The cost of coronavirus

There are many costs associated with the coronavirus pandemic, not least the lives lost as a result.

There are many costs associated with the coronavirus pandemic, not least the lives lost as a result. This explainer focuses on one aspect of the cost: how much the public sector will borrow this year as a result of the pandemic and the economic policy response. This explainer updates the main findings of a paper – The Cost of Covid-19 – published in September 2020.

The coronavirus pandemic, and associated public health response, has had profound economic consequences. A smaller economy and policy measures designed to support public services, businesses and households have led the government to spend much more and raise much less in tax revenues than originally planned. The path of the economy and the public finances this year remain uncertain and will depend on the path of the virus and progress in the rollout of the vaccines. The numbers in this explainer reflect the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR’s) central scenario for the economy and the public finances, published in November 2020.

How much will coronavirus cost the public finances in 2020/21?

Figure 1 Change in forecast for 2020/21 public sector net borrowing between March 2020 and November 2020

Figure 1 shows how the OBR’s forecast for public sector net borrowing in 2020/21 – that is, the difference between total public spending and total receipts from tax and other sources – changed between March and November 2020. This is what we describe as the cost of coronavirus.

The deficit is now expected to be £394bn in 2020/21, which is £339bn higher than had been anticipated before public health restrictions were first imposed back in March. As the figure shows, this increase can be broken down into several factors.

First, there are those automatic changes to the deficit as a result of changes to the economy – these are sometimes referred to as automatic stabilisers. These include lower tax revenue and higher welfare spending as a result of economic activity being reduced. A combination of other forecast changes have had the opposite effect, reducing forecast borrowing. The most important of these is lower debt interest spending due to lower interest rates. Together these other forecast changes have reduced forecast borrowing. Taken together, these changes have increased the deficit by £83bn.

Second – and far more important in its impact on borrowing – have been the policy measures that the government has taken. Since March, the government has announced a raft of extra spending on public services, tax cuts, grants and concessionary loans to businesses, and help for households through wage subsidies, higher welfare benefits and more. These measures have helped to cushion the negative effect of coronavirus on the economy. However, their immediate impact on the public finances is to increase expected borrowing this year by £244bn.

The remainder of this explainer looks at the reasons for the increase in public borrowing in more detail.

What has happened to economic growth this year?

The pandemic and public health restrictions have severely restricted economic activity. In the second quarter of 2020 (April to June), GDP (that is economic activity) was 22% below the level in the final three months of 2019 because the pandemic and government-imposed lockdown prevented much economic activity.

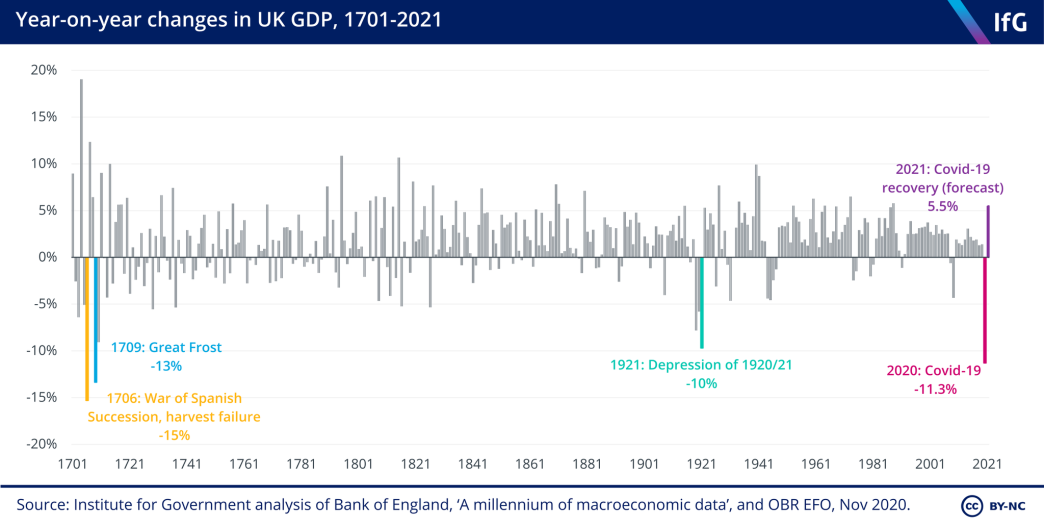

Economic activity has increased since then, but in 2020 as a whole the OBR expects economic output to be 11% lower than it was in 2019. That would be the biggest annual contraction in over 300 years, since the Great Frost of 1709.

