Criminal courts - 10 Key Facts

Spending by Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) has fallen by 23% in real teams since 2010/11. An increase in the typical complexity of cases means that the demands places on the criminal courts system have not fallen as quickly. At the same times, HMCTS has begun to pursue an extensive programme of reforms to streamline the operation of the courts.

Between 2010/11 and 2015/16, criminal courts struggled somewhat to keep up with new demand. Since then they have managed to reduce waiting times and clear some of the backlog of cases, despite continued cutes to spending and the workforce. This suggests that the courts are processing criminal cases more efficiently, but it does not tell us what has happened to the quality of justice dispensed in those trial’s or people’s ability to access justice. These issues are harder to assess quantitatively, but anecdotally are of growing concern. Whether all of the recent efficiencies can be sustained will depend on these concerns.

For full citations and further details see the Criminal Courts chapter from Performance Tracker 2018. This analysis is drawn from Performance Tracker, produced by the Institute for Government in partnership with CIPFA.

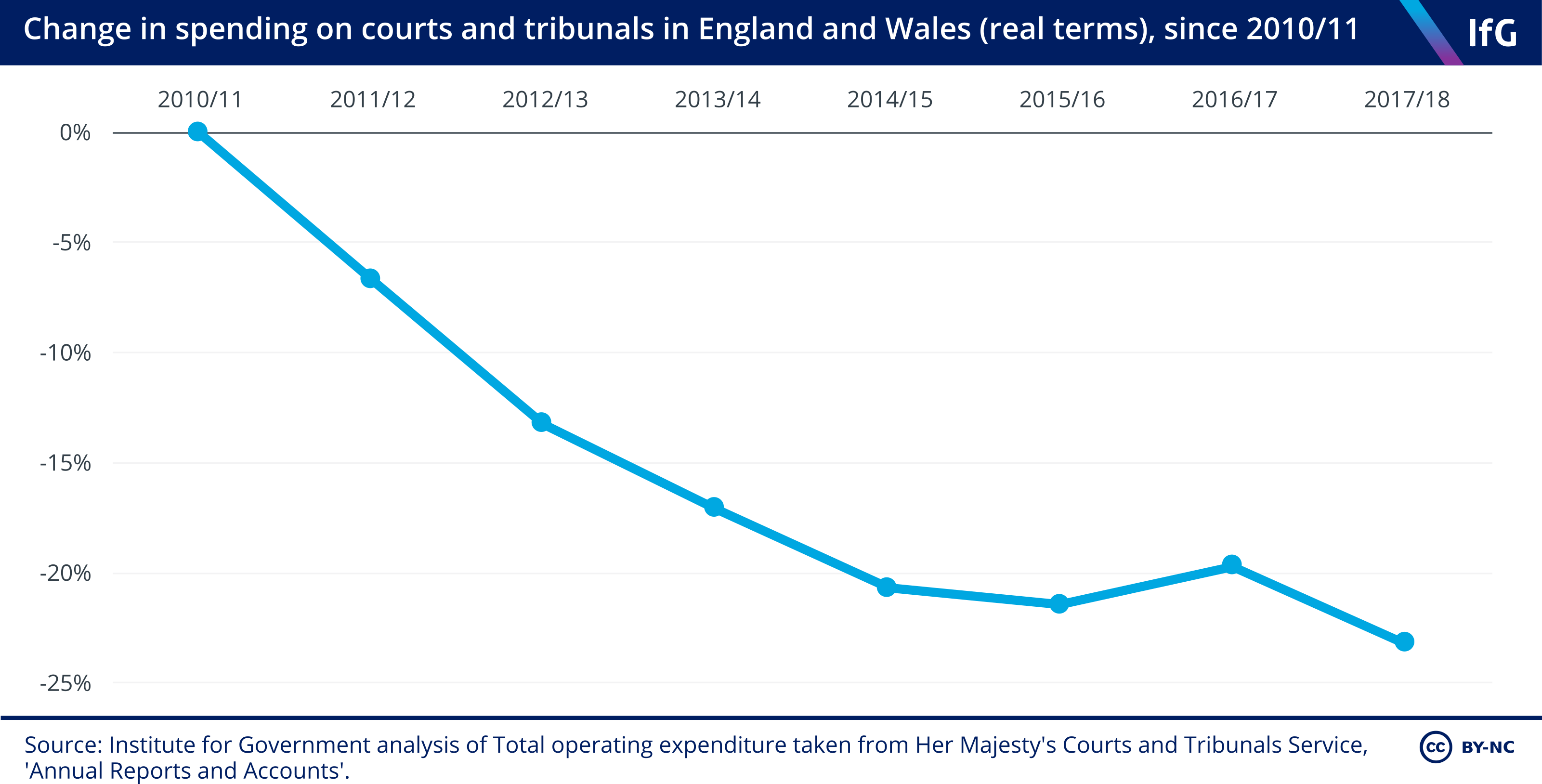

1. Spending on HM Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) has fallen by 23% since 2010/11.

- Operational spending on the whole courts and tribunals service fell by over £500m (2017/18 prices) between 2010/11 and 2017/18. We cannot say how much this reduction hit criminal courts specifically (these numbers also include civil, family, and immigration courts and tribunals) – especially as different kinds of courts share staff and buildings.

- A larger reduction in government funding was partially offset by increased fees. Government funding of HMCTS fell by 39.8% between 2010/11 and 2017/18. But income from fees charged to users of the non-criminal parts of the justice system grew by 36.8% in real terms over the same period. However, after a Supreme Court ruling in July 2017 that fees charged for employment tribunal cases were unlawful, HMCTS has had to reduce some of the fees it charges.

