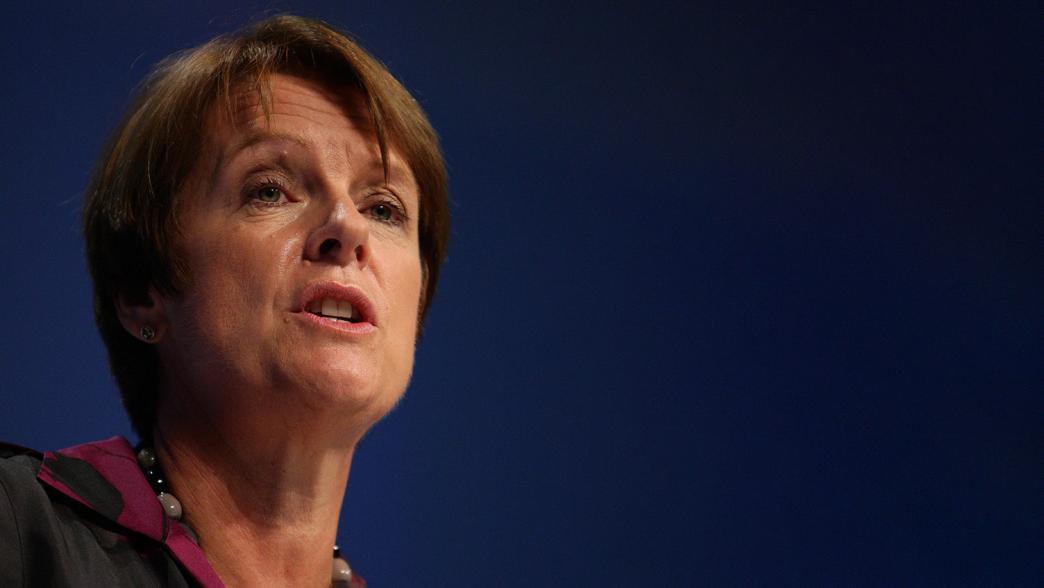

Caroline Spelman

Caroline Spelman reflects on her time in government for the Institute for Government’s Ministers Reflect project.

Dame Caroline Spelman was secretary of state for environment, food and rural affairs (2010–12). She was the Conservative MP for Meriden between 1997 and 2019.

Jen Gold (JG): Thinking back to when you first started as a minister, what was your experience of coming into government like?

Caroline Spelman (CS): It was like nothing I’d ever experienced before because I had not been a minister. And so I went from never having been a government minister to being in the top job, the Secretary of State, without having shadowed that department, other than briefly for three months, about seven years before. I was coming into government at a time of great difficulty, a time of austerity, to run a department, and to implement quite substantial reductions in our running costs in a department that I hadn’t studied. Although I did go to the Institute for Government [IfG] preparatory seminars, nothing really prepared me for that. If I’d gone in to run a department for which I had a business plan, such as the DCLG [Department for Communities and Local Government], and pretty clear idea of where I could begin to look for those savings, it would have been easier. But it was a tough call.

"I was coming into government at a time of great difficulty, a time of austerity, to run a department, and to implement quite substantial reductions in our running costs in a department that I hadn’t studied"

JG: And what kind of support was available? You mentioned the IfG seminars.

CS: That was about it, really. And it was semi-useful. I think that more does need to be done on big changes of government. I mean my party had been out of power for 13 years, so there weren’t a lot of people knocking around who’d had experience of being in government. If you hadn’t been a spad [special adviser], which is increasingly a sort of route into politics, it is a bit different. I had one junior minister who 20 years previously had been a minister, and he was delighted to find the Civil Service was as good as he remembered it 20 years previously, but that was about the extent of our ministerial knowledge.

JG: And what was the most surprising thing about your first weeks for you?

