Earlier this month, Environment Secretary Liz Truss told an audience at the Institute for Government about her plans to reform and modernise the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Gavin Freeguard and Oliver Ilott look at two of her key themes – working with arm’s-length bodies and #opendefra – in charts.

Liz Truss wants Defra’s arm’s-length bodies to work together…

One key theme of Liz Truss’s speech on modernising Defra was getting its various arm’s-length bodies (ALBs) and the main department to work in alignment. The Secretary of State would like the various organisations in the Defra departmental group to make plans around shared policies, rather than working in discrete fiefdoms, and to reflect this joint working through the adoption of shared operational functions.

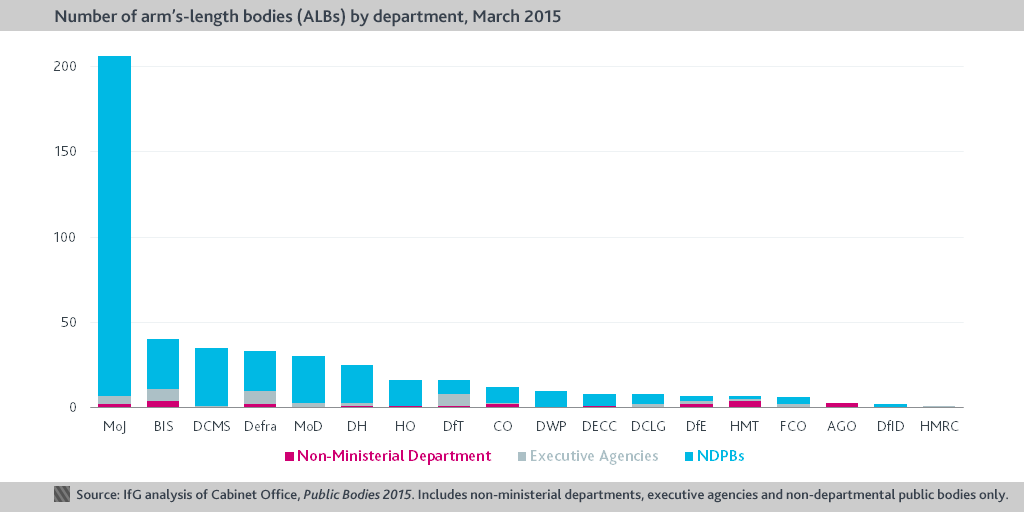

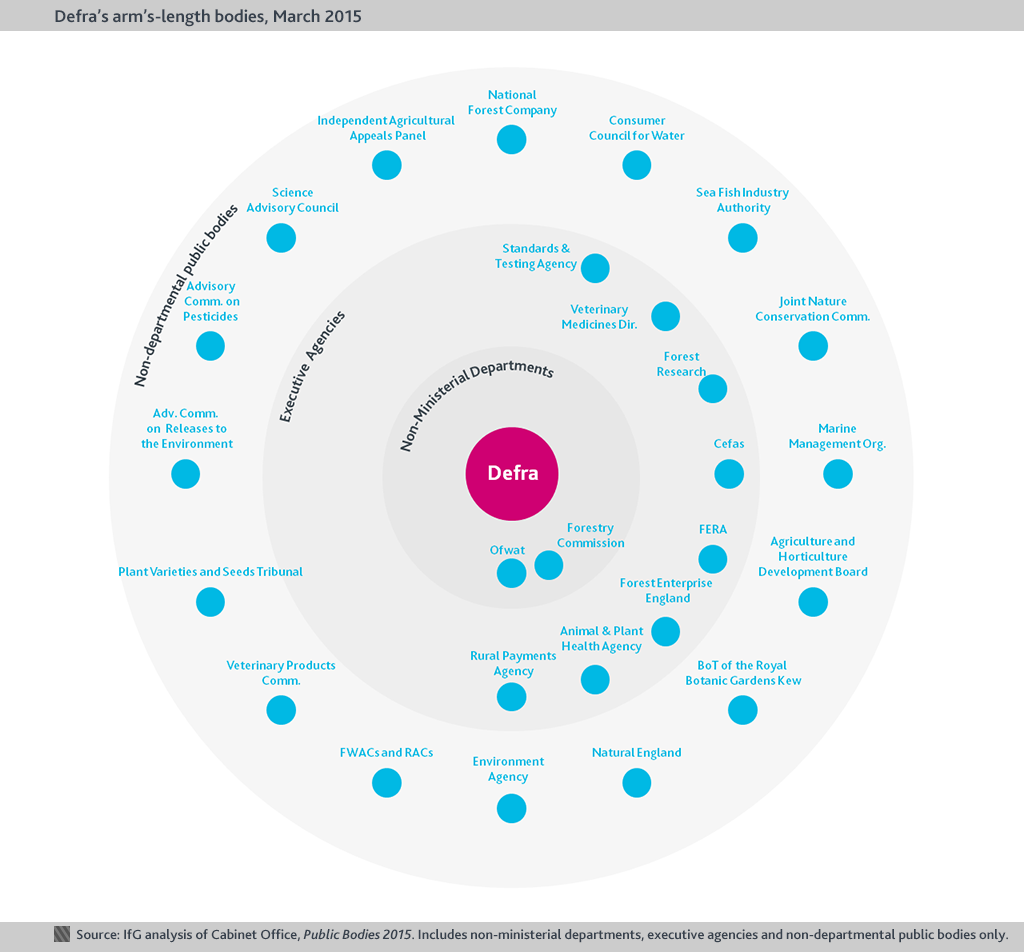

Compared to other departments, Defra has the fourth largest number of ALBs according to Public Bodies 2015. A considerable number of these have been abolished since 2010, as we saw in Whitehall Monitor 2015. To achieve her goal, Liz Truss will have to coordinate the department’s 34 arm’s length bodies, as depicted in the ‘orbit’ chart below (we have listed 26 entities, having combined the nine small Regional Advisory Committees and Forestry and Woodlands Advisory Committees).

These bodies are categorised by the Cabinet Office into two non-ministerial departments, eight executive agencies and 24 non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs). Not shown are Defra’s 13 other public bodies listed by GOV.UK (including the national park authorities) or the 16 government companies identified in a recent National Audit Office report.

Each category is intended to reflect varying degrees of control by the department, although the Institute for Government has previously argued that the Cabinet Office categorisation should be clarified. In 2010, we proposed simpler taxonomy for ALBs whereby organisational form relates clearly to the function an ALB performs. While this proposed taxonomy has been endorsed by the Public Administration Select Committee, it has not been adopted by Government, and so we continue to use the Cabinet Office’s imperfect categorisation.

Indeed, the Cabinet Office has itself issued conflicting guidance: while in our orbit charts we follow the categorisation from Public Bodies 2012 (published January 2013), a guide for departments (published December 2012) gives a slightly different order, bringing executive agencies closer to the minister and pushing non-ministerial departments further away. This underlines the need for greater clarity and consistency.

