Campaigning politicians must not duck the issue of serious pressures in the public sector, says Dr Emily Andrews.

It is no secret that the Conservative Government has struggled to implement the promises of their last manifesto, particularly those around spending controls. As our Performance Tracker shows, the short-term belt-tightening measures that produced efficiencies in the early part of the last Parliament – staff cuts and wage control – are no longer working.

In the last six months, the Government has twice been forced into emergency action to stabilise services at or on the brink of failure: with emergency cash injections announced for 2,500 new prison officers at the end of 2016, and £2 billion for social care in the March Budget.

The biggest pressures

The data makes it clear where the biggest pressures facing the incoming government lie.

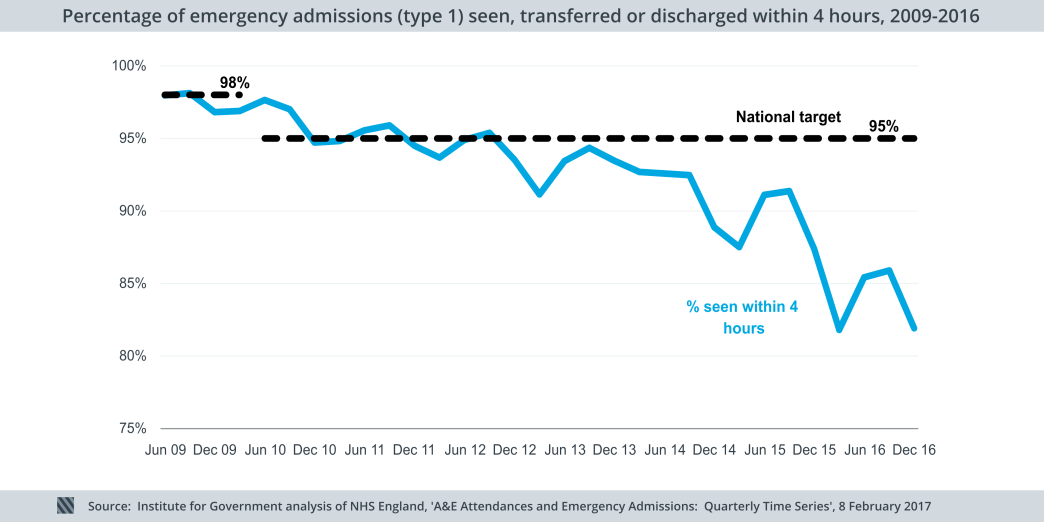

The last time the UK went to the polls (in a general election at least), 91% of people were seen at A&E within four hours. This is shy of the Government’s 95% target, which has not been hit since the end of 2012. Since then, despite record overspends and a cash injection at the last spending review, the number of people being seen within this four-hour target time has continued to fall, down to 81% at the end of last year.

Despite growing numbers of older people and working-age adults with long-term conditions, adult social care received a 6% spending cut between 2009/10 and 2015/16. This includes a funding boost from the Better Care Fund last year.

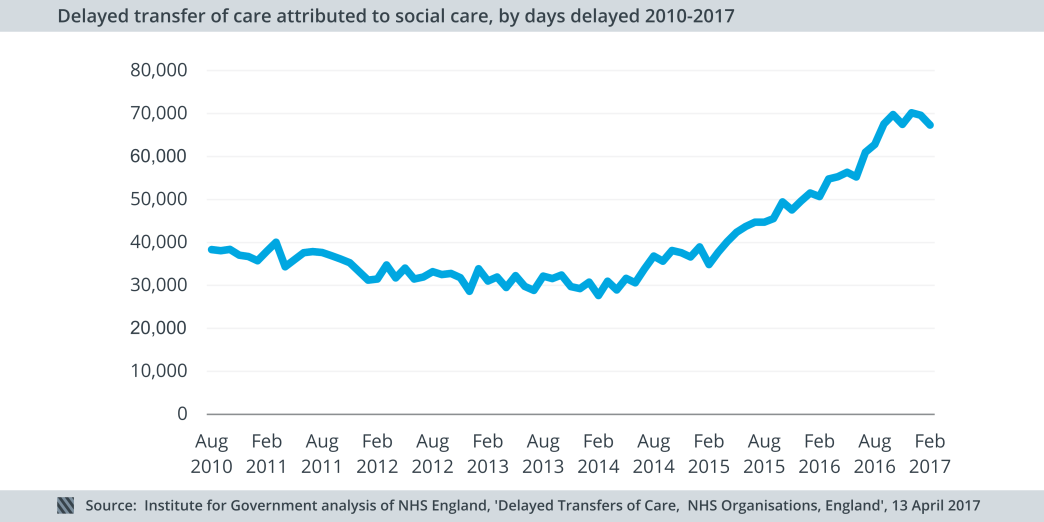

Yet delayed transfers of care – where people who are deemed medically fit for discharge remain in a hospital bed – continue to rise. The number of days delayed due to issues in social care has risen 51% since August 2015.

