Devolved elections 2016: politics and parliaments

Ahead of elections in the UK’s devolved nations on 5 May, Leah Owen examines the results of the previous elections in Wales and Scotland (but not Northern Ireland, where the system is different).

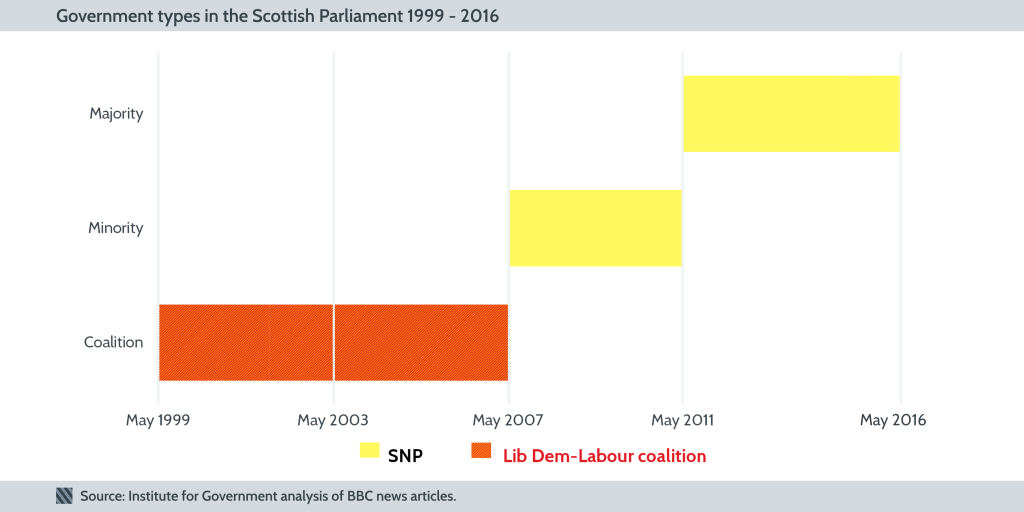

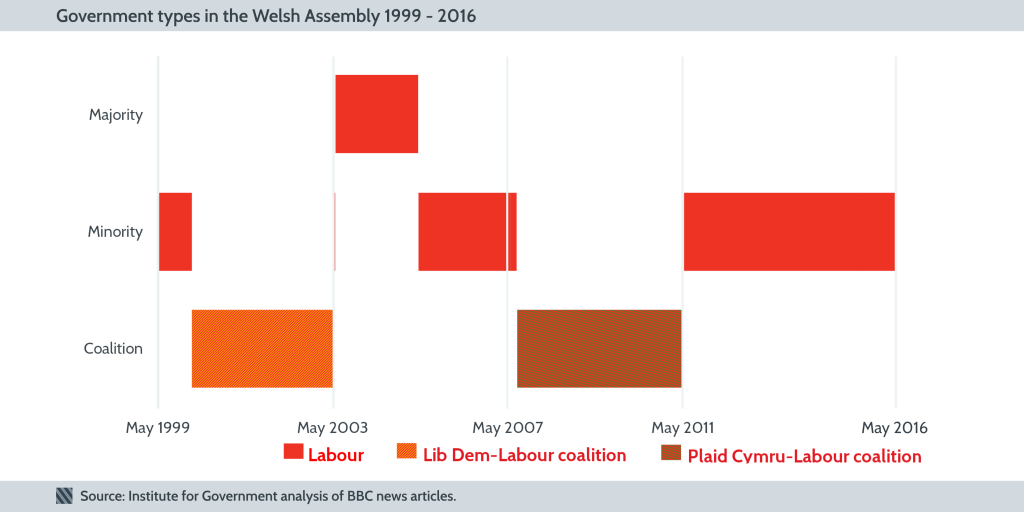

Coalition and minority rule – not majority government – are the general rule in Scotland and Wales.

Since 1918, most governments in Westminster have been majority ones (although nearly 30 years have been spent under minority or coalition government). In Scotland and Wales however, the electoral system is designed to make majority governments rare.

In Scotland, Labour and the Liberal Democrats formed coalition governments in 1999 and 2003, but seat losses in 2007 meant that Labour and the Liberal Democrats no longer represented a majority, and the SNP had become the largest party. Instead, the Scottish National Party formed a minority government in 2007, and a majority one in 2011.