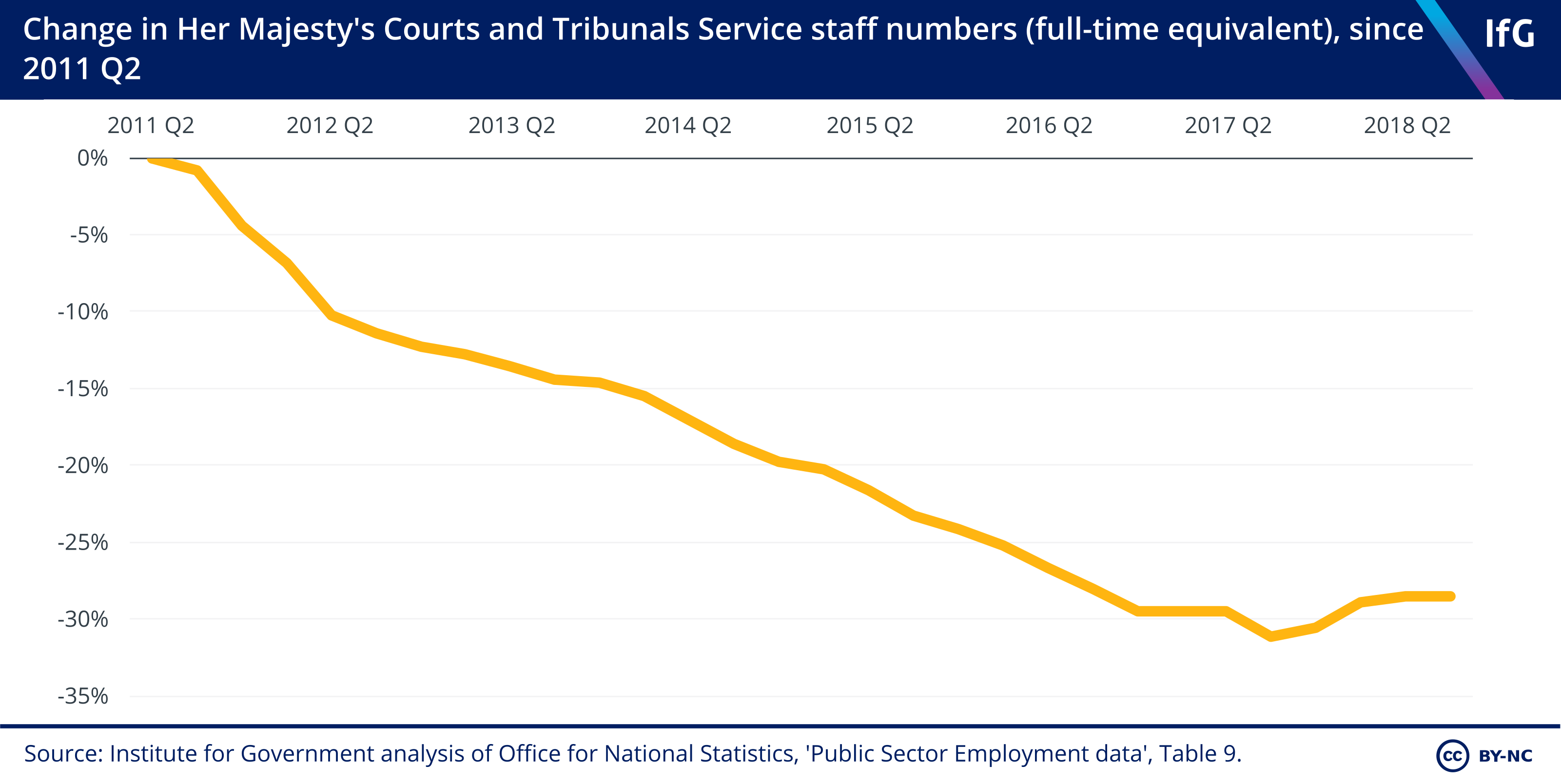

- Since HM Courts Service was merged with the Tribunals Service to create HMCTS in April 2011, staff numbers have fallen by 30%, although the HMCTS workforce is gradually starting to grow again. In March 2018 there were 14,120 FTE staff working in HMCTS. More than two thirds of these staff are employed in administrative and clerical roles.

