David Cameron has publicly stated he will not serve a third term, so regardless of the European Union (EU) referendum outcome, we can expect a change of Prime Minister before the end of Parliament. Catherine Haddon examines how changes of PM have occurred previously and how our constitution enables this to happen.

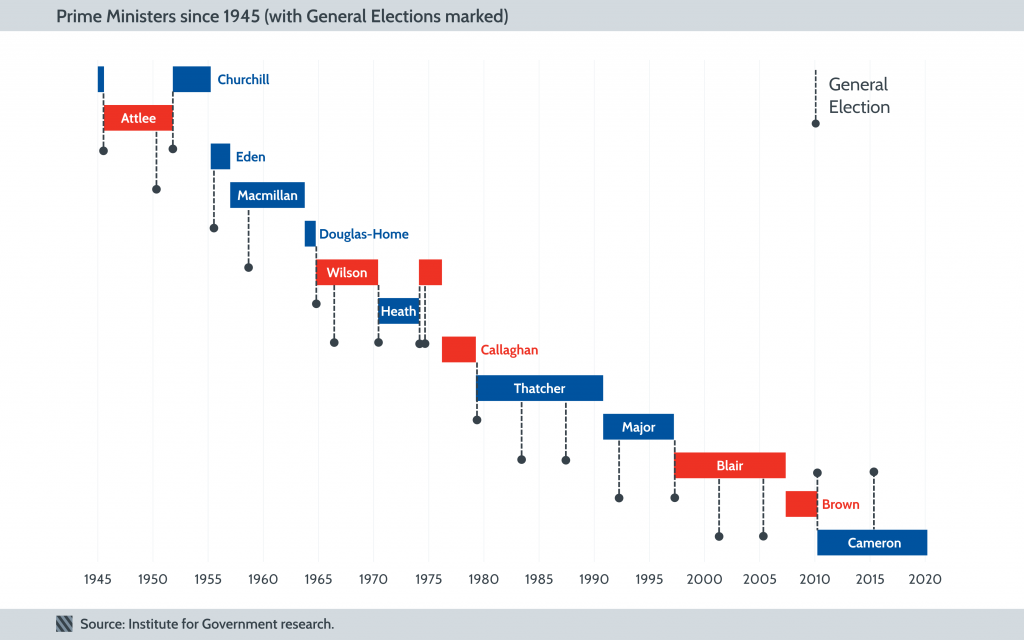

It is far from unusual for us to have a change of Prime Minister without a general election. Since the Second World War there have been almost as many changes of PM from within the same party as there have as a result of a general election (six during a parliament, seven as a result of an election).

The key is whether a new PM can continue to carry the confidence of Parliament – i.e. whether their party has a majority. David Cameron is not alone in announcing an early retirement within a parliament, but he has created lots of speculation about when and how he would go, something that has only been complicated by the EU referendum.

Both Harold Wilson in 1976 and Tony Blair in 2007 announced their retirement before the end of Parliament. For Blair it was a long-expected departure, while for Wilson it was more of a surprise. However, in both cases they gave only a few weeks’ formal notice of their resignation.

In 1976 Wilson announced his impending resignation on 16 March, and endorsed James Callaghan as his successor. Callaghan won the subsequent leadership election and took office on 5 April. It was a swift process because it only involved Labour MPs voting for the new leader.

In May 2007 Blair announced he would be standing down as PM on 27 June. This formally triggered a leadership contest in the Labour party, but it was widely expected that Gordon Brown would succeed him. The only other candidate to put their name forward, John McDonnell, failed to get enough support to get onto the ballot, so Brown was elected unopposed.

One certainty is that, as with Blair and Wilson, Cameron would remain as PM while any new leadership contest occurred. In our constitution, we cannot be left without a PM. If Cameron were to resign from post then the Queen would have to call immediately for a successor, but it has to be clear who this would be. This is why Gordon Brown remained in office for five days after the general election in May 2010 while negotiations took place among the parties to form a coalition government. Brown resigned only when it became clear that Cameron was going to be the next PM, though before a coalition deal was finalised with the Lib Dems.

But now with a Conservative majority in Parliament, any successor would be expected to come from that party. This means that a Conservative Party leadership contest has to be followed, and that could take some time.

There have been times in our history when an outgoing PM was able to simply advise the Queen on whom to call as a successor. In 1963 this, albeit informal, advice was considered controversial in affecting a leadership battle within the Conservative Party to replace Harold Macmillan.

In 1990, after she failed to secure a majority in the first round of a leadership contest, Margaret Thatcher announced her resignation on 22 November and others put their names forward. John Major failed to win an outright majority in the second round of voting on 27 November, but the other candidates withdrew. He was therefore elected unopposed and became PM the following day.

In 1998 the Conservative Party rules were changed again to allow both MPs and party members to vote in a leadership election. In contrast to the Labour Party version of one member, one vote, the Conservative process sees successive ballots of MPs to whittle down candidates to two names. Only these two candidates are then put to the entire Conservative Party membership, around 150,000 people as of 2014.

This process of balloting members takes time. The only way it could be swifter is if only one candidate’s name is put forward, who is then elected unopposed, as happened with Michael Howard in 2003. However, this seems unlikely this time around. The last leadership contest, in 2005, when Cameron was elected, took about six weeks for this second part to be completed.

The timing of Cameron’s departure may be down to him, it may not. His decision to announce he would not fight for a third term has added another dimension of uncertainty about a future change of PM, regardless of the EU referendum result. But one fixed certainty is that, however such a resignation occurs, he has duty to remain in office until it is clear who will succeed him. In this and in much else, he has plenty of predecessors to provide useful examples.