Departmental budgets

Which government departments spend the most?

What are departmental budgets?

Departmental budgets refer to the money departments spend each year on things such as public services, welfare and infrastructure investments.

These budgets account for seven out of every eight pounds of public spending in the UK, with the remaining one-eighths covering areas such as debt interest payments or local authority spending financed through council tax.

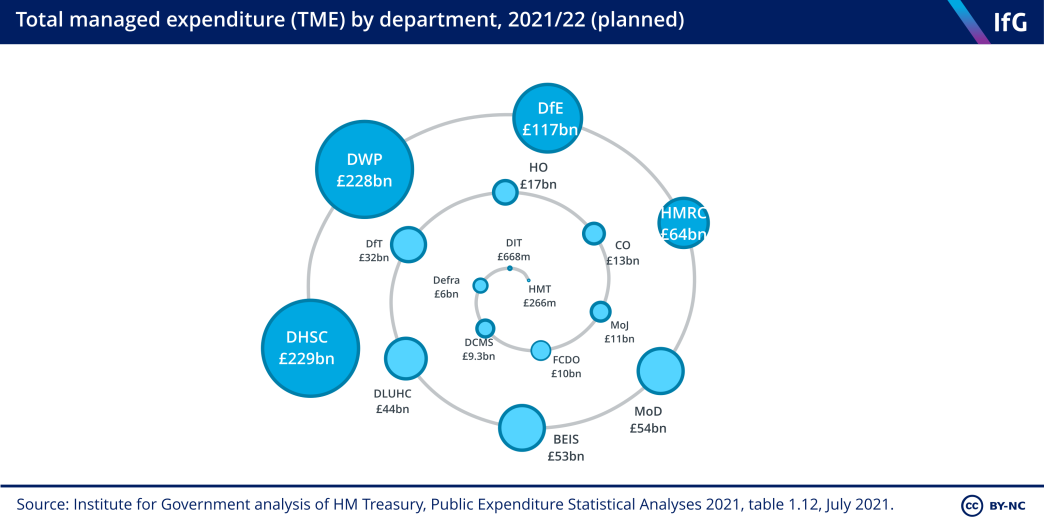

How much does each department spend?

The departments that planned to spend the most in 2021/22 are:

- the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), which is responsible for benefits and the state pension

- the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC), which is responsible for funding the NHS

- the Department for Education (DfE), which is responsible for providing schools grants.

- HM Treasury (HMT) and the Department for International Trade (DIT) spend the least

What is included within a department’s budget?

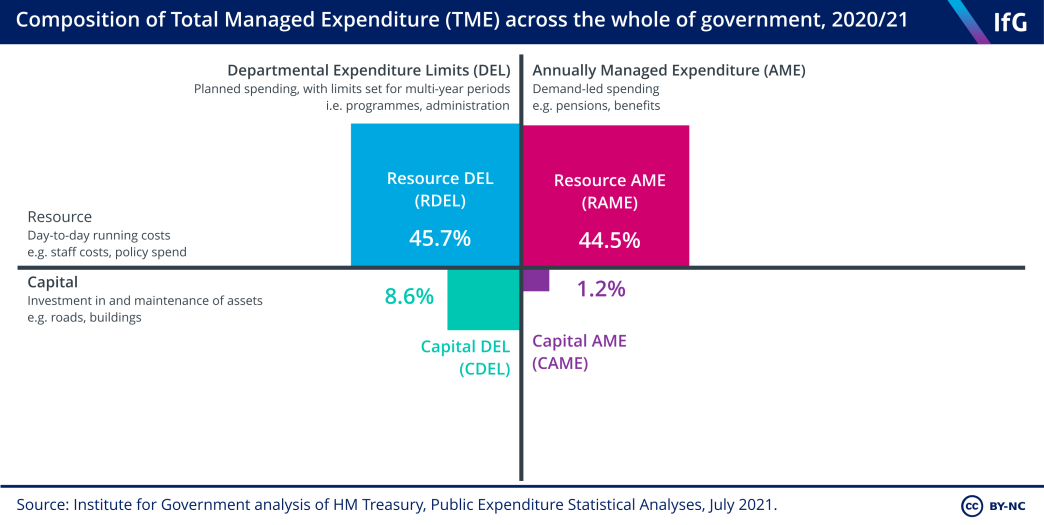

A department’s overall budget is referred to as its Total Managed Expenditure (TME), and this can be broken down into several components. 6 www.gov.uk/government/publications/how-to-understand-public-sector-spending/how-to-understand-public-sector-spending

Resource vs. Capital

- Resource spending relates to day-to-day operations, including administrative costs for departments, and programme spending which pays for things such as public services and state benefits.

