Making prisons safer requires more than a one-off cash boost

Rory Stewart’s 10 Prisons Project was successful – but replicating it across the prison estate will require additional spending.

Rory Stewart’s 10 Prisons Project was successful – but replicating it across the prison estate will require additional spending, argues Graham Atkins.

Last August, the then prisons minister Rory Stewart pledged to resign if he could not “substantially” reduce violence and drug use in 10 prisons. These prisons – all category B or C mid-security male prisons – were selected because they had “acute problems” with drug use, violence and building maintenance. Though light on specifics, Stewart pledged that he would consider success to be a reduction of 10–25% within a year.

Stewart chose to leave the government for entirely different reasons – declaring that he would not serve under Boris Johnson – before he reached his self-imposed deadline. One year on from his pledge, the Ministry of Justice has published its analysis of the project – and it suggests that Stewart’s high stakes accountability gamble would have paid off. He would not have been forced to resign.

Rory Stewart’s 10 Prisons Project improved prison safety

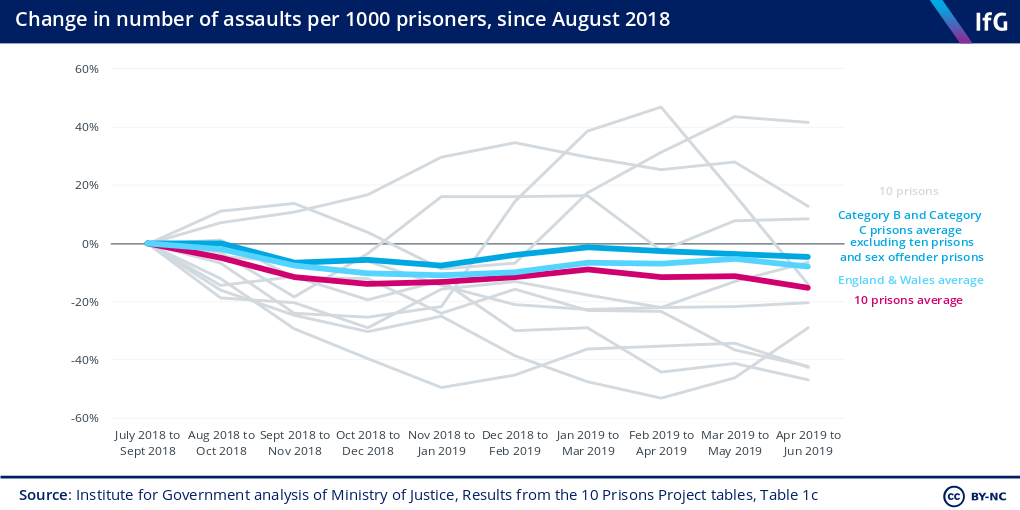

The analysis shows reductions in assaults and positive drug tests in these 10 prisons. After Stewart’s project began last August, the assault rate – the number of assaults per 1,000 prisoners – fell faster, on average, in the 10 prisons than in all prisons or comparable category B and C prisons.

The 15% decline in the 10 prisons – compared to a 5% decline in comparable category B and C prisons – represents Stewart’s pledged “substantial reduction”, but the rate of assaults increased in three prisons: Leeds, Nottingham, and Wormwood Scrubs.

The percentage of positive results from random mandatory drug tests also fell in the 10 prisons, but it is hard to tell whether this improvement is attributable to Rory Stewart’s project because the Ministry of Justice did not provide figures for drug tests in other prisons

Improvements were based on significant increases in staff and capital expenditure

The reductions in violence were based on large increase in resources. The 10 prisons in the project received at least £10 million (m) of additional funding over the last year. The number of prison officers in the 10 prisons rose faster than in all prisons following the government’s £291m cash injection, announced in the 2016 Autumn Statement, to boost officer numbers. The number of prison officers in the 10 prisons increased by 31.1% on average after December 2016 compared to an average 26.1% increase in all prisons. After February 2019, the 10 prisons also received additional experienced staff to coach new prison officers.