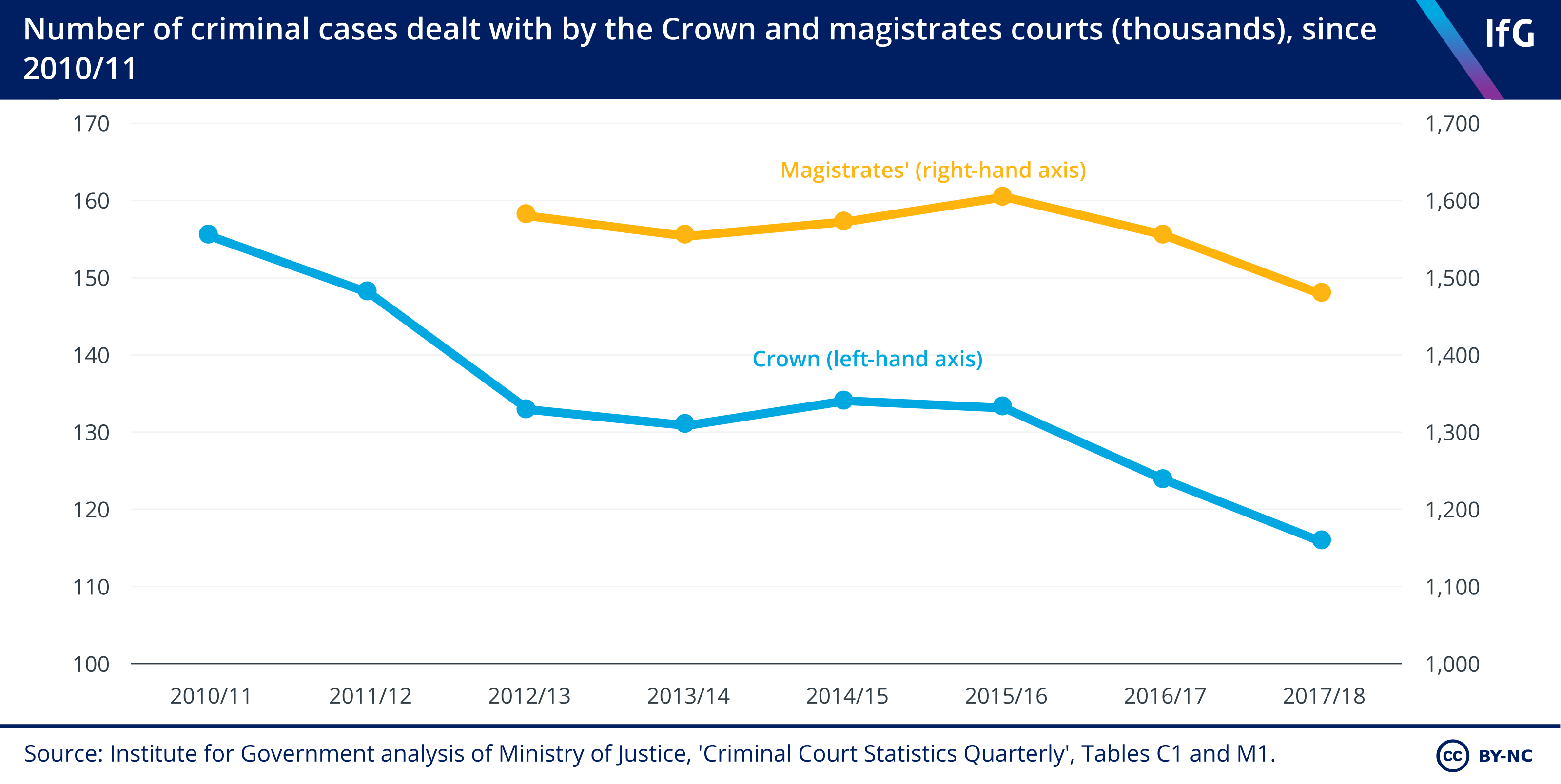

2. The number of criminal cases received by the Crown Court has fallen by nearly 30% since 2010/11.

- In 2017/18, Crown courts received 110,221 cases, down from 152,546 in 2010/11.

- This is a reversal of previous trends. Between 2004 and 2010, the number of cases received by the Crown Court increased by 25.2%.

- The number of cases in magistrates’ courts – who received the less serious cases – has also fallen. After rising marginally between 2012/13 and 2014/15, magistrates’ courts saw a 7.7% fall in cases between 2014/15 and 2017/18.

- But more complex cases – which take longer to hear and reach a conclusion – are on the rise. In 2017/18, 10.8% of Crown Court cases involved sexual offences and 14.1% involved drug offences, compared with 8.1% and 12.3% respectively in 2010/11In 2017 it took an average of 204 days from when a sexual offence was first listed in the magistrates’ court to when the court case was completed; the average for all types of crime was 28 days.

3. Criminal legal aid spending has fallen by a third in real terms since 2010/11.

- Legal aid is funded separately from the courts and tribunals system. It makes public funds available to eligible individuals to meet some or all of the costs of instructing solicitors and barristers to represent them in criminal and civil cases.

- These spending reductions were part of Chris Grayling’s planned cuts to the legal aid system when Secretary of State for Justice in 2010. Means-testing for help with legal costs in criminal cases was introduced, and fees to solicitors, barristers and expert witnesses were cut.