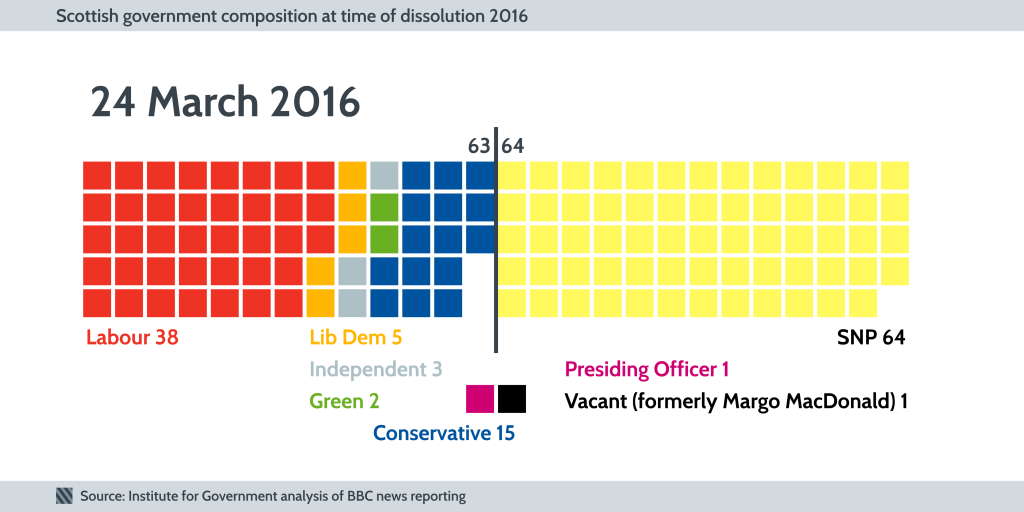

The SNP’s 2011 majority (initially 69, or five seats) has reduced over time; defections and resignations mean that since 2014 they have had only 64 MSPs – only a majority due to a vacant seat following Margo MacDonald’s death in April of that year.

In Wales, Labour has always been the largest party but has only had a majority government after the 2003 election, when Lord Elis Thomas – an AM for Plaid Cymru – was elected Presiding Officer, giving Labour a narrow majority of 30 of the 59 voting seats. They also received 30 seats following the 2011 elections, choosing to govern alone then as well.

Alun Michael headed a minority administration after the 1999 election, but Labour entered coalition with the Liberal Democrats in 2000 after he was replaced by Rhodri Morgan. Labour also went into coalition with Plaid Cymru after the 2007 election, following a short period of minority rule.

Scottish Labour support has decreased at each election, from 56 seats in 1999 (making them the largest party) to 37 in 2011.

The SNP, by contrast, have reversed a slight decline in 2003, to winning more seats than any other party (though not a majority) in 2007, and an outright majority in 2011 – 69 of 129 seats, though, as mentioned above, this lead had eroded by March 2016. The Scottish Liberal Democrats have gone from 16 seats in 2007 to five in 2011.

While Welsh Labour remains strong, the ‘second party’ has shifted over time – from Plaid Cymru to the Conservatives.

Labour has always been the largest party in the Welsh Assembly. Until the 2011 election, second place was held by Plaid Cymru, but the number of seats they hold has declined over time, so they now hold only 11.

The Conservatives, by contrast, have slowly increased the number of seats they hold at each election, up to 14 in 2011 – making them the second largest party in the Welsh Parliament. Wales hasn’t seen a proliferation of small parties or independents, but polling suggests UKIP could win regional Assembly seats for the first time.

The Additional Member System produces its own distinct set of results in Wales and Scotland, compared to UK General Elections.

Unlike UK general elections, which operate solely on a ‘first past the post’ (FPTP) basis, the devolved assemblies have an ‘Additional Member System’ (AMS), which elects candidates based on a mix between FPTP and proportional representation.

AMS comprises two votes: one for a constituency member, and one for a regional party list. The second vote is used to ensure greater proportionality by compensating those parties that win few individual constituencies but a larger share of the vote. You can read more about the system here.

During our post-General Election liveblog last May, many people noted how FPTP affected different party’s seat share versus vote share, with winners ‘winning big’, at smaller parties’ expense. The 1997 Labour landslide was based on a 43.2% vote share, for example. T

he Additional Member System means parties’ share of the seats becomes much closer to their share of the vote in both Scotland:

and in Wales:

As can be seen, the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly both have a system that makes majority victories less likely – but not impossible, as close majorities by both Welsh Labour and the SNP show. Under AMS, top parties generally still gain more seats than their vote share would suggest, and ‘others’ are seldom well-represented (largely because lots of votes for small parties are wasted).

On the whole, however, AMS ‘flattens’ the votes versus seats disparity, making majority government rarer – and coalitions and minority governments more common – in Scotland and Wales than in Westminster. The Welsh and Scottish electoral systems lead to a greater likelihood of coalition or minority government, though this is not always certain.

We will have to wait until 6 May – or later, if no majority is reached and parties enter coalition negotiations – to see what happens. One thing we do know, however, is that coalition and minority government bring their own challenges – luckily the Institute has looked at the practicalities of non-majority and coalition government before, in Ireland and internationally.

- Topic

- Devolution Ministers