Polling by the research and polling consultancy ComRes gives an indication of how well MPs think different departments respond to their requests for information. Joe Randall examines MPs’ feedback, using data published for the first time in Whitehall Monitor 2015, with thanks to ComRes.

An important part of any department’s work is responding to inquiries from politicians, journalists and the public. Whitehall Monitor works with data on three different types of these information requests, assessing how well departments do in responding to parliamentary questions, Freedom of Information requests and ministerial correspondence.

Now, with data provided by the research and polling consultancy ComRes, we can also explore how well some of the customers of this service – MPs – think Whitehall departments are doing.

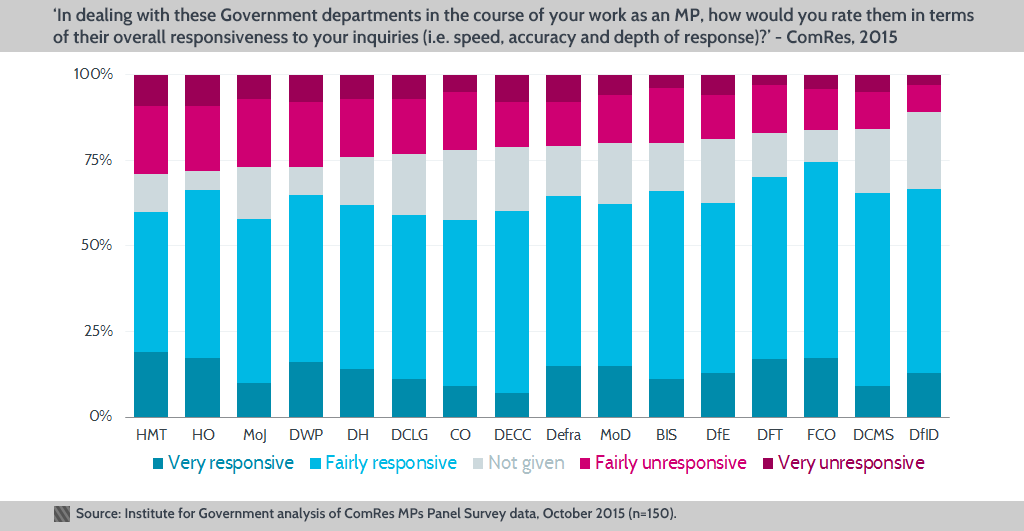

As part of their regular surveys of MPs, ComRes asks: ‘In dealing with these government departments in the course of your work as an MP, how would you rate them in terms of their overall responsiveness to your inquiries (i.e. speed, accuracy and depth of response)?’ MPs are asked to state whether they feel a named department is ‘very responsive’, ‘fairly responsive’, ‘fairly unresponsive’ or ‘very unresponsive’.

On one measure, MPs consider HM Treasury and the Home Office to be the least responsive government departments.

Using one measure, in 2015, HMT and HO were considered the least responsive departments by MPs. These departments were considered ‘fairly unresponsive’ or ‘very unresponsive’ to inquiries by 29% and 28% of MPs respectively. This is not particularly surprising given that these departments came in 14th and 17th place (out of 19) in our overall ranking of departments’ responses to information requests in Whitehall Monitor 2015. FCO was considered to be the most responsive department – 74% of MPs surveyed considered it either fairly or very responsive to their inquiries, though in our overall rankings, it placed only 6th highest.

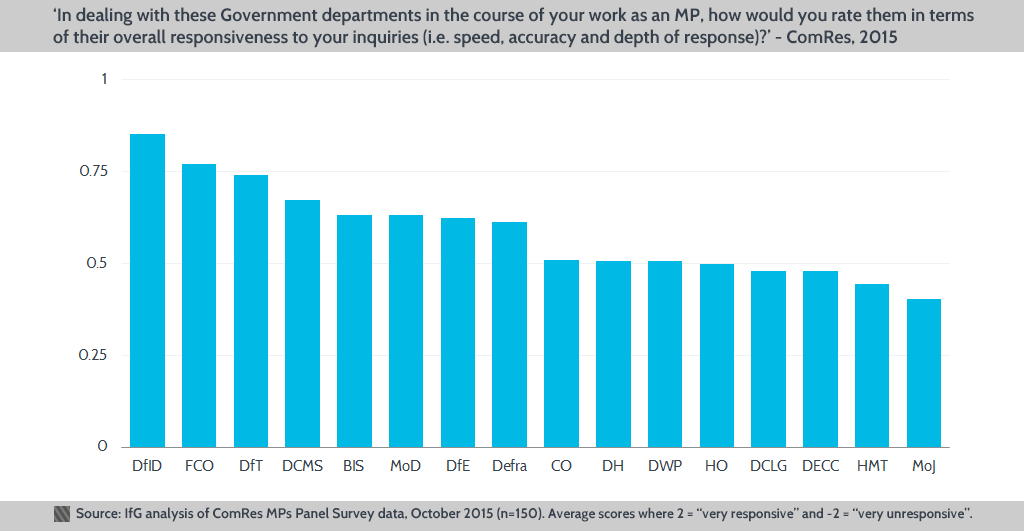

On another measure, MoJ comes out as the least responsive department, with DfID leading the pack.

If we use a scoring system of MPs’ different responses – where ‘very responsive’ gets a score of +2, ‘fairly responsive’ +1, ‘fairly unresponsive’ -1 and ‘very unresponsive’ -2 – we can also assess the strength of MPs’ feelings about departments’ responsiveness to requests for information, over time.

Using this measure, we can see that all departments in 2015 received positive ratings overall, although there is some fairly significant divergence between them. DfID was judged by MPs to be the most responsive department in 2015 with an average score of 0.85, while MoJ came bottom of the rankings with an average score of just 0.4.