- Capital budgets are spent on investments that add to the public sector’s fixed assets, including transport infrastructure (e.g. roads and rail) and public buildings.

Departmental Expenditure Limits vs. Annually Managed Expenditure

- Departmental Expenditure Limits (DEL) cover plans that departments are committed to, announced at spending reviews. They are often set for a multi-year period, and spending is limited, meaning departmental leaders cannot overshoot their allocated DEL budget.

- Annually Managed Expenditure (AME) is defined as spending that ‘cannot reasonably be subject to firm three-year limits’. AME is harder to predict and often relates to functions that are demand driven, such as pensions or welfare payments.

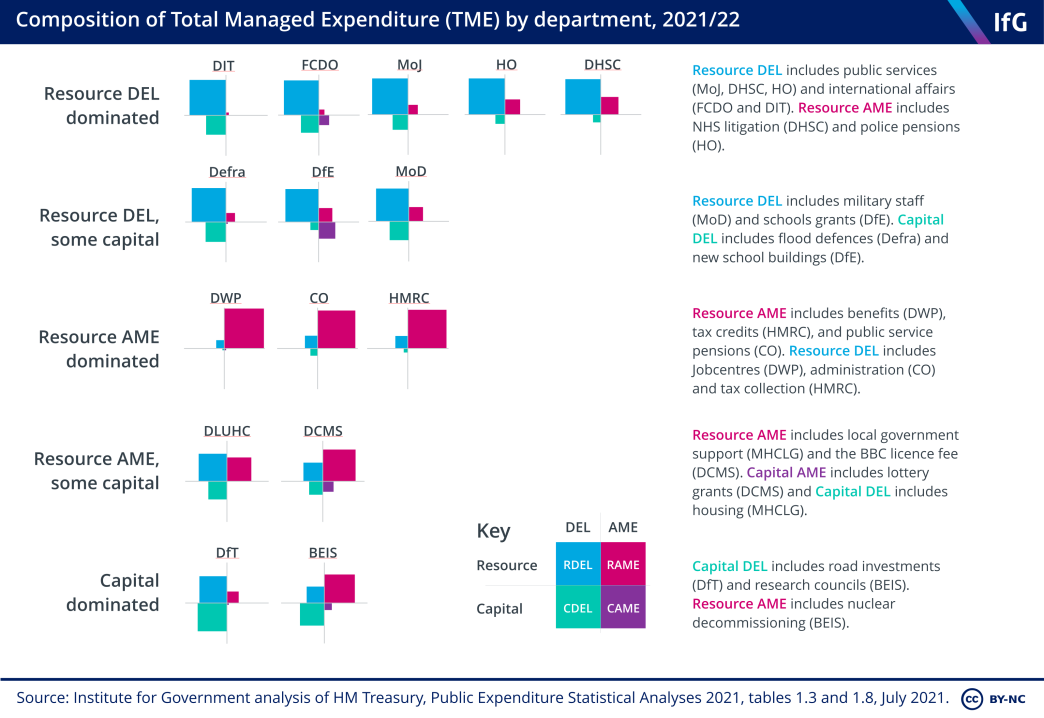

The composition of budgets varies by department, depending on their responsibilities.

While it is useful to understand how much departments spend overall, some elements of this spending are outside a department’s day-to-day control, such as demand-driven welfare spending at DWP. To understand how much departments spend on their controlled, day-to-day responsibilities, it is often more illuminating to concentrate on resource DEL budgets (which we will refer to as day-to-day spending).