Figure 2 Year-on-year changes in UK GDP

When the economy contracts, it affects the public finances. Taxes are levied on economic activity, such as work and consumer spending. If economic activity falls, so do tax receipts.

Government spending also normally increases when the economy contracts because more people rely on the welfare system, which supports those on low incomes. However, this automatic effect only explains a very small part of the overall spending increase that has occurred since March. Most of the increase has come about because the fall in GDP prompted the government to choose to spend more money supporting businesses and households to try to protect them from the worst of the pandemic. The big transfers from the government to the private sector (discussed below) mean that the private sector has, on average, been largely shielded from the negative effects of lower economic activity. Instead, the government has borne the brunt of the impact through the very big increase in government borrowing.

How has the government spent money in response to coronavirus?

The government has taken a raft of actions in response to coronavirus, most of which have involved additional spending. These can be divided into three areas: support for businesses, support for households and support for public services.

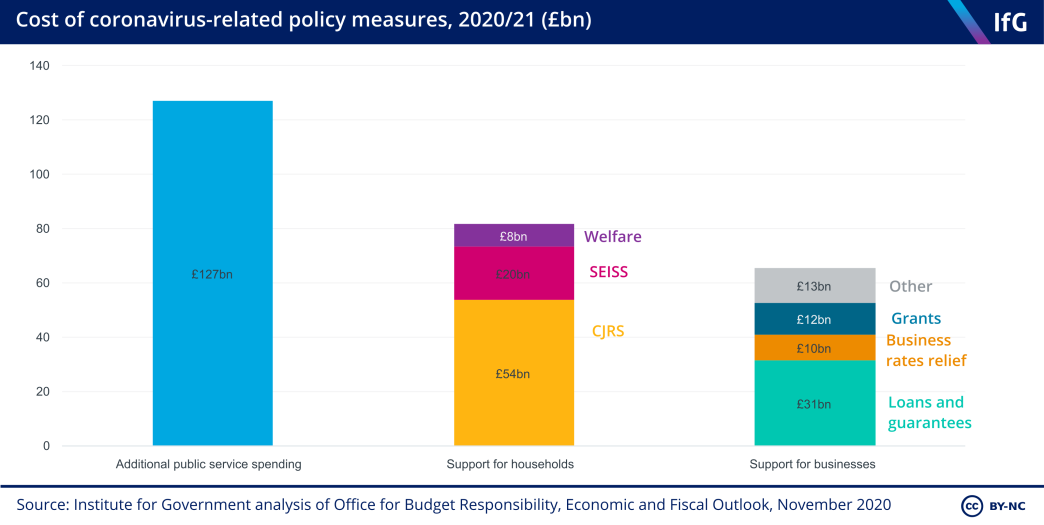

Figure 3 Cost of coronavirus-related policy measures, 2020/21

Additional support to help businesses weather coronavirus is expected to cost £66bn. Of this, £44bn has been additional spending (the remainder is through tax changes, discussed below). This spending includes grants to businesses in badly affected sectors (such as hospitality and leisure). The biggest single cost is the anticipated future write-off of loans which the government has guaranteed. In total, £87bn is expected to be loaned to businesses under three separate schemes. Of that, the government is expected to have to foot the bill for £31bn that is expected never to be repaid.