CS: Well it was just it felt totally and utterly unsustainable, and after about three months I just said to the diary secretary, ‘I cannot go on delivering at this pace, with no break between meetings to give me a chance on completely new subject areas which are very technical…’ It was exhausting. We had to come up with spending cuts of the order of 30% within five weeks of taking office. The civil servants were very co-operative, and they had already thought that whoever formed a government in 2010 was going to have to cut spending by 25-30%, that was perfectly clear. Whether it had been a Labour government or a Conservative government, we’d been one-third overspent for 10 years and they knew the order of the reduction necessary. But nonetheless the judgement about where to make the savings had to be made by the ministers, because we are the ones who have to go explain in the House of Commons why we are cutting in this area, not that area. So it really was tough. I wouldn’t want to go through that again.

"…the judgement about where to make the savings had to be made by the ministers, because we are the ones who have to go explain in the House of Commons why we are cutting in this area"

Nicola Hughes (NH): How did trying to get some breathing space in the diary go down? Did that work?

CS: Well a change of diary secretary helped. I think the thing that surprised civil servants is that we as ministers, particularly me with no ministerial experience, didn’t actually know what was required of us. So one of the things the Principal Private Secretary had to do in the early days and weeks was actually explain what we had to do, because no-one had explained that to us. And they were quite surprised that we didn’t know that.

NH: Based on your experience, how would you describe the main roles and duties of a minister?

CS: Well, the Secretary of State carries all the responsibility – it’s a ‘catch-all’ role. It is no good blaming other people for something that goes wrong. I know some people do do that, but it’s certainly not my style. And I think if you blame your junior ministers or you blame your civil servants in order to get yourself out of the firing line, that’s not a very honourable thing to do, and I think people will remember that. I come from the business world, and if I had gone down to the shop floor and blamed the workforce for the company not doing very well, I don’t suppose our productivity would have been brilliant.

"…if you blame your junior ministers or you blame your civil servants in order to get yourself out of the firing line, that’s not a very honourable thing to do"

So I think that the main thing is the Secretary of State has to set the direction and lead the department in the direction of travel – in our case that had been agreed by a coalition agreement. So we really started with a blank sheet of paper because I didn’t inherit a business plan for Defra [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs]. I had to take the coalition agreement and give interpretation to that in the form of a business plan for a five-year period in a very short order of time. That actually meant sitting down with civil servants and working out by what time they could deliver what. And I think actually on the whole, we did a pretty good job together as ministers and managers because we were only out by weeks on some of our delivery deadlines. And the one where we were out by six months was for a very good reason, and that was the badger cull. I demanded extra time to make that decision, which was the right thing to ask for, because a decision of that order where your life is at threat – I received death threats and so did my colleagues – and puts the department at risk, you’ve got to weigh that up very, very carefully.

So I think the Secretary of State takes overall responsibility, sets the direction, makes sure that what’s in the Government’s agreed programme of work is delivered to time, and then of course you have to deal with events, the unforeseen – in my case, the weather. I had absolutely everything on my watch as a secretary of state: flood; drought; food shortages; – and disease, be that TB in cattle or unforeseen chalara in ash trees.

"I had absolutely everything on my watch as a secretary of state: flood; drought; food shortages; – and disease"

JG: Is there anyone you saw as a good role model when you came into the position?

CS: Well, I have a mentor in Parliament who was a great help to me, Gillian Shephard, who’d been a government minister, and she’s been my mentor all the time I’ve been in politics which is 18 years. And sometimes when the pressure was immense and the decisions very difficult or I was taking the blame for something, I would go and talk to her about it. Gillian was a very good sounding board and she would agree that what I was being asked to do might seem unreasonable but I was going to have to do it. So actually having somebody who has been there and got the T-shirt is quite helpful.

I think amongst all the coalition ministers, a lot of us were rookie ministers. The Liberals hadn’t been in power since 1904 so the Liberal Democrat ministers were every bit as new as me, except they might have been on their briefs, they might have been on their subject areas.

