Joining and leaving the House of Lords

Most Lords members are life peers – nominated for their lifetime, but without their peerage passing to their children.

Who is eligible to sit in the House of Lords?

Members of the House of Lords are often referred to as ‘peers’ – a peerage being a title granted to a person by the King (for example, duke, earl or baron). But not everyone with a peerage is eligible to sit in the Lords. Since reforms in 1999, only a small number of people who hold hereditary peerages sit in the Lords.

Most Lords members are life peers – nominated for their lifetime, but without their peerage passing to their children. Life peers must be a British, Irish or Commonwealth citizen with UK residency, pay taxes in the UK and be at least 21 years old. They must be nominated by the King on the advice of the government. Women were not able to sit as life peers until 1958; and have only been able to sit as hereditary peers since 1963.

What are the different routes into the House of Lords?

There are three main ways to become a member of the House of Lords:

- by appointment (either political or non-political)

- by hereditary entitlement

- by virtue of holding a specific role

Appointments

Most members of the Lords are appointed as life peers. Life peerages were created by the Life Peerages Act 1958. Life peers are appointed for the duration of their lifetime, though they can choose to retire.

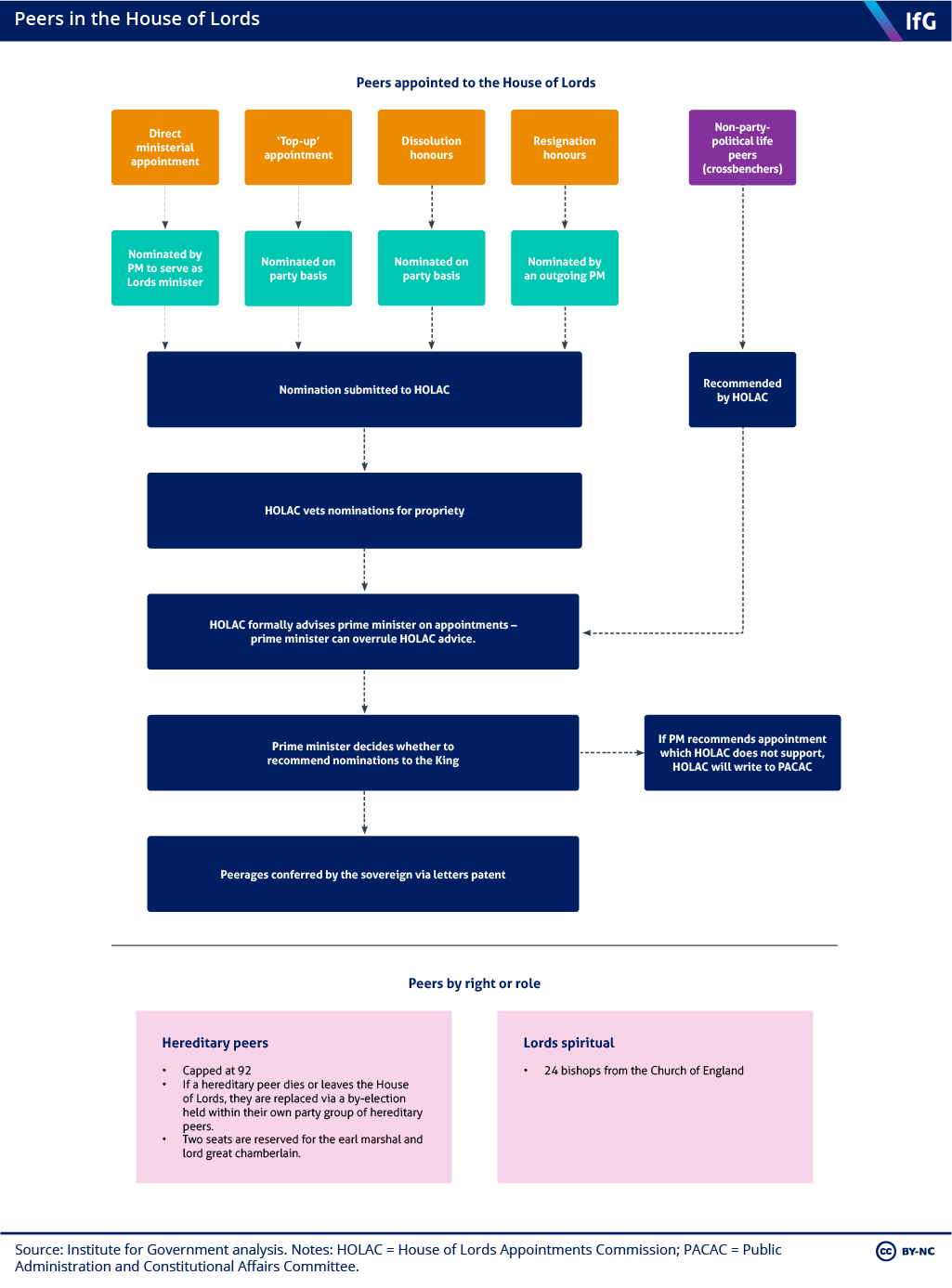

Some appointments are political, meaning they are made by a particular political party (though nominations must go via the government, before being formally approved by the King). These can be made via:

- Direct ministerial appointments – when the government appoints somebody to the Lords so that they can serve as a minister (for example, when David Cameron was appointed to the Lords to allow him to take up the role of foreign secretary).

- ‘Top-up’ appointments – when a party wishes to increase the size of their membership in the Lords.

- Dissolution honours – at the end of a parliament, prior to a general election, parties may nominate MPs leaving the House of Commons to the Lords.

- Resignation honours – appointments made by a prime minister when they step down from office, usually to reward aides and other colleagues.

Appointments through all these routes are overseen by the House of Lords Appointments Commission (HOLAC), an independent body established in 2000 to advise the prime minister on the propriety of appointments.

Other appointments are non-political. HOLAC leads on the nomination of these. Life peers appointed this way sit as ‘crossbenchers’, indicating that they are not affiliated with any political party. Non-political appointments are designed to ensure a greater diversity of backgrounds, skills, and experiences in the Lords.

Hereditary entitlement