Support for households has been provided through three policies, costing a total of £82bn. First, existing benefits have been made more generous, most importantly through a £20-per-week increase in Universal Credit payments for eligible families. The second, and largest programme, is the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS, or furlough scheme). At its height, it supported over nine million jobs, paying 80% of wages while those people were unable to work. Thirdly, the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) has paid up to 80% of self-employed people’s previous profits (based on their 2018/19 financial year tax returns) provided they meet certain conditions. All three policies are expected to remain in place until April 2021.

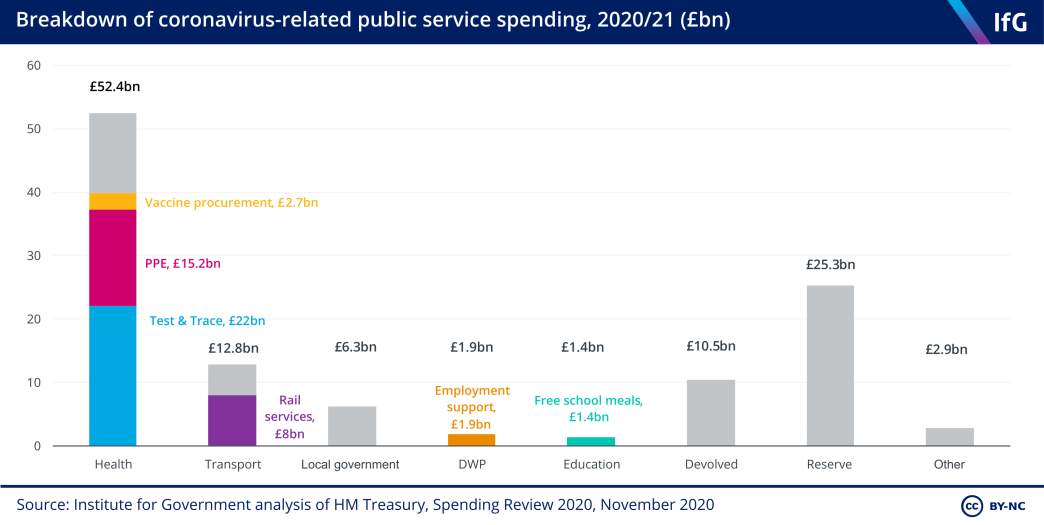

Figure 4 Breakdown of coronavirus-related public service spending, 2020/21

The government has also spent an extra £127bn on virus-related public services. Figure 4 shows how that spending has been split between different services. Most of the money has gone on health services, including spending on the test and trace system and procuring additional Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for medical staff.

Spending by the Westminster government on services in England automatically leads to more money for the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to spend. The Treasury has also guaranteed a minimum level of spending for the devolved administrations to provide more certainty.

A substantial fraction of the money set aside for public services is currently held in reserve: almost a fifth of the allocated funds (or £25.3bn) is currently held in reserve in the expectation that many public services will need more before the end of this financial year.

Why have tax revenues fallen?

