What is covered in services trade?

If you work in the UK, the chances are you work in services – they made up 83% of workforce jobs in September 2018. Services industries cover everything from transport services, legal services, financial services to education, health and tourism. These roles often involve face-to-face interaction between buyer and seller.

Many services are not traded with other countries – for example, services such as hairdressing or cleaning. But those services industries that are traded make up 44.7% of total UK exports – amounting to £283.9 billion in 2018. Those 'exports' include services such as education and tourism where people come to the UK to spend money.

Services are an important source of innovation and growth in the UK economy. For example, a House of Lords report noted that digital services covering “software and services, internet, information and telecommunications services” created jobs at “almost three times the rate of the rest of the economy in the first half of this decade.”

How important is services trade with the EU?

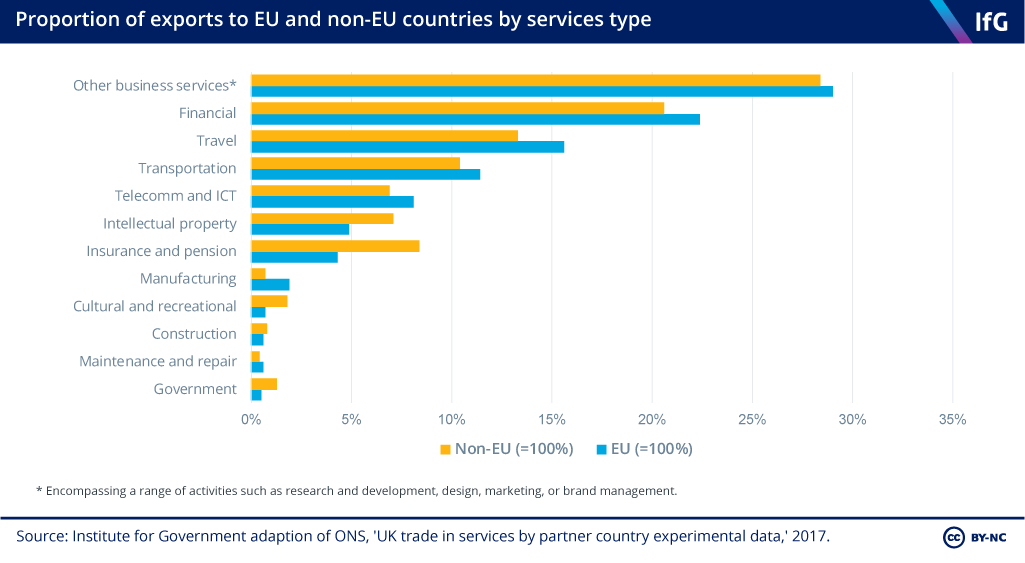

The EU accounted for 42% (worth £119.4bn) of the UK’s services exports in 2018 – the highest of any trading partner. As the chart below shows, the key sectors for EU trade are also the biggest exporters to the rest of the world.

The biggest single country the UK exports to is the US, which accounts for 22% of UK exports.

How can trade in services be supplied?

The World Trade Organization General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) is a multilateral accord that sets the basic rules for international trade in services. It describes four ways, or modes, that services can be supplied:

Mode 1 - Cross-border supply: A service is supplied into the territory of another country.

Example: A London-based UK stock-broking firm may, over the internet, buy or sell shares for a US resident.

Mode 2 - Consumption abroad: Services can be supplied by the consumer moving or travelling to a foreign market. This also includes industries relating to tourism.

Example: A UK student may travel to the US to study – and pay fees – at a US university.

Mode 3 - Commercial presence: A service can be supplied by a service supplier, through commercial presence in the territory of another country. In 2013, the vast majority of EU 28 exports (69%) to the rest of the world were supplied by mode 3.

Example: A UK-owned bank might establish a subsidiary in the US in order to lend.

Mode 4 - Movement of natural persons: A service is supplied by a service supplier through the presence of workers in the territory of any other country.

Example: An accountant from the UK may temporarily travel to the US to work for a client on behalf of his UK firm.

Why is trade in services difficult?

While tariffs do not apply to services, there are often high non-tariff barriers to cross-border trade.

These can be split into three main categories:

- Market Access: Limits can be placed on the number of foreign suppliers or total number of services transactions. For example, the on-demand services Netflix or Amazon may face demands that, say, 20% of their catalogue they offer should be made locally.

- Regulatory requirements: Laws that aim to protect the public from malpractice or fraud can be the most common barriers to trade in services. For companies these can include licenses to provide a service (like a banking license), nationality requirements for boards of directors or capital requirements (such as for financial institutions to lend). For a person it can mean requiring national qualifications to provide a service (like those needed to be doctors, accountants, lawyers) without recognising qualifications given to people in other countries – e.g. meaning a lawyer that qualifies in Argentina cannot practice law in the UK. Finally there are standards governing the services themselves (like data standards describing how data should be described and recorded).

- Restrictions on workers/movement of people: Any restrictions on short-term business visitors, intra-corporate transferees, or independent professionals traveling to provide a service. These can take the form of restrictive work visa requirements, for example short-term business visitors to the EU can stay up to 90 days within any six-month period.

In practice, a business providing a service might encounter multiple barriers. For example, a company setting up a commercial presence in another country will have to comply with lots of local regulatory requirements at the same time as facing restrictions on moving staff to temporarily work there. This raises the cost of entering into a new market.

How does cross-border services trade work in the EU?

The EU’s single market is uniquely open in comparison to other multi-national trade agreements. In principle, traders can supply services in another EU country without having to comply with all of that country's administrative procedures and rules (like obtaining prior authorisation to do business). For example, a bank licensed to operate in the EU’s internal market is immediately able to sell to customers across the EU.

