Clear objectives will help make relocating civil servants a success

There are good reasons to move the civil service out of London, but the ‘why’ deserves as much attention as the ‘where’

The government has used the budget to announce civil service moves out of London. There are good reasons to do this, but the ‘why’ deserves as much attention as the ‘where’, says Sarah Nickson

The chancellor has announced that 22,000 civil servants will be shifted out of central London over the next 10 years. Among their number will be 750 staff from the Treasury and other departments who will move to an ‘economic campus’ in the north of England.

This government is not the first to attempt to decentralise the civil service. But relocations have not always achieved their goals, like improving economic growth outside the capital or overcoming perceived Whitehall groupthink. The new moves are part of the Johnson government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda – but this should not be the sole motive for its decision to increase the number of civil servants outside the capital.

Having clear objectives on what government can better achieve with a more diverse and nationwide civil service should guide ministers’ decisions, not soundbites.

Policy advisers are concentrated in London, but government is working to change this

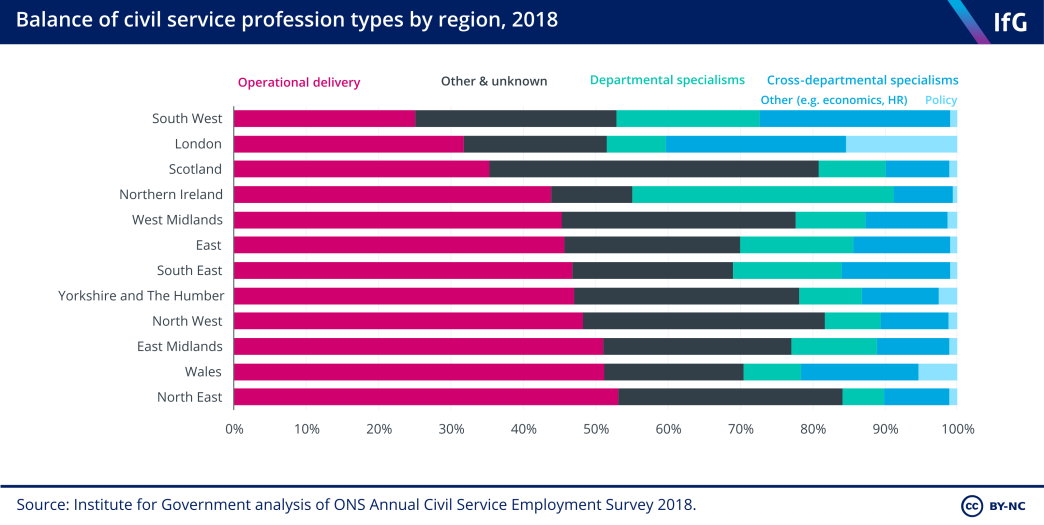

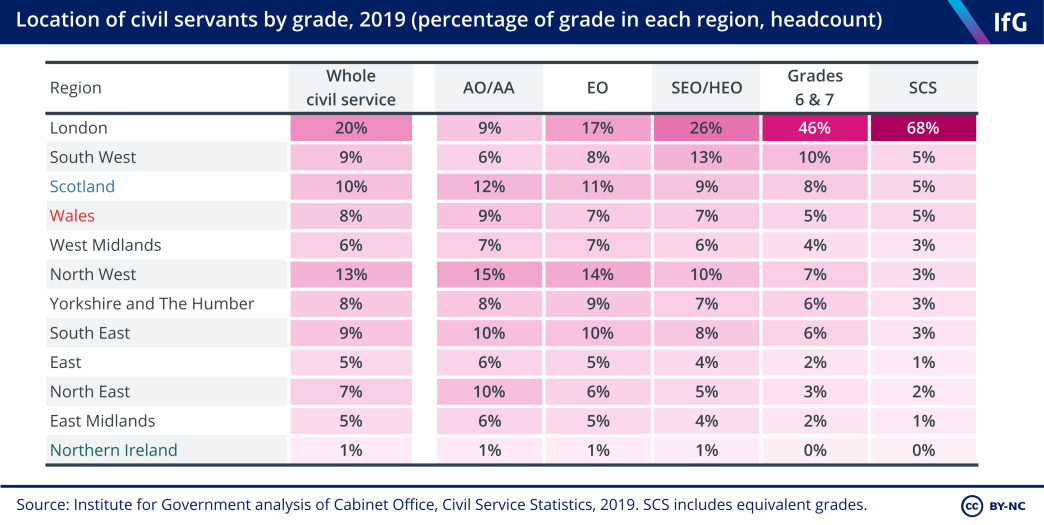

While only one in five civil servants is located in London, those advising ministers on policy are concentrated in the capital. London is home to around two thirds of policy professionals and senior civil servants.

More than 87% of staff from the Treasury, the Cabinet Office, DfT, DCMS, and BEIS were based in London in 2019. Other departments have a greater regional presence, particularly those with big delivery arms. For instance, the Department for Work and Pensions, the Ministry of Defence and Department for Education all have more than 50% of their staff outside London.

Before ‘levelling up’ entered the public lexicon following Johnson’s election victory, government was already looking into moving civil servants around the country. The Government Estate Strategy and the Places for Growth programme, both initiated in previous administrations, already support departments to relocate roles. Civil service ‘hubs’ outside London, including specialist clusters for health, transport and cultural policy, are being developed.

Ministers should look beyond numbers when deciding on moves

Historically, the motives for decentralising the civil service have fallen into three categories: cut costs, improve decision making and stimulate economic growth. The current government seems to be setting its sights on all three. But sometimes these aims can conflict. Being clear about its rationale will help government make good decisions about who should move, and where, and help avoid past mistakes.

The Government Estate Strategy emphasises the potential savings from basing civil servants outside London, and suggests targeting ‘areas with lower wage costs [and] cheaper property’. But cost alone should not dictate moves. There can be good reasons to move departments or agencies – from ensuring the civil service is able to draw on the country’s best talent to broadening the range of policy perspectives in government – even if costs rise.

When planning its move to Salford, the BBC anticipated the net cost of its estate would rise by up to £120m over the period to 2030, but went ahead with the aim to improve its content and better serve audiences in the north of England. Nine years on, the corporation sees the decision as having met these aims.

The budget claims to set out ‘how the government will make decisions differently in future’. If it is serious about this, the 22,000 officials must include substantial numbers of policy advisers and senior staff – something that has been resisted in previous decentralisation attempts.

At the same time, ministers must also be mindful of where policy experts and specialists are located. When the Office of National Statistics (ONS) shifted operations to Newport, 90% of its London-based staff stayed behind, in many cases because of a lack of job options for employees’ partners. The ONS struggled to replace former staff and a review nine years later found the relocation contributed to loss of analytical capability and deterioration in performance.

Civil service moves alone will not ‘level up’ the country

The ONS example shows the potential trade-off between spreading economic prosperity – the driver of the Places for Growth programme – and achieving better policy outcomes. And government should also not assume any regional economic benefits it does achieve from its relocation programme will be substantial. The BBC’s Salford move only led to a marginal increase in jobs in greater Manchester (beyond those moved by the BBC itself).

There are good reasons to re-think civil service locations: moves could save government money and improve policy. But ministers should be realistic about the cost savings, and clear about the government’s objectives, if these moves are to be a success.

- Topic

- Civil service

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government