So you were at an advantage if you had shadowed your brief for a long time and then went into government, because at least you had a technical knowledge. It did take me a while to work out the jargon at Defra, and the names of the organisations. I think it takes one calendar year to understand the cycle of the department, because I know in year two, when we got to some of these events, I would look out into the audience and think, I know you, I know your issues.

NH: Thinking about the day-to-day reality of being Secretary of State, how did you spend most of your time?

CS: A lot of face-time, not much downtime, and the only downtime you had was ‘red box time’, so it was kind of working time. I mean they are very, very long days, and I would get into the department easily by eight in the morning, sometimes earlier if there was a crisis, very early, and it would be face-to-face meetings all day long, wall-to-wall, until required in Parliament to vote. Then we’d switch to come over here where meetings might continue over here [in Parliament]. It was very difficult to arrange them here. The offices over here are very small and you couldn’t get the people in that you needed for briefings, and then the red box would arrive about eight o’clock at night but you couldn’t necessarily start work on it because you probably still had other meetings or events you had to speak at yourself. So you might start on the red box at 10 o’clock at night, taking two or three hours to do. I used to reckon I was doing really well if I got to bed by midnight, and quite often later.

It’s when you’re tired, that’s when I think red boxes are a bad idea. It suits the civil servants very well. They could do all their work during the daytime and then load up your box at night-time. And ministers are looking at stuff when they’re tired. I used to insist that longer documents went into the weekend box. Some ministers won’t have weekend boxes but I just found that I was just too tired to read a great thick document, a white paper draft for example – a very important document. You do not want to be reading that at 11 o’clock at night when you’re tired. You really don’t.

"It’s when you’re tired, that’s when I think red boxes are a bad idea. It suits the civil servants very well. They could do all their work during the daytime and then load up your box at night-time"

NH: So there’s an awful lot going on there, have you got any tips on how to manage all of this?

CS: Well, I’ll make you laugh. There was no work-life balance at all, and I have a family of three children and a constituency over two hours from London. In the week I found it difficult to cope without doing some exercise because I’m quite sporty and I’m used to doing exercise, and I found the amount of sitting and constant face-time very wearing. So I needed to do some exercise to try and stay fit. In the end I took to balancing my red ministerial folder on the handlebars of an exercise bike in the gym at seven o’clock in the morning, to the great amusement of everybody in the department [laughter]. But I was doing two things at once. I was exercising, and at my freshest part of the day, taking in the red folder of all the briefings on the day’s meetings. I found that the one thing I managed to do for balance.

NH: I think that’s the most innovative tip we’ve had so far!

CS: Well I’m not sure it was common practice by anybody else, but for me, personally, that helped. The other thing that I really fought the department hard on was not eating up all my constituency Fridays, because the public think that when you become a minister, you might neglect them. On one level constituents might accept that, but there have been terrible casualties in politics where people have gone into senior roles and then lost their seats because they became disconnected. So I insisted that we try to protect the Fridays. It didn’t always happen, but I kept up my schedule of surgeries in my constituency in order to stay connected.

I think that’s an important tip. You can loiter in London, if you’ve got a big majority, you could stick around in London. You could do all the media – that might well advance your career at one level. But the electorate may react to that by feeling that they’re not getting the service that they should, and I tried not to let that happen. I think the testament to that is my majority has gone up at every general election including the ones when I was a minister, so I think it’s important. And I also think it gets you out of the Westminster bubble and you feel much more the way the country’s thinking.

NH: So you mentioned a couple of events and crises, with Mother Nature hitting the department. Could you just talk us through an occasion where an unexpected event happened and how you dealt with that?

CS: So I had one real career-threatening disaster. I was on my way to negotiate the United Nations agreement in Japan on loss of species. I was at Heathrow, and it was a Sunday, and the Sunday Telegraph was on the table in the departure lounge where we were, and it said, ‘Government to privatise the forests’. And I said to my Principal Private Secretary, ‘What is that about?’ And he said, ‘I have no idea’. Neither of us had any idea what that was about. That is a scary moment and I had no choice but to board the plane and go to Japan.