At the same time, capital expenditure in the 10 prisons – spending on physical assets like x-ray security scanners and building repairs – rose from £0.1m in the last six months of 2017/18, to £3.8m in the last six months of 2018/19, after the 10 Prisons Project began. The government does not provide figures on how capital expenditure changed in other prisons, but we do know that the overall capital spending on prisons and probation fell from £83.4 to £68.3m between 2017/18 and 2018/19. This suggests that the increase in capital spending in the 10 project prisons was bigger than in other prisons

This government’s prison promises will need to be backed by spending review commitments

While this progress is encouraging, recent government announcements – recruiting 20,000 more police officers, providing £85m for the Crown Prosecution Service to prosecute criminals, and promising to build 10,000 extra prison places – imply that the number of prisoners will increase faster than is currently projected by the Ministry of Justice.

Assuming the government remains committed to “a world-leading prison estate to keep criminals off our streets and turn them into law-abiding citizens”, as Justice Secretary Robert Buckland said last month, then it will need to allocate additional money to prisons in order to replicate the improvements seen in the 10 project prisons.

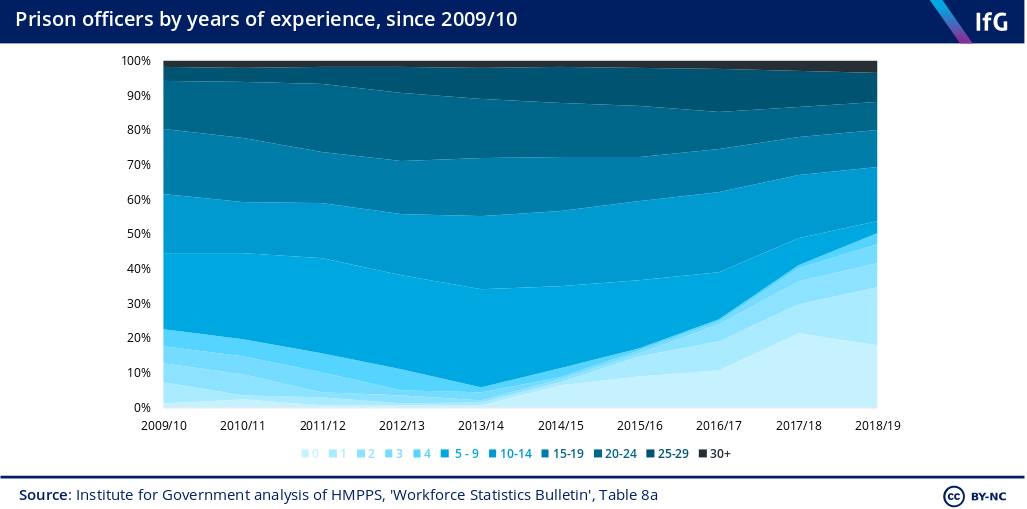

The government has announced it will give £100m to prisons this year to improve security in this year’s spending round – but to improve prison safety it will need a recurrent increase in spending. The government needs to provide funding to pay for additional staff in the medium-term, not just to buy new equipment next year. The Ministry of Justice’s own research suggests that the number of skilled prison officers has the biggest impact on reducing prison violence. Prison officer leaving rates – which have increased since 2014/15 – need to be addressed. Between 2009/10 and 2018/19, the share of prison officers with fewer than five years of experience increased 28 percentage points, from 22% to 50%.

Improvement across the prison estate requires more than short-term cash boosts

If he were still in post as prisons minister, then Rory Stewart would have reason to celebrate – and would not need to resign. But offering one-off cash injections to bolster security is not a long-term solution to drug use and assaults across the prison estate – the latter of which has more than doubled over the last five years. Next year’s spending review is an opportunity to demonstrate that the government is serious about the challenge, and committed to improving prison officer retention. If not, Stewart’s successor will soon find themselves in no position to pledge improvements in England and Wales’ prisons.

- Supporting document

- Prisons briefing final.pdf (PDF, 210.78 KB)

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Criminal justice Public spending

- Department

- Ministry of Justice

- Publisher

- Institute for Government