The Treasury’s attempt to repair Eat Out to Help Out's reputation is dubious

Rather than focussing on brand management, the Treasury should learn from what it got wrong about the virus, argues Tom Sasse

Rather than focussing on brand management, the Treasury should learn from what it got wrong about the virus, argues Tom Sasse

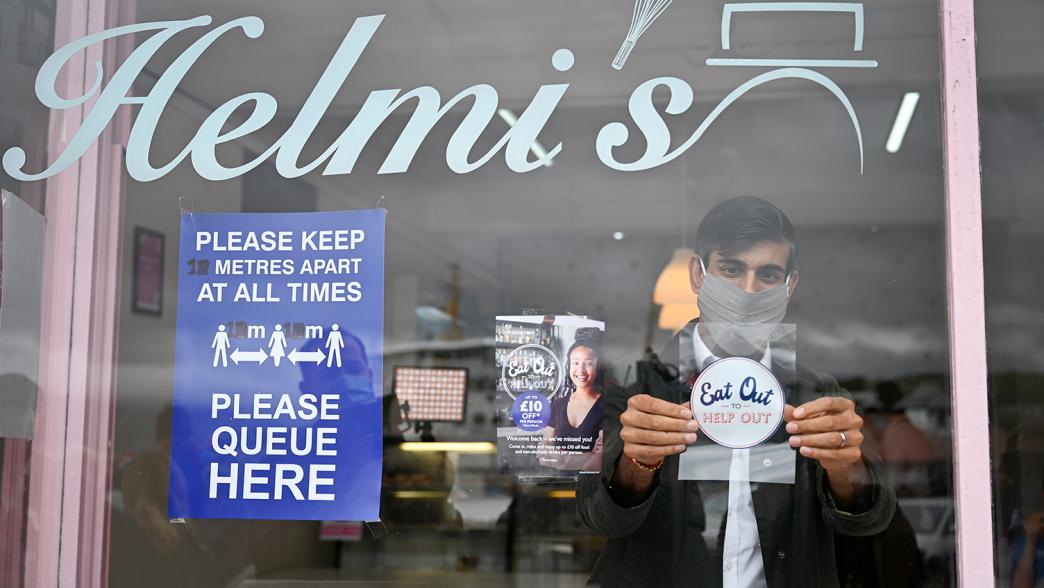

Eat Out to Help Out was the feel-good summer hit that helped launch the new chancellor to a whole new audience. The restaurant subsidy scheme (a.k.a. “Rishi’s dishes”) allowed diners to claim 50% off over 160 million meals in August, costing some £849m – much more than the £500m the Treasury predicted. But while the innovative policy, designed to boost the economy, was popular, its reputation soured amid an Autumn spike in infections, with research suggesting it helped spread coronavirus.

The Treasury press office has now fought back, briefing journalists that “new data” shows there was in fact no link to rising Covid cases. [1] But the analysis is pretty thin and does not engage properly with the criticisms – including that the scheme undermined public health messages. The attempt to limit damage to brand Rishi should not muddle thinking over the release of the current lockdown.

The Treasury has not produced robust evidence to counter criticism of Eat Out to Help Out

Several economists have analysed the link between encouraging people to gather in restaurants and rising infections. In September, Ryan Bourne of the Cato Institute cited NHS Test and Trace and Public Health England survey data to suggest the scheme boosted the resurgence. [2] In October, in a paper widely picked up journalists, Thiemo Fetzer of Warwick University analysed infection, mobility and hospitality data and found “areas with higher uptake experienced a sharp increase in the emergence of infection clusters a week after the scheme began”. [3]

Both Bourne and Fetzer acknowledged the difficulty of disentangling several effects – other restrictions were lifted, and people were encouraged to return to work around the same time – and existing differences in the risk of transmission between areas. But Fetzer used local rainfall data – a proxy for people’s willingness to go outdoors to restaurants – to establish a causal connection.

What the Treasury has briefed to journalists does not take this analysis seriously. The Sun reports that new Treasury data “shows areas with high uptake of the scheme also still had low virus levels between August and October”, and says these figures “confirm that take-up of Eat Out to Help Out does not correlate with incidence of Covid regionally”. [4]

This claim notably ignores the evidence suggesting the scheme increased transmission in specific areas, and people may reasonably wonder about its definitions of “high”, “low” and “regionally”. The Treasury has not published its analysis or data so its claims cannot be scrutinised, nor has it made any attempt to explain why the findings of other economists’ work should be discounted.

The Treasury has not shown that it was right to incentivise people to gather indoors

The criticism of the scheme goes further than the question of whether increased transmission could be associated with restaurants. We know that the virus transmits best in poorly ventilated indoor settings; most epidemiologists and economists therefore agree it was a basic and fundamental mistake to subsidise indoor gatherings. At an IfG LIVE event Professor John Edmunds, a SAGE member, called it “epidemiologically illiterate”.

Rather than using economic policies to reinforce desired behaviours, the scheme undermined efforts to explain risks. Behavioural experts say that often changing and seemingly contradictory rules mean these messages still have not landed. [5]

The Treasury was right to be concerned about saving jobs in the hospitality sector, but if that was its main aim it could have designed a scheme for takeaways, or adopted other financial support, as other countries like Germany did. Instead, it wanted to provide a big signal to a hesitant public that it was safe to venture outdoors – gather indoors, even – and return to some sort of normality.

This reflected an understandable desire to reopen the economy following four months of hugely damaging lockdown – and a judgement that in doing so the UK would avoid a second wave. But the latter view of the balance of risks and the likely impact of its policies was not shared by scientists – indeed, Edmunds revealed SAGE was not even consulted on Eat Out to Help Out – and it turned out to be badly wrong. The UK’s second wave has already been much larger than the first.

The fact that the Treasury is engaging in a PR battle now raises concerns that it has not grasped what it got wrong back in the early summer.

The government needs a more coherent approach to lifting lockdown restrictions this time around

No part of government has a complete view in responding to this crisis: SAGE cannot factor in considerations about harm to sectors of the economy and people’s livelihoods; the Treasury does not have scientific expertise about managing the spread of the virus. But it was a serious mistake that these views were not brought together better, and that government policies have drawn from very different evidence. A recent IfG report argued the Cabinet Office needs to do more to bring together expertise from across government to inform a coherent strategy.

The government cannot afford to repeat this mistake. The vaccine rollout offers a route out of the crisis but sequencing the lifting of lockdown presents a major stumbling block. Even with the most vulnerable protected, the more transmissible UK variant – not to mention the South African one – could still cause huge suffering if the government loses control again.

In a public health crisis, the public needs the government to draw a range of expertise together to enable evidence-based policy making. Unfortunately, the Treasury’s attempt to cover its tracks has the appearance of policy-based evidence-making.

- https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/13881675/rishi-sunak-eat-out-to-help-out-scheme-covid/

- https://www.conservativehome.com/thecolumnists/2020/09/ryan-bourne-its-time-to-admit-eat-out-to-help-out-was-a-mistake.html

- https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/centres/cage/manage/publications/wp.517.2020.pdf

- https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/13881675/rishi-sunak-eat-out-to-help-out-scheme-covid/

- See Susan Michie comments at IfG LIVE event

- Supporting document

- science-advice-crisis.pdf (PDF, 888.19 KB)

- Topic

- Coronavirus

- Position

- Chancellor of the exchequer

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government