I didn’t even realise at that moment that it was going to be so serious. Of course it blew up as a political campaign and it proved very difficult to wrestle it to the ground. Because something another department had done which was enter the Forestry Commission into a schedule of agencies to be reformed or repealed gave credence to the rumour that the Government was going to sell off the public forest estate. Even the Archbishop of Canterbury wrote to me and said, ‘Don’t sell off the public forest estate’. Of course I had to write back and say, ‘What is the basis of you believing this?’ But of course to people, perception is reality in politics, and the only way I could bring that crisis to an end was to take full responsibility for it. So I made the statement in the House of Commons in which I took responsibility for what had happened, because it was the only way I could draw a line under it and try and find a way forward. Indeed the Forestry Commission needed reform because it was losing a lot of taxpayers’ money in the way it runs its plantations, but I’d fought for its retention, that’s the irony of it, and that nearly cost me my job.

"perception is reality in politics, and the only way I could bring that crisis to an end was to take full responsibility for it"

NH: When you’re making big decisions like that, how do you go about it?

CS: Making the decision to do what, to retain it? I insisted with the Cabinet Office that we retain all the regulators in our department. You need regulators. The government can’t grow plantations of wood and control the market. It’s not ethical.

NH: No, I’m thinking more you’ve got to make a decision to do with, say, the Forestry Commission; did you gather people round a table, or…?

CS: So when I joined the department, we had 92 agencies. Over 90 – it’s quite amusing this – initially I was told we had 89 agencies, and I used that figure, and after a little while, the Permanent Secretary said, ‘Don’t use that figure, because we found a few more. You’d be better off saying “at least 90 agencies”’. And so the Government was trying to reduce the number of arms-lengths bodies by 50%. Well in the end I got it down to 36.

I applied some objective tests to the functioning of those agencies: were they essential to the running of the country? Did they perform a clear and distinct role? Were they duplicating the role of any other agency? Were they efficiently and competently run? So we applied these tests as a ministerial team to our family of arms-length agencies, and we retained 36, and that included all the regulators, because that’s the easiest case to ask for. You need to have regulators at arms-length from government. So this would include Ofwat [Water Services Regulation Authority], for example. So I fought to retain the Forestry Commission, and a lot of thanks I got for that, look what happened. Ouch!

That was a searing experience. And after that I think it shocked the department because I don’t think any of the civil servants saw the problem either, and they suggested to me that after that I should see everything that the junior ministers saw. Because otherwise you’re carrying total responsibility for your department, but you’re not actually seeing what somebody in a decision-making position is seeing, and they may not spot the pitfall, but you have to bear responsibility for it. That is known as a ‘one-two’ in the Civil Service. Hugely increases your workload, but, after my experience I would say as a Secretary of State, belt-and-braces, you can’t rely on a junior minister to spot the pitfall and you’re going to have to answer up for what goes wrong.

"…after my experience I would say as a Secretary of State, belt-and-braces, you can’t rely on a junior minister to spot the pitfall and you’re going to have to answer up for what goes wrong"

JG: And focusing on the positive aspects of your experience, what do you feel was your greatest achievement in office?

CS: Well I think the first natural environment white paper for 25 years was domestically one of our big achievements at Defra. I think personally bringing home two United Nations agreements, which I negotiated at a time when people were saying that, after Copenhagen and the failed climate change talks, they’ll never get another UN agreement. And I refused to believe that because I thought the loss of species was so important and so central that I could not believe that the countries could not be persuaded to do something about that.

But I had to work very hard at those United Nations agreements; I acted not just as a country representative but as a facilitator at the request of the Japanese between countries. So I brokered a deal between China and Brazil. And then subsequently at the Rio+20 conference, once again, a United Nations agreement, the British media dismissed Rio+20 as not likely to achieve anything. Actually, it did. 193 countries agreed to generate sustainable development goals [SDGs], and I personally worked really hard to achieve that because there was no kind of brand new idea, big idea for Rio+20, and we literally scoured the planet for who’d got the best idea. And it was really interesting that Colombia had come up with this idea about sustainable development goals and I backed them. I did a day-trip to Nairobi – there and back in a day – to go and support them in promoting to the United Nations Environmental Protection Agency, UNEP, that SDGs should be the number one objective of Rio+20. It gives me satisfaction to see it has happened.

