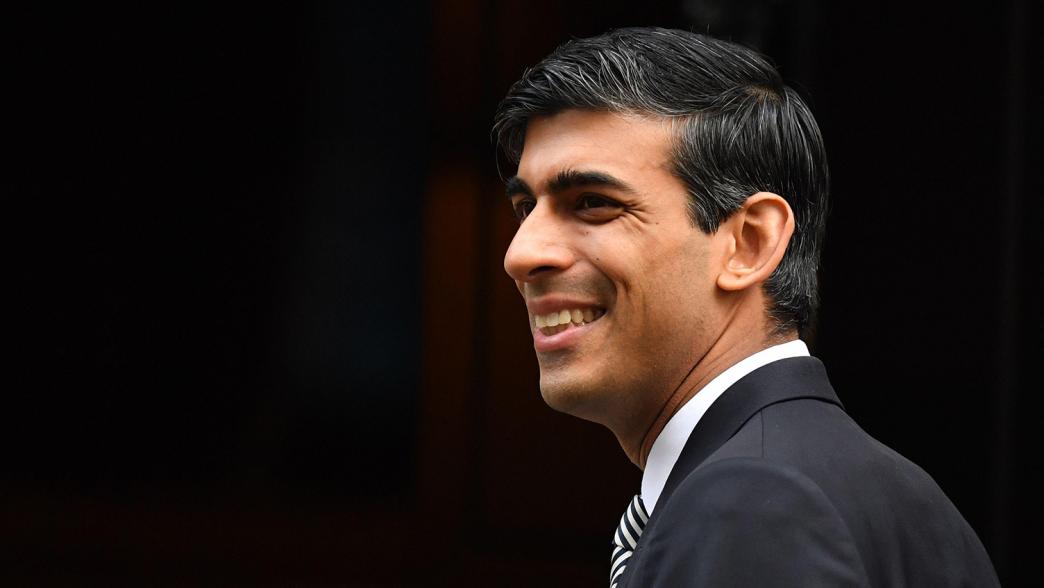

Rishi Sunak’s three Brexit headaches

Brexit is far from done – and Rishi Sunak's party stands in his way of being able to move on.

Unfortunately for the prime minister, Brexit is far from done – and his party stands in his way of being able to move on, argues Jill Rutter

It was never clear whether the Johnson “Get Brexit Done” coalition that delivered his majority in 2019 was more motivated by “Brexit” and the benefits they expected to flow from it, or the “done” promise as a nation wearied of three-and-a-half years of politics being dominated by the B-word. The bad news for the prime minister is that, nearly three years after the UK left the EU institutions and two years after concluding the Trade and Cooperation Agreement, Brexit and its fall-out is still very live.

In his brief time in office, Rishi Sunak has built on the improved mood music with European leaders that was probably the most notable achievement of Liz Truss’s brief tenure. His trip to COP27 was notable for chummy chats with Ursula von der Leyen and Emmanuel Macron, and later in the week he found time to be the first Conservative prime minister to attend the British-Irish Council and make contact not just with Nicola Sturgeon and (virtually) Mark Drakeford but also with the Irish Taoiseach, Micheal Martin.

But what is unclear is whether these improved “vibes” abroad turn into concrete changes which can ease UK-EU tensions.

Headache 1: How to land a solution to the Northern Ireland protocol – and survive

Northern Ireland secretary of state Chris Heaton-Harris pulled back from his commitment to call early elections to Stormont, and will need to legislate to get out of his legal duty to do so. He claimed that this was to give the negotiations more time, and various EU voices are suggesting that the two sides are close but with the added hint that the gap can be closed if the UK just moves a bit more.

If this were just a technical chat about customs arrangements and regulatory checks, there is undoubtedly a deal to be done. Quite where the landing zone is would depend on levels of trust and the EU’s tolerance for risk and view of the likelihood that the UK will significantly diverge from EU standards over time. That is the sort of deal a technocrat like Sunak would enjoy getting properly stuck into.

The problem is that his predecessor and his party have let the Protocol debate escalate well beyond technicalities. The position that the UK set out in the white paper in summer 2021 and the measures promised in the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill are not tweaks to make the Protocol work better but represent a wholesale ripping up and rewrite of the rules.

With those promises on the table, it is far from clear the prime minister has the latitude, even if he has the inclination, for settling for the much, much less that is likely to be offer on from the EU. Steve Baker warned that the ERG would be prepared to “implode” the government over a sell-out. Mark Francois claimed that Sunak had promised to ram the Protocol Bill through using the Parliament Act to see off the Lords if necessary. The DUP are still impaled on their maximalist demands.

It has always appeared that Sunak as chancellor – unlike some of his then colleagues – wanted to avoid a trade showdown with the EU. It is far less clear that he has the political strategy or clout within his party to sell any compromise.

Headache 2: Whether to press on with the Retained EU Law Bill

The Northern Ireland Protocol Bill is not the only inheritance from the Johnson/Truss administrations. The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill was the David Frost/Jacob Rees-Mogg answer to persuading their fellow secretaries of state to bother with revising the swathe of secondary legislation transferred into UK law through the 2018 Withdrawal Act.

The bill has come in for a lot of criticism, focussing mainly on the idea that all ex-EU law would be caught by its “sunsets” at the end of 2023. This created uncertainty. It risked creating bad law in a hurry with a lack of parliamentary scrutiny, wasting civil service and ministerial time and resource and a massive ministerial power grab. The devolved governments hate it as well. It risks complicating any solution to the Northern Ireland Protocol – and potentially retaliation from the EU if they think the UK is dropping standards.

But it is moving on. All the indications would suggest Sunak should make yet another U-turn on this (he doubled down on it in the leadership contest), not least because the government recently found an extra 1,400 EU laws down the back of the sofa – increasing the workload of this already mammoth undertaking by over a third. His business secretary has just announced yet another delay in a burdensome bit of divergence – the introduction of the UKCA mark to replace the EU’s CE in order to cut costs for business and remove potential disruption. But that would again mean taking on those in the party who rowed in behind Liz Truss and may blame him, not her, for her rapid downfall.

Headache 3: What to do with post-Brexit immigration?

There is an argument going on between Brexit supporters about whether the vote was a vote simply to control borders or a was also a vote to reduce the flow of migrants. Post-Brexit the number of migrants coming to the UK is still high – well above David Cameron’s tens of thousands, but it is also different. The new system has liberalised non-EU immigration, but clamped down on low skilled immigration – at a cost to the sectors that had grown to depend on it, as reflected in the comments by Lord Wolfson, who said this was not the Brexit he envisaged.

The row about immigration policy was the trigger for Suella Braverman’s resignation from Liz Truss’s cabinet: she wants a restrictive approach. The “growthers” wanted a policy that would allow the OBR to base its forecasts on an assumption that high numbers would continue. The replacement of Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng by Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt has not made this argument go away.

All these battles are about defining what Brexit means in practice. The referendum was fought without answering that question. Rishi Sunak now needs to decide whether to face down his party and put the immediate needs of the economy above Brexit purism.

- Supporting document

- brexit-coronavirus-economic-impact.pdf (PDF, 466.06 KB)

- Topic

- Brexit

- Country (international)

- European Union

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government