The case for a Brexit state aid compromise

Alex Stojanovic sets out a route to a compromise on state aid

Alex Stojanovic sets out a route to a compromise on state aid which could be advantageous to the UK and unlock the Brexit stalemate

Are the two major Brexit sticking points any closer to becoming unstuck? There have been hints from both sides at movement over fishing rights, but the EU and the UK positions on state aid had appeared far apart: the EU wants agreement on rules to curb subsidy use but the UK is determined to resist any commitments that might tie its hands. However, the Financial Times is now reporting that a landing zone has been identified. The details have yet to emerge, but a recent IfG paper, Beyond State Aid: The future of subsidy control in the UK, argues that the UK has much more to gain from a compromise on state aid than the EU – and would be wise to have its own system of subsidy control after the transition period ends, regardless of any agreement with the EU.

A subsidy race would harm the UK more than it would the EU

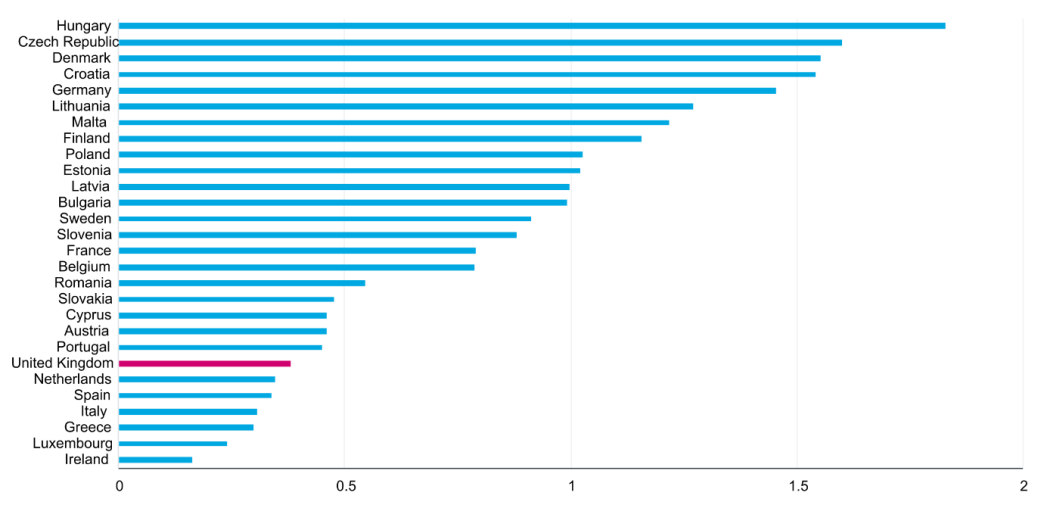

The UK has not made much use of subsidies in the past in comparison to other member states, spending just 0.4% of GDP on state aid in 2018. This compares to an average of 0.8% across the EU as a whole, with 10 member states including Germany having spent over 1% of GDP on subsidies.

The government wants the freedom to use subsidies more actively. However, encouraging a subsidy race with the what will still be its largest trading partner would be bad for both sides, and, given the larger size of the EU, especially bad for the UK. The EU has not been afraid in the past to use subsidies to prise investment away from rivals (including countries with which it has signed free trade agreements).

In the event of no deal, the only mechanism the UK would have for addressing harmful subsidies from the EU would be the WTO Anti-subsidy and Countervailing Measures Agreement. This is not sufficient protection given the stymied state of the WTO’s mechanism for resolving disputes.

Instead, the UK and the EU could negotiate a bespoke process to resolve disputes on subsidies where they might have harmed trade or competition. Given the size of the EU and inclination of member states to use subsidies, the UK could be more likely to make use of this than the EU.

A compromise on state aid would not significantly restrict the UK's freedom

A deal would require both sides to maintain an independent regulator to monitor the use of subsidies, and it would allow both sides to raise disputes. The former is in the UK’s interest regardless of a deal, as it would allow it to retain its autonomy while providing a credible check on waste and cronyism. On the latter, the UK could ensure that only the significant subsidies get disputed by requiring the accuser to demonstrate evidence for how a subsidy has harmed trade. That would mean most subsidies would be unlikely to qualify.

This arrangement would allow the government to offer most subsidies it believes will help achieve its policy goals, such as subsidising tech, net zero or ‘levelling up’. And by committing to some shared principles and rules, rather than EU rules, the UK would have greater flexibility to diverge over time as the country develops its own distinctive case law.

A deal offers the best chance of a long-term resolution to the state aid provisions of the NI protocol

The UK Internal Market Bill, now making its way through parliament, has raised the stakes. Article 10 of the NI protocol gives the EU Commission jurisdiction over subsidies that affect trade in goods between NI and the EU. This potentially catches many UK-wide subsidies – as any UK business with operations in NI would likely need Commission approval on any subsidies received. In response, the UK Internal Market Bill has given ministers the power to breach this aspect of the protocol.

A compromise on state aid could make it possible to override the application of Article 10 without breaking international law. The expansive provisions of the protocol on state aid are not just a problem for the UK, they create practical problems for the EU to apply and to enforce as we argued in our recent paper. If the UK can show that it has a strong domestic subsidy control regime, alongside a workable dispute resolution mechanism for contentious subsidies, the EU may allow for Article 10 to be superseded by the UK regime, solving a major headache for the UK and EU over the future application of subsidy control in Northern Ireland.

There is no good reason to allow the issue of state aid to lead to no deal. If reports are correct, the UK could gain an advantage from a compromise, even if the current government appears not recognise that this a possibility.

- Supporting document

- beyond-state-aid.pdf (PDF, 705.59 KB)

- Topic

- Brexit

- Keywords

- Subsidy control Northern Ireland protocol

- Publisher

- Institute for Government