Hereditary peers have their titles passed down within a family, and until 1999 had a long history in the Lords. The House of Lords Reform Act 1999 took away the right to membership of all but a few peers with hereditary titles. A maximum of 92 hereditary peers are now allowed to be members of the Lords (unless a hereditary peer is also given a life peerage, in which case they do not count towards the 92).

If a hereditary peer dies or leaves the Lords, a by-election is held to choose their replacement. This means that hereditary peers are the only members of the Lords to go through any form of election to sit in the Upper House.

These by-elections must be held within three months of a vacancy and use the alternative vote system. Ninety of the 92 hereditary peers are elected by members of their own party or group in the Lords. The details of which hereditary peers get to vote, and for whom, are set out in the Lords’ rules, which were based on the party makeup of hereditary peers before the 1999 reforms. These state that:

- 42 are elected by Conservative hereditary peers

- 28 by crossbench hereditary peers

- 3 by Liberal Democrat hereditary peers

- 15 can be elected by the whole House of Lords (that is, including life peers)

- the remaining two spaces are reserved for people who hold specific offices (the earl marshal and lord great chamberlain).

Anyone who holds a hereditary peerage – as recorded in the official Register of Peerages – but does not currently sit in the House is entitled to stand in these by-elections, as part of the same party or grouping as the person they are replacing.

Entitlement by holding specific roles

Some people automatically become members of the House of Lords because they hold specific roles – most notably the archbishops of York and Canterbury, and a further 24 bishops in the Church of England known as the ‘lords spiritual’ (as distinct from the secular ‘lords temporal’). Lords spiritual are only members while they hold their clergy roles, though are often offered life peerages after retirement.

Separately, the 12 most senior judges in the UK – known as the law lords, or ‘lords of appeal in ordinary’– used to be members of the House, back when it still had a judicial function. But the opening of the UK Supreme Court in 2009 meant that the Lords’ role as the highest court in the UK was ended. The 12 law lords who sat in the House at that time retained their membership, though they are not allowed to speak or vote in debates until they have retired from the Supreme Court. It has become conventional for representatives of other major religions, such as the chief rabbi, to be appointed to the Lords. But it is only the Church of England—as the established church—that that has seats in the Lords formally guaranteed to it: other religious figures are appointed as life peers.

