The domestic politics of negotiating Brexit: EU money?

How much we contribute and receive from the EU dominated the referendum campaign and aftermath

How much we contribute and receive from the EU dominated the referendum campaign and aftermath. Oliver Ilott sets out what the UK receives from the EU, which sectors and regions benefit the most and how this will affect the ability to strike a UK-wide approach to negotiations.

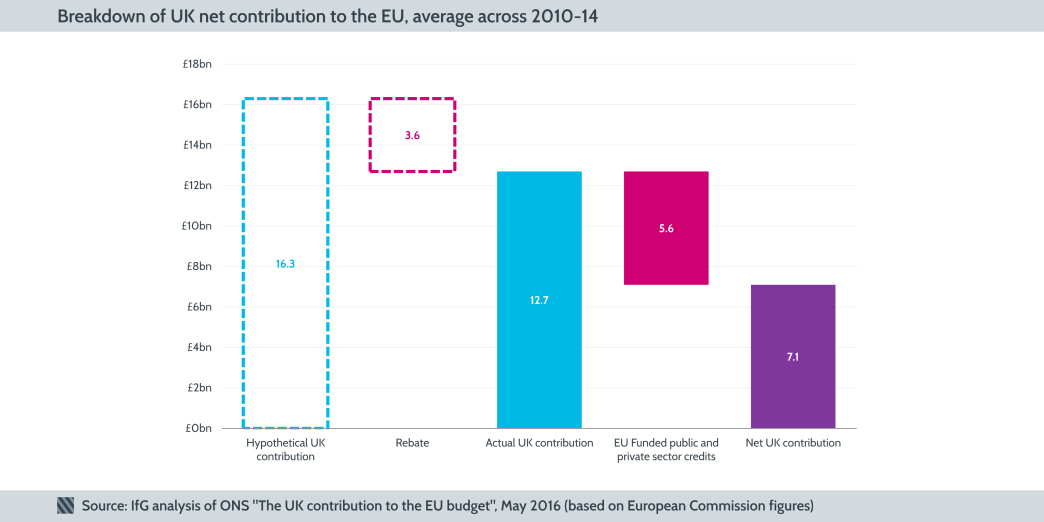

The UK makes an average net contribution to the EU of £7.1bn.

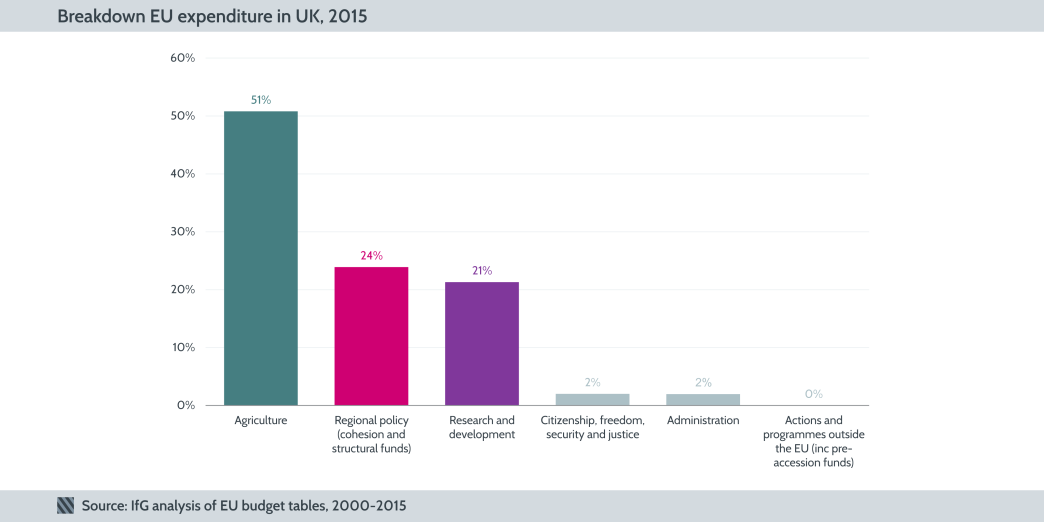

The majority of the EU’s spending in the UK goes on supporting the agricultural industry.

In 2015, the EU’s budget for spending in the UK was €7.5bn (around £6.2bn – note that this refers to a single year, not the multi-year averages referenced above). 96% of these funds were spent on three areas: agriculture (51%), regional policy (structural and cohesion funds) (24%) and research and development (21%).

