Extra money alone will not tackle rough sleeping

The Prime Minister should make rough sleeping a priority for the whole of government.

Theresa May's announcement of extra funding for the Government’s rough sleeping strategy is welcome, but Tom Sasse argues the Prime Minister should make it a priority for the whole of government

One eye-catching proposal from the Conservative Party Conference was Theresa May’s plan to use revenue from stamp duty increases for those who do not live or pay taxes in the UK to help end rough sleeping by 2027. While extra money will help, rough sleeping must be a priority across the whole of government, not just one department, if government is to make serious progress. The prime minister should establish a powerful expert unit to coordinate policy across departments - and set it an interim target for halving the number of rough sleepers.

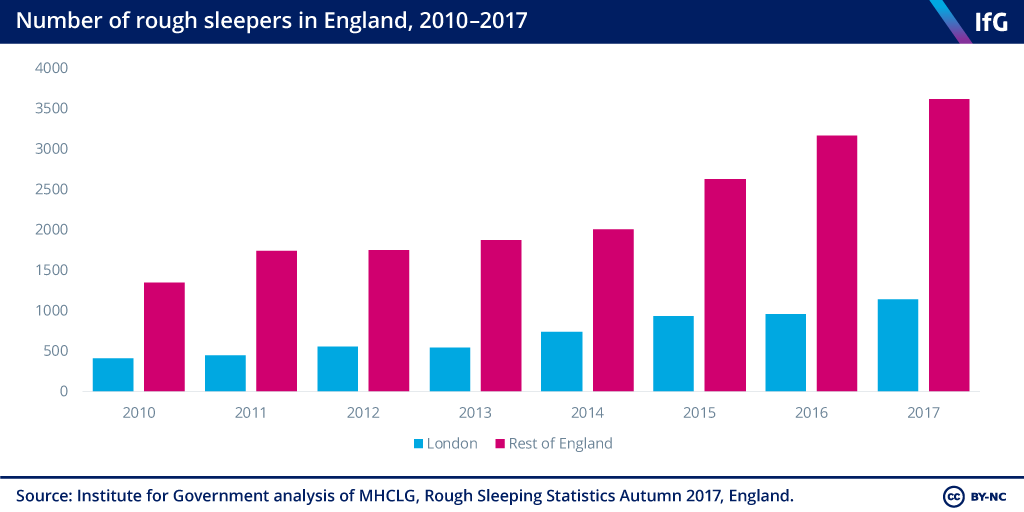

Rough sleeping fell in the 2000s but it has been rising since 2010

Tackling rough sleeping was a priority for New Labour when it entered government in 1997. Rough sleeping was a growing problem that had begun to receive political attention on both sides (the Major Government had done work to improve how it was measured). Building on this, Tony Blair set up the Rough Sleepers Unit in 1999 and tasked it with reducing the number of rough sleepers by two thirds by 2002. The target was met a year early and the number of people sleeping rough in England remained flat for the rest of the decade. But since 2010, rough sleeping has risen sharply. There were almost 3000 more rough sleepers in England last year than in 2010. This has been driven by several factors including the financial crash, welfare reforms, cuts to social housing supply and an increase in Eastern European immigration.

More money will help meet extra demand

In August, the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) published a new Rough Sleeping Strategy. It announced the 2027 target and committed £100 million to housing and prevention programmes to help meet it. This is not new money from the Treasury: it is existing funding or money re-prioritised from elsewhere in its the ministry’s budget. It is not yet clear how much the prime minister’s stamp duty change will bring in because the exact level of the increase will be put out to consultation. But given MHCLG’s tight finances, extra money will certainly help it to meet unprecedented levels of demand.

But reducing rough sleeping must be a priority for the whole of government

However, extra money alone will not end rough sleeping. The lesson from the early 2000s is that three things created impetus across the whole of government. First, strong coordination. Departments launched a wide range of initiatives - extra hostel beds; new alcohol, drug and mental health specialists; new outreach services; targeted programmes for those leaving care, prison and the armed forces – but they were coordinated by the powerful Rough Sleepers Unit, a group of experts assembled from Whitehall and the homelessness sector. Policies on housing, health, welfare, police and crime all pulled in the same direction.

This has been missing in recent years. Government initiatives on homelessness and rough sleeping have been “at best not joined up, and at worst contradictory”, according to the Communities and Local Government Select Committee. The Department of Health created a fund to improve hostel accommodation for the homeless but soon after the Department for Work and Pensions capped the housing benefit hostels can receive, making some unviable, for example. One reason for weak coordination is that MHCLG has suffered a from a stripping out of expertise on homelessness and rough sleeping. Most of its key staff left in the space two or three years after 2010 - and turnover has remained high ever since. In order to ensure it can coordinate efforts to tackle rough sleeping effectively, MHCLG should set up an expert unit, akin to the Rough Sleepers Unit.

Second, Blair’s backing was key to the success of the Rough Sleepers Unit. During the Coalition Government homelessness was less of a priority, which is one reason MHCLG struggled to influence other departments. By making rough sleeping a prime-ministerial priority once more, Theresa May has made a good start. But Number 10 must follow up her announcement with continued engagement behind the scenes to ensure that rough sleeping is factored into policy discussions across Whitehall – from the rollout of Universal Credit to social housing reform to changes to mental health provision.

Finally, in 1999 the Government had an ambitious target - cutting rough sleeping by two thirds in three years – which it achieved a year early. The target was a catalyst. It gave the people working on rough sleeping a sense of personal responsibility and an incentive to achieve results quickly. The government’s current target for eradicating rough sleeping is nine years away. This creates a lack of accountability: on average, senior civil servants stay in post less than two years and many policy officials less than that. If the prime minister wants to focus minds, she should set an interim target for halving the number of rough sleepers.

- Topic

- Policy making

- Keywords

- Housing

- Administration

- May government Blair government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government