It is convention that former Speakers of the House of Commons are appointed as peers once they have left their roles – but this is not automatic. For example, John Bercow was not appointed to the Lords after he stepped down as Commons Speaker in 2019, following allegations that he bullied staff.

How are appointees to the House of Lords vetted?

Since 2000, all appointments to the House of Lords have been overseen by HOLAC, an independent commission comprised of a chair and six members – three unaffiliated to any party and three representing the main political parties.

HOLAC is tasked with vetting all nominations for life peerages to ensure propriety. It then makes recommendations to the prime minister about nominees. However, HOLAC is not a statutory body, and its role is purely advisory – meaning it is ultimately up to the prime minister to decide whether to put someone forward for a seat in the Lords to the King.

Recent events have raised questions about this process, and role of HOLAC. For example, in 2020 Boris Johnson appointed Peter Cruddas, a former Conservative Party co-chairman, to the Lords – despite HOLAC advising against it. More recently, it was reported that HOLAC originally advised Johnson against the appointment of Evgeny Lebedev, the Russian-born owner of the Evening Standard, on security grounds, before later overturning its advice. On 29 March 2022, the Commons passed a humble address tabled by Labour that will require the government to publish documents relating to Lebedev’s nomination. The government published documents in response to this humble address in May 2022.

In the last two sessions of parliament, several private member’s bills have been introduced by some peers to make changes to HOLAC and the vetting process – for example, to put it on a statutory footing. And in March 2022, the Lords debated a resolution that would have made changes such as requiring HOLAC’s recommendation on appointments to be placed in the libraries of both Houses. But any changes to the process of vetting appointments would require government support, and there is no indication that the current government plans to reform the system.

Can peers choose to give up their membership of the House of Lords?

Yes. Peerages are held until a person’s death, but the House of Lords Reform Act 2014 allows peers to resign as sitting members. To do this, they must give written notice to the clerk of the parliaments – the most senior impartial official in the Lords. Resignations cannot be rescinded. Giving up membership of the House of Lords is separate from giving up a peerage, however. Life peerages cannot be relinquished.

Can hereditary peers renounce their titles?

Yes – though again, renouncing a hereditary peerage is separate from retiring or resigning as a sitting member of the Lords.

Under the Peerage Act 1963, any hereditary peer (sitting or not) can disclaim their title. To do this, they must give an ‘instrument of disclaimer’ to the lords chancellor within 12 months of succeeding to a peerage (or, if they are under 21 when they succeed, within 12 months of turning 21).

Can peers be expelled or suspended from the House of Lords?

Yes. Reform acts passed in 2014 and 2015 mean that there are now specific conditions in which sitting peers may be expelled or temporarily suspended from the House. These include:

Conviction and imprisonment (with a custodial sentence for at least one year) – in which case a peer is expelled from the Lords

Breaking the House of Lords Code of Conduct, in which case the Lords Conduct Committee can recommend an expulsion or temporary suspension from the House, which the whole House must then vote on

Non-attendance, defined as a peer not attending the Lords for a whole parliamentary session, if that session lasts for at least six months (and unless they have sought and been granted a leave of absence)

Some peers have been suspended on these grounds: for example, Lord Maginnis was suspended from the Lords for 18 months in December 2020 for breaking the Code of Conduct by bullying staff. Eight peers have had their membership of the Lords ended due to non-attendance.

Can a peer have their title removed?

Yes, but this is procedurally difficult as it requires primary legislation – and so is rare.

This last happened during the First World War, when the Titles Deprivation Act 1917 gave the government power to remove peerages from peers who “during the present war [have] borne arms against His Majesty or His Allies, or who have adhered to His Majesty’s enemies”. The Act has never been repealed, but its references to the ‘present war’ means it could not realistically be used and so a new act of parliament would be needed.

- Keywords

- Parliamentary scrutiny Accountability

- Legislature

- House of Lords

- Publisher

- Institute for Government