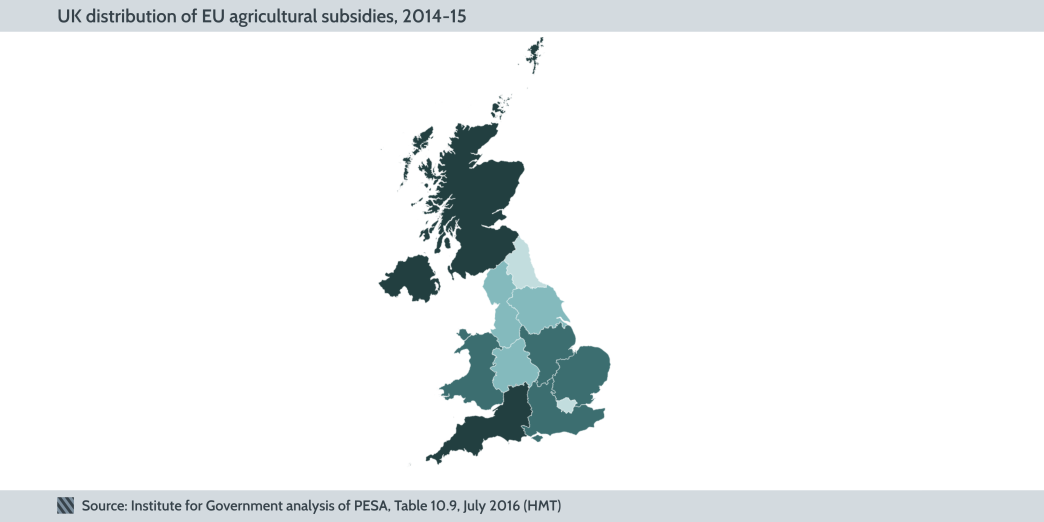

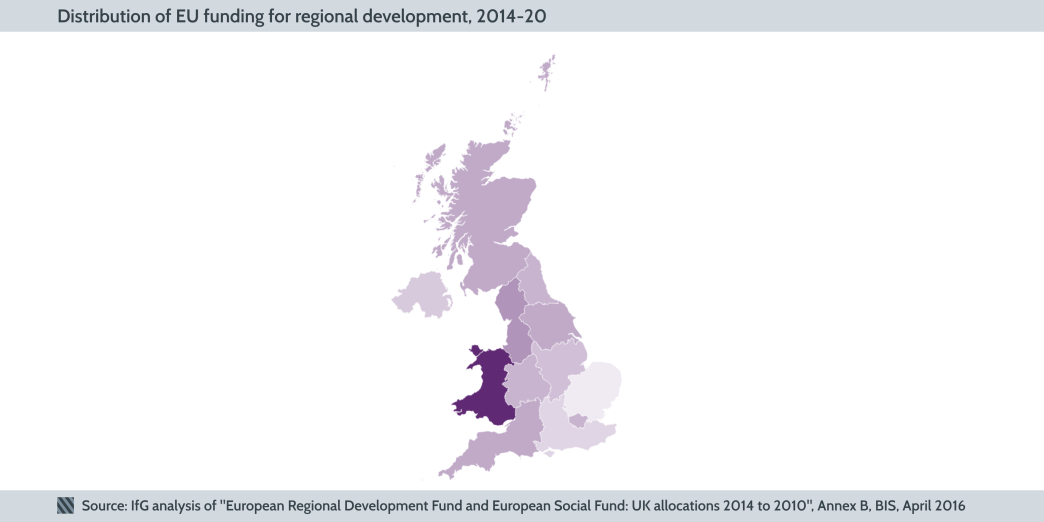

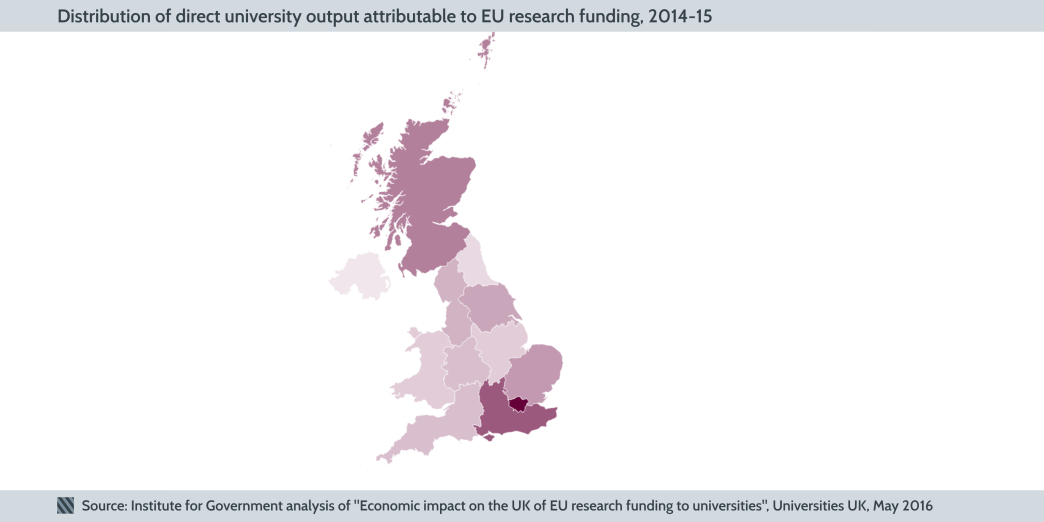

Different regions benefit differently from these EU funding streams.

In agriculture, farmers in Scotland, the South West of England, and Northern Ireland benefit the most from EU funds. Direct payments to these areas totalled £400m, £343m and £310m respectively in 2014-15.

The UK-EU negotiation is not going to be a simple two-way negotiation, but will involve managing multiple negotiations at the regional, domestic and international level – many at the same time. Any Brexit deal will have to be acceptable not just to the EU and member states, but to the UK public and UK interest groups. Managing these domestic politics will be complicated by the fact that different regions and sectors have very different sets of priorities in terms of what they would like to get out of any deal struck with the EU.

- Topic

- Brexit Public finances

- Keywords

- Public spending Withdrawal Agreement

- Country (international)

- European Union

- Administration

- May government

- Department

- Department for Exiting the European Union

- Publisher

- Institute for Government