Carillion collapse shows weakness of public vs private finance debate

Government must build the evidence to understand when private finance provides better value for money than public spending.

The debate over whether private finance is better value than public spending is heating up after Carillion’s collapse – but it is hampered by a lack of evidence on either side, says Graham Atkins.

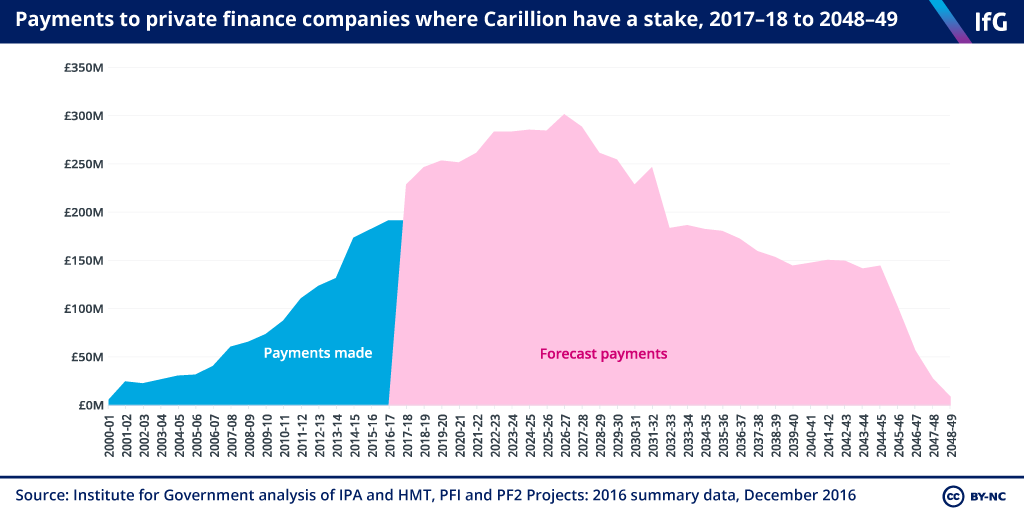

Successive governments have used private finance to deliver social and economic infrastructure – from schools and hospitals to roads and railway maintenance. The public sector has paid £1.4 billion to private finance companies where Carillion has a stake, and future payments to these companies are predicted to cost £6.3 billion.

Carillion’s failure has sparked renewed interest in the issue of private finance contracts. Government and opposition leaders say that the organisation’s collapse is evidence of the success and failure of private finance respectively.

But – critically – we don’t know how much these infrastructure projects would have costed if they had been financed through public spending. This is essential to determine whether these contracts are good value for money.

The real problem in the private finance debate, as we argued in our report Public vs Private, is that the evidence on the value of using private finance instead of public spending to deliver public infrastructure is thin. And where evidence does exist, it is mixed.

Sometimes, private finance companies appear to have improved management. A 2002 Treasury review of public and private finance found that, in general, cost and time overruns are less frequent and less extensive in private finance projects. But in other cases governments have paid a premium to transfer risks to the private sector, and then paid again when companies cannot manage those risks and are bailed out – as happened with High Speed One and Metronet. The overall picture is not clear and too often evidenced is anecdotal.

Some of Carillion’s losses may represent successful risk transfer

As well as making better financing decisions, the Government faces the more pressing question of how to deal with Carillion’s existing private finance contracts.

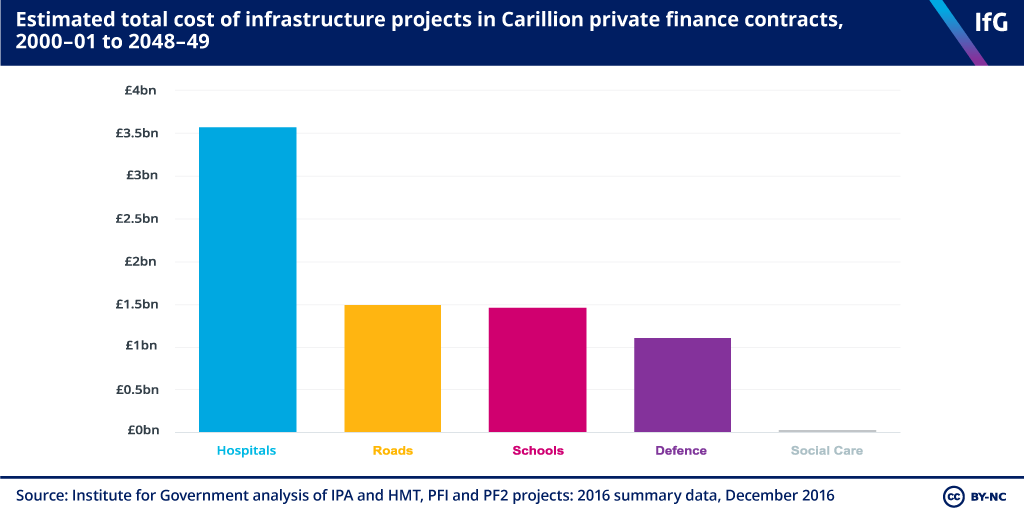

Carillion owned stakes in 17 private finance contracts, primarily in hospitals, schools and roads. This included a third of the new private finance contracts, known as PF2.

Reporters at the BBC and The Guardian argue that Carillion’s involvement in private finance projects was the immediate cause of its ailing financial position. Cost and time overruns at the Midland Metropolitan and Royal Liverpool hospitals and the Aberdeen Western bypass led to financial losses for the construction and services company.

But – perversely – the losses that Carillion and other investors absorbed in these projects may represent part of the value of private finance contracts to the taxpayer.

One argument for private finance is ‘risk transfer’ – that the private sector is better placed to manage the risks of projects running over time and over budget than the public sector. Most private finance contracts bundle construction and operation costs so that construction firms and investors do not make a profit until projects are operational. This means private money invested is ‘at risk’ until projects are completed, which should incentivise the private sector to deliver efficiently.

Even if the private sector does not deliver more efficiently, if it incurs losses but projects are still delivered then that may represent successful risk transfer by government. But if the private sector parties go bust and the taxpayer picks up additional bills to keep projects running, then risks haven’t really been transferred at all.

Carillion’s failure has left the Government with a difficult choice

Carillion’s failure has left the Government with an unenviable decision. If it didn’t step in, then critical infrastructure projects would not have gone ahead. If it bailed out Carillion, it risked undermining outsourcing by sending a signal to firms bidding for contracts that they need not bid realistically or manage projects well, as the Government wouldn’t allow them to fail.

The Government chose not to bail out Carillion to avoid this moral hazard problem, but there are still lessons from Carillion’s failure.

Government must build the evidence to understand when private finance provides better value for money than public spending. And it needs to be more realistic about whether investors and construction firms can absorb losses when things go wrong. If they cannot, then government should consider different contracting options.

- Supporting document

- Institute_for_Government_Infrastructure_Finance_Option_Public_Private_November_2017_Web_Final.pdf (PDF, 485.56 KB)

- Keywords

- Outsourcing

- Publisher

- Institute for Government