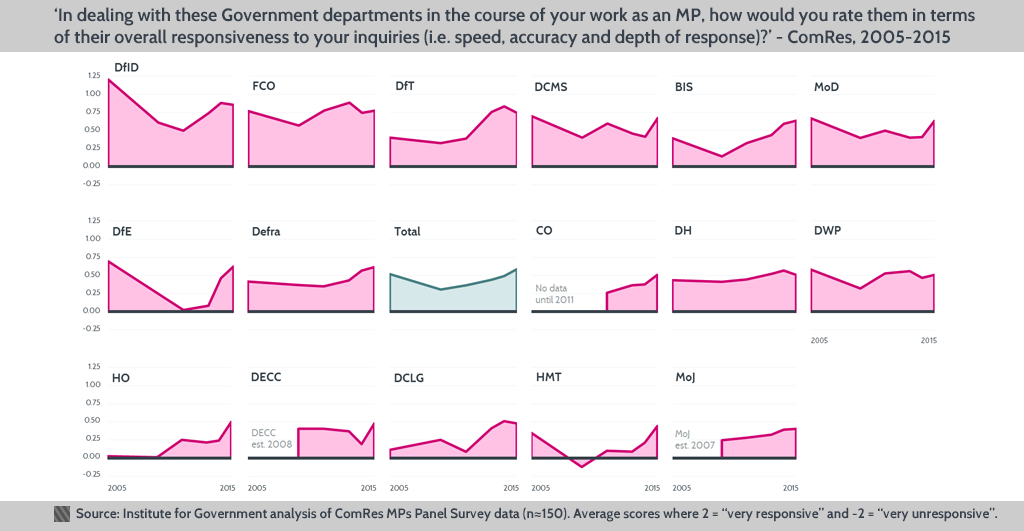

Using the scoring system, DfID and the Foreign Office have been ranked by MPs as two of the most responsive departments consistently since 2005.

Using the scoring measure over time, DfID, FCO and DfT come out on top as the departments felt by MPs in 2015 to be most responsive overall. While all three have been relatively high-scoring since 2005 when this dataset begins, DfT has shown the largest improvements since 2005. The three departments that scored lowest by this measure in 2015 were DCLG, HMT and MoJ.

Many departments have received relatively stable scores from MPs over time. Two exceptions to this are DfE, whose score fell sharply in 2011, but (as we noted in Whitehall Monitor 2015) seems to have improved its responses to information requests since then; and HMT, which in 2011 became the only department to receive an overall negative rating from MPs.

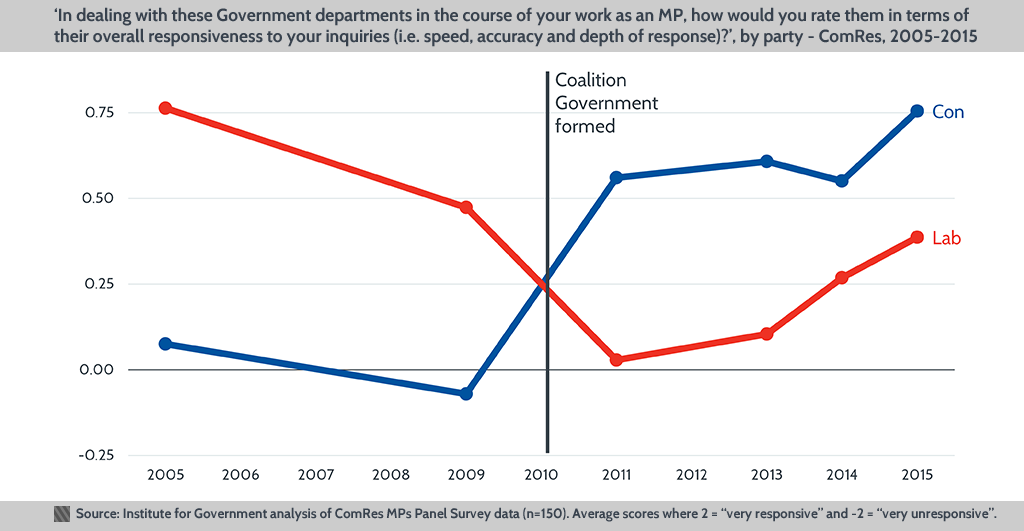

MPs are partisan – those from parties in government tend to be far more positive about departments’ responsiveness than those from opposing parties.

One of the limitations of using perceptions data to assess departments’ responsiveness is that the sample comprises a highly partisan set of respondents – MPs. Those from parties who form the government of the day tend to rate departments’ responsiveness much more highly than those from opposing parties. There were large shifts in Conservative and Labour MPs’ opinions about departments’ responsiveness after the Coalition Government assumed office.

In the Institute's Ministers Reflect interviews, some ministers – such as former Education Minister Tim Loughton – spoke about this shift, and the interesting dynamics involved in MPs on their own side scrutinising the work of their own government through information requests:

‘So we went in and all of a sudden you had to transform your job because your job had been (1) working out what you wanted to do in education, children’s services in my case or whatever; but (2) opposing the Government and scrutinising the Government. All of a sudden you become the Government. Some of our colleagues found it quite difficult to change that mind-set, not least when I found myself getting Freedom of Information requests from people on your own side afterwards, and I had put down an awful lot of Freedom of Information requests to the Government. All of a sudden you’re the Government. So you’ve got to completely reverse your role and reverse your mind-set.’

Despite these limitations in the data created by political shifts, the ComRes data adds an interesting additional dimension to our work on information requests – showing the opinions of an extremely important customer, MPs.