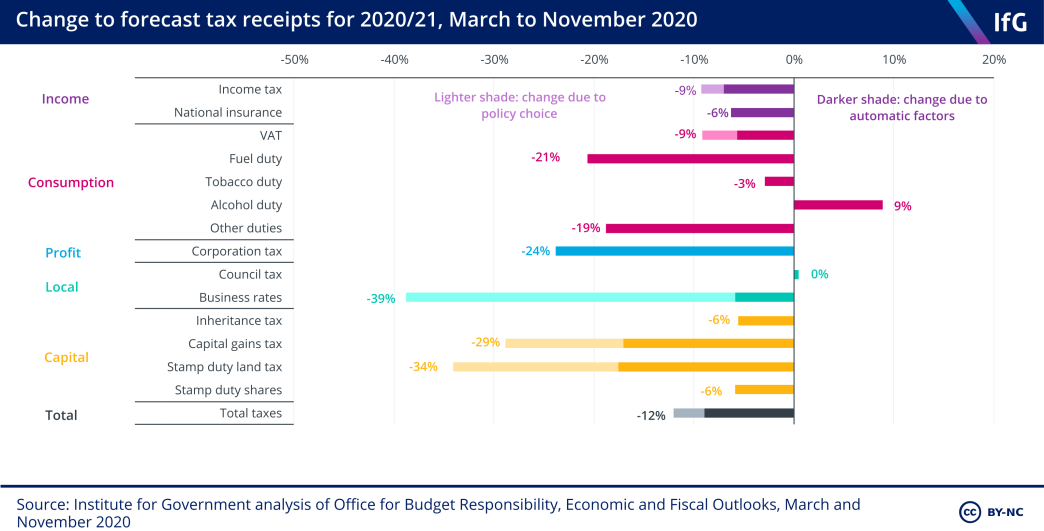

Figure 5 Change to forecast tax receipts for 2020/21, March to November 2020

Tax revenues are forecast to be much lower this year than previously forecast. Figure 5 shows how the forecasts for different sources of tax revenue have changed since March 2020. Total tax receipts are now expected to be 12% lower this year than had been expected in March, mostly as a result of weaker economic activity.

Only alcohol duties are expected to bring in more revenue this year than was predicted back in March, while council tax is expected to bring in about the same amount as was expected in March. Council tax is based on occupied residential property and so revenues of that tax have not been affected by the pandemic. The higher than anticipated revenues from alcohol duties are explained by changes in behaviour during the pandemic, with people drinking more (or more highly taxed) alcohol.

All other taxes are forecast to raise less than expected pre-pandemic. Corporation tax, capital taxes, fuel duty and business rates are expected to be the hardest hit. Corporation tax and capital taxes usually decline by more than average during a recession because profits and capital income are more responsive than other tax bases to the economic cycle. Fuel duty receipts have declined sharply as households and businesses cut down on travel in response to public health restrictions. Revenue from business rates is expected to be far lower than originally predicted, mainly as a result of the government’s active policy choice to offer a business rates holiday to firms in badly affected sectors.

Deliberate tax cuts are expected to cost the government £24bn this year, including the £10bn business rates holiday, a cut to stamp duty land tax (£2bn), cuts to VAT on hospitality and items like PPE (£6bn), and a deferral of self-assessment tax payments (£6bn) which affects both income tax and capital gains receipts this year.

What will the cost of coronavirus be beyond this year?

This explainer has laid out how borrowing in 2020/21 is forecast to be affected by the coronavirus pandemic. However, even though the costs of coronavirus this year are enormous – over £300bn – these could easily be dwarfed by much bigger costs in the future, although these are even more uncertain than the costs this year.

The costs measured in this explainer are the one-off increases in borrowing this year. But if the Covid-19 pandemic leads to long-term economic damage (for example because unemployed people lose skills or good businesses go under or cancel investment, creating permanent economic scarring), this will result in an ongoing annual cost.

The OBR central forecast anticipates that the coronavirus pandemic will do permanent damage to the UK economy so that even in 2025, when the public health impacts of the pandemic have passed, the economy will be 3% smaller than they otherwise would have expected. The cost to the public finances of the economy being permanently smaller by 3% per year is around £40bn per year (in today’s terms), mainly due to lower tax receipts. The cost to the economy and society would be even bigger: the 3% reduction in economic output equates to £70bn annual reduction in national income.

In fact, the large amounts of money that the government has devoted to dealing with coronavirus this year has in part been designed to limit the long-term costs. Spending to keep good businesses afloat and to preserve viable jobs will help the economy recover more quickly and should therefore result in a smaller permanent economic hit. Similarly, the public health restrictions the government introduced have short-term economic costs, but might reduce longer-term economic costs by allowing a more rapid recovery once a vaccine can be rolled out and preserving the health of the workforce. The government’s approach has been to accept a very high cost to the public finances in the short-term in the hope of reducing long-term pain which could easily exceed the higher borrowing this year.

- Topic

- Coronavirus Public finances

- Keywords

- Economy

- Publisher

- Institute for Government