- There are concerns that a lack of access to legal aid has meant that individuals ability to present their case is becoming unequal. Magistrate Christopher S Morley wrote to the Magistrate magazine in January 2016, that access to legal aid “constitute[s] a real threat to the long tradition of a fair trial for all who appear before us.”

4. Staff numbers at the Crown Prosecution Service have also fallen by a third since 2010/11.

- This accompanied spending cuts. The CPS’ day-to-day spending budget was cut by 27.1% in real terms between 2010/11 and 2016/17, rising slightly by 3.3% in 2017/18.

- This may have affected the CPS’s performance. For example, in early 2017, an investigation by HMCPSI in only 60.1% of cases did the CPS comply with its legal responsibility to provide the defence with details of the prosecution’s case before the first hearing.

- However, performance is improving slightly. Based on a sample of cases examined by HMCPSI, between the autumn of 2015 and early 2017, the proportion of ineffective first hearings that were primarily as a result of CPS failings fell from 22.2% to 15.4%.

5. HMCTS spent 27.4% of its budget in 2017/18 on judges.

- This paid for the services of 847 salaried judges and 1,220 FTE fee-paid judges. The MoJ budget met the salary costs for a further 877 senior judges.

- But magistrates are unpaid. HMCTS benefited form the services of 15,003 magistrates as of 1 April 2018.

- The number of serving magistrates has fallen. Between 1 April 2010 to 1 April 2018, there was a 44.4% fall, from 26,960 to 15,003.