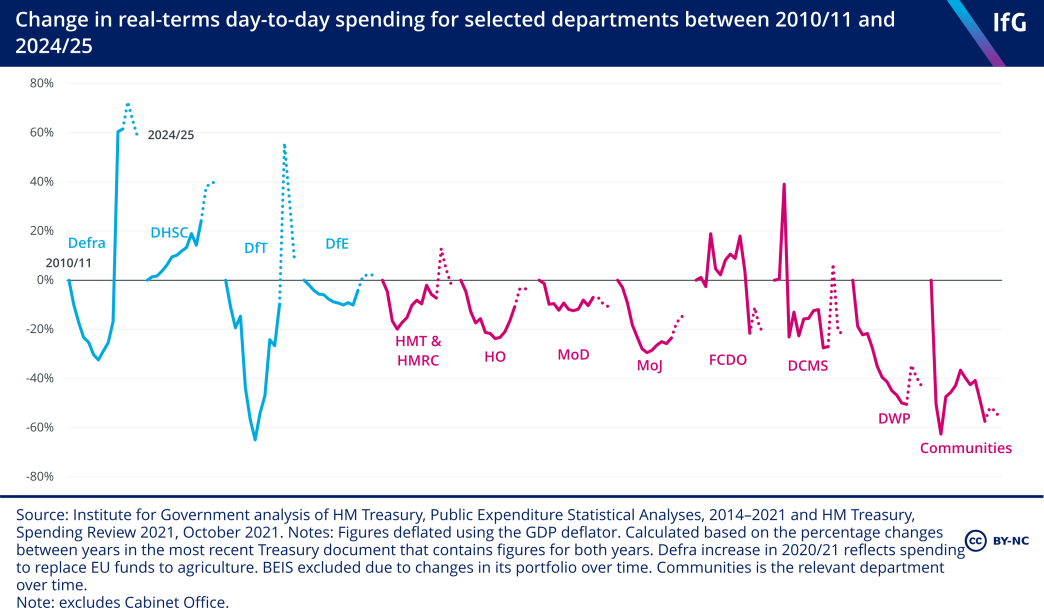

How has each department’s day-to-day spending changed?

Between 2010/11 and 2019/20, day-to-day spending in most departments (on a like-for-like basis) fell considerably. In 2020/21, in response to the coronavirus pandemic, some departments spent much more (including DHSC on the NHS and the department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy on grants for businesses).

Plans set out in the 2021 Spending Review imply that spending in all departments will increase between 2021/22 and 2024/25 (excluding temporary covid-related spending), but for most departments spending will remain below 2010/11 levels.

