Select committees

Select committees are cross-party groups of MPs or Lords charged by parliament with a specific role or issue.

What are select committees?

Select committees are cross-party groups of MPs or Lords (or both) charged by parliament with a specific role or with investigating a specific issue. Select committees are one of parliament’s main tools for holding government to account.

Why does Parliament have select committees?

Select committees increase parliament’s capacity by allowing it to consider a wider range of issues or events at once. They can also allow MPs and peers to develop a degree of specialisation in a subject, encouraging deeper and more effective scrutiny of the government.

Most select committees are established under the standing orders – the parliamentary rules – making them permanent entities that exist from one parliament to the next (although their membership changes following an election). Other committees are appointed for a single session or to fulfil a specific purpose – such as the Commons European Statutory Instruments Committee – and cease to exist once the session or parliament is over or their work is complete.

What are the types of select committees?

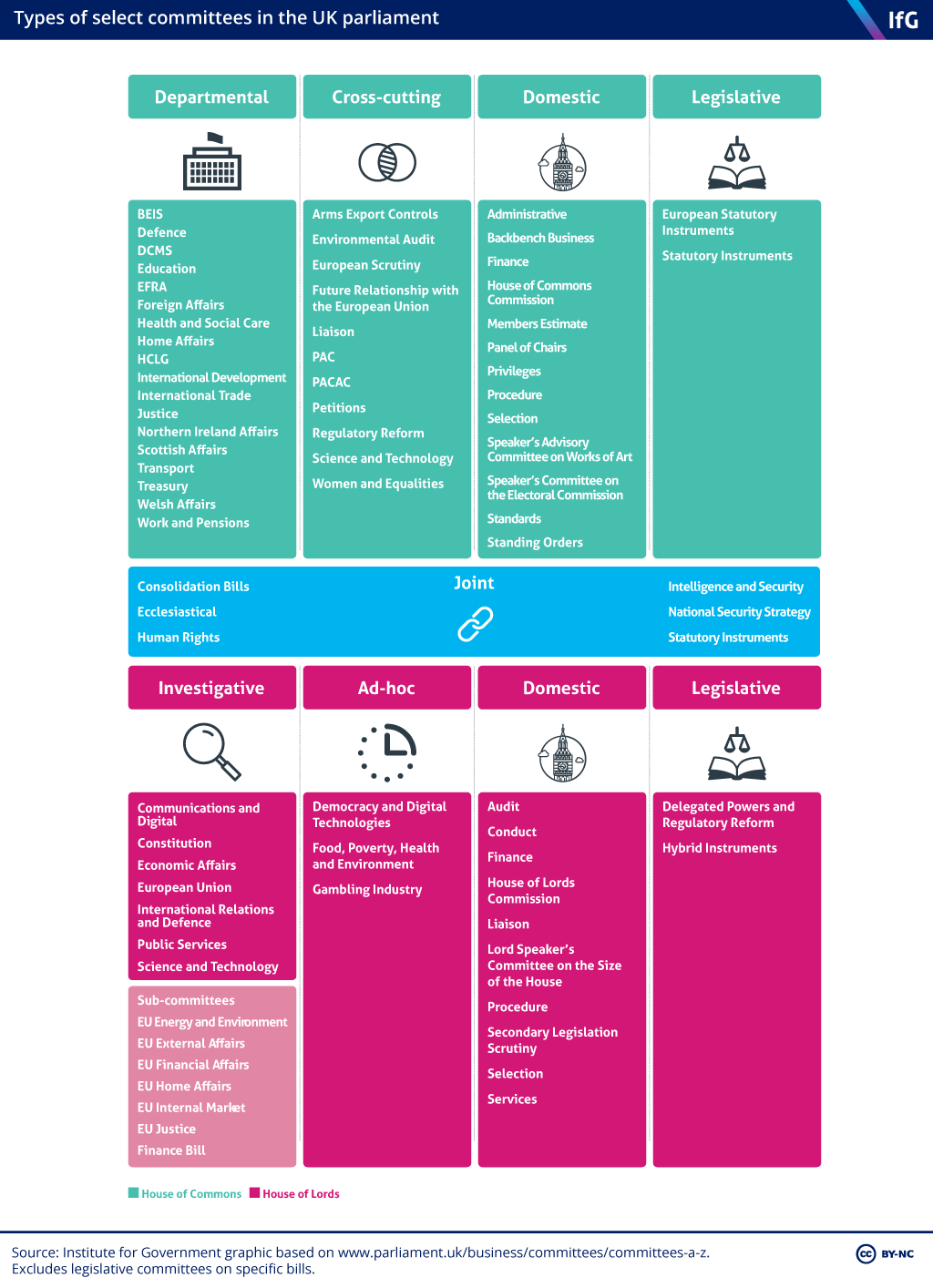

The Commons and the Lords committee systems are designed to complement each other. There is no single agreed way of classifying select committees. We have categorised them in the following way:

Select Committees in the House of Commons

- Departmental select committees examine the expenditure, administration and policy of a specific department and its associated public bodies (with some exceptions, for instance, the Treasury committee is responsible for both the Treasury and HMRC). They comprise almost half of the select committees in the Commons, although their precise number is responsive to organisational changes in government.

- Cross-Cutting select committees look across Whitehall to examine government performance on a single thematic issue. For instance, the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC) has a broad remit considering constitutional issues and the quality and standards of administration within the civil service.

- Domestic select committees facilitate some aspects of the parliamentary process or administration of the House of Commons, reflecting the fact the House governs its own proceedings. An example of a domestic committee is the Backbench Business Committee, which is responsible for organising the time set aside for backbench business in the Commons.

- Legislative select committees undertake takes in relation to the legislative process. This includes the Statutory Instrument Select Committee (SISC), which considers the technical quality of secondary legislation that is not subject to Lords proceedings.

Select Committees in the House of Lords

