Despite the devolution of fiscal powers to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the devolved governments remain dependent on the Treasury for most of their funding. But exactly how their budgets are calculated is often shrouded in mystery. Greater transparency would improve accountability, argues Aron Cheung.

As the Prime Minister contiues her tour of the devolved nations, the UK Government will be keen to emphasise the generosity of the Barnett formula, in particular towards Scotland and Northern Ireland, by which devolution is funded.

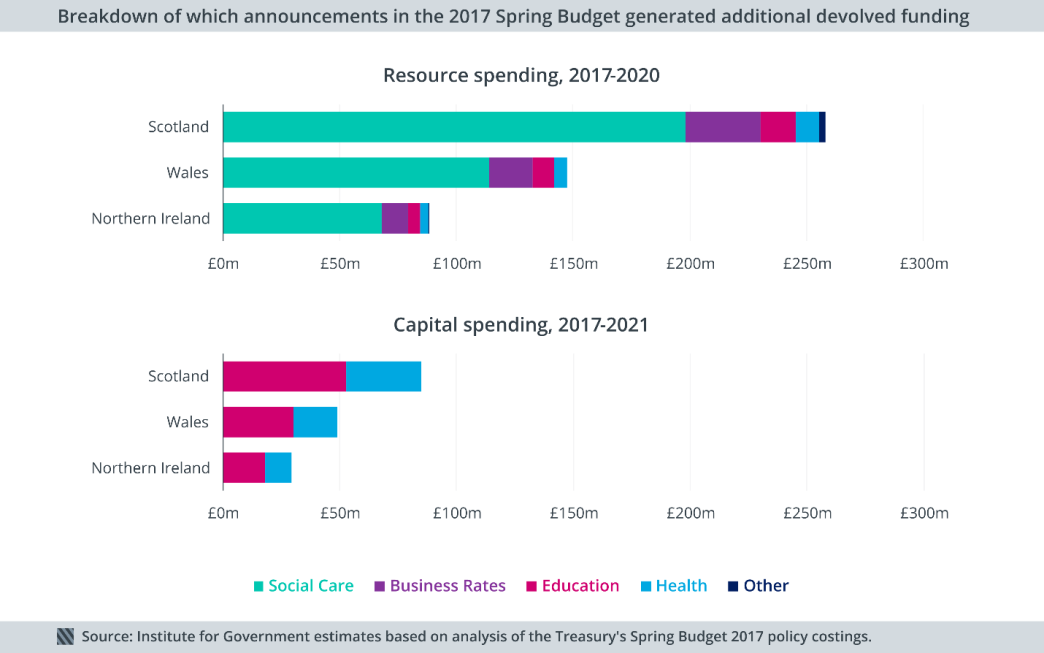

In this month’s Budget, Phillip Hammond announced £350m of additional funding for the Scottish Government, £200m for the Welsh Government and £120m for any incoming executive in Northern Ireland. Such provisions are familiar features of Budget speeches and Autumn Statements delivered by the Chancellor. When HM Treasury increases spending on public services that are devolved – as it did for schools, social care, and hospitals – the Barnett formula dictates that the administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland must also receive more money.

Simplicity without transparency

These additional spending obligations – referred to as Barnett consequentials – should be easy to calculate. For all its perceived shortcomings, the Barnett formula is at least mathematically straightforward. Devolved budgets must be adjusted by a population share of any spending changes in the rest of the UK. Put otherwise, if an additional £100m is spent on schools in England, and the Scottish population is 9.8% of the English population, then an additional £9.8m must be added to the Scottish Government’s block grant.

However, the figures announced by the Treasury will not take the form of a single payment. A press release by the Northern Ireland Office on the day of the Budget revealed that of the £120m of additional funding for the region would include £90m over three years for resource spending and £30m over four years for capital spending. Similar top-level breakdowns have been published by the Welsh Government and widely reported for Scotland, with sub-totals for resource spending over three years and capital spending over four. It is therefore somewhat strange for the Chancellor to present the Barnett consequentials as a single headline figure, when in fact there are two components paid over different lengths of time.