- Each magistrate is disposing more cases. The average number of criminal cases disposed by each magistrate each year rose from 67.6 in 2012/13 to 98.6 in 2017/18.

- There has been a smaller reduction in salaried judges. Salaried judges sit for around 215 days a year, and their number fell from 1,947 in 2010 to 1,724 in 2017 (11.5%).

- The number of fee-paid judges has fluctuated. But in 2017/18, there were 10.6% fewer FTE fee-paid judges than in 2010/11. Around four-fifths of cases in the Crown Court are heard by salaried judges who are employed full time, whereas fee-paid judges pick up around four-fifths of the workload for tribunals.

6. For the first time, the courts are struggling to recruit judges.

- A 2017 drive to recruit 25 High Court judges was left with eight vacancies. 2014/15 was the first time a recruitment drive failed to fill a High Court vacancy; in 2016 a drive to fill 14 High Court positions resulted in six vacancies remaining.

- There have also been difficulties filling Crown Court posts. A recruitment exercise for 55 new Crown Court judges in 2016/17 attracted only 44 suitable candidates – the first time there had been a shortfall. In 2017, 12.5 out of 116.5 vacancies were unfilled.

- Recruitment difficulties are set to continue. In 2016/17, the JAC carried out selected exercises for 290 judges; the number that needed to be recruited rose approximately 1,000 in 2017,18, is expected to be in excess of 1,100 in 2018/19 and is predicted to remain high in 2019/20.

- Retention is also a problem. Of those judges more than five years from their mandatory retirement age, 36% reported in 2016 that they were considering leaving the judiciary within five years, up from 31% in 2014.

7. Between May 2010 and July 2015, 146 courts were closed.

- At the end of November 2017, there were 96 Crown Courts and 160 magistrates’ courts in England and Wales.

- The number of sitting days has fluctuated. Sitting days in the Crown Court were cut from 110,969 in 2010 to 103,596 in 2013, following several years of declining case numbers. When the number of cases unexpectedly rose in 2013/14 (there were 142,670 against the forecast 129,214), the number of sitting days was increased to 105,052 in 2014 and to 113,966 in 2015. Sitting days have since been reduced and are expected to be cut further.

- HMCTS is spending less on the Court Estate. In 2017/18, HMCTS spent £253m on accommodation, maintenance and utilities, 5% less in real terms than was spent in 2010/11.

- Judges are unhappy with the physical quality of court buildings. The proportion of judges reporting it as ‘poor’ rose from 21% in 2014 to 31% in 2016.

8. The number of cases dealt with by the Crown Court fell by a quarter between 2010/11 and 2017/18.

- The number of cases dealt with has exceeded the number of new cases received in the last few years. This means that the backlog of cases has been falling; it peaked at 55,116 at the end of 2014, falling to 35,388 in March 2018.

- The average length of time taken to hear each case has increased. The average hearing time for a Crown Court trial increased by 38.5%, from 2.9 hours for cases closed in 2010/11 to 4.0 hours in 2017/18.

- The number of cases dealt with by the magistrates’ court has also fallen. This fell by 6.4% between 2012/13 and 2017/18. The average number of hearings required per case also fell, from 1.8 in 2010/11 to 1.5 in 2017/18.

- The backlog of cases in magistrates’ courts has remained fairly stable. There were 318,853 cases outstanding in June 2012 and 290,532 in March 2018.