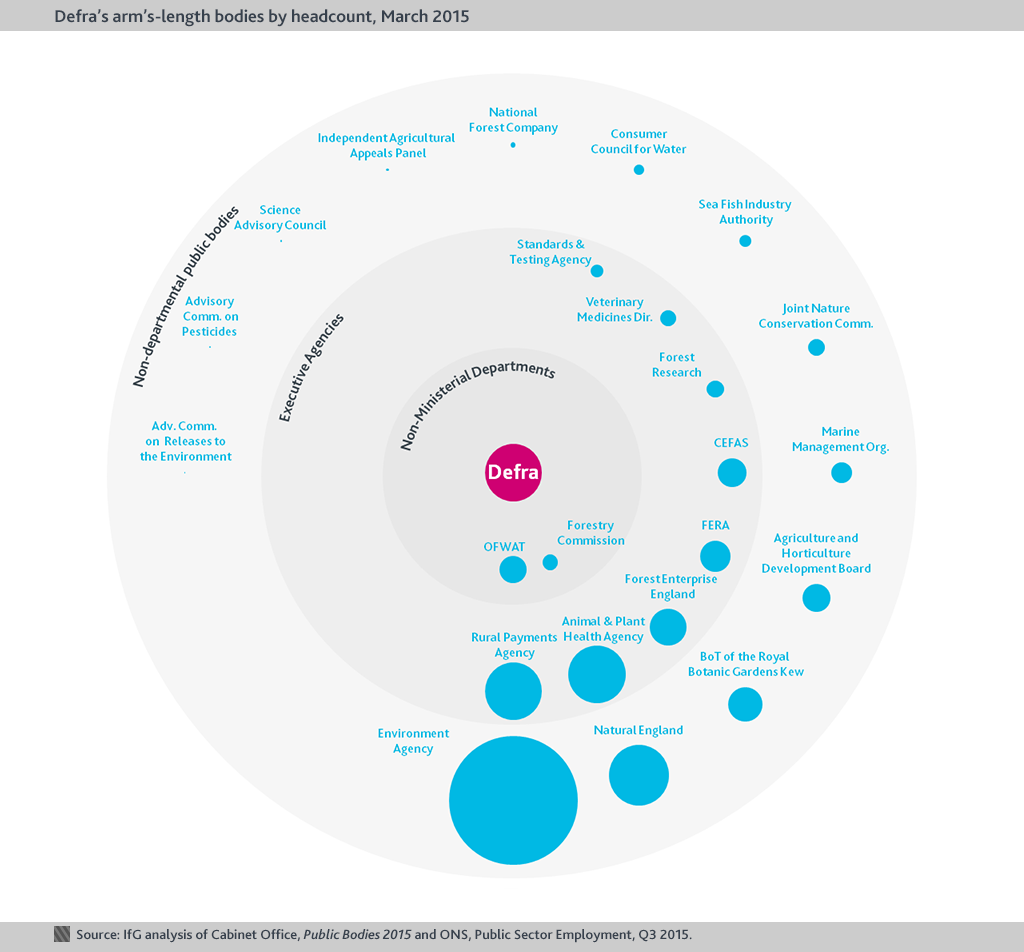

… but some of them are bigger and better resourced than the department itself

The challenge of coordinating these bodies will be accentuated by the fact that they are far from uniform in their size and import. Measured by headcount on this orbit chart, Defra is actually smaller than some of its ALBs. It may prove difficult for a small centre to manage the operational activity of a large body established by statute such as the Environment Agency. Similar efforts to share services across Whitehall have not gone well.

Many of Defra’s bodies gain additional independence from the fact that they do not rely on Government funding. A comparison of the orbit chart for ‘Total Expenditure’ and ‘Government Funding’ reveals that organisations such as the Agriculture, Horticulture and Development Board fund all their expenditure from non-government sources.

Open data and using data are also key parts of modernising Defra.

Another key theme of Liz Truss’ speech was a commitment to pursue #opendefra, a strategy which includes opening up 8,000 datasets by Summer 2016 and improving the way it uses its own data, to become a data-driven department.

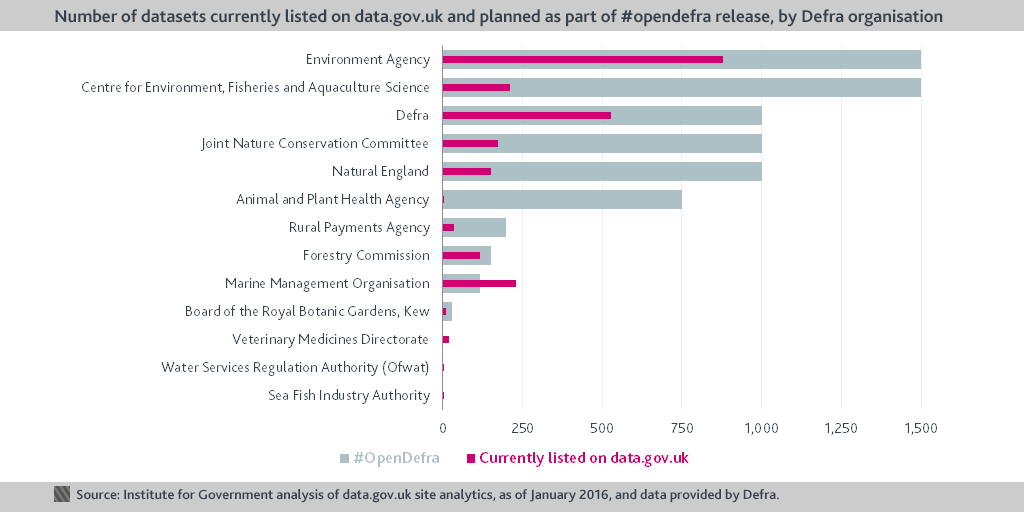

Defra estimates that as part of #opendefra, the Environment Agency and Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture will each be responsible for 1,500 of the 8,000 datasets, while Defra, the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and Natural England will be responsible for 1,000 each (the grey bars above).

