Taking happiness seriously

It must actually influence policy, not just speeches.

The Prime Minister’s announcement that the Office for National Statistics is to start measuring wellbeing will only be of academic interest unless it affects the way policy is made.

No speech about the importance of wellbeing can be made without citing Robert Kennedy’s famous denunciation of the folly of purely concentrating on economic growth [video]. David Cameron’s announcement yesterday was no exception. The government has announced that it is going to try to rebalance the equation, by asking the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to measure subjective wellbeing alongside GDP – and asking people about what matters to them.

Why measure wellbeing?

Advocates point out that over the last 40 years, the economy has grown but we haven’t got any happier as a nation. Studies show there is a strong relationship between GDP and wellbeing for poor and middle income countries, but this breaks down for richer countries, where wellbeing flatlines (the so-called Easterlin paradox). Equally, the UK does consistently less well on international studies of wellbeing. UNICEF published a report almost four years ago (PDF, 1.5MB), saying our children were the most miserable in the OECD.

Measuring wellbeing by government is not new

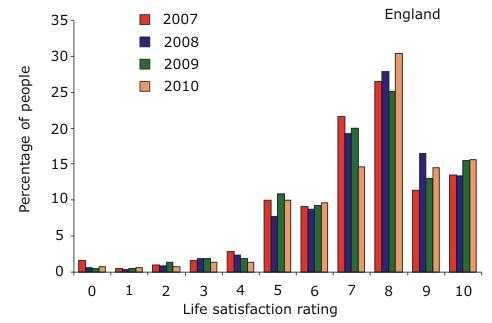

Defra began to measure wellbeing in 2007, looking both at an overall measure and at various domains of wellbeing suggested by research. But, when we were producing the figures the problem was that when people were asked to rate their wellbeing on a scale of 1-10, the average was always 7. As we went through the biggest post-war recession, which should have moved scores significantly, they stuck resolutely in the 7s – and indeed the score of 7.5 in 2010 was the same as in 2007.

Percentage of people reporting overall life satisfaction ratings, on a scale from 0 to 10, 2007 to 2010 (source: Defra)

What was more interesting was the breakdown – there was a very obvious social gradient on the indicators. The average for A/Bs was 7.7 and for D/Es 7.3. A minority of people had clearly had very low levels of wellbeing.

Does wellbeing affect policy making?

The real test for wellbeing is whether explicitly incorporating it into policy making makes governments do different things. The Treasury looked at this a few years ago (PDF, 579KB), and concluded the answer was no. Cameron singled out immigration, deregulation of licensing laws and an “irresponsible media and marketing” free for all as areas he felt policies had put growth above quality of life considerations. He also suggested Post Office closures and public sector top down targets had damaged wellbeing. Above all the new policy focus seems to shift to being “family friendly”.

Wellbeing elsewhere

Other jurisdictions have got there first – the Welsh Assembly Government is now committed to promoting the long-term wellbeing of the citizens of Wales. Back in England, three local authorities – South Tyneside, Hertfordshire and Manchester worked with the Young Foundation and LSE to see what happened when they tried deliberate interventions to promote wellbeing. Their report, The State of Happiness (PDF, 2.1 MB) sets out key areas where policy can more explicitly promote wellbeing. It’s quite a different list to Cameron's, including a greater emphasis on:

- supporting resilience and psychological fitness among children and young people

- parenting and good neighbour programmes

- tackling isolation among old people

- focussing on people’s experience of services

- planning and transport policies to promote exercise and reduce commuting times.

But yesterday's tasking of the ONS should mean that we are at the start of building a better understanding of how government action can and does affect wellbeing.

- Topic

- Policy making

- Keywords

- Public sector

- Public figures

- David Cameron

- Publisher

- Institute for Government