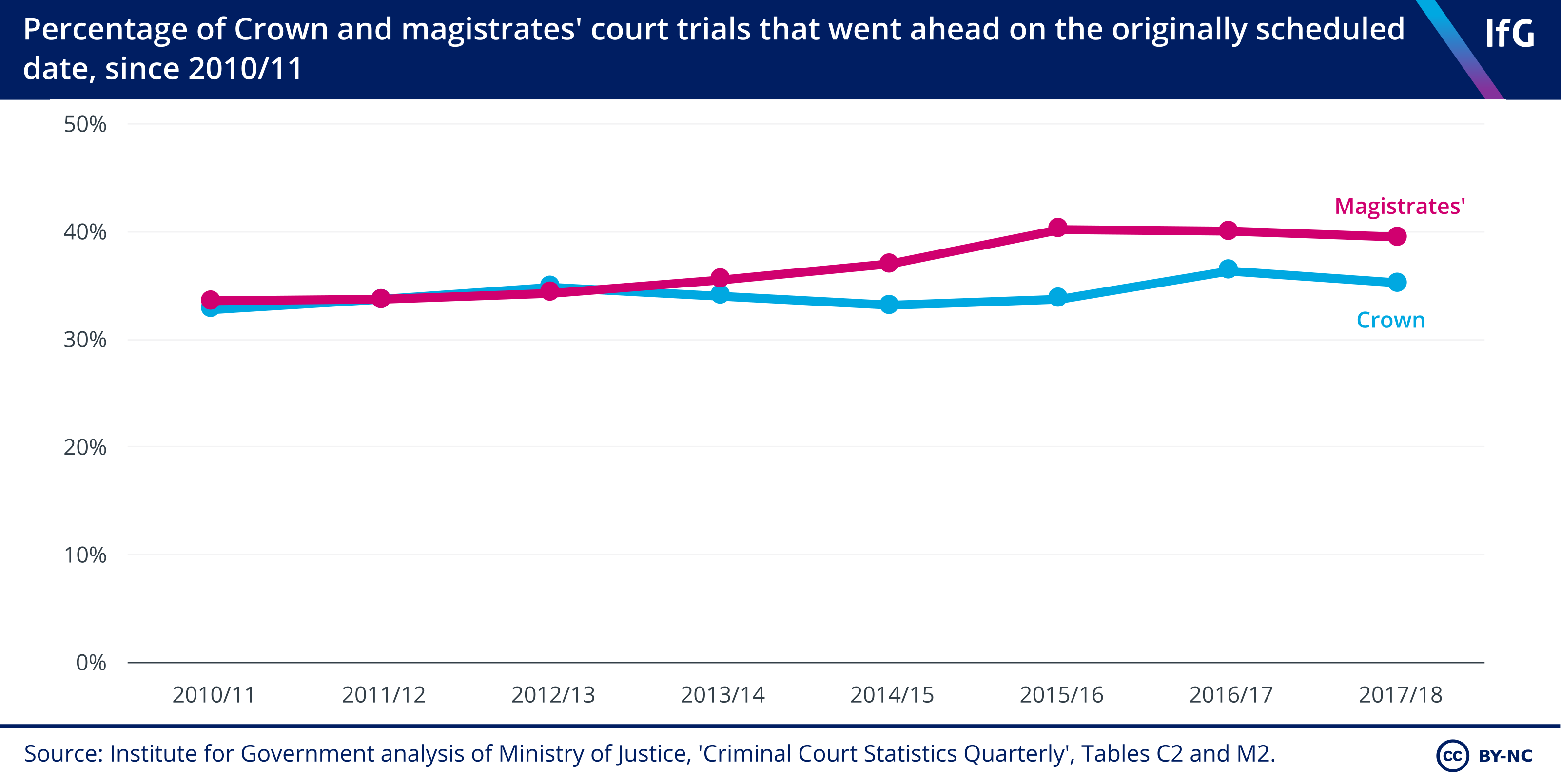

9. In 2017/18, roughly one-in-ten Crown Court cases were cancelled on the day they were supposed to take place.

- In 26% of cases, this was due to court administration problems - up from 21.1% in 2010/11.

- But more cases went ahead on the originally scheduled date. In 2017/18, 35.2% of trials listed to start in the Crown Court were ‘effective’ in this way, up from 32.8% in 2010/11. In magistrates’ courts this figure was 39.4 in 2017/18, from 33.6% in 2010/11.

- Overall, this does not suggest that the operation of the courts has been seriously impaired by the spending reductions. In process terms, the quality of the system has been maintained.

- However, concerns have been raised that the quality of justice being dispensed in those courts is slipping. One prosecutor told Penelope Gibbs, of Transform Justice, in 2016: “I have prosecuted trials against unrepresented defendants. It is a complete sham and a pale imitation of justice.”

