Sir Anthony Seldon, Vice-Chancellor at the University of Buckingham, set out his top tips for every occupant of Downing Street at a recent Institute for Government event. Akash Paun explains Seldon’s assertion that by focusing on the negative, we fail to learn from when prime ministers get it right.

The old cliché that all political careers end in failure is most true of all for those at the top. And it is therefore easy to remember prime ministers primarily for the circumstances of their downfall. The blunder of Suez. The winter of discontent. The poll tax riots. The 1997 Labour landslide that buried John Major. The chaos of Iraq and the Brown coup. The shock victory for Vote Leave.

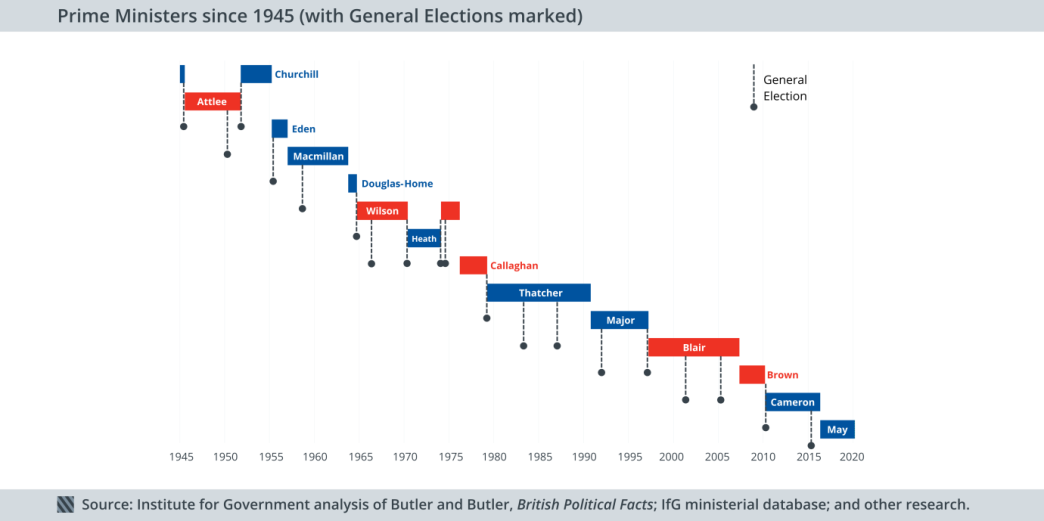

Indeed, Sir Anthony Seldon told the IfG this week, no post-war prime minister left Downing Street at a time truly of their own choosing, unless one counts the resignations due to ill-health of Harold Wilson and Winston Churchill. Scandal (Harold Macmillan), policy failure (Anthony Eden and David Cameron), betrayal (Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair) and election defeat have accounted for the rest.

But our tendency to focus on failure, rather than the less dramatic stories of accomplishment and success in office, helps to produce an overly cautious and risk-averse culture in Westminster, argued Seldon. It is better to ask instead how to be effective as Prime Minister.

Drawing on his extensive research into past premiers, Seldon set out ten pieces of advice he would offer any occupant of Number 10. These can be boiled down into three key insights: get the right people, set the right priorities and act the part.

Get the right people

On the first, Seldon argued that every prime minister must “secure the citadel”, meaning get the right staff into Downing Street and keep them there, as Thatcher did with Charles Powell and Bernard Inghams. Successful prime ministers also work closely with their senior officials as well as political advisers. It was argued that Blair’s sidelining of successive Cabinet secretaries contributed to a failure to capitalise fully upon the opportunity his landslide victories provided.

At the political level, it is crucial to have a trusted and loyal fixer in Cabinet: Willie Whitelaw to Margaret Thatcher, or Michael Heseltine to John Major. Despite holding the titular post of First Lord of the Treasury, a prime minister cannot play this role in reality, so the success of a premiership of course rests in huge part on the Prime Minister’s relationship with their Chancellor, who should be “neither poodle nor tiger”. However, Seldon saw it as unavoidable that the Prime Minister must play the role of de facto Foreign Secretary.

Set the right priorities

Second, and partly as a result of this, a prime minister must focus on their big priorities and avoid getting dragged into minutiae. A prime minister must find their own “authentic voice” otherwise the media will find it for you, by defining you in their own terms. The public must know in simple terms who the Prime Minister is and what they want to achieve in office. Since 85% of a premier’s time is not within their control, one must carve out time for reflection and relaxation, argued Seldon.

Minimising relaunches, reshuffles, announcements and reactions to events is important to enable a prime minister to focus on the grand themes of their government. However, at times of crisis, a strong prime minister must seize command and define the moment. Blair’s response to the death of Princess Diana is surely a textbook example of how to get this right.

Act the part

Third, Seldon emphasised the importance of a prime minister showing dignity and decorum that befits the office, since a modern prime minister plays much of the role of Head of State as well as head of government. This means maintaining a distance from the media, who should be in no doubt who is the master. A prime minister should also avoid rows with colleagues or staff, including in private, since every angry word or thrown mobile phone is liable to end up in the papers. But Cabinet colleagues are not your friends, and a prime minister must sack underperformers swiftly and cleanly.

Since 1945, 12 men and two women have occupied the post of Prime Minister. Seven have been Conservative and five Labour. Their tenures lasted from more than 11 years (Margaret Thatcher) to just 12 months (Alec Douglas-Home). One premier (Harold Wilson) won four elections, while three (not counting Theresa May) never tasted victory as party leader. Two (Winston Churchill and Harold Wilson) were offered a second bite at the cherry, returning to power after a spell in opposition. Only David Cameron and Churchill (until the end of the Second World War) governed in coalition with another party, while three (Wilson, James Callaghan and John Major) lacked a majority in Parliament for part of their premiership.

Theresa May has now held the position of Prime Minister for a little over six months. There is little doubt about her top priority: getting Brexit right. As the process of leaving the EU begins in earnest next month, we may start to get a clearer sense of whether Theresa May and her administration match up to her most effective predecessors.

Watch or listen to the full event – Sir Anthony Seldon: Ten things a Prime Minister should do – or not do.