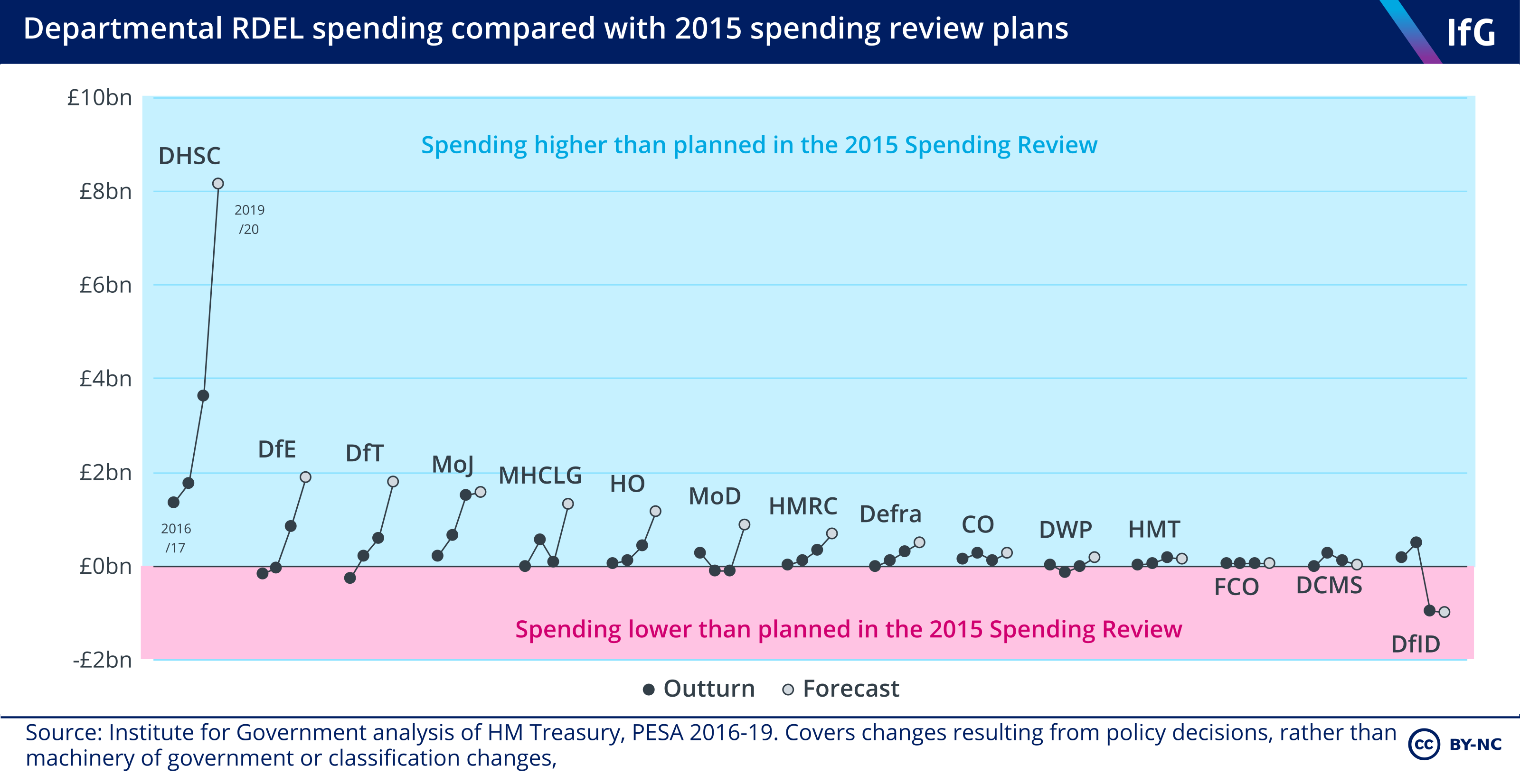

How does departments’ day-to-day spending compare to plans?

DEL budgets for each department are set at spending reviews, which set out government spending plans for a period of up to five years. These often happen after elections, but can also happen at other times when considered necessary by the government. The most recent spending review was in 2021, the first multi-year review in six years.

Between spending reviews, however, DEL budgets can change. Sometimes this is technical (e.g. reclassifications), but there can also be material changes, including:

- Policy changes such as the measures announced by the chancellor at the budget.

- Allocations from the reserve, which is a fund controlled by the Treasury that is used to top-up departmental budgets in the case of emergencies or unforeseen circumstances.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, the plans set out at the 2015 spending review had been all but abandoned. The government planned to continue to cut spending in most departments, but increased spending plans in response to public service pressures. The figure above shows planned spending in 2019/20, set out in Summer 2019 before the pandemic, was higher in most departments than originally planned. The increases were biggest for DHSC and DfE.

The government may also choose to use this flexibility to adjust spending plans set out in 2021. Inflation has been much higher than expected then, which means that plans that looked generous at the time no longer imply big real-terms increases in departmental spending.

How transparent are departments’ budget reporting?

Departmental spending figures and forecasts are included in several publications, including departmental annual reports, the Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses, and budget documents. However, it is surprisingly difficult to track changes, especially machinery of government and classification changes between publications. This is part of a broader problem with the transparency of annual reports and accounts, which vary greatly in quality and clarity.

The Institute for Government has long argued that departments should improve their annual reports and accounts – for example, by making them more easily understandable, allowing comparisons between years, publishing data in an open format, drawing a clearer link between spending and performance and including key data such as staff turnover. The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee (PACAC) has also called for improvements in its 2017 Accounting for Democracy and follow-up report.

This prompted the Treasury to convene an advisory group (including the Institute for Government, the independent fact-checking organisation Full Fact, and the House of Commons Scrutiny Unit) for a Government Financial Reporting Review (GFRR). 8 www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-government-financial-reporting-review

- Topic

- Public finances Civil service

- Publisher

- Institute for Government