Policing pledges could spell trouble for the criminal justice system

The main parties’ pledges to increase police numbers may not be enough to effectively deal with crime, and could create issues further down the line.

The main parties’ pledges to increase police numbers may not be enough to effectively deal with crime, and could create issues further down the line, argues Benoit Guerin.

Crime and justice is one of the top three issues that could decide the general election, now only a few weeks away.

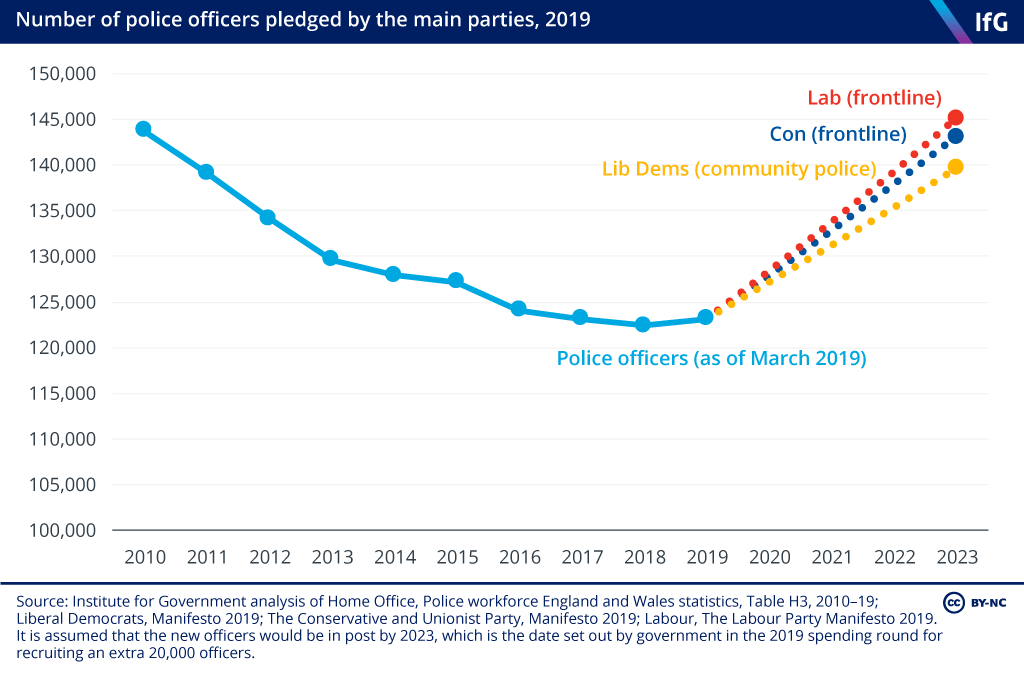

All the main parties have now set out new criminal justice policies in their manifestos, primarily focusing on policing. The Liberal Democrats have promised to spend £1 billion on community policing, enough to recruit two new officers per ward – around 16,500 officers in total – alongside a 2% pay increase for police officers. The Conservatives renewed their pre-election pledge to recruit an additional 20,000 police officers and announced tougher sentences for serious crimes. In response, Labour has promised 2,000 more frontline officers than the Conservatives, alongside reforms to police funding.

New officers must be deployed effectively if they are to tackle increasingly complex crimes

All the main parties have committed to increase the number of police officers, mainly on the frontline. A 20,000-officer increase would see numbers return to around 2010 levels, when there were 143,734 officers.

But if they are to effectively tackle crime, these officers should be deployed where they can do the most to prevent or reduce crime. Having more "bobbies on the beat" may reassure the public, but the evidence suggests its impact on crime levels is limited.

This is partly because police work has shifted away from dealing with traditional ‘street’ crime. Criminal activity is moving online, while the number of complex, serious and organised crimes – from human trafficking to sexual crimes against children – has also increased. Between 2009/10 and 2018/19, the police recorded a 259% increase in child sexual exploitation and abuse crimes, from 17,402 to 62,409 cases.

The police now also have to process an ever-growing amount of digital evidence. A single mobile phone can generate an average of 35,000 pages of evidence, while industry referrals for online child sex abuse images in the UK have gone up by more than 10 times (997%) between 2012 and 2018, from 10,384 to 113,948.

This places a huge burden on forces often ill-equipped for the challenges of the digital age, and along with responding to more complex and serious crimes, puts serious pressure on police time. Since 2015, the average length of time taken to charge a crime increased from 10 to 23 days.

Dealing with these problems requires more than just officers on the streets. Indeed, the Home Office has already clarified that some of the Johnson government’s promised 20,000 officers would be deployed in serious and organised crime or counter-terrorism units, rather than local forces.

An alternative way to deploy a new intake of police officers could be to boost the number of officers in support functions – as has been the case in recent years – to ensure that investigators can focus on solving crimes. Investing in digital capability, mentioned in the Labour and Conservative manifestos, could also help to investigate online crimes. For example, additional specialist training could enable investigators to deal with cases that rely on digital evidence, including online child sexual abuse.

The next government will need to consider the impact of extra police officers on courts and prisons

Manifestos matter – but the promises they contain are not always well thought through. Police pledges are a case in point.

More police means more criminal charges; more charges means the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) prosecutes more cases, which in turn increases the time required in criminal courts to hear them. Some cases will result in prison sentences, placing additional demands on prisons.

Any increases in police numbers, therefore, needs to be backed up with funding for other parts of the criminal justice system – yet there are few plans in the manifestos published so far to do so.

Labour has vowed to stop court closures and cuts to Ministry of Justice staff working in them, while the Conservatives have pledged extra funding for the CPS – but there is nothing explicit on criminal courts themselves. Similar concerns apply to prisons, where no extra funding is explicitly mentioned, although the Conservatives promise an additional 10,000 prison places, the Liberal Democrats vow to recruit 2,000 more prison officers and Labour promise to bring the number of prison officers back to 2010 levels.

As our Performance Tracker 2019, produced in partnership with CIPFA, shows, there are concerns with the quality of the justice system, and criminal courts and prisons in particular. Prisoner-on-prisoner assaults have more than doubled since 2009/10 to 24,541 incidents per year, while assaults on prison staff tripled to 10,311 in the same period. It is vital to ensure that quality or safety do not deteriorate further as a result of further pressures stemming from greater police activity.

All the main political parties have competed on raising police numbers, but they must look beyond "bobbies on the beat" to deploy new officers most effectively and consider the impact of more police on the whole criminal justice system. Promising more police officers is effective during an election campaign, but it is no panacea for crime and justice.

- Supporting document

- performance-tracker-2019.pdf (PDF, 4.23 MB)

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Criminal justice General election

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government