"the first natural environment white paper for 25 years was domestically one of our big achievements at Defra"

JG: And if you were to identify key factors that were critical to that success, what would you say?

CS: So it’s being attuned to where is the best strategic thinking globally in your department area. How can you help incorporate the best and brightest new thinking in your subject area into your own domestic situation? And then how do you deliver on that to make the changes in law, or whatever it takes to make sure that the UK remains at the cutting edge?

NH: So what did you find most frustrating about being a minister?

CS: So slow! So you think you’ve decided something and you’ve pulled the lever, you’ve signed off the decision, and you discover three or four months later it still hasn’t happened.

NH: Why do you think that was?

CS: I think that the Civil Service is inherently cautious and so for something quite controversial, they might slow the process down – it is risk averse. But it is a bit frustrating when you think you’ve decided it and then you discover it hasn’t happened. That was frustrating. And interestingly enough, the civil servants who left the Civil Service and went to work in the private sector because there were few promotions – you know, it was a very difficult time, we were letting people go rather than taking people on and promoting them, so some of them left and went into the private sector – I got them back and I said, ‘Well, what did you discover? What surprised you?’ And they said, ‘The speed of decision making’. Okay, so definitely the speed of decision making is far too slow.

The other thing they said, which I think is interesting, is the willingness of business to undertake a U-turn when it’s not working, and I think by contrast with politics, politicians get beaten up for doing a U-turn when actually it makes perfect sense to do that. You know, here’s something that’s not working, let’s be honest, it’s not working. It’s costing the taxpayer a fortune, let’s face up to that and actually put ourselves on the right course. It’s remarkably difficult to do, but in business it’s much easier to do because they’re not going to waste the company’s money on something that’s not working.

"…politicians get beaten up for doing a U-turn when actually it makes perfect sense to do that"

NH: And did you work a lot with Number 10, other departments, the Treasury?

CS: Yes I worked a lot with other departments because Defra is a small department and the small departments need allies. It’s okay for the big departments because they can throw their weight around and get their own way, but the smaller departments have to work together. So I worked in alliance quite often with DECC [Department of Energy and Climate Change], which is Defra’s sister-department; we saw eye-to-eye on pretty much everything. DCLG quite often because we didn’t see eye-to-eye on everything, particularly not weekly bin collections, but we would see eye-to-eye over planning reform – that was my old brief. So when DCLG brought through their planning reform we went and supported them and I actually went to the launch and sat next to the minister. When we launched our white paper on natural environment, a DCLG minister came and sat with me at the launch to show our solidarity.

BIS [Department for Business, Innovation and Skills] was a good ally; it helped hugely that Vince Cable’s [then Business Secretary] wife was a farmer, he had a good innate understanding of agriculture, and also he recognised that Defra had in its family advanced manufacturing – the food industry. So DECC, Defra, DCLG, and BIS, and actually, sometimes DfID [Department for International Development] were good allies – DfID gave Defra money for forestry projects in developing countries because if you can stop people tearing down the timber and put them on a more sustainable footing by generating sustainable forests, you can create better livelihoods.

I found the Treasury very hard to deal with; it has all the power because it has all the money, and this was at a time when there was no money. The only thing that was a pleasant surprise – when Justine Greening was Economic Secretary to the Treasury, she was actually very helpful on the Treasury Green Book, which is where the Treasury looks at initiatives which are good for the economy and green.

The Cabinet Office was also powerful because they’re cross-cutting. I had enormous difficulty getting them to – well they never did really – hear the problems that the arms-length body bill was causing me. So those cross-cutting departments are very, very powerful.