- Investigative committees (sometimes known as sessional committees) consider thematic issues and are renewed at the beginning of every session. Some of the investigative committees also form sub-committees to examine specific areas of policy.

- Ad hoc committees consider a specific issue for a single parliamentary session, or for around 12 months in a two-year session. Some ad hoc committees are tasked with conducting post-legislative scrutiny of a piece of legislation. These committees are normally dissolved once they have reported. Ad hoc committees help the Lords respond flexibly to topical issues, such as intergenerational fairness.

- Legislative committees undertake tasks relating to the legislative process. An example is the Delegated Legislation and Regulatory Reform Committee (DPRRC), which reports on whether the provisions of any bill inappropriately delegate legislative power, or whether they subject the exercise of legislative power to an inappropriate degree of parliamentary scrutiny.

- Domestic committees facilitate the processes and administration of the House. This includes the Committee on the Size of the House, which considers whether the size of the House of Lords can be reduced whilst ensuring it continues to fulfil its functions.

Joint select committees

In some areas, it is thought the effectiveness of parliament is improved by pooling the resources of both houses. One of the key ways this is achieved is through joint select committees, which draw their members from both the Commons and Lords. There are joint committees on policy issues such as human rights and national security, as well as practical matters affecting both houses, such as the restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster.

Who is eligible to sit on select committees?

Select committees are a key route through which parliament holds the government to account. To ensure their effectiveness, only backbenchers are entitled to sit on committees. Those on the government payroll are excluded. This includes government ministers, whips, parliamentary private secretaries, and government spokespeople in the Lords. However, former ministers can sit on select committees, and many chairs have government experience. This has raised questions about whether this provides a useful level of insight, or risks eroding the backbench nature of select committees.

What do select committees do?

To fulfil their aims, select committees undertake inquiries, publish reports, question government ministers and call for matters to be debated on the floor of one of the Houses of Parliament.

- Conduct inquiries: There is no formal template for inquiries. Some committees choose to hold many narrowly focused inquiries on specific issues, while others hold a smaller number of broad-based inquiries. Inquiries also vary in length, with some published at short notice in response to high profile events, while others are the culmination of several month’s work.

