent at least £630m on public inquiries (2017 prices). The actual cost will have been higher, since not all inquiries publish their costs and others are ongoing.

A major factor in the cost of inquiries is their length: retaining legal counsel, office space and a secretariat for an extended period of time is expensive.

The Institute for Government has examined how public inquiries can lead to change.

- Topic

- Policy making