Rollercoaster or not, arguing over spending cuts is a pointless task

A row over how the OBR checks the figures.

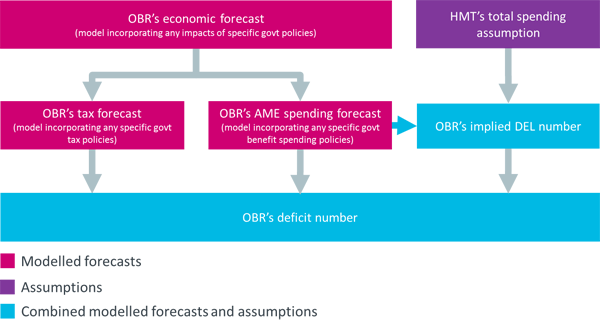

In his final Budget of this parliament, George Osborne revised down the £23bn surplus he promised in the Autumn Statement, to a £6bn surplus by 2019-20. Such change comes as no surprise – it allowed the Chancellor to ease the squeeze on public spending and avoid claims of a return to 1930s levels of spending. What’s more interesting is the row that erupted between the Chancellor and the Office for Budget Responsibility over where these cuts would fall and how the OBR checks the Chancellor’s figures.