The extra £2 billion provided to the adult social care in the March budget may help tackle this immediate problem, but the Prime Minister herself has admitted that the Government does not currently have a long-term solution, to put the struggling sector on a sustainable footing.

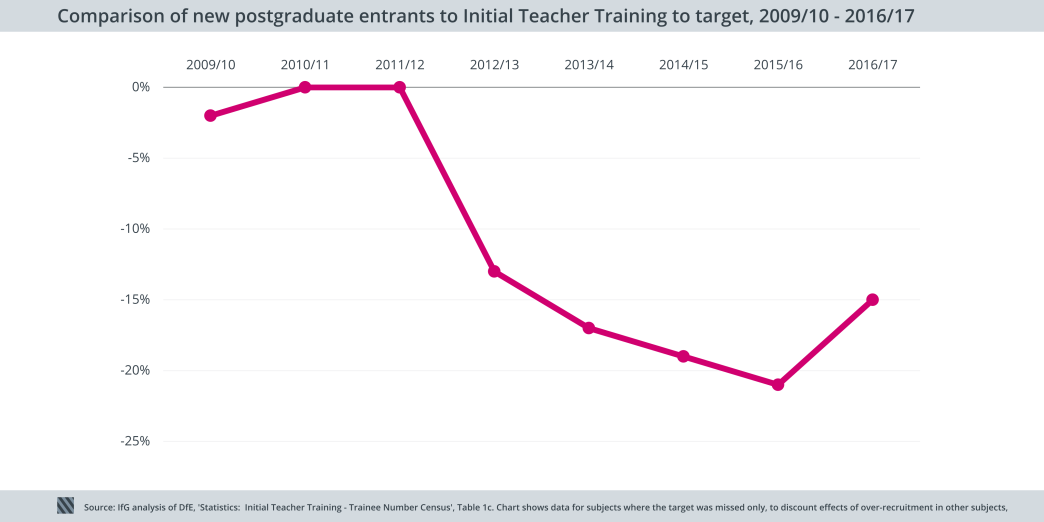

Schools continue to be comparatively well-funded but deeper problems are starting to appear. Last year, the Government’s target for teachers entering training was missed by 15%. Meanwhile, the number of teachers leaving state secondary schools has outstripped the number entering them, at a time when the number of secondary school pupils is set to rise. Schools will have to tackle these problems at the same time as a 6.5% reduction in per-pupil funding (up to 2019/20).

Facing up to the issues

So what are the options facing the current crop of ministers and aspiring ministers, as their election campaigns kick into gear?

Vague promises of efficiency and reform will not cut it this time round, after another two years of intensifying pressures in public services.

Vote-winning cash injection promises – softening the blow of the new schools’ funding formula perhaps – may look appealing. But failure to match the cash to genuine solutions could end up wasting money which the next government, whatever their colour, will not be able to spare. And we know the crisis, cash, repeat pattern of the last two years is unsustainable – financially and politically.

To square these circles – of demographic ageing, issues with the schools workforce, and a hefty Brexit implementation bill – the next Government will have to make difficult decisions.

All politicians owe it to the electorate to make it clear what those decisions are. It will be obvious whether this is happening. It will mean, for example, putting some specifics behind promises of ‘long-term strategy’ for social care: for example, do the parties intend to implement the recommendations of the Dilnot Commission, and if so how do they intend to pay for it?

Even better, parties should commit to submitting their spending plans to independent scrutiny through an ‘Office for Budget Responsibility for public spending’, to assess their realism. In a ‘post-truth’ age, it is vital that the public can trust that politicians’ claims about what they can achieve are reliable.

Politicians should use this election to gain a political mandate for specific, challenging reforms to tackle these pressures – or risk failing services and intensifying public mistrust.

- Supporting document

- Performance Tracker final web.pdf (PDF, 976.99 KB)