Electric vehicle switch is a test of the government’s net zero approach

The government needs to tackle charging and equity issues to ensure a smooth transition to electric vehicles.

The government needs to tackle charging and equity issues to ensure a smooth transition to electric vehicles, argues Tom Sasse

At first glance the UK’s transition to electric vehicles looks like a policy success story. Electric vehicles (EVs) are increasingly visible on our streets; some 40% of drivers say their next car will be electric.[i] This shift is happening elsewhere, too, but the government can claim some credit for policies that have helped put the UK near the front of the pack: a 2030 target for ending the sale of petrol and diesel cars, a planned mandate on manufacturers to produce a certain amount of zero-emission cars (borrowed from a successful scheme in California) and subsidised EV purchases.

Lift the bonnet, though, and there are some problems. Charging infrastructure is not keeping pace with sales and, more worryingly, shows signs of being poorly thought through. And the benefits of EVs are overwhelmingly being enjoyed by the well-off, raising questions about fairness. How the government tackles these will be a test not just of its EV policy but its approach to net zero as a whole.

Electric vehicle sales are booming – but charging infrastructure is not

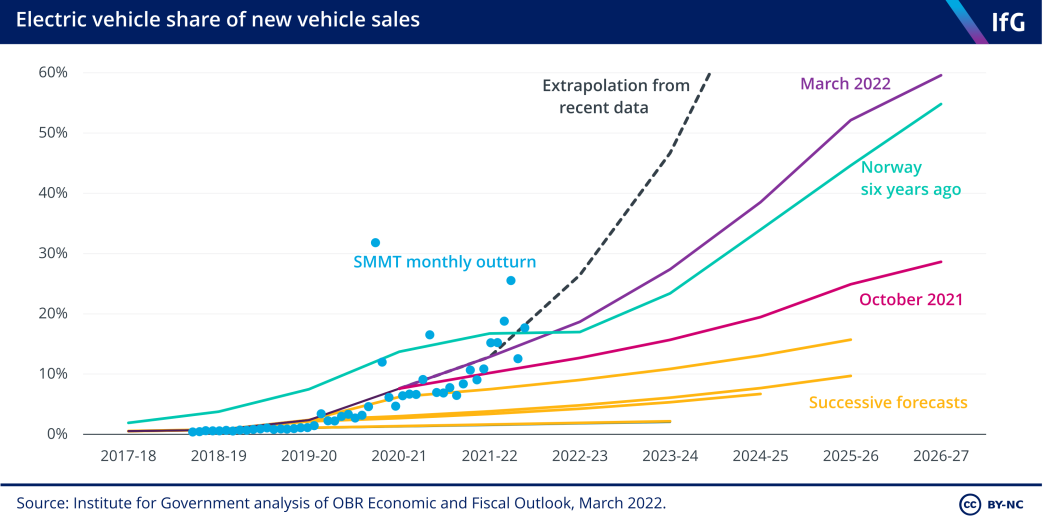

EVs accounted for 11.6% of cars sold in the UK in 2021, and over 15% in the first quarter of 2022. As the OBR has shown, the number of people switching has grown much faster than forecast – thanks in part to ‘push factors’ like high petrol prices and local low-emission zones. And while global supply chain problems are delaying some would-be switchers, that should be temporary, and on the recent trajectory it may only be a few years before EVs outstrip other vehicle sales.

However, the transition will only continue smoothly if the government addresses two big problems.

First, charging infrastructure is lagging behind sales and spread patchily across the country. In 2020 and 2021, the number of public charge points grew around half as quickly as that of EVs, and are often clustered in areas where charging providers can see a quick return on investment. As of March 2022, there was just one charge point for every 67 EVs in the North East, compared to one in nine in London. Around two thirds of drivers can charge their cars at home, but a lack of on-street charging and bottlenecks with motorway charging remain major barriers.

The government needs to work out how to remove planning barriers and finance charge points in areas of lower demand. The consumer experience – involving multiple apps, poor interoperability between chargers and opaque pricing – will need to be improved. And there is underlying work to do to ensure the electricity network can cope with demand, and that charge points can be easily and cheaply connected to the grid.

The current slowdown in sales provides an opportunity to address these issues. But while the Department for Transport’s recent EV infrastructure strategy contained welcome new targets and funding, it did not provide full assurance that the rollout will be well-planned and keep ahead of sales. Within industry there remain questions about whether the 2030 switchover date will be viable – and whether government has really gripped the delivery challenge and is co-ordinating adequately between local authorities, Ofgem and the distribution network.

The UK’s switch to electric vehicles is largely helping the well-off

The second issue is who is benefitting. The government has (rightly) framed net zero as necessary societal transition in which the costs and benefits will need to be spread fairly. But at the moment, the UK’s EV transition is not passing this test.

EVs are much cheaper to run than petrol and diesel cars – studies suggest by half to two thirds.[ii] This is due to extra efficiency, electricity being cheaper than fuel and the lack of tax on driving EVs (a road pricing system is likely, but some way off).

Yet amid of a cost of living crisis and record fuel prices, these savings are only available to those who can afford large upfront costs – and, of course, access charging. This means the market is dominated by fleet owners and, according to Auto Trader, those who are “significantly more affluent… and typically those located within the wealthiest postcodes”.[iii] Over a third of EVs are in London and the South-East, which does not suggest the transition is doing much to help levelling up.[iv]

The government may argue that its role is to boost the market, not manipulate it. But a focus on making EVs affordable across society – as New Zealand has done with its own net zero strategy, which includes retail policies aimed at low-income households and families – could further encourage uptake and so provide such a boost. Not doing so also carries risks: if manufacturers think EVs are out of reach for the UK mass market (or if they see export barriers to the much bigger EU market), they may choose to locate factories elsewhere.

The EV switch is a microcosm of net zero, with difficult questions about how to support low-carbon industries and technology adoption, co-ordinate complex delivery, and distribute costs and benefits. There remains a long way to go if the government is to make either a success.

[ii] Chris Goodall, What We Need to Do Know, 2021

[iii] https://www.smmt.co.uk/2022/03/uk-automotive-invests-10-8-billion-in-first-electric-decade/

[iv] SMMT

- Supporting document

- net-zero-agenda-2022.pdf (PDF, 290.61 KB)

- Topic

- Policy making Net zero

- Keywords

- Climate change Energy Environment

- Publisher

- Institute for Government