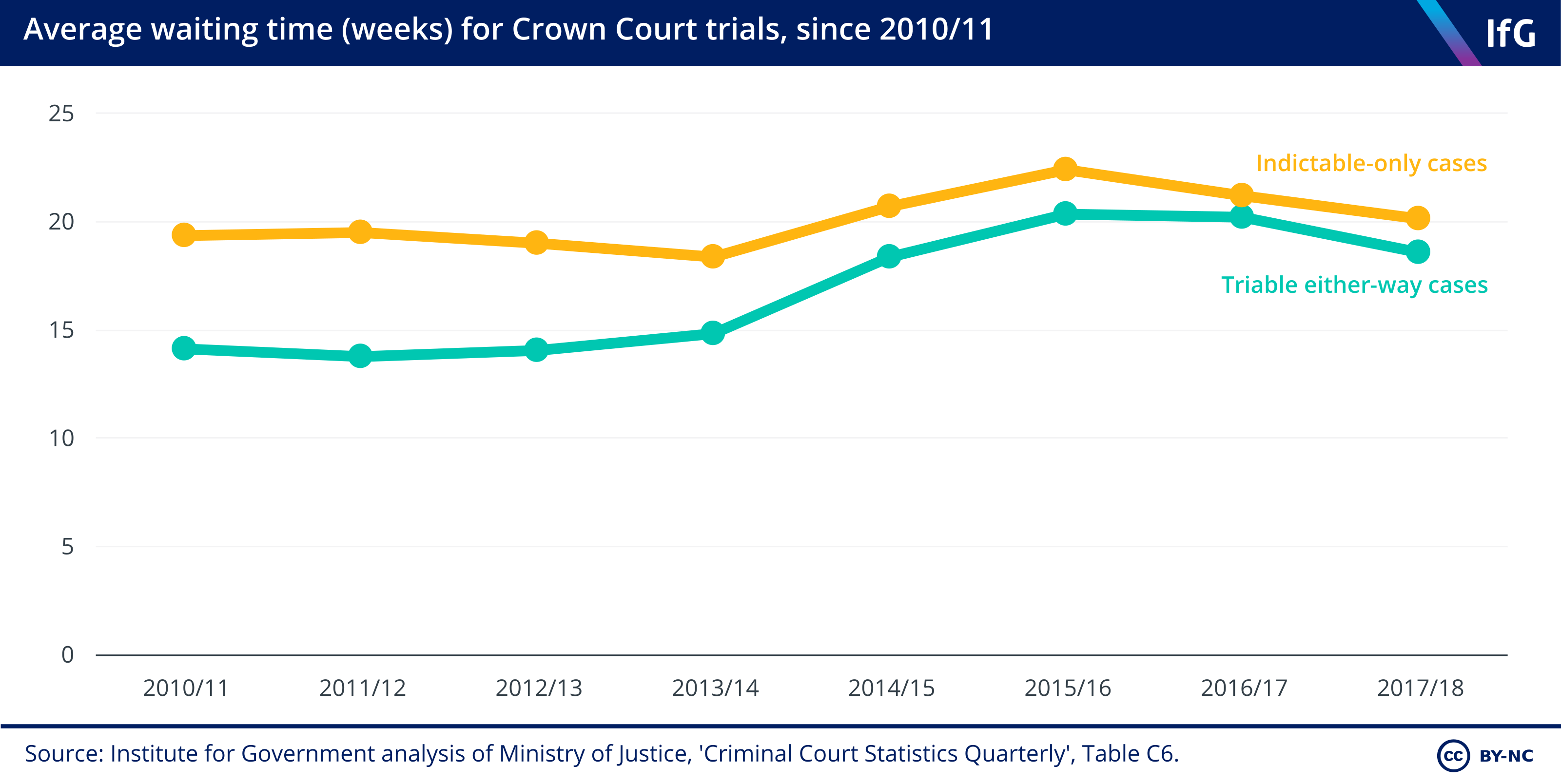

10. Waiting times between a case being sent to the Crown Court for trial and the beginning of substantive hearings fell to an average of 19.2 weeks in 2017/18.

- This is after the average waiting time increased from 16.0 weeks in 2010/11 to 21.1 weeks in 2015/16.

- The picture is similar in magistrates’ courts. The average length of time from someone being charged to their case being completed was 7.9 weeks in 2010/11 (excluding cases that eventually ended up in the Crown Court). This steadily increased and peaked at 8.8 weeks in 2015/16, but fell to 7.6 weeks in 2017/18.

- Topic

- Public services