Civil service cuts should be informed by proper workforce planning

Rhys Clyne says that the government should work out the skills and experience it need from the civil service

Rhys Clyne says that the government should work out the skills and experience it needs before deciding how to meet the Treasury's new target for civil service cuts

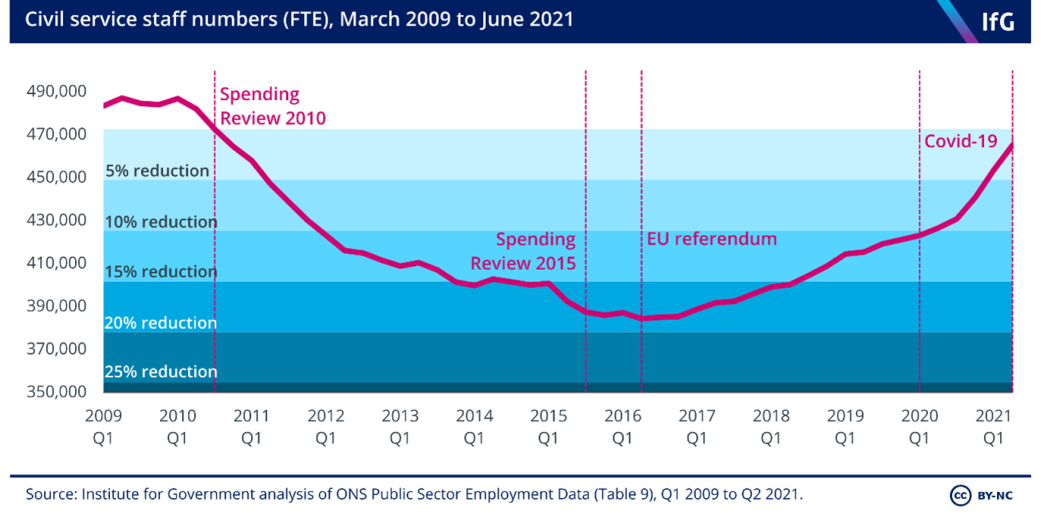

With the UK now settling in to its new relationship with the EU and the worst of the pandemic hopefully over, ministers want to reduce the size of the civil service. The spending review set out the government’s plans to reduce headcount to pre-Covid levels by 2024-25.[1] That means cutting around 45,000 jobs. Removing some of the new roles from the past five years makes sense – many of those created at the height of the pandemic or to prepare for Brexit will not be needed in the future – and the target is more modest than a reduction to pre-Brexit levels, as had been reported.[2]

But an arbitrary target is not the best way to manage the government’s workforce. Now that the chancellor has set one, ministers and officials must understand the workforce they have, and identify the workforce they will need in the future, before making decisions about where the axe should fall.

Poorly targeted cuts will undermine the government’s post-Brexit and Covid responsibilities

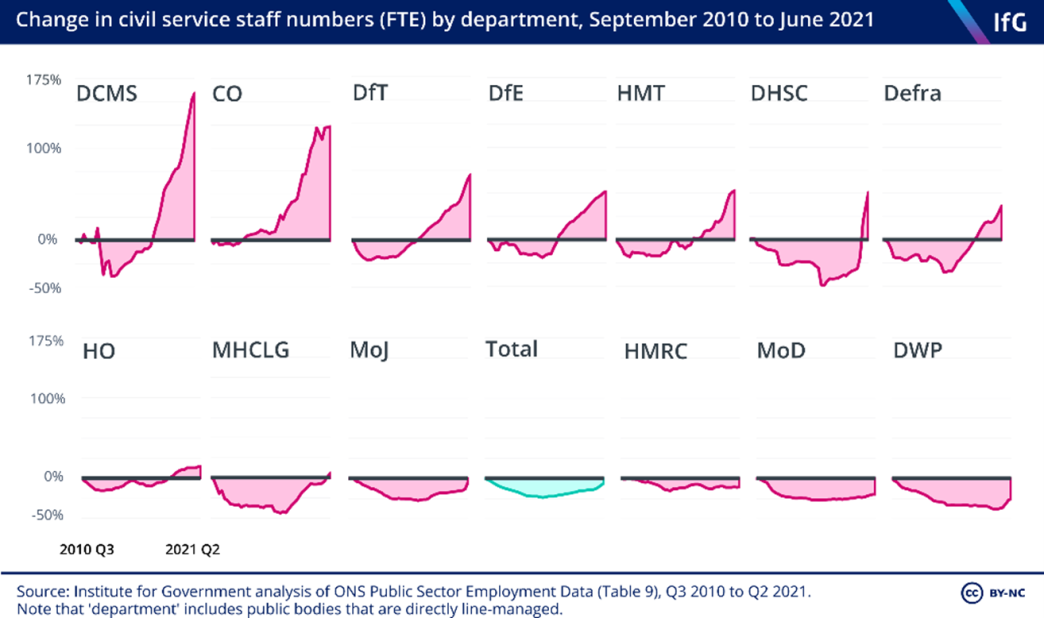

Since the EU referendum the civil service has grown by 21%, reversing most of the cuts made by the 2010-15 coalition. This increase can largely be attributed to Brexit and Covid. Defra has more than tripled in size since the referendum, reflecting the extent of its preparations for and responsibilities after Brexit. DHSC has more than doubled since 2019, with staff brought in to support the pandemic response, including the test and trace programme. Some of these roles will not be required on a permanent basis.