At the start of an inquiry, select committees usually publish terms of reference outlining its scope and purpose. This is often followed by an invitation to the public to submit written evidence. Stakeholders such as academics, think tanks, industry or lobby groups and interested individuals commonly respond and some may be invited to an oral evidence session. Witnesses will often provide written submissions to support their oral evidence.

- Publish reports: select committees may publish reports, often as the conclusion to an inquiry. These reports usually contain transcripts of oral evidence given to the committee, alongside extracts from written evidence, the committee’s assessment of the topic and recommendations to the government or other organisations, such as regulators.

Typically, committee chairs seek to ensure reports are unanimously endorsed by all members, as they are likely to be more effective in building cross-party support for its conclusions. However, select committees sometimes publish reports without the support of all members, such as when a committee has considered a controversial issue or where the conclusions are particularly critical of the government.

One unique aspect of select committee scrutiny is that governments are committed to reply to every select committee report within 60 days of publication (although often take longer), providing opportunity for dialogue between parliament and government over the direction and implementation of policy.

Select committee members may attempt to raise the profile of their reports by having them debated in parliament. In the Commons, reports may be the subject of a debate, or ‘tagged’ as relevant to a debate on a related topic.

- Ministerial appearances before select committees: departmental select committees routinely invite departmental ministers to answer questions on their areas of responsibility. This is an important, and visible, means through which select committees hold the government to account, particularly for its response to crisis or the delivery of government programmes. Ill-prepared (or advised) ministers can pay a heavy price for poor performance before a select committee. Indeed, Amber Rudd was forced to resign as Home Secretary after inadvertently misleading the Home Affairs Select Committee over the Windrush scandal in April 2018.

What powers do select committees have?

Select committees rely on powers delegated to them by their ‘parent’ House of Parliament, usually through the Standing Orders (the rules of parliament) or resolutions of one of the Houses.

While the exact powers delegated vary between select committees, they usually include the ability to:

- To send for persons, papers and records -This is the key evidence-gathering power and includes the power to call witnesses. However, it is subject to a significant limitation, namely that it cannot be used to compel MPs (with the exception of the Committee on Standards and Privileges), Lords, or the Crown (including government ministers) to attend.

- To report from time to time - including the power to report on matters beyond the immediate remit of the committee.

- To appoint specialist advisers – often academics in the committee’s field of interest.

- To meet away from Westminster – including the ability to travel abroad (usually subject to receiving the Liaison Committee’s permission).

- To meet when the House is adjourned, allowing select committee work to continue during parliamentary recesses.

- To appoint sub-committees, allowing select committees to build their capacity and introduce a further degree of specialisation.

- To exchange papers and/or meet concurrently with other select committees, allowing collaboration between committees and greater cross-cutting work.

In response to the Covid pandemic, many committees have also been permitted to meet remotely.

The most important power is to ‘send for persons, papers and record’. However, despite this seemingly broad delegated power, its practical operation is complicated by two factors:

- The strength of the power is undermined by the general acceptance that select committees lack a corresponding enforcement power.

- Select committees rarely rely on their formal powers in practice, meaning their strengths, and limitations, are seldom tested. Instead, select committees usually rely on good will, alongside political and reputational pressure, to compel witnesses to attend and request documents. However, formal summons are sometimes issued, with varying degrees of success.

These factors mean that if select committees’ informal methods of coercion prove ineffective, they are generally thought to lack any real ‘teeth’ to compel compliance. There is a risk that the legitimacy of select committees could be undermined if individuals are able to ignore them at will. This is particularly pressing given the increasing role select committees are playing in investigating wider societal and economic issues, which has seen them calling on witnesses perhaps less susceptible to political pressure.

Given these concerns, there have been calls to reform the powers of select committees, notably by introducing a specific criminal offence of contempt of parliament. This would allow procedural protections to be given to those accused of contempt. However, this would also involve a far greater role for the courts in policing parliamentary procedure. This has historically been avoided in order to preserve parliament’s control over its own affairs and parliamentary privilege, which provides parliamentarians with protection against civil or criminal liability for actions done or statements made in the course of their legislative duties.

- Publisher

- Institute for Government