The Government does not understand why demand for children’s social care is rising

The DfE will not be able to help children in need if it fails to understand the reasons why demand for children’s social care is rising.

Graham Atkins argues that the Department for Education will not be able to help children in need if it fails to understand the reasons why demand for children’s social care is rising

Yesterday’s National Audit Office report could hardly have been more blunt in its criticism of the Department for Education. The Department, says the NAO, does not understand the rising levels of demand and activity in children’s social care and should conduct additional research to make sense of this. Given the magnitude of the problem, we agree with the NAO’s recommendation.

Inevitably, if the Department does not understand why demand is rising then it is letting down some of the children most in need of support. And there will be wider consequences too. If demand continues to rise, then social worker caseloads and council spending will increase. This will intensify recruitment problems as well as reduce funding for other pressured council services such as libraries, food safety, and road maintenance.Councils are assessing more cases, protecting, and caring for more children than they were in 2010

So where has demand increased?

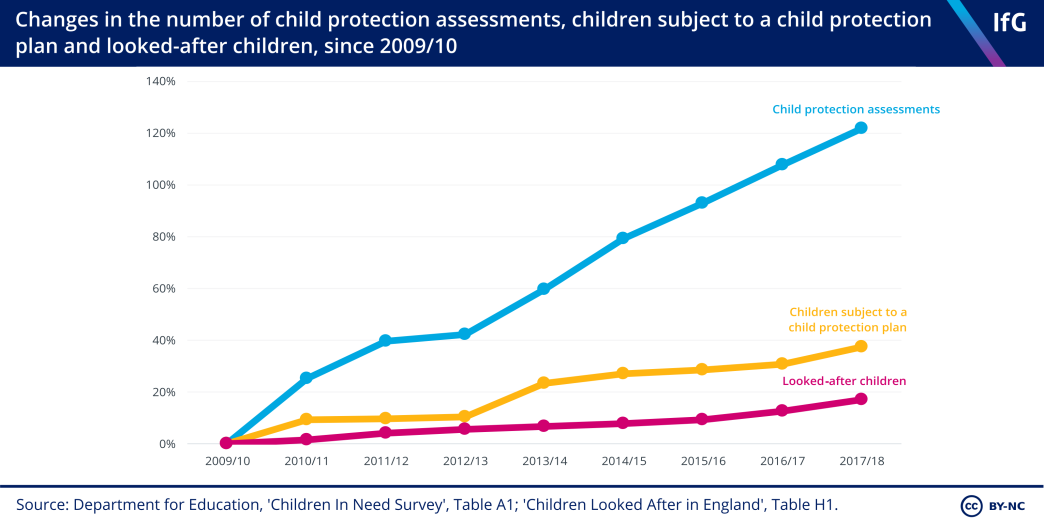

The costliest activities in children’s social care – child protection assessments, supporting children on child protection plans, and children-in-care – have increased rapidly since 2010.

Child protection assessments – where a team of social workers, teachers and police officers assess whether a child is at risk of significant harm – have increased particularly rapidly. Councils undertook 122% more assessments in 2017/18 than they did in 2009/10.

Referrals to children’s services – an indicator of demand - also grew, though not as quickly, increasing 9% over the same eight years.

Further efficiencies aren’t a solution to managing rising demand for children's social care

To date, the department has mostly relied on councils making efficiencies in children’s social care to manage rising demand. And, so far, this has just about worked. The quality of children’s social care – as far as can be measured – has not fallen dramatically. But this approach can’t be pushed further without damaging consequences.

Our Performance Tracker – produced in partnership with the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy – highlights those consequences. High social worker turnover and rising vacancies – which increased from 3,610 to 5,820 over the last four years – have left councils more reliant on agency social workers. The agency worker rate – the percentage of social workers not permanently employed by councils – increased four percentage points over the last four years, and councils near doubled their spending on agency staff between 2012/13 and 2016/17. Further increasing social workers’ workloads risks intensifying growing recruitment problems and will see councils spending more on agency staff to make up a shortfall of permanent social workers.

There are also warning signs in child protection. The number of children going back onto a child protection plan – re-entering child protection after their problems had been considered resolved – has steadily increased since 2009/10, from just under 6,000 in 2009/10 to almost 14,000 in 2017/18. At the same time, the timeliness of child protection reviews – whether social workers are seeing children on child protection plans within statutory timescales – declined from 97% to 91%. Both suggest social workers are struggling to keep up with demand.

The Department for Education must understand why demand and activity are increasing

If further efficiencies cannot be made and the Government does not reverse its plans to reduce grants to councils, then the Department must explore how it can reduce demand – and to do this it needs to understand why referrals and activity are increasing.

The Department’s initial research suggested a range of explanations from population growth, increasingly complex needs, and a rise in unaccompanied asylum-seeking children, but the NAO concluded that this work was “analytically limited, not comprehensive and contains no prioritisation of factors”.

Worryingly, the NAO does not find evidence that preventative services, one part of the Department’s 2016 reforms, reduce demand, while an independent evaluation of the Department’s own Innovation Programme similarly found limited evidence that projects designed to reduce looked-after children and children-in-need have done so.

The Department has responded by commissioning further research on the relative drivers of demand, but this does not go far enough. The next step for the Department is to commission research on how, if at all, councils can best reduce demand. The least that the taxpayer can expect from Whitehall is that government departments understand the problems they’re grappling with.

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Social care Local government

- Department

- Department for Education

- Publisher

- Institute for Government