However, that does not mean the growth in each department can just be reversed. Brexit has created new, permanent resource pressures. The government set up the Department for International Trade. The Home Office has implemented a new immigration system and must now process visas for EU citizens wanting to work here, as well as from the rest of the world. Defra is designing an agricultural support regime to replace the EU’s common agricultural policy. Arms’ length bodies such as the Competition and Markets Authority and the Health and Safety Executive have taken on new functions, though not all public bodies are counted as civil servants. The government’s post-Brexit responsibilities will require permanent civil service resource to administer, regardless of whether ministers consider Brexit to be “done”.

Covid exposed the risk of running departments with bare minimum staffing and will alter the role government plays in future. The recent joint report by the science and technology and health and social care select committees into lessons from Covid argued this was true for the Civil Contingencies Secretariat, which “did not have adequate resources” to prepare for and respond to the pandemic.[3] But in departments across Whitehall ministers should work out how much capacity they need to respond to future crises before deciding where to cut. Allowing departments to ‘run hot’ may save money in the short-term but it creates expensive risk to resilience in the long-run.

Cuts will not generate major savings and could end up costing more

The spending review was more generous than anticipated but the government is still under significant pressure through a combination of Covid recovery and ambitious priorities. So it is understandable that ministers are looking to save money. But this cut will not make a major contribution to the Treasury’s bottom line and savings could create new costs. A smaller civil service could become even more reliant on expensive consultants – a problem highlighted during the pandemic and prioritised by Cabinet Office minister Lord Agnew.[4] Departments will also need staff to work on the day-to-day delivery of the government’s major projects portfolio, which increased from 125 projects costing £448bn to 184 projects costing £542bn in the last year.[5] Employing too few civil servants to manage these projects would cause problems and extra costs.

Ministers should also beware of the costly boom-and-bust cycle of civil service staffing. In 2016 DHSC planned for cuts of around one third by 2020. Redundancy rounds and voluntary exits took the department to a low of roughly 1,300 civil servants in 2017, making the resource gap in response to Covid even more acute. Defra fell from 2,600 officials in 2010 to 1,600 in 2016. But in responding to Brexit the department has replaced this lost resource and continued to grow, now reaching more than 5,500 officials.

Ministers should identify the workforce the government needs before making decisions

The chancellor’s target does not need to be met until 2024-25, which means ministers have time to avoid cuts that will undermine the government’s plans or cost more money than they save. They should collect better data about the skills, knowledge and experience of civil servants. That should inform a comprehensive workforce strategy as a successor to the expired 2016-2020 Workforce Plan, which the IfG has previously called for. This would identify the skills needed in the future, the prevalence of those skills in the existing workforce, and the skills that will be less necessary.

A strategy rooted in data would help ministers identify where skills and resource should be prioritised in departments. For example, the government wants more data, science, commercial and project delivery skills. Since 2016 the commercial profession has grown by 5%, science and engineering by 18%, digital, data and technology by 19%, and project delivery by 48%, but the policy profession has grown by around 71%. Ministers might identify departments where policy teams can afford to be reduced in order to free up resource in other areas. This would also fit with the government’s aim of using cuts to free up resource for frontline roles.

Civil service headcount should be based on what the government needs, not an arbitrary target. Given the chancellor has now set a target, the government should commit to developing a proper strategy to identify where those cuts should fall. Without that, the chancellor may find that his short-term fix will, inevitably, itself need fixing.

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1028813/Budget_AB2021_Print.pdf

- https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/thousands-civil-service-jobs-at-risk-spending-overhaul-7g6nv7785

- https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/81/health-and-social-care-committee/news/157991/coronavirus-lessons-learned-to-date-report-published/

- https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/sep/29/whitehall-infantilised-by-reliance-on-consultants-minister-claims

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/infrastructure-and-projects-authority-annual-report-2021

- Supporting document

- whitehall-monitor-2021.pdf (PDF, 5.68 MB)

- Topic

- Civil service Brexit Coronavirus

- Keywords

- Civil servants Civil service reform

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Publisher

- Institute for Government