All of these organisations already have a number of datasets – not all of them open – listed on data.gov.uk, the government’s searchable data website. The Animal and Plant Health Agency in particular will be opening up a lot of datasets not currently available.

Using the analytics on data.gov.uk, we can get some idea of how people are using Defra data. The data from here can only be indicative: lots of government data is published elsewhere (for example, on GOV.UK), not all of the datasets listed are open (implying some issues around what counts as a ‘dataset’) and we have encountered a few inconsistencies. This underlines the need for better data on how the public is actually using data.

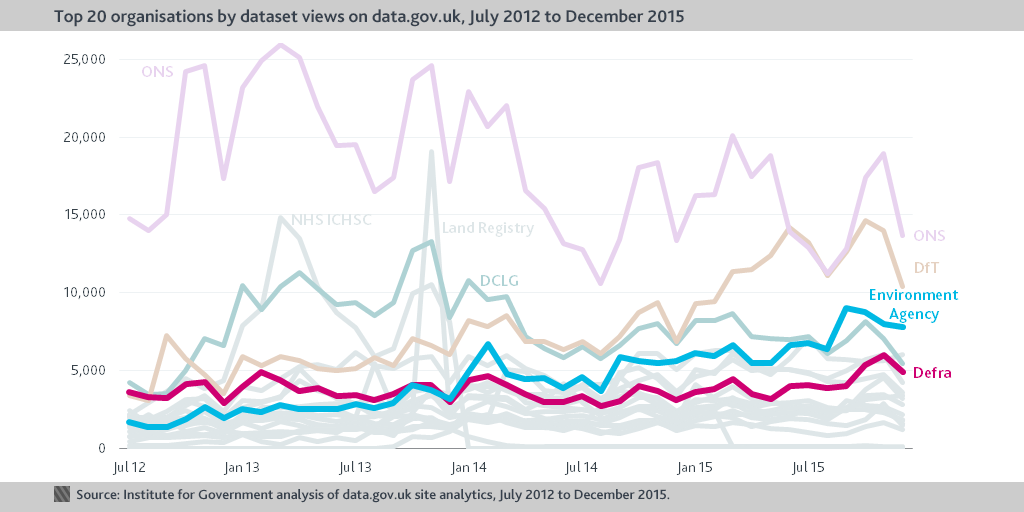

Both the Environment Agency and Defra are in the top ten most viewed organisations on data.gov.uk.

As of January 2016, the Environment Agency and Defra itself were two of only seven government organisations with more than 150,000 views of their datasets on data.gov.uk. In December 2015, Environment Agency datasets had just under 8,000 views, Defra ones just under 5,000. The next most viewed Defra organisation was Natural England (under 20,000 over time, and just over 1,300 in December 2015).

The Open Data Institute has shown that at the Environment Agency, an increase in the number of data sets available and the decision to stop charging for non-commercial use of their data has “helped raise awareness about environmental issues and flood risks, helping EA to achieve its core, overarching objectives”.