In contrast, under a free trade agreement (FTA) there are often significant market access restrictions left in place, and governments reserve the right to impose restrictions on foreign companies even where they have made commitments to open their market. Many governments want to maintain the freedom to regulate or to protect certain services industries where they so choose.

By harmonising some laws across the different member states and by agreeing to mutually recognise professional qualifications, barriers in the single market for services have been significantly reduced in comparison to FTAs. However, the single market in services is not as complete as for goods and there are still many barriers left in place.

What might the EU be prepared to agree with the UK if it leaves the EU?

The EU’s draft mandate on the UK–EU future relationship negotiations states that a future agreement should go “beyond” existing commitments made to the rest of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It also states that taking into account the EU’s previous FTAs, the deal should have broad coverage but also provide for exceptions and limitations. Audio-visual services would be excluded.

Most FTAs do not liberalise services much beyond global commitments and the EU does not see this as an exception. The commitment to cover a lot of sectors also doesn’t suggest meaningful access – and the EU is clear that there will be limitations.

The Centre for European Reform argues that the EU could offer more on mode 3 (commercial presence), making it easier to set up and incorporate in the EU, mode 4 (temporary movement of workers) and mutual recognition of qualifications. The offer on mode 1 (cross-border provision) is where restrictions would be most significant. The mandate does make reference to the possibility of recognising regulated professions.

For particular sectors such as financial services, the mandate suggests “equivalence". This is the EU’s offer of reduced regulatory compliance in some sectors if it deems a third country to have met the same objectives as its own legislation. This offer is open to the rest of the world, but a House of Lords report on financial services states that the equivalence regime “is patchy in composition, and too politically insecure for firms to feel confident in making use of its provisions. It would not allow the highly integrated web of financial services within the EU to persist in anything like its current form.”

What might be the economic impact of leaving the single market for services?

An OECD study, comparing the restrictiveness of different countries’ services markets, illustrates the liberalisation achieved by the single market. It finds that, on average, members of the single market face a quarter of the restrictions that non-members do when trading with each other. On this basis, if the UK were to leave the single market, there would be new barriers to trade.

One study from CER suggests that, if the UK left the single market and agreed a free trade agreement with the EU, the UK’s services exports to the EU would be significantly reduced. The biggest impact would be on financial services exports (minus insurance and pensions) which would, at most, be around 60% lower if UK leaves the single market (putting about £14bn at risk).

The Northern Ireland department for the economy finds similar impacts on the Northern Irish economy.

NIESR’s study on the macroeconomic impact of Brexit finds that leaving the single market in services would lead to a 1.5% impact on GDP in ten years in comparison to remaining.

This contrasts with the government estimates that, compared to remaining in the EU, the Chequers proposal – without access to services – would only reduce GDP by 0.6% in the long run, while there would be a 1.4% hit from moving to EEA membership (which includes remaining in the single market for services). Arguably the analysis flatters the government’s preferred option by underestimating the impact on services of the new barriers to trade.

Could the UK agree services deals with non-EU countries after Brexit?

It depends in part on how close the UK–EU relationship ends up. The more aligned the UK remains to important EU legislation underpinning services trade (such as EU data protection laws) the less it can offer other trade partners in terms of aligning or changing its regulation to remove barriers. In addition, if the UK remains aligned to the EU on goods regulation or tariffs then it would have less to offer other trade partners in exchange for opening up services markets.

However, even with full autonomy, the UK will find it very difficult to make headway on services.

UK service providers are highly competitive and thus a threat to local providers; countries which the UK wants to do a deal with may conclude that it is domestically unpopular to liberalise work visas (likely to be one of the key asks for many countries).

Other challenges relate to the difficulty of liberalising services in general. Removing regulatory barriers for services often means restricting a government’s right to regulate, and most countries simply don’t want to agree to that. In addition, federal systems such as the US or Canada have difficulty with domestic liberalisation of services between states or provinces, let alone for foreign exporters.

As a result, few trade agreements anywhere in the world go much beyond the provisions of the GATS.

What other opportunities might there be for services after Brexit?

One of the UK’s main focuses is likely to be in multilateral or plurilateral negotiations now that the UK has now taken up its seat in the World Trade Organization (WTO). The UK’s first statement at the WTO following its exit from the EU highlighted the importance of the Joint Initiative on Services Domestic Regulation. The initiative is intended to streamline procedures for qualifications and licensing for traders around the world. However, the other major multilateral services negotiation, the Trade in Services Agreement (TISA) has largely stalled for the moment.

There could be other potential bilateral opportunities. For example, the UK could go further on mutual recognition of services qualifications and/or more liberal work visas with countries such as Australia and New Zealand.

The UK could also concentrate on smaller, more-focused deals – for example, the recently agreed UK–Australia “fintech bridge" – rather than mega bilateral deals. The deal sets up a “one stop shop service” to enable FinTech firms to access legal, regulatory and practical advice about setting up between the two markets. Co-operation agreements like these can be just as important for facilitating services trade as a big free trade agreement.

Outside of international agreements, focusing on efforts to improve the domestic regulatory regime may deliver benefits. For example, the Financial Conduct Authority chief, Andrew Bailey, suggests that the UK might move to a “more principles-based system of regulation” – rather than detailed, prescriptive rules – that could offer more flexibility than is currently the case.

But every sector is different and if there are opportunities for financial services, this may not translate into benefits for, for example, the audio-visual sector. In addition, businesses will still need to follow EU regulation if they want scale up and sell into EU markets. A prime example of this is the General Data Protection Regulation regulating the storing of EU citizens data, which is starting to become a global benchmark in other jurisdictions.

- Topic

- Brexit