It is also unclear how the figures were reached. Within the many detailed documents released by the Treasury on Budget day, nowhere is it explained which spending announcements generated Barnett consequentials, and how these add up to the Treasury’s totals. To understand how the consequentials are calculated in practice, it is necessary to try to ‘reverse engineer’ the Barnett formula by making assumptions about which Budget measures relate to English-only spending. Our own attempts at doing this resulted in totals that were within about 1% of the Treasury’s totals for resource spending and 5% for capital spending, however this is based on educated guesswork and should not be necessary.

While each component of the Barnett consequentials is linked to specific policy decisions for England, it is important to note that devolved administrations will be free to spend this money on their own priorities. When the Welsh Government receives additional funding because of increased spending on social care in England, it is not required to also spend that money on social care in Wales.

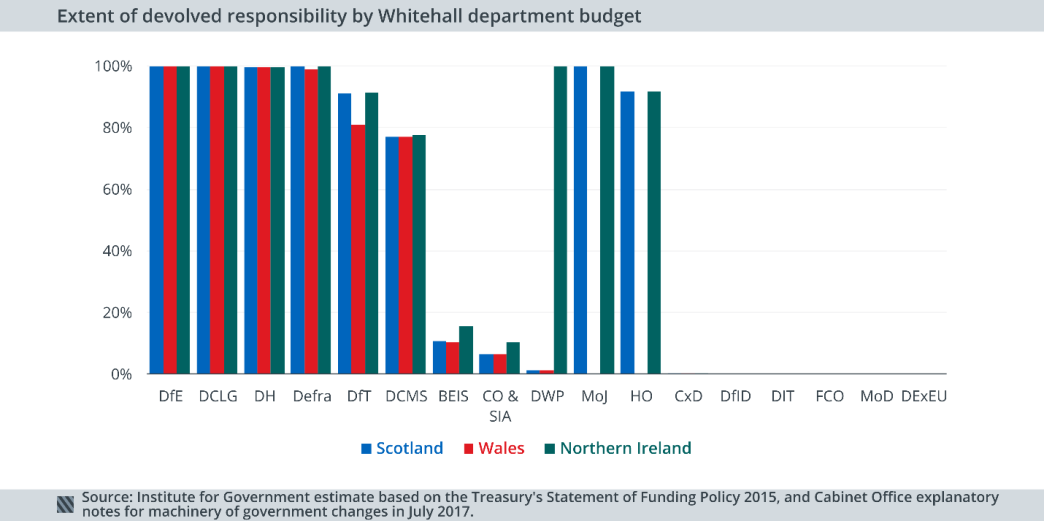

Barnett consequentials are not the only area where transparency is lacking. The Statement of Funding Policy for devolved administrations has not been updated to account for the creation of three new departments in July last year. This document outlines each department’s comparability percentage, i.e. the extent to which spending in that department can be considered UK-wide spending (which is not subject to the Barnett formula) or England-only spending (that is subject to the Barnett formula). While it is again possible to estimate these percentages, the Government should provide official figures.

If it is here to stay, fix it

The Barnett formula looks set to remain an integral part of the UK’s fiscal landscape. The Government has committed to its continued use in its Fiscal Framework Agreement with the Scottish Government, and it is unlikely that this arrangement will be revisited ahead of any second independence referendum. In Wales, the UK and Welsh governments have agreed that a customised version of the same basic formula will be used, which will ensure that the Welsh Government funding does not fall below 115% of similar spending in England.

In April, income tax will be devolved to the Scottish Parliament, and further devolution of tax powers will take place over the coming years. As this happens, block grant payments will need to be adjusted to account for the Treasury’s loss of revenue, adding an additional step to the Barnett calculations.

The details on how devolved budgets are determined are already too opaque, which undermines accountability. The IfG has previously highlighted how the Treasury can already exercise discretion in interpreting the Barnett formula. This can lead to disputes between the UK Government and devolved administrations, such as over spending for the 2012 Olympic Games. If the future entails Barnett with added complexity, enhanced transparency should be a priority.

- Topic

- Devolution