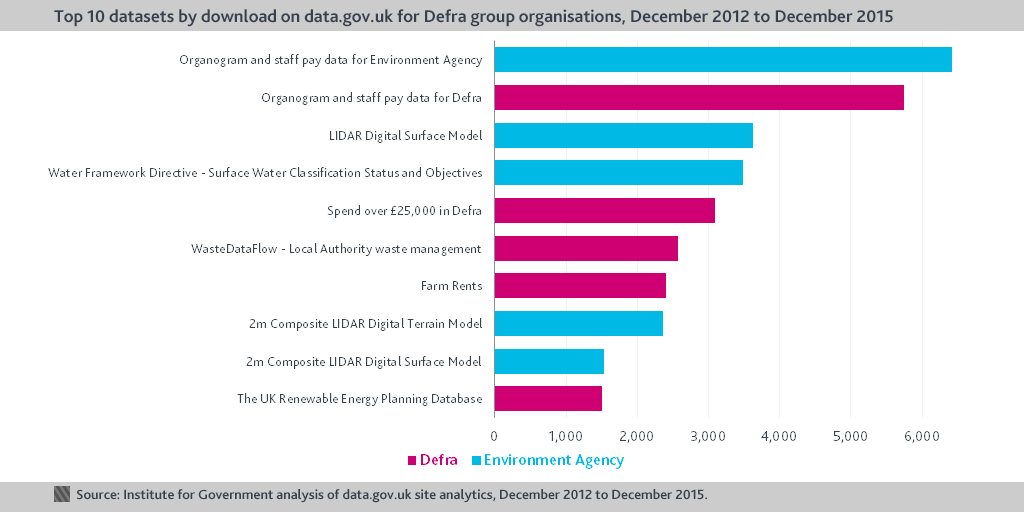

Since December 2012, organograms for Defra and the Environment Agency have been the most downloaded datasets across Defra.

Three of the top ten most downloaded Defra datasets – organograms for both the department and the Environment Agency (which give details of staff positions and salaries), and Defra spend above £25,000 – relate to the administration or operation of the department and its organisations. Five of the top ten datasets are owned by the department, and five by the Environment Agency.

Between December 2012 and December 2015, the most downloaded Defra dataset – Environment Agency organogram data – was downloaded 6,422 times. It lies 30th in the download statistics across the whole of data.gov.uk: the top three are Road Safety Data (DfT, over 60,000), and English Indices of Deprivation (DCLG) and Bona Vacantia Unclaimed Estates and Adverts (Treasury Solicitor’s Department, now the Government Legal Department, both just over 30,000 downloads).

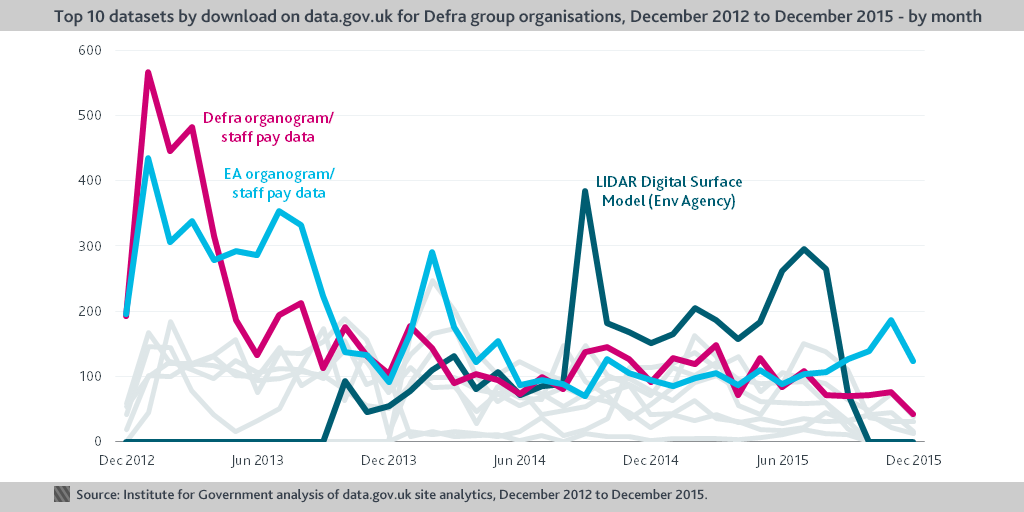

Although the organograms remain the Defra group’s most downloaded datasets, downloads have fallen since 2012 and 2013. In recent years, some more ‘practical’ datasets – notably the LIDAR 3D mapping data – have come to the fore.

Defra’s modernising agenda is ambitious. In aligning its ALBs around policies, the department is seeking to combine the best of in-house and arm’s-length – as Liz Truss noted in her speech at the Institute for Government, government has previously switched from one fashion to the other without combining the best of both. In releasing 8,000 open datasets, Defra would apparently be responsible for one third of all open datasets across UK government.

In seeking to better coordinate Defra’s ALBs and in its commitment to open data, Liz Truss has identified priorities that can make Defra a more effective department. The IfG will continue to monitor progress against these challenging objectives.

- Topic

- Public finances