It’s hard to get the attention of Number 10. We were on our own during the forests fiasco, and we were without a permanent secretary, a head of news, and a director of communications right throughout that period, which was really hard, especially for a brand new secretary of state a few months into the job. Key people can leave their jobs in the Civil Service, but it’s very slow to backfill. So it took us about eight months to get a new permanent secretary – well, at least six months, and that was very hard for a small department. Big departments could say, ‘Oh, we must have your Permanent Secretary because the security of the country is at stake’. So the smaller department has to deal with everything that’s being thrown at it, and that nature could throw at it without these key players. I think the Civil Service needs to look at that. In business that would not be allowed. In business you couldn’t have the chief executive go and have a six-month interregnum. I mean the stock price would go down.

"key people can leave their jobs in the Civil Service, but it’s very slow to backfill… it took us about eight months to get a new permanent secretary"

JG: So reforming the HR rules, is that what you are saying needs to happen?

CS: Yes, definitely. I think there’s very poor succession planning. So people in these key roles, you need to know if so-and-so’s rolled over by a bus tomorrow, who takes that job on? Not hold the vacancies open forever and ever whilst that individual is allowed to leave with no notice period, or a matter of days. It makes the department that loses the person in a key role very vulnerable.

NH: Based on your experience, how would you define an effective minister?

CS: Well, I would define it objectively as a minister who is good at delivering what they promised to do, and good at generating a good culture within the department in which the people who work in the department feel proud of what the department achieves and feel appreciated for what they do.

Now having said all that, that isn’t necessarily the currency in which politics operates. So if you can get good media headlines that is definitely one of the currencies that would be attributed to a good minister. But that’s okay if you have a department that can generate good headlines. I think that’s very hard at [the Department of] Health, I think that’s very hard at Defra because of the uncertainty of nature, and some other departments would find it harder to generate good headlines.

So objectively, to be a good operator you’ve got to try and do both things, I think.

NH: And you said how overwhelming it was for you coming into government for the first time, the new brief and all that sort of stuff. What kind of advice would you give to someone who was in your position?

CS: Well you can’t refuse it. Unless you’re feeling very bold, you can hardly refuse the opportunity to run a department you haven’t shadowed. But I would say that in the ministerial team, you probably want one minister who’s done that brief before. I was quite lucky because my minister of state had been in MAFF [Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food] 20 years previously. Some things never change and his sort of long knowledge of the subject area was a great advantage. And the other junior minister was a technical expert on agriculture and fish. If you’ve got a very technical brief and you’ve got a rookie secretary of state, I think you want some experience on the ministerial team, in a perfect world.

And you also want to leave people in post long enough to get on top of the brief and master it and do it well. And to be fair to David Cameron, usually he left people in post for quite long periods of time. Andrew Lansley [former Health Secretary] did six years, I think Eric [Pickles, former Communities and Local Government Secretary] did six years or so as well. I think that’s good and actually the stakeholders like that because they get to know the people involved. I think not changing the cast too frequently is actually quite a good call. I think he’s right to have taken that approach.

"I’ve got great respect for Defra. I think it has a very tough job as a department. And I’ve got high regard for civil servants who often get criticised"

NH: We’re running out of time now so we should probably let you go, but is there anything else that you wanted to raise?

CS: Well, I just wanted to say, even though I had a rough time, I enjoyed it. I look back fondly at some of the battles we fought at Defra. I’ve got great respect for Defra. I think it has a very tough job as a department. And I’ve got high regard for civil servants who often get criticised; they’re highly intelligent people and I think that we could do more to improve their lot. I think that seconding them out into the private sector or into the third sector and then back in with promotion to recognise what they had learnt outside the Civil Service would benefit the Civil Service. And I think generally better HR for civil servants would be a good thing.

- Topic

- Ministers Civil service

- Political party

- Conservative

- Position

- Secretary of state

- Administration

- Cameron-Clegg coalition government

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Legislature

- House of Commons

- Publisher

- Institute for Government